Material Issues

It’s a little too easy to lose sight of what holds the most meaning our work as watershapers – even when it’s out there in plain view.

In fact, if we’re to be honest in assessing the palette of finish materials we use, I think most of us would have to concede that these products can become so familiar that thinking creatively about the full spectrum of their possibilities is something that often falls by the wayside.

I believe we should be on guard against that sort of complacency, because when we do push beyond the limits of familiar options and the choices offered by our most convenient suppliers, we almost invariably find we have the ability to carve new creative pathways for ourselves and for our clients.

And when that journey is guided by a search for visual and spiritual harmony – instead of simply by what’s available in the product catalogs we have most readily at hand – a greater potential for exciting and delightful results awaits us. After all, when you’re thinking about finish materials, you’re considering nothing less than the visual essence of the experience you seek to create.

In this series of articles, we’ll take a look at materials we all can use to set ourselves apart from the templates, familiar patterns and artless repetition that surrounds us on all sides. And nowhere is this broad set of possibilities more evident than when we consider the rich traditions and spectacular beauty waiting for us in the realm of tile.

TILE BY DESIGN

Tile is particularly important to watershapers because it is the single construction material most closely associated with water.

From Roman baths and Moorish fountains to modern-day pools, spas and fountains, wherever you see water in the human environment, you almost always see tile as well. And because so many people are instinctively attracted to water, the tile we use in conjunction with it carries an unusually high degree of visual significance.

