Interior Splendor

Working outdoors in the California sun is typically seen as a desirable perk, especially when, as in this case, the on-site alternative was working below ground in a confined labyrinth of narrow passages with limitless opportunities for banging your head. But here, it’s my general sense that the plumbers working below ground on Hearst Castle’s Neptune Pool (San Simeon, Calif.) had an easier row to hoe than did the marble applicators working in the open air.

For one thing, tasks performed on the interior surface of the pool were all about aesthetics and history and authenticity from Day One on the job site. With countless state, park and facility officials watching every move to make certain what came out was replaced with something virtually identical going back in, the pressure was ratcheted up a twist or two.

For another, the level of craft required to remove and identically replace a football-field’s worth of patterned marble tile on a surface marked by curves, undulations and corners – not to mention myriad penetrations – was simply off the charts with respect to attention to detail, fineness of the work and patience with a difficult material.

It’s all done now, but it’s small wonder it took more time to complete the work than anyone hoped or anticipated.

CLEARING THE FIELD

The three articles preceding this one all lead up to the point where the biggest problem faced by those who worked on restoring the Neptune Pool to full functionality and splendor had to be confronted – that is, fixing the cracks that had been allowing the pool to leak to the tune of 5,000 gallons a day in drought-stricken California.

When the swimming pool was first completed in the 1920s, it was much smaller than the current Neptune Pool – appropriate to Julia Morgan’s smaller-scale early work on the Hearst estate but later out of place once the structures on the Enchanted Hill took full, majestic form.

Morgan revamped the pool starting in 1934, stretching its small oval form into a rectangle with Grecian-style ends and a raised fountain bay, thereby leaving the new structure with long cold joints where new concrete ran up against remnants of the original shell. The big pool probably always leaked to some extent, but an earthquake had turned drips into steady flows that required more than makeshift remedies.

| Once the original marble finish had been chipped away, it was easy to see both the cold joints (top left and middle left) as well as the cracking that had occurred through the years (top middle right). We cut out sections that had suffered the most damage (top right) and made ready to apply new concrete (bottom left); we also prepared for injection of polyurethane to fill and stabilize minor cracks (bottom right). Through it all, we took comfort in the fact that the entire interior surface was to be coated with a waterproofing agent. |

Pursuing the shell repairs required removal of large sections of marble tile from affected areas over the cold joints and cracks – and this is when it was confirmed that the marble had begun to deteriorate to a point where pieces couldn’t readily be removed intact for later reinsertion. So complete removal and replacement came onto the agenda and, as luck would have it, material was still available from the same Vermont quarry that had originally helped Morgan pursue her vision eighty years earlier.

Adding to the difficulty was the fact that the tiles had been expertly installed back in the 1930s: The bonds to the substrate were still tight, and it was nearly impossible to break the tiles away from the mortar bed without damaging individual pieces. This factor even made it impossible to salvage even the dark-green accent tiles, which were in better shape than the light-gray/white field tiles: Breaking out the lighter pieces had a tendency to damage the adjacent darker pieces, so it all had to come out.

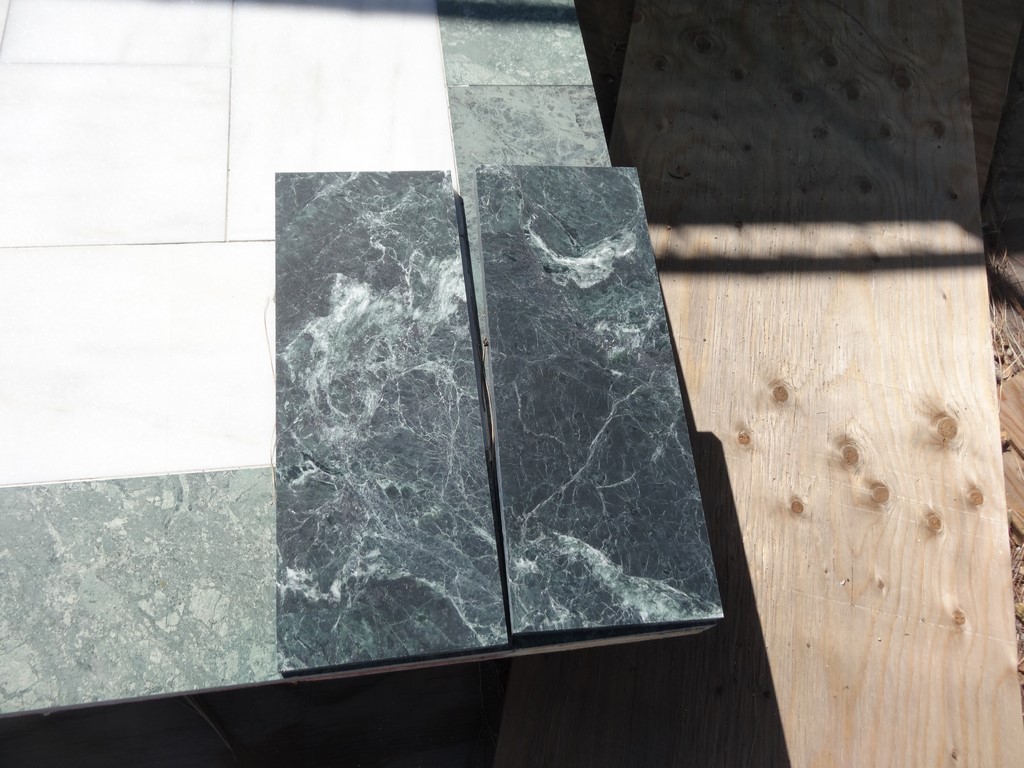

| One of the hurdles the marble applicators faced was demonstrating to various officials that what they were going to do within the restored shell would be an utterly accurate, faithful rendition of what had been there originally. This required the laying out of sample sections for examination by critical eyes; it also meant that, in the pool, dry-fitting was an absolute necessity, particularly given the effect the addition of waterproofing had on the pool’s interior dimensions. Piece by piece, section by section, the finish began coming back together. |

Then there was the fact that the marble contained traces of asbestos: Not only was it difficult to remove, but now the operation had to be completed with incredible care to prevent the release of hazardous fibers to the detriment of workers and the local environment.

