No Worries

In recent years, I’ve become increasingly focused on landing projects on St. Thomas, St. John and a bunch of other paradisal surface eruptions off the east coast of North America: I like the people, enjoy the climate and truly love the laid-back island culture I find even among the high-end clients who call on me to design their poolscapes.

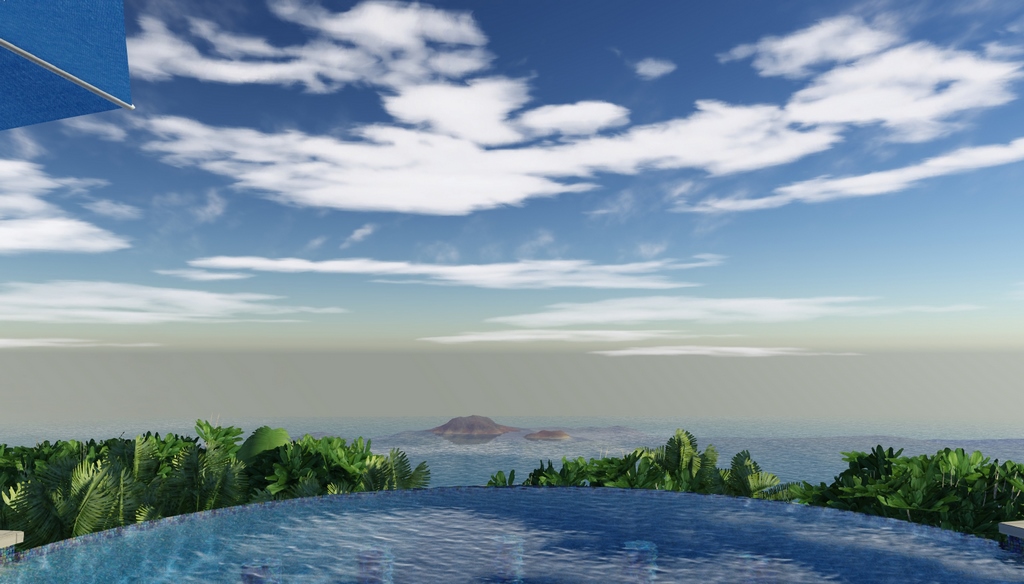

Quite often, the settings are the far side of spectacular, too, with views of multi-hued coastal waters of the Atlantic Ocean stretching out for miles, often interrupted by other islands that are just as inviting as the one I happen to be on. And my clients’ homes are frequently as dramatic as the settings, with an openness you just don’t encounter in other places as indoors and outdoors blend into amazingly seamless environments.

But while I’m absolutely smitten with these places, two important realities come to mind when I think about working across the water, particularly in relatively remote places: First, the sort of scheduling I do stateside is elusive if not laughable; second, the same goes for the very concept of deadlines.

That can make the work maddening at times, with the usual stateside sense of logistics and planning flying right out of the islands’ large, open windows. Still, there’s serious watershaping work to be done in these places – and I’m happy to oblige.

TAKING IT SLOW

In this case, I was referred for a project on St. John, one of the U.S. Virgin Islands, by Barefoot Design Group, a local architecture firm with which I’ve worked on several occasions. My initial role had to do with designing a community pool for a development of seven homes that were to be perched very near the top of the island’s highest peak – but that, as it turns out, was only the beginning.

The contractor was the owner of one of the seven units – a salesman with a genius for concept and detail but no relevant experience in construction or project management. He called my office and I was immediately intrigued because of the past positive experiences I’d had with other island projects. But it was clear that I had to go on site and size up my counterpart both as a prospective client and as a construction boss.

He agreed to fly me over, and I was a bit dismayed when I spent my first night in a run-down motel he’d arranged for me. But St. John is gorgeous, so I knew I’d enjoy the visit on other levels even if things didn’t work out as hoped.

