Islands Afloat

The very existence of floating islands seems counterintuitive. Are there really chunks of earth solid enough to support our weight while drifting over the surface of a body of water? Can these floating masses even support the weight of trees, animals or even human dwellings?

The fact is that floating islands do exist on six of the seven continents and sometimes on the oceans between. Some do have trees growing on them and do support the weight of humans (and even grazing cattle). Some are, in fact, hundreds of feet across and are called “home” by their inhabitants.

These naturally occurring, waterborne vessels embody a fascinating subset of natural observation and are generally unknown – even though they play important ecological roles and have intersected human history in sometimes surprising ways.

FROM THE ANCIENTS

Made up of light, buoyant, spongy tissues of certain species of aquatic plants or, alternatively, suspended in place by gases released into their soil by decomposing vegetation (or by both factors), floating islands have attracted the attention of writers and philosophers since antiquity.

In one early instance, 1st Century Roman writer Pliny the Younger (in his Epistles, 8.20) provides an evocative description of the floating islands in Lacus Vadimonis, now a marshy pond known as Lago di Bassano on the bank of the Tiber about 40 miles north of Rome.

| Figure 1: The floating island in the Lago di Posta Fibreno southeast of Rome. (Photo by Antonio Lecce) |

He writes: “No boats are allowed on the lake, as its waters are sacred; but several floating islands swim about it, covered with reeds, rushes, and whatever other plants the fertile marshy ground nearby and the edge of the lake produce. Each island has its peculiar shape and size, but the edges of all of them are worn away by their frequent collisions with the shore and one another.”

Pliny’s observation about the edges of the islands being worn away by collision accurately describes a common characteristic of floating islands found in lakes to this day. Included among this battered legion are the floating islands in the lakes of the Upemba Basin on the Lualaba River system in Zaire; in Orange Lake in Florida; in the Iberá Wetlands near Corrientes, Argentina; in the Lago di Posta Fibreno southeast of Rome (Figure 1 above); and on the surface of the Zacatón sinkhole in Tamaulipas, Mexico (Figure 2).

| Figure 2: Floating islands on the surface of the Zacatón sinkhole in Tamaulipas, Mexico. (Photo by Marcus Gary) |

It wasn’t until the 17th Century, however, that serious inquiry into the nature, formation, and buoyancy of floating islands began. Claude Dausque, who was familiar with the floating islands that once existed near St. Omer in France, started the ball rolling in his obscure but compelling book, Terra, et aqua seu, Terrae flutantes (published in Tournai in 1633 and again in Paris in 1677).

In Italy, the Jesuit polymath Athanasius Kircher studied floating islands as well, finding his in the Lago della Regina (then called Lacus Albuneus or “la Solfatara”) near Tivoli. He concluded in his Mundus Subterraneus (Amsterdam, 1665) that floating islands form from conglomerations of bituminous, sulfurous and nitrous particles. (An interesting concept, but incorrect.)

ON TARGET

Several generations later, a particular floating island in England helped scientists recognize the importance of the gases released by decomposing vegetation to the buoyancy of floating islands. Derwentwater, a lake in England’s Lake District, was famed for an intermittent floating island that appeared only following hot summers, always in the same spot (Figure 3). Some had argued that upwellings of water from a stream that flowed into the lake were what buoyed this island.

Victorian scientists took a studied interest in the problem, and Jonathan Otley, author of a famous guidebook to the Lake District, took samples and determined that gases from the decomposition of vegetation were responsible for the island’s rising. A hot summer, he observed, would increase the rate of decomposition, thus generating more gas that would make the “island” (actually a section of the lake bottom) buoyant enough to rise to the surface.

| Figure 3: The author atop the intermittent floating island in Derwentwater, Cumbria, England. (Photo by Sandra Sáenz-López Pérez) |

Toward the end of the 19th Century, the gases in a similar floating island in Lake Ralången, Sweden, were also analyzed, and similar conclusions were reached.