To be sure, there were advantages to cleaning the slate, most of them related to the desire to waterproof the entire surface. But given the strong sentiment that what could be preserved should be preserved that drives historical restorations, all recycling possibilities had to be considered before, in this very specific case, the desire to salvage as much original marble material as possible could be dismissed.

MAKING HEADWAY

With the pool’s interior cleared to the shell, we moved into the crack-repair operation by cutting and removing the section of the shell most seriously damaged through the years. This was the deepest part of the pool, which helped the plumbing crews by eliminating their need to core-drill larger holes for the new, larger-diameter drain pipes.

Given the age of the shell and the fact that settlement was seen as a completed phenomenon, it was decided that simple polyurethane injection could be used in crack repair rather than the more intensive epoxy-injection approach. Lending weight to this decision was the fact that the entire pool was to be treated with a waterproofing system that would seal the surface and eliminate leakage via any small fissures that might form in the future.

| Among the most complex of the tasks inside the pool had to do with cutting and fitting marble pieces over and around various penetrations. As can be seen at left and middle left, the applicators worked around these obstacles, waiting until all other details in the surrounding surfaces had been settled. It was a difficult material: Some solutions would be relatively easy – others not so much. |

Of course, the addition of a waterproofing layer fractionally changed the internal dimensions of the pool – a thought that had a sobering effect on those who would be making tiny cuts to some marble pieces to make the joints work properly. That sort of knock-on consequence is always lurking around unexpected corners in a process like this, but in this case, it was a very big deal indeed.

The issue here was that the tile, for various reasons related to budget, had been cut to standard sizes at the Vermont quarry before shipment to California. This meant that small adjustments to gain perfect fits had to be made on site while working with a material that’s inclined to split, crack and slough off layers in unpredictable ways as a result of its sedimentary structure. Again, this was not easy work.

But because this was to be visible work, the level of scrutiny was remarkably high: Sample sections of patterns had to be prepared for comparison to photographs of the original, and there were even cases where those samples had to be prepared on contoured surfaces to show just how things might be done.

It would be easy to dismiss these trials as a waste of time, but they were actually valuable to the application crew: Through these exercises, they learned approximately what they would be up against in working with the marble and came to their labors in the shell armed with information that guided their approaches to the complex tasks at hand.

One thing they learned is the obvious fact that, while a piece of marble can be trimmed to fit if it’s too big, it’s definitely impossible to stretch it to fill a gap. This is why dry-fitting was always such an important part of the application process: There was an absolute need for tight joinery, and the time to make adjustments in layout was a point well before the mortar bed was ready!

As work on site came to a close, there was one more big event that had to precede refilling the pool: All of the sculptures that had been removed from the area around the pool and the pool’s fountain needed to be returned to their various perches and, subjected to their own restoration/stabilizing treatments, made ready for fresh exposure to wind, water and sun.

READY FOR VIEWING

Once the preliminaries were completed and the pool had been drained to start the renovation process, we arrived on site in the spring of 2015 and figured our work there would be completed at some point in the spring or summer of 2017. As it turns out, another full and busy year passed before the project was completed and refilling began in August 2018.

There are all sorts of reasons why it took longer than anyone thought or hoped, not the least of which is that installing patterns of marble tile across such an immense canvass is just hard work that, in this case, had to be done to absolute and utter perfection.

| With time and incredible patience, the pool’s interior surface came together and we all developed a sense of unfolding magnificence, from the large fields of patterned stone to the elegance of the gutter system. Gradually, all the work flowed into the pool’s deepest section, where the surface contours slowed things down and made the process even more deliberate and painstaking. |

We at Terracon (Olathe, Kans.) entered the process familiar with the nature of historic restorations and the stakes of playing the game at such an elevated level, but we found the work at Hearst Castle interesting as well as challenging – and genuinely enjoyed both the nature of the processes and the opportunity to see at first hand just how amazing the Neptune Pool is while also celebrating the genius of its designer, Julia Morgan.

Beyond all the practicality and wisdom we mustered under the pool and on to the beauty and artistry we were surrounded by in the open air, we had an opportunity to help preserve a glorious, legendary swimming pool for generations to come. As sources of pride and satisfaction go, I’m not certain we’ll ever top this, but I know we’re prepared to try!

This is the fourth in a sequence of articles on the renewal of the Neptune Pool.To see Part 1, ‘Assessing a Masterpiece’ by William N. Rowley, click here.For Part 2, ‘Defining Delicate Tasks’ by William N. Rowley, click here.For Part 3, my article ‘Beneath the Shell,’ click here.

Matthew Reynolds, P.E., is Department Manager – Professional at Terracon’s office in Emeryville, Calif., where he oversees the aquatics production team for the firm. A graduate of Loyola Marymount University in Los Angeles with a bachelor’s degree in civil engineering, he is professionally licensed in Arizona, California and Colorado. At Terracon, he acts as the main point of contact with clients through all project phases, from the initial request for proposal to completion of the construction process. He may be reached at matthew.reynolds@terracon.com.