Liquid Glass

As a designer and artist, I believe that water and glass walk hand in hand: Both are transparent and translucent. They distort and reflect surrounding colors and forms. And depending upon whom you ask, water and glass are both liquids.

The visual and physical resonance between these two fascinating materials is important to me: I know that their interplay adds an entirely different dimension to my work that enhances the effects I can achieve using glass, metal and ceramics, so I’m always eager to explore artistic solutions when my customers want the project to include water.

In this article, I’ll examine three of my projects that use water to accentuate and reflect the sculpture while providing the soothing sounds that create an overall feeling of peacefulness in the surrounding space. But first, a bit more about what I do – and how I do it.

AHEAD OF THE GLASS

As with many forms of sculpture, working with glass requires technical know-how and, like many modern artists, I have acquired a background in construction and fabrication techniques.

Back in school my undergraduate studies emphasized math and science as well as art. Although I never figured I’d be able to make a living as an artist, my love for art and my need to create, build, invent and solve visual and technical problems in unconventional ways lead to a Masters degree in ceramics.

In the late 60s and early 70s, I worked as the director of the architectural department for a Dutch company called De Porcelyne Fles in Delft, designing and building large architectural murals. It was there, doing collaborative works with Leerdam glass, that I was seduced by the properties of the medium of glass.

|

Is It Really a Liquid? I’m often asked whether glass is a liquid or not, and I’ll attempt to answer that question here because the accompanying article is in part about the visual and aesthetic boundaries between water and glass. For years now, scientists and others have discussed and debated the notion that glass is an extremely slow-moving liquid. Some dismiss the idea as little more than an urban legend, but others point out that even though we generally experience glass as a solid, it also has some qualities of a liquid. Since Aristotle’s time, men and women of science have classified things as being liquid, solid or gaseous and have traditional rules that define those states. In general, the rules say that solids hold their shape while liquids and gasses do not. Because glass certainly appears to hold its shape while also exhibiting liquid-like behaviors, scientists have been forced to improvise a bit. Through the years, descriptions from plasma to vitreous state have been attached to glass. In a 1996 article, glass expert and researcher Florin Neuman called glass “an amorphous solid,” observing “a fundamental structural divide between amorphous solids, including glasses, and crystalline solids. Structurally, glass is similar to liquids, but that doesn’t mean that it is a liquid.” That’s dense enough to make sensible people wonder why anyone cares, but let me observe quickly that there are good, practical reasons why generations of scientists have tried to figure out what glass is all about. A friend of mine, a biologist specializing in the field of histology (which involves study of animal and plant tissues using powerful microscopes), practices what is known as ultramicrotomy, a procedure in which glass “knives” are used to cut or shave extremely thin tissue samples for examination under his microscope. He has observed that the edges on the glass knives appear “sharper” if they are used immediately after being made. The glass cutting edge, he says, soon appears to “heal over” just enough to alter the tool’s effectiveness. In my own work with glass, I’ve observed another characteristic that fits into this discussion. When I cut my thick sheets of glass, I do so by delete scoring the surface with a cutting tool. This sends an invisible shiver or shock wave through the entire thickness of the inch-thick material, causing it to break very precisely along the scored line when pressure has been applied. No other solid I’m aware of reacts in this way. And here’s another bit of trivia: Glass has no freezing point! Let me wrap up by saying that, on a purely aesthetic level and removed from the considerations of physicists and materials scientists, the internal visual quality of glass – its apparent liquidness – seems to align itself beautifully with water, a substance far more well known for its liquid qualities. It is the controlled visual movements of glass combined with the actual movement of water that encourages me to bring the two together whenever I get the chance. This is why, as an artist, I like working with water and glass. — J.G.L. |

Up to then, glass had been considered a craft material, and the most “artistic” work being done with the material was the province of glass blowers. As a natural offshoot of what I was doing professionally, I returned to Los Angeles (one of the great creative centers of the universe) and began studying glass blowing at UCLA, culminating in a Master of Fine Arts degree in glass.

It was during this period that I decided to put my technical background to use in the art world. I had it in mind to do big sculptures using huge sheets of thick glass. To make a really long story short, I developed a method for heating inch-think panels of glass in furnaces and bending those panels in unique and interesting ways.

