Helping Hands

The notion that water can be used to treat physical problems and conditions is not new. In fact, when you study the history of watershaping and aquatic design, one of the first things you learn is that the ancient Romans might actually have had a better grip on the healing and nurturing powers of water than we ever will.

The notion that water can be used to treat physical problems and conditions is not new. In fact, when you study the history of watershaping and aquatic design, one of the first things you learn is that the ancient Romans might actually have had a better grip on the healing and nurturing powers of water than we ever will.

In our own work in designing and installing environments that nurture the spirit and invigorate the body, we pursue that Roman heritage as best we can – and always keep water in mind as a key component.

The project described in this article stands as one our most dramatic explorations of the curative power of water to date. The pool, spa and surrounding facility were conceived to facilitate physical therapy for a young boy who had been partially paralyzed since birth. Our work with him, his therapists and his family ultimately taught us a great deal about the human body and the way it responds to exercise and movement in water.

More important still, this young man would truly capture our hearts with his winning smile, acute mind and unflagging spirit.

SPECIAL DELIVERY

In working with the boy and his family, we became intimately familiar with his physical condition. We were never told (and didn’t feel comfortable asking) about the cause. But it didn’t matter much anyway, because by the time we came to know him and his family, he was eight years old and everyone’s attention was trained on ways to help him in the here and now – and he was indeed making progress.

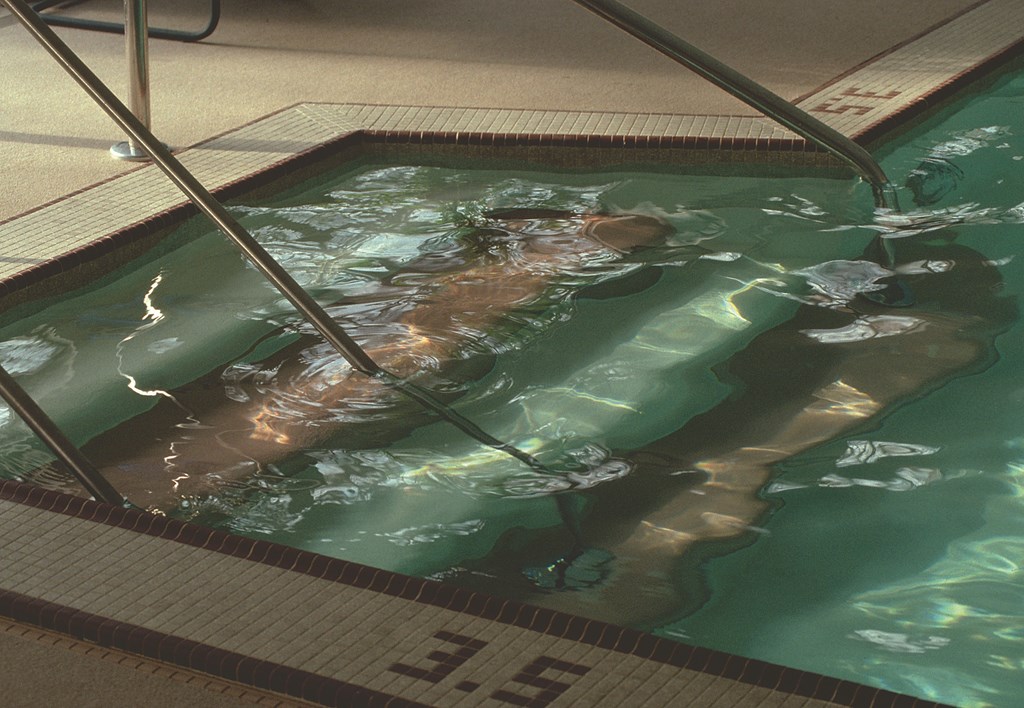

By the time we met him, in fact, he was somewhat able to maneuver on his own with a walker. This achievement was the result of long years in which therapists had been retraining and stimulating his neuromuscular system through intensive exercise of the muscles in warm water. The warmth of the water, hydrotherapy massage and muscle stimulation were intended to encourage the transfer of electrical signals in his neural pathways, with the hope that this would open up those pathways to a more normal routing and use of his body’s “control systems.”