As you might have guessed, our meeting on site went well – and I never stayed in that motel again. The project site overlooks Coral Bay on the eastern side of the island, and it’s about as pretty a place as I’ve ever been. The water is glorious, and the distant views include a number of other islands (including some of the British Virgin Islands).

The property itself is beyond impressive, perched on a steeply sloping hillside that cascades several hundred feet down to the water through scrubby clumps of native trees and brush. It was nosebleed territory up there, and at that point work had just started on terracing the rock face to accommodate the homes up above and the pool on a lower level.

| I knew from the moment I arrived on site that this project was about taking full advantage of the view from the pool terrace (top left). In subsequent computer-generated renderings, we pulled things together in a design that kept an eye on up-close details and greenery while stealing glances at Coral Bay and dots of land splashed across the distant vistas. |

The client and I formed an immediate bond, probably because we shared a sense of the wonder of the place. But it was clear that he had things to learn about contracting – and equally clear that I was going to get involved as much more than a one-off pool designer.

Once fully engaged, we moved through the design process pretty quickly, with me using the projected style and substance of the homes planned up above in my work down the slope. There was agreement among the partners that they wanted a lap pool, so it was going to be long and skinny. They also wanted a large deck area, an outdoor kitchen and dining area, a pool house, lounging areas, some in-pool seating and a vanishing edge lined with in-pool stools from which the precipitous views could be enjoyed to greatest advantage.

The homes were modern in style, so we kept the basic grid simple and linear – the exception being the semicircle we pushed out over the cliff: It broke the pattern, but it mirrored so many circular forms in the distant view that it was the right choice.

I knew going in that this curvilinear form was a violation of the basic rule that specialty construction on remote islands should stick to straight lines and right angles because you couldn’t count on crews to get things right. I’ve never believed that, and in fact I’ve found that there are untapped levels of competence in the framing trades in particular that made the semicircle just the right choice.

FILLING A NEED

Now let me tell you what it was like to work up above Coral Bay.

On one of my first visits after the plans were complete, the client and I realized we needed something from the local Home Depot – and I was elected. I drove my car halfway around the island to St. John’s ferry station, enjoyed the lovely ride to St. Thomas, drove some distance to the building center and was soon on my way back to Coral Bay.

Door to door, this trek occupied five full hours, so it was never one to be undertaken casually. But it made clear the point that purchasing had to be a meticulous, far-ahead process for every project phase and detail. And it made a disaster out of the common experience of opening a package and finding just a single bolt missing, as was the case with a suction cover that arrived one day, short that crucial part.

In that case, we ended up fabricating a steel bolt on site to allow us to complete water testing. When the missing stainless steel bolt arrived weeks later, we switched it out, happy about our ingenuity but confronted once again by how remote this place is.

| The twin storms that rocked St. John showed the integrity of the work that had been done by local tradespeople before the hurricane struck (top left and middle left): Their formwork was great, and the structures they set up came together beautifully (top middle right and right). But much of the work was harder than it would have been on the mainland, with finish material mixed with shovels in 55-gallon drums and applied without the aid of a tent in hot, humid conditions (bottom left and middle left). Gradually, everything on the terrace came together and was made ready for the trucks that delivered the water we needed to fill the pool. |

Concrete was another huge challenge. For hurricane resistance, just about every significant structure on the island is made from reinforced, poured-in-place concrete. (This, of course, explains why there are so many good framers on the island.) When it came time to place our first footings – all engineered in great detail by the staff at Barefoot Design Group – we contacted the nearest batch plant (on St. Thomas!) and ordered up a load packed up with retardants to enable it to survive not only the ferry ride, but also the long trip from the ferry terminal up to Coral Bay.

This ordeal – and its incredible cost – led me to make a modest suggestion: Why not rally the partners and set up a batch plant on St. John? It was a healthy investment in real estate, equipment, materials and personnel, but once it was up and running, it had every chance of becoming a true honey pot for its owners (and as it turns out, their first customer was the local government). In fact, the partners were in the black with their investment by the time our project was complete, and the island will benefit from their wise decision for decades to come.