I import one-inch-thick glass panels from a company in England and subject them to a deceptively simple process. After cutting them to the desired sizes and shapes, I lay them over a series of ceramic, steel or fiber molds that are carefully assembled and arranged in a massive furnace I built years ago with the help of a brilliant engineer, Dave Brunette of Mechtronics Resources in Oakland, Calif.

Once everything is positioned, I slowly heat the glass to about 1,500 degrees Fahrenheit, and the glass slowly drapes itself over the pipes and whatever other objects I’ve placed to support it. Then I gradually cool the glass and let it anneal for a couple of days.

I remove these bent panels and begin to alter the surfaces. On most pieces, for instance, I will mask them very carefully with tape to create lines and shapes on their surface in preparation for sandblasting. I then take these etched and bent panels and mount them in metal braces to create the finished works. To this basic process I can add colored glass, all sorts of lighting effects, an endless array of metal and ceramic components – and water.

THE ART OF SHAPING

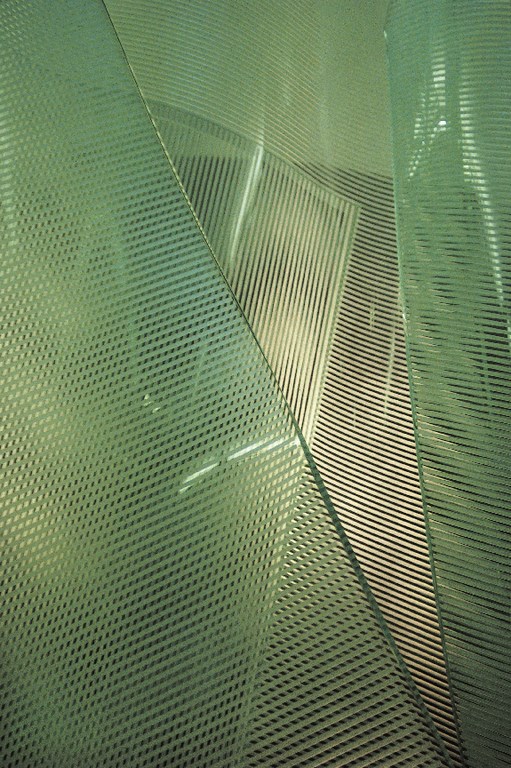

Aesthetically speaking, my primary concern is for what I call “linear form.” I am able to express lines and shapes both externally, with the physical contours of the cut glass panels, and internally, by way of the visual interplay among the layered panels and their etchings.

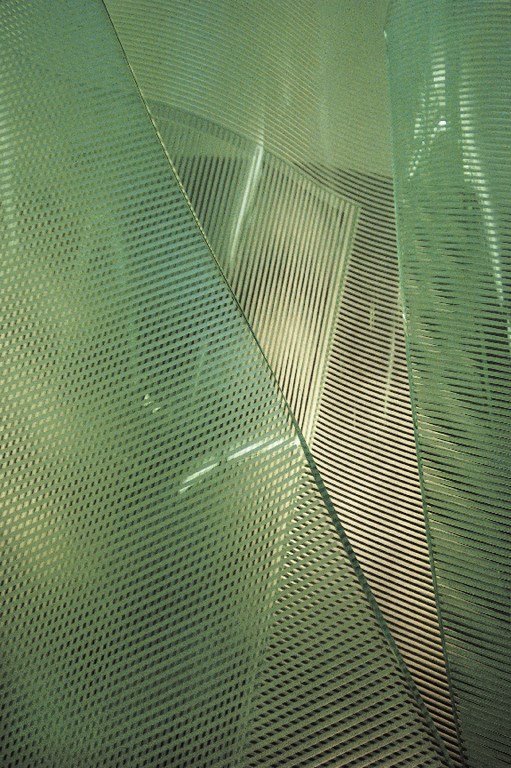

When I arrange the panels in layers, the effects can be spectacular: Light shifts as the viewer moves around the piece and changes perspective. This “internal space” within the sculptures adds another dimension in which I manipulate shapes and create interesting forms and lines.