At first, we thought this was only a hope or dream, but as we worked with the therapists, studied the young boy’s capabilities and observed the results, we began to understand the theories – and to believe wholeheartedly that his dream of gaining strength and mobility could one day become reality.

Our assignment and challenge was to design and construct a building that would house a pool and hydrotherapy environment along with a variety of special interior facilities that would accommodate the boy’s unique capabilities, requirements and potentials. It was also critical for the environment to be non-institutional, warm and nurturing – and to allow him to be as independent as possible.

From start to finish, details were to be dictated by careful observation of his physical actions and anticipation of his future development and needs. With a master’s degree in education and a particular focus on “special needs” children, Suzanne took the lead on this research from the outset. We also met frequently with his therapists and the boy either at his home or in a rented pool facility where he had originally started with the early stages of hydrotherapy.

WATCHING CAREFULLY

For a time, we simply watched as the therapists worked with the child and helped him perform mostly simple activities in and around the pool and deck. We took copious notes, recording the way he maneuvered in and out of the water, how far he could reach, what his limits were with respect to extending his arms and legs, and how he reacted to things that were happening to him in the water.

We posed many questions to his therapists, exploring a range of “what if” scenarios: What if, for example, he could grab something like the pool coping with his small hands, arms stretched out, and then push himself away from or pull himself toward the wall? What if all devices we made available were of push/pull rather than twist/turn configuration? And what if he accidentally fell into the pool? Would his coordination, strength and capabilities allow him to get out by himself?

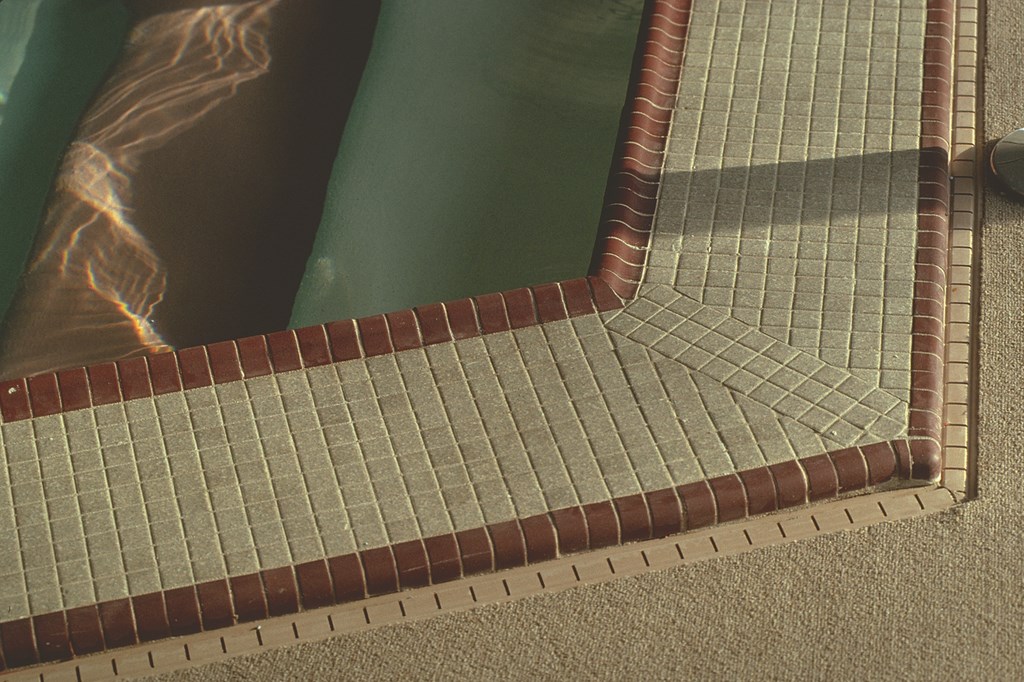

| Many of the pool’s details were dictated by the need to provide the child with things to grab, including coping specially contoured and textured to suit his small fingers and set up with a back edge that lets him pull himself out of the water at any point around the pool’s perimeter. Although the vessel has been set up with all the appropriate institutional fixtures, our design work put a premium on softening the edges and making the room seem more like a family den than a therapy suite. |