Through history, floating islands have been known commonly to rise in newly flooded reservoirs. If the flooded area has peaty soil (meaning it has lots of decomposing vegetation), the filling of the reservoir will make certain types of peat buoyant. If the water is deep, its weight will hold the peat in place; if it’s shallow (less than six or seven feet), the buoyancy will allow sections of peat to tear away from the bottom and rise as floating islands – many of enough substance that they can be colonized by various plants, including trees.

In reservoirs raised to feed hydroelectric generators, these islands can cause serious problems if they are drawn into the intake systems. Removal is difficult and expensive, but awareness of the phenomenon has made it practical in some cases to prevent or mitigate this problem before flooding by burying suspect areas with gravel.

Sometimes these islands emerge with a rise in water level. If there is an area of peaty soil at the edge of a lake (which has gases suspended in it from decomposing vegetation) or a stand of cattails or papyrus (which have buoyant roots), the rising water breaks sections of these edges free of their former positions – processes assisted by wind and wave action.

GLOBAL EFFECT

Given the multiple forces at work in creating these islands, it comes as no surprise that floating islands are truly a global phenomenon.

In tropical lakes, for instance, floating islands can form from masses of floating vegetation such as water hyacinths (Eichhornia crassipes) or Salvinia molesta. These plants have special tissues that cause them to float, and in the right conditions they grow quickly to form large floating mats. Through time, plant detritus and dust will collect on these mats and alter them into quite solid form.

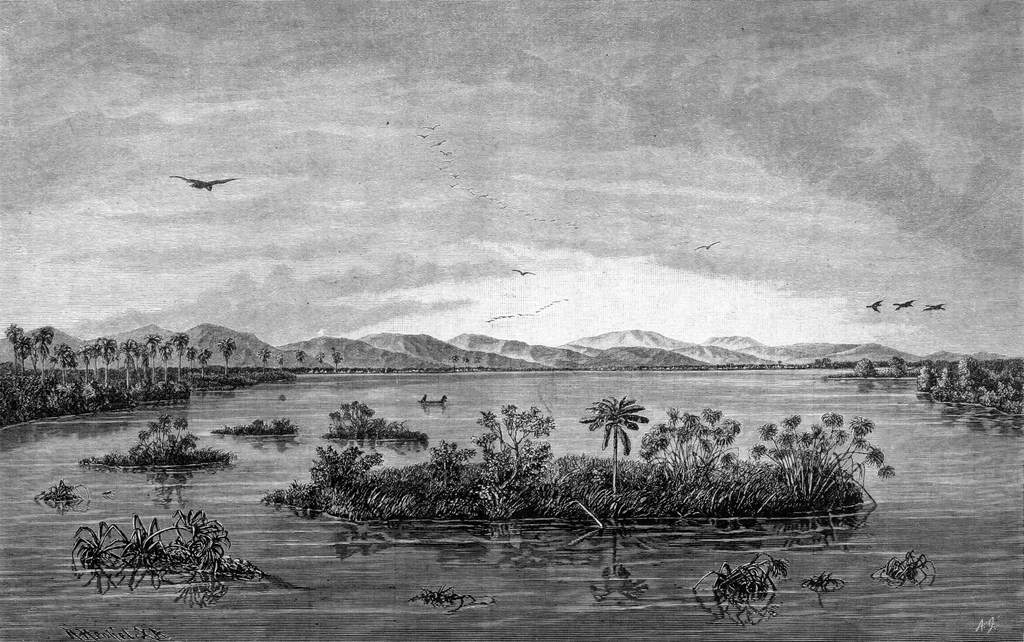

| Figure 4: Woodcut illustration of floating islands in the Congo River by A. Goering, 1883 (from the author’s collection). |

Floating islands also emerge during floods of the great tropical rivers of the world, when large masses of aquatic vegetation or chunks of bank are torn away and carried downriver. This often happens on the Congo River in Africa (Figure 4); in some cases, floating islands that navigated their way to the ocean were sighted 150 miles out to sea beyond the river’s mouth.