So the engineering was sound, the forms were beautiful, the plumbing and steel went into place without incident and the concrete flowed freely: A perfect formula for good progress on the job site. Only two great challenges remained: Irma and Maria, back-to-back hurricanes that hit St. John like freight trains in 2017.

I was at home in Atlanta on both occasions, and I spent many nerve-wracking days wondering how to interpret the thin shreds of information I was able to glean about conditions on St. John. For Irma, it was four or five days before I heard from the client. For Maria, it was more than a week. The devastation was extreme, I learned, but the unfinished homes and the poolscape had come through relatively unscathed.

MOVING ALONG

I started this article with a meditation on Island Time, so let me begin winding it down by reporting that this project took three-and-a-half years from start to finish. Stateside, it might have taken a year, maybe a bit longer, but on St. John? Just about right.

What I discovered with this project in particular, however, is that lax attitudes about scheduling and deadlines didn’t necessarily apply when it came to doing good work. I’ve mentioned the great framing, but I also want to talk about the skill I witnessed in tile application with particular reference to the 38-foot long vanishing edge around the perimeter of the pool’s semicircular protrusion.

When we started on the edge, I told the application crew that the tile level had to be spot on – ideally to within a sixteenth of an inch if not better. There was some grumbling that they usually worked to an eighth or even a quarter, but what I discovered was that, when challenged to hit a higher level of precision, they were fully capable of hitting the mark – in this case to a point where the edge now fully floods with the flow from a garden hose.

It took time, but when the dynamics of the system were explained, they understood what was at stake, what was involved and how to meet the need. It particularly helped when I explained how the flow over the edge was meant to hug the wall on its way down, minimizing evaporation and saving precious water.

| From the home terrace above, the pool looks like an extension of Coral Bay – an effect that works even better down on the pool level, where views across the water and out to the bay are enchanting, especially at sunrise. (Photograph at middle right courtesy Steve Simonsen Photography, St. John, U.S. Virgin Islands) |

On that point, St. John is a place where electricity is expensive and water is ridiculously expensive. This is why we brought in solar paneling as well as a bank of storage batteries made by Tesla (Palo Alto, Calif.): These units capture and store enough energy that the development is almost always net-neutral with respect to the island’s power grid and has reached a place where the partners derive a bit of income by selling excess power back to the local utility.

We addressed the water issue with three 20,000-gallon collection tanks, all fed by rainwater. The first is part of the pool system and is therefore filtered and sanitized. The second is for irrigation of the extensive landscaping we planted. The third serves dual purposes: If needed for the pool, it is valved to add water to the system through the filter and sanitizing units. The rest is available for irrigation.

When it came time to fill the pool, the storage tanks weren’t fully charged, but we slowly filled the bottom two feet of the pool with some of the available supply before adding a torrent of purchased water, with the initial fill protecting the new plaster from the buffeting of gravity-fed water slamming through a two-inch line from tanker trucks parked about 50 feet above the pool deck..

All in all, it’s a stateside-quality, highly efficient, extremely satisfying watershape that just took its own time in heading for completion. And when you consider that there was a huge interruption in our progress as a result of the unprecedented one-two punch of Irma and Maria back in 2017, it really wasn’t as prolonged as it might seem.

I made about two-dozen trips to St. John in the course my consultations with the client, and I have to say I fell in love with the flip-flop lifestyle along the way. Now I know why people settle here, despite the challenges that Island Life – and Island Time – poses to mainlanders like me.

To see a brief video of the concrete transport on its way from St. Thomas to St. John, click here.

Shane LeBlanc has owned and operated Selective Designs, an Atlanta-based design/build firm specializing in custom pools, landscapes and gardens, since founding it in 2002. Building on a foundation of experience in landscape design, turf care, tree farming and nursery management, he has a degree in business administration and participates in the Genesis educational system. He may be reached at [email protected].