|

Seduced by Shapes The interaction of lines and shapes is crucial to the work I do. I’ve been fascinated by geometric shapes for as long as I can remember, from building blocks influenced by the cubes, squares and triangles of Freidrich Froebel, to Euclidean geometry and trigonometry in high school and on to the art-historical approaches of the Bauhaus and the abstractionist movements of the 20th Century. I have always been intrigued by the inventive ways geometry and perspective have been “encountered” and used throughout this history. But my love of shape goes beyond geometry. Many of my works use gentle, sweeping lines that suggest natural forms and movement and reflect my deep and abiding love of and respect for the female nude. I believe the lines of women’s torsos, backs and limbs are among the most graceful and intriguing that exist anywhere in nature. I don’t work literally with this “source material,” but rather see those forms as the inspiration for the sweeping shapes and lines I use in my work. I use these lines to soften the effects of hard materials and to create a sense of balance and movement within my sculptures. Even in works that are obviously abstract or architectural in nature, I believe that the forms of nature are expressed in the contours and shapes that make up the work. No matter whether you’re an architect, a sculptor or a watershaper, I believe these sinuous, natural lines will inspire you to create works of extreme beauty and subtlety. — J.G.L. |

I get pretty excited by the work, and I’m always amazed at the endless number of things I can do with the medium. Exploiting this potential, however, takes time and patience.

In fact, when I’m designing these pieces, I plan their effects very carefully. I’m always manipulating and repositioning panels, keeping in mind the way they interact and watching what happens as I initiate changes in spacing, lighting, colors, textures and the surrounding environment. And I’m constantly changing my perspectives, too, moving around the piece and assessing what’s happening from all angles and at various elevations and lines of sight.

I’ve now been working with glass for more than half my life, and I think I am beginning to understand its absorptive, reflective, refractive, transparent and translucent qualities. I apply that understanding as I go, and I find that the external simplicity of the shapes I create become more complex the longer and deeper you look at the work.

As the etched and overlapping lines and forms intersect within the piece, they become the piece. Shapes appear and dissolve as you move around them, and each assemblage of individual panels ultimately creates its own internal space with a visual language all its own. And because glass is transparent, the surrounding environment inevitably gets involved: Adjacent structures or landscapes are distorted and “interpreted” within the lines and forms of the piece.

The effects can be startling as the mind’s eye opens to take them in. As the observer learns the language and perceives what’s happening, the effects take on a depth and complexity that keeps drawing you in.

Through the years, I’ve done a variety of projects, several for public or commercial clients, some for private residences and many that exist solely for the sake of my own personal expression. Some of my work is political; some of it is deliberately sensual or even sexual. Oftentimes it is meant to convey emotions running the gamut from anger and conflict to love and acceptance.

I like to think that none of it is boring.

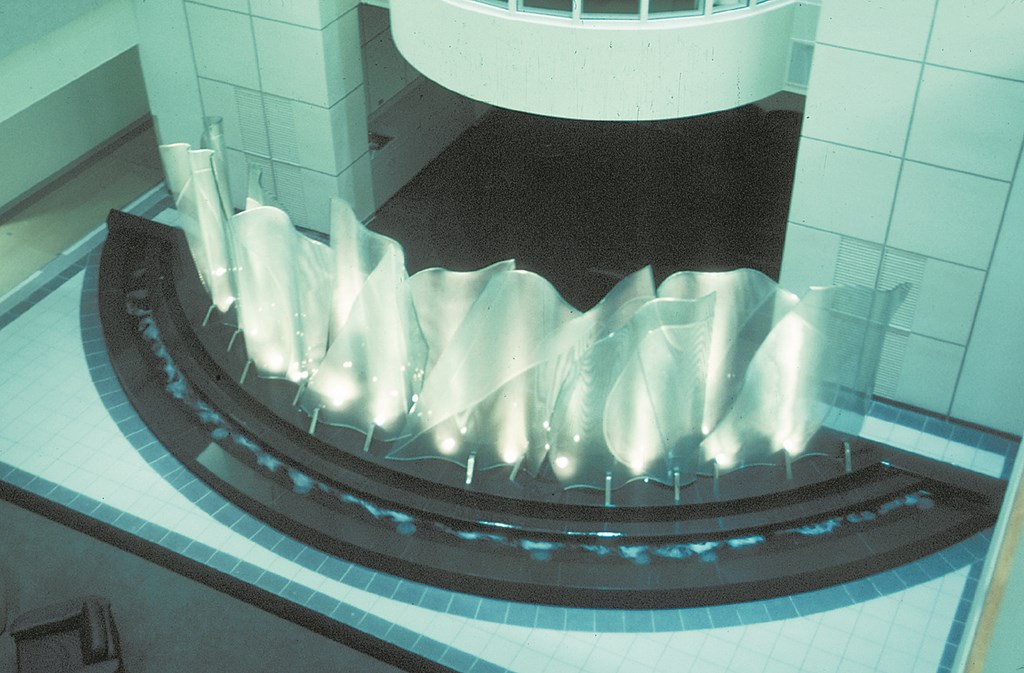

The Scripps Research Center

This piece was completed in April 1996 for the Arnold and Mabel Beckman Research Institute at the Scripps Research Institute in La Jolla, Calif. The panels stand 11 feet tall and are mounted atop a black absolute granite base that appears to float on water.