Similar landmasses are also common within and beyond the Sepik River in Papua New Guinea following monsoon rains. These islands are called “lik lik aislans” in Pidgin English, and can be up to 330 feet across with still-living trees on them.

The Río Paraná and Río de la Plata in South America also generate floating islands. These are called camalotes and are basically matted masses of water hyacinth. A famous incident on the Río Paraná at Convento de San Francisco in Santa Fe, Argentina, involved the killing of two friars at the Convento by a jaguar that arrived in town on a camalote on April 18, 1825.

|

Ancient Perspective Pliny the Younger’s observation of floating islands near the Tiber river north of Rome led him to great eloquence. Continuing on with the passage following the one quoted near the start of this article, he writes: “They are all of the same thickness and buoyancy, for their shallow bases are shaped like the hull of a boat. This may be clearly observed from all sides: The islands lie half above and half below the water’s surface. Sometimes they cluster together and seem to form a little continent; sometimes they are dispersed by the shifting winds; at other times, when the wind falls dead, they float in isolation. “Often a large island sails along with a small island joined to it, like a ship with its tender, or as if one were striving to out-sail the other; then again they are all driven to one spot on the shore, whose limits they thus advance; and now here, and now there, they diminish or restore the area of the lake, until at last they occupy the center again and so restore it to its usual size. “Sheep, seeking grass, proceed not only to the shores of the lake, but also upon these islands, nor do they perceive that the ground is mobile, until, far from the shore, they are alarmed to find themselves surrounded by water, as though they had been suddenly conveyed and placed there. Afterwards, when the wind drives them back again, they as little perceive their return as their departure.” — C.V.D. |

A 1905 flood on the Río de la Plata filled the waterway at Buenos Aires with camalotes as far as the eye could see – some a half-mile long and 100 feet wide, others just a few feet in diameter. As they came down the river, these islands had enough mass and momentum to rip ships from their moorings.

And the islands brought passengers with them, including snakes, deer, a puma, parrots and monkeys. An Indian baby was found on a floating island that came ashore near Rosario, and although he was weak from hunger and exposure (the flood occurred in July, which is winter in the southern hemisphere), he was brought back to health.

Most floating islands that come down rivers end up in the sea, where many are quickly destroyed by waves. Although some survive for quite some time, accounts of floating islands seen at sea are rare but fascinate evolutionary biologists, who see them as means by which plant and animal species may have been dispersed across oceans.

BOUYANT HABITATS

One would assume that floating islands provide refuge to animals during floods, but it has also been observed that they also provide important habitats during calmer times.

| Figure 5: The phumdi or floating islands of Loktak Lake, Manipur, India. (Photo by C. L. Trisal) |

Several species of birds – terns and ducks, for example – nest quite happily on floating islands and enjoy the relative degree of protection they provide from predators. And because the islands rise with the water level, nest flooding is much less of a problem. In addition, the undersides of floating islands, which often have roots hanging down, provide sanctuary for fish.

People can live on floating islands as well. Loktak Lake in Manipur, India, has a huge number of natural floating islands known as phumdi (Figure 5 above), and the locals commonly reconfigure them as platforms for fishing. They assemble various pieces of phumdi into ring-shaped assemblies with diameters of 650 to 800 feet and surround them with a netting that reaches to the lake bed to corral the fish. They then stir the silt with bamboo poles to deoxygenate the water and bring the fish to the surface where they’re easily caught.

