Natural Transitions

Finding ways to blend the angular rhythms of modern architecture with the sweeping splendors of nature constitutes one of the more difficult challenges faced by today’s watershapers.

In the case of the project pictured on these pages, we were contacted in 2002 about an enormous, modern-style home on Mercer Island overlooking the shore of Lake Washington, right near Seattle. The property was being remodeled, and the owners wanted a set of watershapes that would enhance the beauty of the two-acre estate while more convincingly integrating the geometry of the structure with its woodsy lakefront setting.

The solution: a set of watershapes that start near the house with perfect geometric forms that stick to the architect’s original design, then moves down the hillside through various transitional stages to a pond feature that looks like part of the natural landscape.

COMING TOGETHER

Philosophically, we were all quickly on the same page, but as we began approaching the work and the job site, we recognized a couple of problems.

First, there was no real access by road, a major issue given the heavy equipment and large amounts of material we needed to bring on site to get the job done. Before long, the island setting suggested the solution: We loaded everything onto a 50-foot barge and transported by water to the shore at the foot of the job site.

|

Getting Things Done As mentioned in the accompanying text, access and the weather were big factors in how we approached the tasks at hand on this hillside project – and both put a premium on coordination and teamwork. I worked side by side with the landscape architect Bruce Hinkley in planning and installing all systems needed to whip the slope into shape. We established the plumbing runs and grade transitions between the slope area and the new stream and managed transitions in ways that looked natural. To a large extent, that meant fashioning rock formations that worked visually with the retaining walls at the top of the feature. Typically, with boulders of the size and quantity we used on this project, we’d crane material into place. But we couldn’t bring a crane on site, so we ended up shuttling rock up the slope using a track hoe after we’d lined the space with an EPDM liner and laid down a layer of concrete. We would then track our way back down the hill, placing rocks on top of the lined concrete and essentially creating a rock wall that transitioned into the pond area. When we reached the bottom of one stripe, we’d move laterally to the next area and restart the process up on top. The pond area at the base of the falls was flat. All we did was excavate it, lay down the liner and flash on a coat of gunite before moving across the hill, stripe after stripe. — C.V. |

Second, there was the weather. Much of our work was planned for execution during the Seattle area’s long rainy season, which led to difficult scheduling and steady coordinating with a general contractor who was working very hard to keep the project on track and on time.

Logistics aside, we were challenged more profoundly by the fact that the client and renovation team were looking for something truly spectacular in our work to replace an existing waterfeature on the slope leading to the lake – a waterfeature that everyone agreed had been an eyesore in concrete and rock.

We had our marching orders, and it was time to get started. We began by demolishing the old waterfeature, carting away everything but a handful of nice-looking boulders we decided to keep and setting up the blank canvas onto which we were to paint a careful composition of multiple features in vastly different styles.

As seen in the accompanying images, the appearance of these watershapes couldn’t be more varied from top to bottom. But amazingly, when you move from one space to the next in a progression either up or down the slope, there’s a certain logic to the experience that makes everything seem to fit.

One more challenge to mention: For the most part, our work at Land Expressions is purely naturalistic. Projects such as this one teach us that those sensibilities can exist in harmony with the more precisely controlled aesthetics of geometric architecture – an exciting lesson to learn.

Up on Top

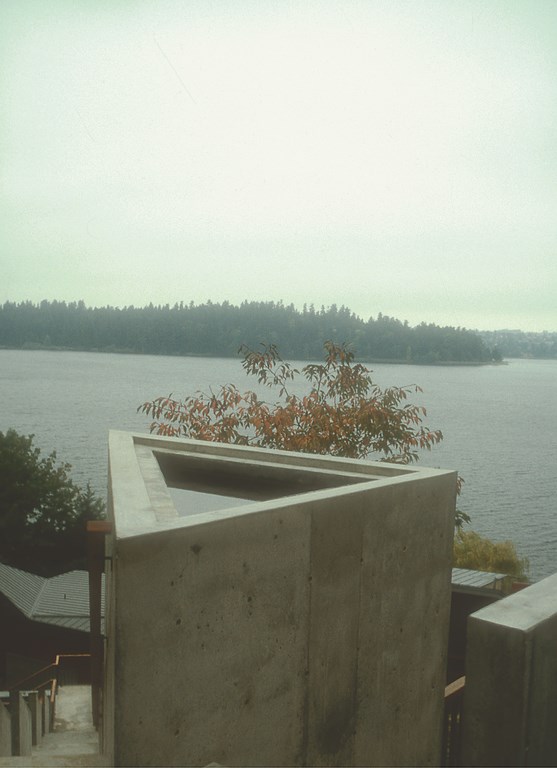

The hillside offered us dramatic vertical transitions and a clear path to follow with respect to the visual movement of the watershapes, but it all starts with a topmost reflecting pool that is modern, geometric and static.