The piece consists of 12 geometric shapes of inch-thick slumped glass. The overlapping panels work to create a variety of geometric shapes that exist only when you move past it and observe the striped, quarter-inch etchings and the variety of moiré patterns they create along the 40-foot arc.

The water comes out of an arcing weir set below the sculpture and flows very gently over a step in the granite base into a narrow trough. Its effects are both visual and aural: The gentle movement and highly reflective surface work in perfect harmony with the undulating glass panels, while the soft sound of the falling water creates a meditative ambiance in the area around the piece.

That was right in line with the objectives of the people at Scripps, who wanted something that would be visually evocative – yet gentle and meditative.

This is a major research facility and the atmosphere and work can be extremely serious and intense. The trustees wanted those who work there to be able to come out of their labs into this atrium area to relax in a beautiful environment. Yes, the piece is massive and formal, but that sense of control and discipline is thoroughly balanced by its soft, gentle lines and the soothing sounds it makes.

Soft white lighting emanates from a series of fixtures mounted in the black base, highlighting the sensuous curves and lines of the panels.

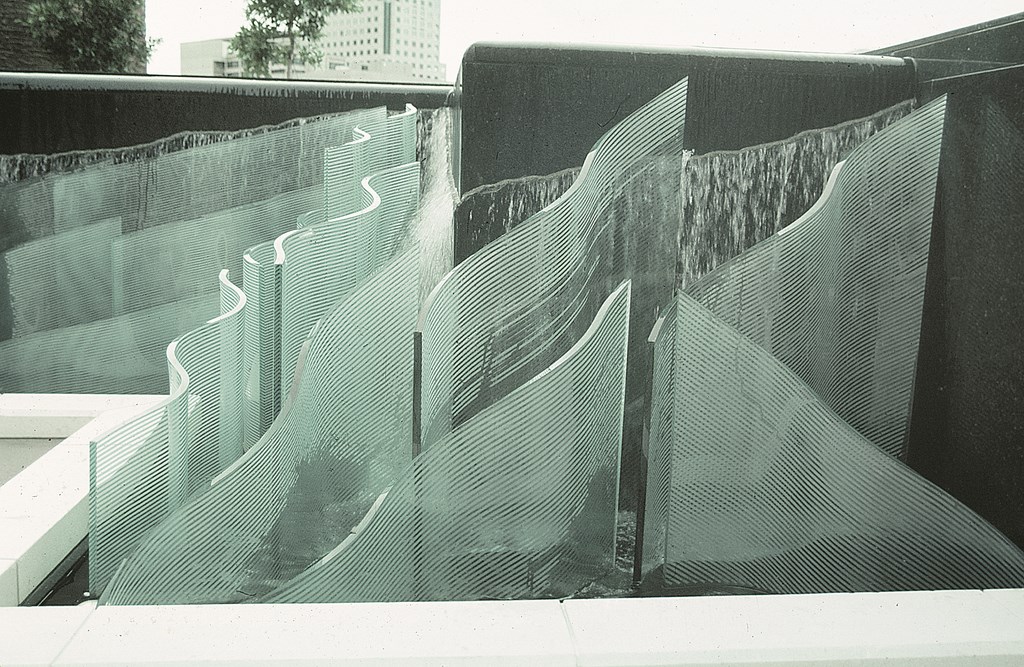

Barker Patrinely

This linear fountain was completed in November 1988 in conjunction with a beautiful 23-story high rise in San Francisco. The work stands in a garden atop a three-story parking garage next to the building. Access to the space comes through the building lobby as well as from the street.

Slumped glass panels are located in two separate waterfeatures: a 12-by-12-foot reflecting pool and a 45-foot fountain.