The answers to these and other questions allowed all of us, together as a team, to begin exploring a range of ideas, notions and possibilities that might help this boy. As we moved forward, we all recognized that this was truly an experiment that would unfold only with his participation as he developed and tried things out for himself.

The answers to these and other questions allowed all of us, together as a team, to begin exploring a range of ideas, notions and possibilities that might help this boy. As we moved forward, we all recognized that this was truly an experiment that would unfold only with his participation as he developed and tried things out for himself.

The therapists’ role was crucial in guiding our design efforts. They told us, for instance, that his body responded best to limited-duration water therapy at 92 to 93 degrees. Any cooler and his muscles would not respond very well; any warmer and he tended to fatigue easily and go limp. And although the dehumidification and HVAC systems were designed to achieve a year-round temperature of 75 degrees and 50% relative humidity when desired, the therapists tended to raise the air temperature to about 89 degrees when the boy was working with them in the pool area.

In other words, his basic needs dictated that the pool building and the hydrotherapy environment had to be designed and engineered with rigorous control of water, air, temperature and humidity. That last factor was particularly critical here in the Midwest, where dehumidification and control of condensation typically present unique sets of challenges.

As the period of observation went forward, we found that the child could float horizontally on his stomach in the water and could almost extend his arms straight out – but could not lift or raise them above his head. This extra range of motion was a critical therapeutic issue and among the skills his therapists were attempting to teach him.

A PLACE TO BE

To aid in this range-of-motion therapy, we designed a special nosing and coping detail that would give his small fingers something they could grip tightly as he floated in the water.

It’s a simple detail, but by enabling him to push himself away and then pull himself back, the nosing sets the stage for crucial progress in his therapy: As the therapists explained it, using the muscles in repeated forward/reverse motions would encourage the passage of electrical impulses from the brain to the central nervous system and, ultimately, to the muscles that were being instructed to perform repetitive actions or functions.

In the boy’s case, the therapists could use the nosing to begin a learning/retraining process in which they’d place his fingers on the coping and then push or pull him away, repetitively and mechanically. Their hope was that, by activating and physically manipulating the muscles, somehow this might activate or stimulate electrical signals and “open up” the boy’s own internal circuitry.

Early observation in the rented facility led everyone to believe that this approach was working. In fact, by the time we started construction on the pool and the surrounding structure, hydrotherapy was fast becoming the method of best resort when it came to helping him develop and expand his capabilities.

The coping detail was just one of many special features we set up for the pool. To help make him feel as though he was in on the fun when his family and friends were in the water, for instance, we created a six-inch safety ledge about 36 inches below the waterline around the full perimeter of the pool so that he could glide sideways around the pool edge while hanging onto the coping.

This lets him participate in games or simply relax with family and friends from anywhere along the pool’s edge – a small detail, but something that gives him extraordinary personal pleasure and satisfaction as well as a warm, secure sense of self-sufficiency. In addition, built-in grab troughs allow the boy to pull himself up and out of the pool anywhere around its perimeter.

