Thoroughly Modern

I followed a well-worn path when I started designing watershapes: I acquired a drafting table and worked at gaining proficiency in the use of pencils, protractors, scales, squares, various templates, colored markers and a multiplicity of other drawing tools as a means of communicating design ideas to my clients.

To this day, I have great admiration for those who work quickly and decisively with these tools, but about ten years ago I was introduced to an array of digital design systems – and I’ve been moving in their direction ever since.

Even a decade ago, the new software systems that were emerging were, to me at any rate, completely mind-blowing. When I first saw one demonstrated at a trade show, however, I soon recognized that learning my way around these systems wasn’t going to be easy. Nonetheless, I picked up some demo disks, took them home for review and soon decided to sign up for a bit of training.

That was in 2005, and I look back on it as a major shift in my design career – that is, the point where I started migrating from manual to digital drawing. It’s a transition that many watershapers have gone through, and this is the first in a series of articles will give several of us the chance to tell our stories of what it took to move us forward with this new technology.

SMALL STEPS

The truth about my design work before I pursued the digital alternative was that it was never simple. I would work away at basic plans and knew that any changes I might want to make would be time-consuming and sometimes difficult. I also knew that there were more steps in the process: Once my work was effectively complete, I’d hand my drawings off to our landscape designer for planting details – and then everything was handed over yet again for conversion to a computer-assisted design (CAD) system for our final client presentations.

The process we followed was highly refined and accurate, but changes were always a killer. We knew well enough to build time into our schedules to accommodate what could become complex processes of give and take, but we also knew we could easily be thrown off course and left to scramble toward the finish line.

And I wasn’t sold on the digital approach right away. In fact, one of my first thoughts was that it would make more sense to improve my drawing skills instead, so I signed up for a Genesis 3 perspective-drawing course with David Tisherman and spent some time upping my own game to make life easier. As I noted above, I have nothing but admiration for those who draw quickly and accurately, and I was amazed by what Tisherman managed to convey in his classroom.

| At left is a hand-drawn, marker-colored design I prepared in about 2005, before I had my first encounters with computer-driven design systems. At right is the completed project, which shows what we were able to achieve using ink and paper. When I look back, however, I have to wonder how these clients were persuaded by what I now consider to be a very modest presentation. |

But I found through this experience that, given my skill level with pencils and paper, the three-dimensional design programs I’d tried would let me do everything I most needed to do; moreover, I could do it faster, with perfect perspective and scale. And once I started doing presentations with digital artwork – something few others in my area were doing back then – I couldn’t help noticing that my clients were amazed by the technology. (And they still are today.)

As I explored the possibilities, I tried AutoCAD (from AutoDesk, San Rafael, Calif.) and a system from Dynascape (Burlington, Ontario, Canada). Both were excellent, but they weren’t geared toward watershape design. That’s when I came across Pool Studio (from Structure Studios, Henderson, Nev.) and was impressed from the very start.

GATHERING STEAM

Back in those days, Pool Studio was more difficult to learn than it is now. The system was less intuitive, and online learning aids were not as widely available. As a result, the transition from hand- to digital drawing wasn’t anything that happened quickly in my shop.

At first, in fact, I mostly used the program to introduce concepts to clients in three dimensions – a much quicker process on a computer than at a drafting table, at least for me. All through this time, our design process was still mostly manual, with final hand drawings still being converted to AutoCAD.

Basically, we kept our feet in both worlds because I was neither confident nor proficient enough to show our clients live versions of their designs on our system; even more so, I was far from ready to be revising and editing jobs with clients looking over my shoulder. But practice makes perfect, and before long my skills caught up with my needs and I found myself participating in an all-digital workplace.