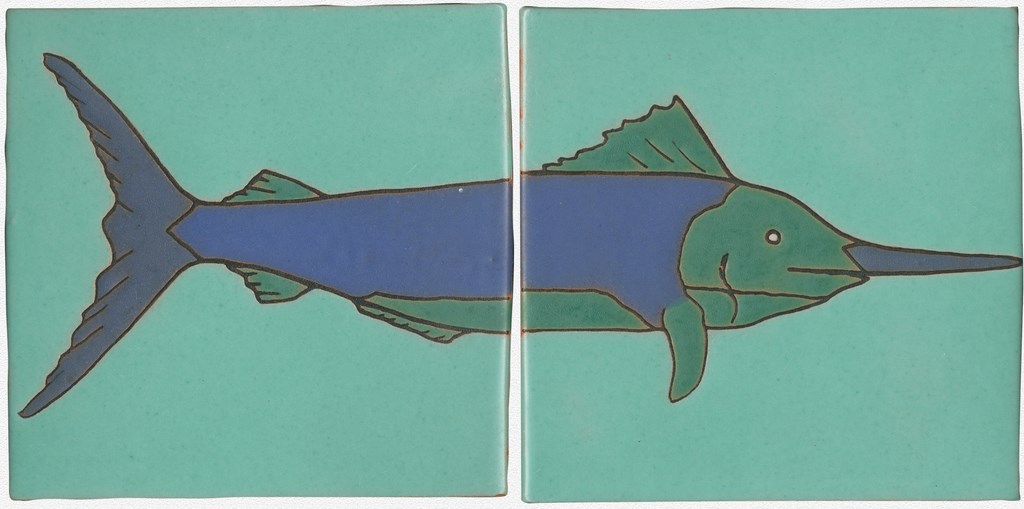

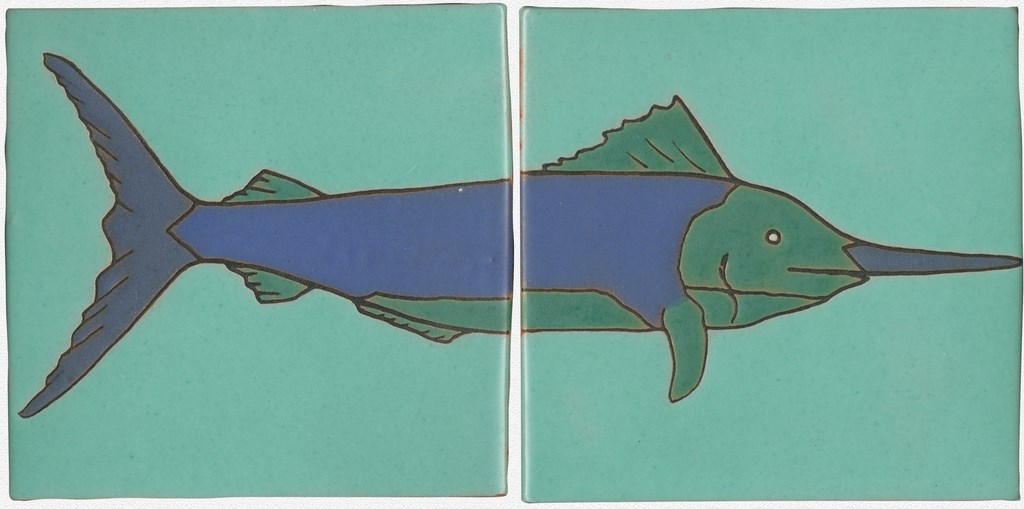

| I found this vivid tile at the Santa Barbara County Courthouse, which boasts one of the largest collections of original hand-painted tile of the early 20th Century to be anywhere in California. Created using traditional hand-painting techniques, this is a classic example of individual tiles used as a part of a large tapestry. |

But when we talk about tile, we’re considering a broad range of possibilities. On one extreme, it is the medium from which elaborate murals are made for public spaces – or it can be the entire inner surface of a watershape or a fountain in a private backyard. And tile is just as functional at the waterline of a pool as it is when used as a visual border to define the edges of steps or provide the most subtle of decorative accents for a wall or floor.

In my own work, I use tile to enliven and enrich a setting. I use it to add color, texture and patterns to a design, and/or to provide a project or a part of a project with a sense of historical connection, and/or to emphasize and highlight architectural styles and features. It also provides me with a way to pick up visual themes and create continuity between wet and dry areas or outdoor and indoor spaces.

| This is an example of newer tile that uses silk-screened line art with hand-painted cells. I used this in one of my Santa Barbara projects, choosing colors to complement the natural stone material we used throughout the exterior hardscape structures as well as the flowers seen in the courtyard space. This quatrefoil shape is an example of a pattern in which individual tiles can stand alone. |

For all of these reasons, I’ve made it my business to study tile and seek out its sources, both commonplace and exotic – and it’s always surprised me that more watershapers don’t do the same. I find that by studying tile, I am drawn into specifics about art and architectural history, and I’ve also come to know a thing or two about traditional tile-manufacturing processes and how they influence and contrast with techniques used today.

In other words, I love beautiful tile and capable tile work, and I’ve had a great deal of constructive fun studying it in most of its forms:

[ ] Painted by Hand: I’ll state up front that hand-painted tile is the type I find to be the most exciting. Unparalleled for sheer beauty and the richness it can add to otherwise commonplace objects, its capacity as a design tool is truly astonishing.

| These tiles were remnants from a project I’d worked on previously and now adorn this simple circular spa, which overlooks Abalone Cove in Palos Verdes, Calif. The exterior border reinforces the architectural lines of the spa without attempting to compete with the spectacular view. |

The world’s first hand-painted tiles originated in ancient Persia and were designed mainly for use in religious and imperial buildings. As adopted by Europeans and applied to other forms of background material (or bisque), painted tile has since been used to adorn many of the world’s most famous structures and continues to be a powerful visual tool for designers to this day.

The concept of “art tile” was particularly powerful in the last years of the 19th Century and the first few dozen years of the 20th Century, when the Arts & Crafts movement and Art Deco styles put all forms of tile and pottery in high demand and drew brilliantly skilled artisans to the craft.

| Glass mosaic tiles with iridescent colors were chosen for this swimming pool to accent spectacular views of the ocean and the surrounding landscape. The greens accentuate the indigenous and installed trees on the site, while the tans were chosen to complement stone used throughout the project. Note the geometry created by the dark green lines, which unify the pool’s steps and deep-end benches. |

The passionate and expressive designers of that era viewed tile as a canvas for representation of organic, natural forms and pursued avenues of design that broadened the palette of colors used with tile. To my mind, this was the Golden Age of hand-painted tile, especially when it came to development of applications in and around pools, fountains and other outdoor structures.