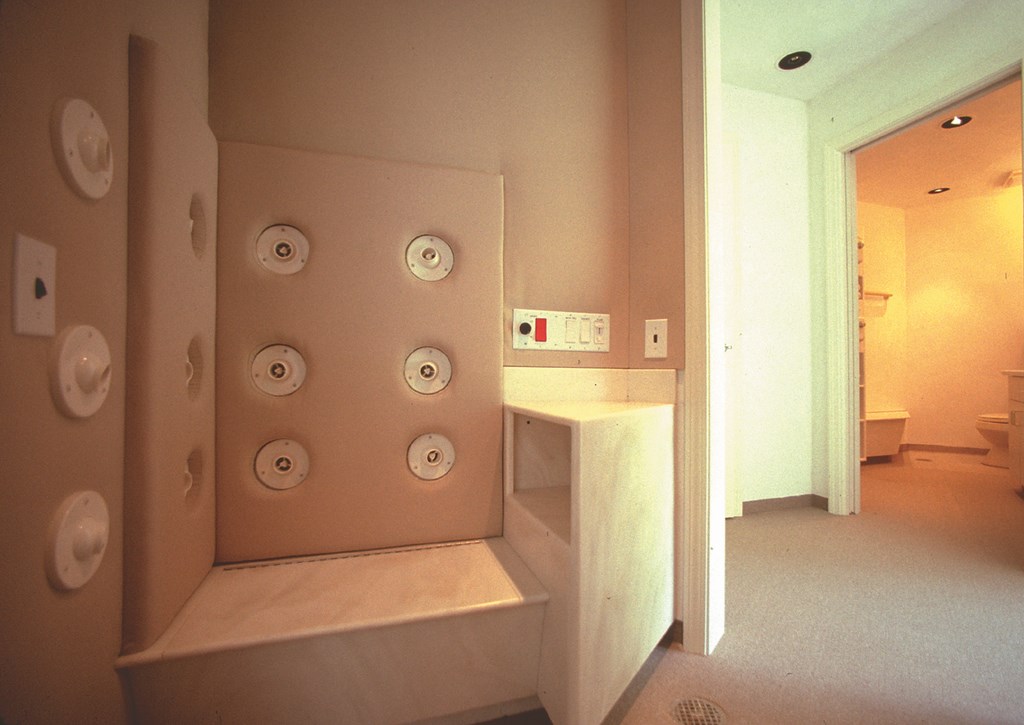

This same attention to detail extended beyond the pool to the sinks, toilets, benches and faucets – all mundane features that had to be reconsidered in terms of his capabilities and usage. (For more on the shower and dryer, see the sidebar above.) All controls for lights, automatic doors, dryers, showers and faucets were of a push type he could manage by himself.

PERSONAL FOCUS

From the start, the design intention was to make the pool environment a focal point where the boy’s parents and other siblings could all gather for games, picnics, parties and special events. So while we concentrated on getting the details right for the boy’s physical therapy, we were just as aware that pool games, kids’ stuff and family parties were on the agenda as well.

There’s nothing stark or institutional about the structure or the interior space. To be sure, all the necessary institutional-type fixtures are there, but we set up handrails, grab bars and balancing bars, for example, to look more like towel bars than institutional props, using a soft-beige plastic with a diameter small enough that the boy could use them easily with his small hands.

And the illusion is preserved by virtue of the fact that towels actually hang on some of the bars – a small touch, but one that adds considerable warmth to what could easily have become a clinical space.

To add these and other touches, we carefully watched as the child navigated in his walker and observed that it was quite a challenge for him to avoid tripping and falling or catching his toe or shoe on the smallest change in floor elevations. Door thresholds, moldings between carpet and tile and even flanges at floor grilles were tough to negotiate. To be sure, he was very careful and good at what he was doing, but he simply could not raise his feet up as he moved through a space. This is why we detailed all of the carpet, tile, floor grilles and trim to be exactly at the same level.

He had a terrific grip with his little hands and could push and pull quite well, but we also saw that turning or twisting anything was very difficult if not impossible. And while he could approach a doorway easily, it was hard for him to get out of the way to open a hinged or swinging door. So we set up his special space with motorized pocket doors activated by low-voltage touch plates set at his hand height on either side of the doorways.

All of the light switches are of a push/pull variety that is easy for him to operate, and they’re all ganged, engraved and color-coded so he can control the entire environment just as well as anyone else in his family.

COMPLETING THE SCENE

In many respects, the pool itself is ordinary – a simple, poured-in-place concrete rectangle with a cove for stairs. But that belies all of the care and consideration that went into setting up all the elements of this special space.