Beyond that, many fishermen and their families live in huts called khangpok built right on the phumdi of Loktak Lake. In 1986, 207 khangpok were reported on the phumdi; by 1999, this number had risen to 800 – an increased population that has put unfortunate pressure on the lake’s ecology.

|

A Seafarer’s View A story published in several newspapers in June and July of 1902 gives a remarkable account of two floating islands spotted at large in the Caribbean. The Norwegian ship Donald, steaming from Banes, Cuba, on its way to Philadelphia, encountered a floating island about 30 miles from the island of San Salvador: “On passing Watlins Island, which lay off about 30 miles,” said Skipper Warnecke, “we steamed close to a floating island. Upon it were what appeared to be a large number of stately palm trees. I had never encountered anything like this in all my seafaring life. “The floating island was moving, and that, too, at a slow rate. Curious for a thorough investigation, I steamed still closer to the object and was amazed to find what I took to be palm trees were full-grown cocoanut trees, and laden with fruit of the largest kind. Then I ordered a boat lowered and, together with the first mate, made a landing on the still-moving island. “Then another surprise awaited us. High up in the trees was a small colony of mischievous monkeys, and as we got nearer they shied a number of cocoanuts at us. After a lot of trouble we secured two of the attacking simians and at least a dozen cocoanuts. Then we took to our boats, boarded the steamer, ordered full steam ahead, and soon the strange floating island was lost in the haze astern. “But another surprise was in store for us on the following day, when we passed within glass-sight of another singular floating object just off the port bow. The lookout sung out ‘Land ahead.’ This amazed me, for I knew according to the chart land was not miles near. Still, curious from the previous day’s experience, I determined to solve this further mystery of the sea, so I gave orders for the ship to steam close to what I now made out to be another floating island. Again I had a boat lowered, and with the same crew we landed on the island. “We found it to be an exact duplicate of the day before, with this exception – instead of monkeys we found a big covey of parrots of most brilliant plumage. Among them was one who was evidently the patriarch of the tribe, and I do not exaggerate when I say that the aged fellow could cuss in two languages. He was evidently a lost pet. We took him and a couple of his fellows aboard the steamer, and soon left the floating island in the distance.” — C.V.D. |

There are other parts of the world where people live or have lived on floating islands. Some 6,000 people live, for example, on the floating islands or sudds that move freely about Lake Kyoga in Uganda. These islands are large floating masses of papyrus that originate in the swamps along the lake’s shore; when the water level rises, large sections of matting are torn free to float out into the lake.

Other floating islands flow into lakes along the Nile. Some of the inhabited sudds are very large. One in particular is big enough that it takes two hours to row around it in a canoe. But life on the sudds is difficult: Malaria is rampant, and the lake waters are both the islands’ sewer and their source of drinking water. The islands are buffeted by high winds, and the lake is large enough that waves are an issue. Even though the inhabitants maintain their islands by adding papyrus to their surfaces, the sudds do not last more than five years.

Naturally many of the islands’ residents are fishermen – and very few are women. On Lake Kyoga, there’s also an element of the Wild West: The lake is divided into 13 districts, and because the islands move unimpeded from one district to another, jurisdictional issues are rampant and has led to the islands become a refuge for those who face problems with the law.

NATURAL SURPRISES

This has been just a quick overview of the natural history awaiting discovery in the world of floating islands. Although they strike most people as little more than a natural oddity, it’s clear that by understanding the nature of these surprising buoyant masses, we learn much about the nature of aquatic environments, biology and, possibly, our evolutionary history.

In that sense, it’s not such a reach to suppose that a time will come when watershapers will start looking to man-made floating islands as part of their milieu, either as the object of environmental fascination or as an unusual garden-pond environment that can support human occupation.

Whether this study is for professional inspiration or simply in the spirit of understanding the fullness of the amazing world of aquatic environments, it’s clear that floating islands should be part of our collective passion.

Chet Van Duzer is an author based in Los Altos Hills, Calif. His past works include examinations of sinkholes, ancient literature and the history of cartography. His most recent work – and the one most relevant to watershaping – is the book Floating Islands: A Global Bibliography, published by Cantor Press. He may be reached at chetv@aol.com.