Nearly all hand-painted tile available today is based on the works of two influential firms that flourished in 1920s and ’30s, and I’m sure their names – Catalina Clay Products and Malibu Tile Works – are familiar to many in the trade. Although both of these Los Angeles-area firms are long defunct, together they defined contemporary hand-painted tile with respect to production techniques as well as patterns and styles, many of which are still available today.

| In a broader view of the setting seen just above, we see how the glass tile harmonizes with and maximizes the views and the natural materials used all around the water. |

Malibu tile is most closely associated with the Arts & Crafts movement, while Catalina tile usually comes up in discussions of Art Deco. Both are characterized by bold geometric patterns, but Malibu tile’s colors in the early years are somewhat subdued by comparison to the vibrant colors of early Catalina tile. Through the years, however, both companies produced tiles in a variety of colors and styles, and it’s often difficult to distinguish one maker from the other.

Basically, the tiles are built up in the same way as cartoon cells, with black-line borders filled by colored glazes before firing in kilns. The bisques were hand-formed terra cotta cut or worked into final shape, and the manufacturing process came to resemble an assembly line rather than an art studio once patterns were established.

| This band features a combination of glass mosaic pieces and limestone. The fact that the limestone pieces were much thicker than the glass led to installation nightmares, but the outcome is truly elegant. The burgundy of the flowers was chosen to complement the stained finish of the home’s exposed wooden structural elements. The limestone was used throughout the house, and we used some of the scrap here. |

Today, the 100-year-old creations of Catalina and Malibu tiles are still being made with only minor modifications in color or layout by dozens if not hundreds of tile suppliers. Indeed, the only real differences result from the nature of modern glazes, which have come a long way in the past century with respect to quality and the available ranges of colors. Now almost any color can be developed, for instance, and some artisans have developed glazes that “fade” beautifully from color to color.

[ ] The Art of Glass: For centuries, craftspeople have been hand-drawing glass for use as square tiles and mosaics. The Italians are particularly famous for their use of Venetian and Byzantine glass, which, in traditional processes, is melted and poured into thin sheets that are then cut into a standard module sizes. These glass tiles have been used for centuries in the creation of fine artworks that trace their lineage to the stone mosaics of ancient Rome.

| This address monument offers an example of using mosaic glass for both artistic and utilitarian purposes. The small, irregularly shaped pieces make tight contours possible without overly large grout lines. |

Venetian tile is distinguished by its modular layout in grids or squares and is a decorative hallmark of its home city, Venice. The modules typically range from three-quarters of an inch to an inch and a half and come in a staggering variety of colors. Venetian glass is also distinguished in many cases by an amazing iridescence that isn’t found in any other surfacing product I’ve ever seen.

Byzantine tile has historically been used to create illustrations or text of some kind and is often used to this day in creating such practical imagery as street signage along with figurative applications in monuments and other decorative murals. The glass modules are typically smaller than with Venetian glass – often only fractions of inches – and they’re made with irregular shapes suited to purposes of illustration and the assembly of mosaics.

| This modest pilaster was an element in a small project in Diamond Bar, Calif. – and a classic use of pre-cast tile that lets it play with light and shadow. These tiles are made using molded plaster – similar to the material used to finish pools. This type of embossed or textured tile is used almost exclusively on vertical surfaces because of the relative fragility of the material. |

Some of today’s suppliers produce glass tile in incredibly dynamic colors and textures, setting up foot-square sheets of Venetian glass with multiple colors and glazes to create a dynamic look that can be used in a variety of contemporary styles and applications – or prefabricating mosaic figures in Byzantine glass for applications on floors and walls.

[ ] Lasting Impressions: Molded and textured tiles are among the least used of all tile forms and are accordingly less familiar to designers and their clients. For the most part, these tiles have been used as decorative accents on vertical surfaces and more rarely as paving material, where they might lose the their texturing with time and wear.

| By way of contrast to the plaster tile, here we see an embossed tile used on both vertical and horizontal surfaces in a fountain in Naples, Calif. The tile is not used to call attention to itself, but simply accents fountain’s centerpiece. |

These tiles have a special beauty of their own and are finding their ways into more catalogs these days. In the past, they were made using a casting process in which wax or some other dense material was used to create an original that was impressed onto sand. Whatever material was to be used – plaster, clay, concrete or brick – was then poured into the mold, mirroring the textured surface. These days, however, the tile material is generally extruded, stamped and wire cut.