A seven-foot wall of Urazuba granite backs the big fountain. Water breaks over a weir at the top of the wall and falls down its face, where the sheeting effect is disrupted by breaks in three layers of the one-inch granite sheets. The motion of this water is visible through the layers of glass and works to create a complex set of interrelationships among the contours of the glass and the etchings.

The sound made by the overall composition is important here. Masking of the traffic noise below was one objective, and that’s taken care of by the almost visceral sound made by the water as it breaks on the layered granite sheets. But because this action takes place between the granite and the glass panels, there are echoes, reverberations and distortions of the strong, primary sound that create a sort of rolling rumble that is actually relaxing rather than jarring.

The visual shapes and textures of the fountain are echoed in the reflecting pool. The low-profile panels rising out of its water demonstrates the seamless relationship that can exist between glass and water.

This work was done a time when very few people really appreciated glass or saw it as a viable sculptural element. I credit the architects and the owners for having the courage to do something truly unusual.

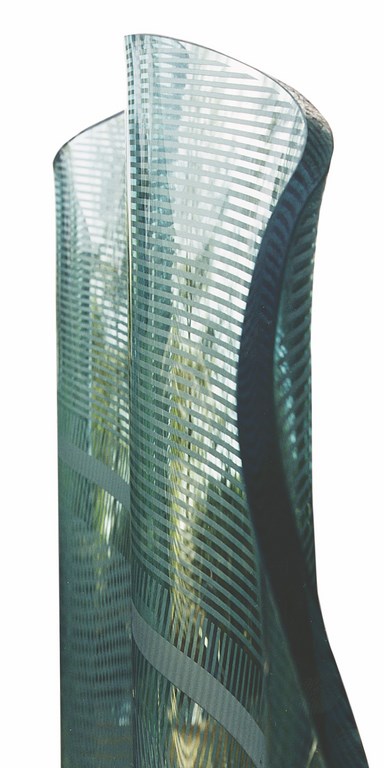

Private Residence

This is my most recent foray into sculptural work with water. Installed in June 2000, this fountain piece was created in conjunction with a spectacular backyard project designed and built by David Tisherman. (For details on the overall project, which is now complete, see WaterShapes, February 1999, page 22, and April 1999, page 48.)

The owners wanted something truly unique in their backyard – something that would make a distinct artistic statement while working with the beautiful surrounding greenery and the pool.

The three glass panels sit on a square absolute granite pedestal. Water rises as a motionless sheet around the sculpture’s base, spilling over on all four sides into a trough filled with smooth black and dark-gray stones.

The piece itself evokes basic geometrical shapes – triangle, circle and square – that pick up and echo lines found in the swimming pool and surrounding structures. The water flowing beneath the panels reflect the foliage of the surrounding eucalyptus trees – also reflected and distorted when viewed the through the glass.

As with many of my designs, this piece offers a changing set of views as you walk around it. Combined with the etching, the outer contours of the panels themselves take on different shapes and appearances when viewed from different angles.

On this job in particular, the use of a scale model was all-important. During the design phase, the owners were having trouble visualizing what I was trying to do – and I have to admit that it’s not easy to use words and two-dimensional renderings alone to describe the multi-dimensionality of the work I do. Where other forms of sculpture offer only exterior dimensions and shapes, mine are transparent and translucent and also have this complex set of interior dimensions and forms.

We soon saw that the only way to help everyone visualize the work was by way of a model: I built one to scale (an inch to a foot), complete with the glass etchings and the fountain base, and brought it over to explain the effects I was trying to achieve. We even took the little thing out and put it in the yard at the spot where the finished piece was to go. Now they were able to walk around the yard and the model and get a sense of the shifting profile and shapes I was pursuing.

This visualizing process had the further effect of helping us decide to orient the piece so that it presented a very frontal, almost flat, view from the main rooms of the home. As you move into the yard and walk toward the pool, the perspective shifts and your eye is led from the sculpture itself into the surrounding environment.

John Gilbert Luebtow is a highly regarded modernist sculptor based in Chatsworth, Calif., and has designed and constructed massive glass sculptures in architectural settings for nearly 30 years. He holds advanced degrees in ceramics, glass and fine art from the University of California at Los Angeles and California Lutheran University. His portfolio includes elaborate commissions for commercial clients including Atlantic Richfield, MCI, the Supreme Court of Nevada and the Yokohama Royal Park Hotel in Nikko, Japan, among many others. Among his most striking works are those that include the use of water as a design component.