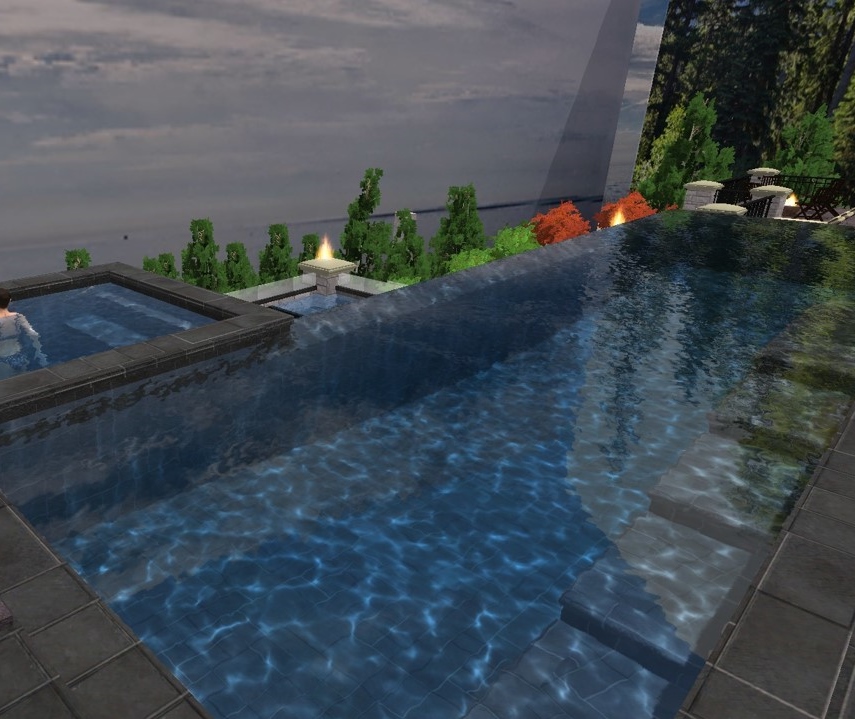

| This huge project was managed entirely through use of our 3-D design system. At left and middle left are early digital drawings of the hilltop pool seen at deck level and in a bird’s-eye view. Taking those images through to completion involved us in blasting through tons of rock and pouring more than 1,100 cubic yards of concrete (middle right and right). The pool is suspended above and cantilevered over a mechanical room and a large pool house. Access to those areas from the pool deck (bottom left) is via the leaded-copper pergola seen in the lower right corner of the photograph at bottom right. By the time we were done, the home had a pool, a spa, an elevated sports court and large, multi-tiered decks. |

The seductive thing about the technology is the fact that it makes the process of changing drawings so much simpler and faster. Where in the past I’d sometimes find myself compromising to avoid the necessity of making big changes, that stopped being any kind of factor in our digital workstream. And I must say it’s nice to leave behind that nagging sense that I could do better. In fact, as I became confident with my new skills, I also found that my designs were becoming more and more complex.

Gradually, I gained the confidence I needed to work without a net and went live with my clients. With just that step, I’ve done more to get them truly engaged in the design process than I would ever have thought possible. They’re actually excited about being involved, and it’s relieved the process of any sense that I’m telling them what they’re going to get.

|

A Critical Eye Often, clients will come to me with a design already in hand. On some occasions, these documents have been prepared by an architect or some other designer who has only limited knowledge of pool design and construction. This frequently leads to “issues” with the design, typically with lines of sight related to vanishing-edge pools, for example, or with myriad details related to safety. Typically, the interiors of these pools are blank: no steps, no benches, no shallow lounging areas – and no lights, umbrella holders, depths, transitions, surge tanks or edge details. And then there’s the fact that only rarely is enough space allocated for equipment rooms – a real problem with complex watershapes and a serious problem with indoor ones. Interestingly, we’ll also frequently encounter the very common problem of “perfect CAD.” This happens because there is a tendency for people in various disciplines to assume that, because CAD drawings look so professional and organized, they must also be correct – and in some cases nothing could be farther from the truth. The flaws we find in this design work are easily called out when we convert the drawings to 3-D: We now have a tool that helps clients and even the designers they’ve hired understand what’s going on – and see the need to make adjustments that will ensure a project’s success. — B.J. |

It truly is remarkable: Changes to designs are instantly shown in three dimensions in perfect perspective, with viewpoints from any location shown accurately. It’s always been true that clients will acquire first what they can visualize best; what’s new here is the sense they get that they helped create what they’re seeing on the screen. That’s powerful stuff.

HOOKED

When I started pursuing this technology, I was mainly thinking about my clients. As I became more deeply involved, I soon discovered that the digital drawings in both two- and three-dimensional versions were also proving invaluable in clarifying my conversations with construction crews and the various subcontractors who participate in our projects.

I guess it had never occurred to me that the people who were building my designs had every bit as much need to visualize the final product as my clients did – and the same is true of the engineering firms that consult with us. Again, these communications have become easier, faster and more detailed as my own facility with the software has grown.

I was recently asked, “If you had to do it all over again, would you have followed the same path?” My answer is a resounding “no,” and for a simple reason: If I had to do it all over again, I would’ve gotten myself started with digital design years before I did!

Barry Justus is president of Poolscape, the international-award-winning design/build firm he founded in Toronto, Ontario, Canada, in 1991, and principal at Justus International Consulting. A graduate of the University of Western Ontario, he has written more than 40 articles on pool design and construction for a variety of magazines. He is also an instructor for Genesis 3 and is a member of the Society of Watershape Designers. He may be reached at [email protected].