Frank Lloyd Wright was known among many other things for creating his own textured tiles by making molds and pouring concrete into them. Hollyhock House in Los Angeles is a classic example of this technique: Here, Wright used concrete impressed with stylized images of hollyhock flowers to create a theme that runs through the residence, inside and out.

| This embossed terra cotta tile is placed around about the floor in an erratic, Art Deco-style pattern, leading visitors down a hallway at the Santa Barbara County Courthouse. In this case, the tiles are distributed within a classic Spanish Colonial Revival paving pattern that easily allows for highlighting individual pieces of embossed tile. |

Today’s embossed or textured tiles are made with a range of enhanced and durable cement-based or composite materials that greatly increase the number of applications to which they are suited. There are indeed some beautiful products available these days, but there’s a downside in that some of these contemporary products look almost too perfect and crisp and lose the sense of authenticity and antiquity you find when you use a rougher or more distressed material.

[ ] Ceramics Class: Far and away the most common fired product found in today’s catalogs for almost any class of application – and especially those done in conjunction with water – is ceramic tile. Small producers and distributors of these tiles are everywhere, and I’m more than a little familiar with a two-mile stretch of road in Anaheim, Calif. (not far from where I live), called “Tile Row,” where you can find dozens (if not hundreds) of tile companies selling every imaginable sort of ceramic tile in tens of thousands of size, color and finish options.

| This is a case in which tile has been set up in a pattern intended to resemble the appearance of a Persian rug – the intention being to give this outdoor space the feeling of an exterior room. |

Ceramic tile is so common and used in so many applications because it’s affordable and especially resistant to water, which makes it perfect for bathrooms and kitchens as well as fountains, pools, spas and other outdoor structures of all kinds. It’s probably safe to say that 95% of all concrete pools have ceramic tile of some kind at the waterline.

Faux tiles, meaning tiles made to resemble some other type of material, represent the hottest trend in ceramic tiles today. These products are molded with a texture coat or silk-screened two or three times with various colors to look like slate (the most popular of the faux tiles I’ve seen) or travertine or limestone or granite. And they’re popular despite the fact that it’s probably less costly to buy the real thing – testimony to the fact that faux tiles have the advantage of coming in a predictable, consistent variety of sizes, shapes and colors.

TRACKING THINGS DOWN

As I suggested at the outset, I’ll stop at almost nothing to find the material I need to make a project achieve its full potential. It’s something of an obsession, and I spend a great deal of time poking around and looking for sources. Sometimes a search is complicated by the fact that many tile suppliers are small and serve specific regions, but just as often tile is to be had from vendors who ship their wares all over the world.

| This is an example of blue ceramic tile used in a waterfeature. Although this is not to my taste or preference, it’s a perfect example of the use of ceramic tile as a complement to glass block. |

Suppliers and distributors usually specialize in just one of the tile types detailed above and can help you find what you’re after once you’ve made your design decisions. It’s no secret that dealing directly with the manufacturer can save your clients’ money, but I’ve also found advantages in working directly with people who know how a tile I’m interested in was made, why it was made and how other designers are using it.

The Internet is a great tool in this respect. A web site might do no more than refer you to a local distributor for information, but in many cases the manufacturer will work with you and guide you through the design/specification process with superior knowledge of product characteristics and tolerances.

|

Seeing and Doing It’s nice to know something about your choices when it comes to finish materials, but those options are only truly meaningful if those you make or suggest to your clients are based on sound appreciation of a setting’s aesthetic and architectural values. To put it more bluntly, it comes down in large measure to context – and to whether you perceive what you are doing as a job or as making works of art. If you want to make art, here are some time-tested guiding principles: [ ] Understand the setting: To make the right choices, you need to be able to identify the architectural style of the surrounding structures and recognize the opportunities and limitations to which that identification leads you. If presented with a Craftsman-style structure, for example, you can assume that certain finish materials will resonate and that the organic forms and subtle colors of hand-painted or embossed tiles would be appropriate. You’ll also know that a Greek meander pattern at the waterline would be an immediate and obvious distraction when plopped down next to a Craftsman bungalow. [ ] Work with the design style: Knowing the components that make up a design style is the foundation of your own good design work. To use the Craftsman style as an example once again, you’d recognize the dark wood beams, stone cobble veneers and ornate copper light fixtures as elements that bind everything together. For those who know what they’re seeing, the misplacing or misusing of a single piece of that design vocabulary is tantamount to betrayal of Craftsman ideals. [ ] Make bold decisions: This is the single most important step in the watershaper’s journey, because there comes a point when we must reach beyond our immediate comfort zones and take risks. Sometimes we do so through choice of specific colors, textures or products, but more often it has to do with surprising people and playing to their preconceptions in a way that pleases and delights them with the knowledge that they know what you’re doing and why.Coming back to tile: Once you’ve made a design decision about which tile to use and in what configuration, it’s a matter of finding a source, getting a bid and acquiring the material. The key to unlocking that decision is being aware of what is available and not backing away from the hunt, secure in the fact that the effort will radically expand your ability to specify. — M.H. |