This six-foot equilateral triangle of highly reflective water rises on a dramatic concrete turret set adjacent to a deck and a long set of stairs that leads to the lower sections of the site. The triangle contrasts with (but leads the eye to) distant views while fitting perfectly within the context of the home’s architecture and beginning the process of integration by engaging the observer with views the lake beyond.

The walls for this watershape had been poured by the general contractor before we came aboard with the project and were six inches thick. Had we been on hand, we would have directed the contractor to pour the walls at four inches to accommodate the thickness of our liner-and-concrete finish. As it turns out, we created a step detail to maintain the aesthetics of the six-inch wall – and in so doing added a detail that accentuates the triangular form.

Pouring Down

We set up the triangular turret with a 40-mil PVC liner using a special gasket-and-track assembly with a neoprene seal before applying gunite and troweling the material to a smooth finish. The vessel itself is about six feet deep, but the majority of that space is filled with a dark basalt riprap the raises the visual bottom of the pool to a mere 12 inches.

An overflow line runs from the water level to a point about halfway down the height of the feature and a penetration on the outside of the turret. This line sends a small flow of water into a diminutive catch basin at the foot of the structure.

Limestone decking is cantilevered over the edge of the catch basin, which is filled with the same basalt riprap as the reflecting pool. A small pump set beneath the layer of rock collects the water and sends it back to the top of the structure. The waterfeature operates independently with respect to water circulation, but it is tied visually to downstream features by way of a dry streambed that runs toward another architectural watershape in the courtyard adjacent to the home’s front door.

Architectural Drama

The dry streambed terminates at the top of a 12-foot retaining wall. Just below that point on the other side of the wall, a scupper spills water into what became known as the courtyard feature.

Also in the shape of a triangle, the small catch basin complements and contrasts the upper feature in that it is recessed beneath cantilevered stone decking and nestled against the foot of the retaining wall. A shallow, eight-inch-wide runnel filled with dark riprap stones extends from the shallow pond and appears to flow beneath set of steps next to the front door. (Again, the scupper and catch basin operate as an isolated system.)

The Key Transition

The runnel leads the viewer’s eye to a patio adjacent to the front door that surrounds a small, rectangular pond perched atop another tall retaining wall. The decking material cantilevers over the water, in which large pieces of cut basalt create a dramatic scupper that spills over an 18-inch weir at a rate of about 50 gallons per minute.

As with the uppermost triangle feature, the geometric waterfeature leads the viewer’s eyes toward Lake Washington and the forests that hug its shores.

The architect and homeowner were keenly interested in maintaining a minimum amount of freeboard between the pond’s water level and that of the decking. By calculating the desired flow over the weir and using valves to adjust the return flow into the feature, we were able to create what is very close to a knife-edge waterline at deck level.

Shifting into Natural

From the weir on down, the tone of the watershape shifts significantly as the water flows into the headwaters area of a stream, waterfall and pond system that leads to the lakeshore.

The waterfront is about 150 feet across, and the house sits upslope from the water by about 40 yards. Within this space, we created a watershape system that is tied visually to the architectural watershapes above by scupper effect at the weir and the dominant use of basalt rock.

But as the observer moves down a set of steps to this lower level, modernity and hard angles are left behind, replaced by a separate environment of vigorous, moving water, lush plantings and bold, rugged stones. It’s the perfect transition to the lake itself – the site’s ultimate watershape.

Water flows at only 50 gpm across the basalt weir, and a discharge pipe located beneath that cascade supplements the flow to about 350 gpm. The stream flows through an area of thick vegetation (highlighted by a beautiful red maple specimen) and over a set of small falls on its way to the main cascade, which drops 15 feet to a level area before flowing beneath a 12-foot wooden bridge.

Down to the Lake

From the calm area beneath the bridge, the stream continues down another set of small cascades into a 25-by-15-foot pond in which the flow terminates about six feet above the water level of the lake.

We used a 40-mil PVC liner in the pond and worked very hard to leave no liner or concrete exposed to inquisitive eyes. The boulders are set on concrete and have been back-mortared into place. We also went to great lengths to backfill spaces behind and around the rocks with soil suitable for plantings, especially on the hillside transitions where we wanted to establish key pockets of greenery.

The wooden bridge is part of a path that traverses the rocky slope above the shore. The path provides access to multiple deck and seating areas that bring the observer into close proximity with the cascading water.

Clayton M.Varick is a project manager with Land Expressions LLC, a landscape architecture and construction firm based in Mead, Wash. A graduate of Washington State University, Varick grew up in the landscape business and worked for his father’s firm, S. Varick Landscaping, in Seattle. That experience, coupled with his bachelor of science degree in Landscape Architecture, has enabled him to progress quickly at Land Expressions. At 27, he is manager of the company’s Water Division, where attention to detail and dedication to the work have made him a valuable member of the company team.