The coping/pool edge mentioned above, for example, was custom-made using one-by-one-inch ceramic tiles with a non-slip friction finish for safety and easy grabbing. The pool is also surrounded by a continuous slot drain set flush with a glue-down polyester carpet decking. An ozonator maintains and controls the water’s bacteriological characteristics – a special challenge in view of the 93-degree water temperature.

Large planter pockets were cut into the deck to lend a natural, open-air feel to the indoor space. The walls and ceilings were finished in a white, Portland cement sand finished plaster, while large, sliding-glass window walls open the entire space to the outside and to the beauty of the natural gardens beyond.

| Integrating indoors with outdoors – and thereby enhancing the boy’s sense of freedom and involvement with more than a universe confined by four walls – was a key part of the design program. The wall of windows lends a measure of openness to the setting year ’round, and we worked at making the spaces on both sides of the glass as warm and inviting as possible. |

The open shower alcove at one of the pool is finished with the same non-slip ceramic tile as the coping and features a little seat ledge. All of the special fittings, counters, ledges, hampers and seats in the changing room, body-drying alcove and toilet areas were fabricated from Corian with soft, large-radius corners and edges.

Low-voltage incandescent lighting was recessed all around the pool environment, and all of the fixtures run with slide dimmers that the boy, his family and friends can easily manipulate to set a variety of moods.

The Dry-o-tron dehumidification/heating/supplementary air conditioning system was designed to maintain indoor relative humidity at approximately 50% while allowing for temperatures ranging from about 75 degrees for parties and other gatherings to the 89 degrees the therapists wanted for the boy’s workouts. As was mentioned above, these control tasks, both warm and cool, are complicated by the fact that the water is maintained at an even 93 degrees.

The home itself is a two-story American Colonial with red brick, white trim and a gable roof – all simple and ordinary, but with some nice woodwork in the family living and dining rooms and generally of sound design and construction. Before we attached the pool building to the rear of the house, the landscape consisted of a large, flat lawn.

We focused some of our attention on making the exterior space more attractive, adding a series of intimate little gardens, terraces and walkways set among large, densely planted evergreen trees we used to establish a sense of privacy. The trees were set in long, undulating beds of evergreen ground covers, with colorful seasonal flowers along the borders.

To make it seem as though the new garden spaces and the pool structure had always been there, we planted groups of mature flowering shrubs and placed specimen plants of climbing evergreen vines on the new brick walls.

A FINE FINISH

There’s a bittersweetness to this story because, obviously, there may be no “cure” for the boy’s condition, and any progress that may come through treatment will always be incremental and is often very subtle. But once his pool was in and he’d had the opportunity to experiment with his exercise regimen for some time, one and all were happy to see that he had already developed enough strength to pull himself out of the water and onto the pool deck all by himself. He had never been able to do that before.

It has been some years since this project was completed, and we do not know if this facility was ever made available to others with similar challenges. But we do know that much of the research and the knowledge we and the therapists gathered by experimenting with a variety of physical therapies has been shared with other professionals and institutions that deal with patients with these challenges.

In our own way, we are proud to have been able to help.

Ron Dirsmith is principal architect and cofounder of The Dirsmith Group, an architecture firm based in Highland Park, Ill.,with operations worldwide. He and wife Suzanne established the firm in 1971 following employment with the prestigious firms Perkins and Will and Ed Dart Inc. He has a BS in Architectural Engineering and a Masters in Architecture and Design from the University of Illinois. He is also a Fellow in Architecture of the American Academy in Rome, which for more than 100 years has been a research and study center for America’s most promising artists and scholars. Dirsmith is one of only 172 architects to have been granted this honor. Suzanne Roe Dirsmith, president of the firm, holds a BS in Education from the University of Illinois and a Masters in Education from National-Louis University. She heads the education division of The Dirsmith Group, an effort dedicated to forwarding design and architecture education within the architectural community and to fostering new thinking and raising awareness of architecture and landscape design as a blended whole.