Good tile doesn’t come cheaply, either in terms of cost or the amount of time you can invest in finding just the right source. These factors obviously must be considered as part of the overall scope of work, as must the delays that often arise when you work with custom, hand-painted tiles or order special mixtures of glass colors for your clients.

With these special orders, tile may arrive in multiple small shipments over an extended period of time rather than all at once – a fact that definitely can halt you in your tracks on the job site if you’re not ready for it. As is true in many areas of custom work, I’ve found that taking steps up front to alert clients about possible delays in obtaining materials can save a good bit of stress down the line.

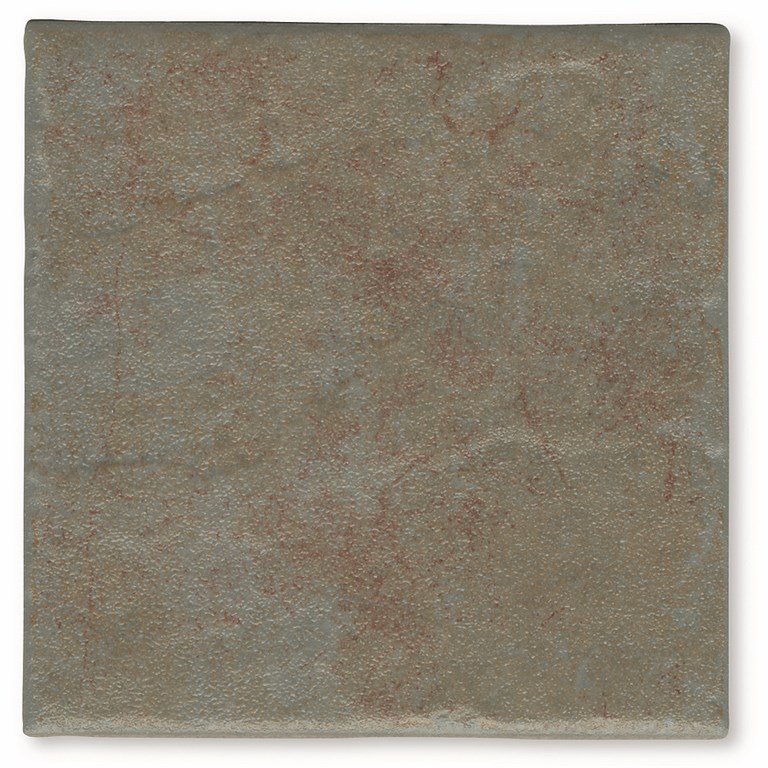

| This type of ceramic tile has become extremely popular in recent years. Although it’s not a material I’d choose over real stone in most cases, these tiles do a reasonable job of mimicking the subtlety of flat, natural stone. |

Why bother? The reason is simple: Tile and all of the other finish materials associated with watershapes are so vital to our art and craft that the right selections are worth the wait. It’s understandable that some in the business would come to rely on tried-and-true visual tools and readily available products, but following the path of the familiar seems to me to be a straight course to monotony, boredom and visual miscalculation.

In a sense, of course, these decisions about finishing touches are subjective, and some would argue that there is no such thing as a right or wrong usage of any material. But in painting a picture, there is no doubt that some strokes just “feel right.” This sense is a combination of exposure to the works of our forebears coupled with a basic understanding of design principles and listening to your heart.

When your choices are based on the balance of those mental processes, you’ll make choices that much more likely will stand the test of time.

Mark Holden is a landscape architect, pool contractor and teacher who owns and operates Holdenwater, a design/build/consulting firm based in Fullerton, Calif., and is founder of Artistic Resources & Training, a school for watershape designers and builders. He may be reached via e-mail at [email protected].