In Service of Trees

I recently read a short article in a construction magazine in which the writer described a fairly convoluted process by which he had “protected” a tree on the site where he was working. Basically, what he did was wrap the trunk in two-by-four studs, securing them in place vertically with some loops of metal strapping.

In his estimation, this was just what he needed to keep the tree from being damaged by accidental equipment bumps – the boards, in effect, would suffer and the tree would be spared any battle scars.

Although I admire and respect his desire to protect the tree – something that far too many construction firms neglect – my suspicion is that he accomplished nothing by dressing the tree in this hoop skirt. Indeed, while the photographs that accompanied the article were meant to show his trunk protector in action, it was clear that the tree was headed for an early demise, as the new home had been positioned just a few feet from the trunk.

I’m not a seer and cannot predict what will happen two, three or five years down the line, but experience tells me that this tree will not be with us in 2013 and may not last even that long.

STEERING CLEAR

All of us at one time or another run up against trees that are very much in the way – and our clients simply won’t let us remove them. To be sure, working around such prized specimens can be a real pain, which is why so many in the construction trades have passive-aggressive attitudes about them and just wish they’d go away. Indeed, this may be why so many turn their backs when it comes to doing what it really takes to protect them.

The resentment of such trees grows by leaps and bounds when they create traffic problems on site, which might explain why their bases become such great resting places for pallets of concrete, unused equipment, scaffolding and garbage dumpsters, among other things. In actuality, the weight of these objects does more irreparable harm to trees than the occasional ding with a backhoe bucket or skid-steer loader ever could.

The plain fact is that not only do we need to protect the trunks, but we also need to keep equipment and materials far from the trees’ roots as well. While trees scarred by encounters with equipment show their injuries in an obvious way, the injuries created by root compaction and damage are not so immediately obvious – nor do the consequences manifest themselves right away.

I would need a calculator to tally up the number of times I’ve been called to clients’ homes through the past 30 years to answer the same question: “Why is my tree dying?” In most of these cases, the clients paid a premium price for a “wooded” lot only to be left without a single thriving tree even five years later. The main culprits? Root compaction, root damage and changed grades.

In my consulting work for the town of Penfield, N.Y., I spend a substantial amount of time walking around potential building sites to evaluate vegetation, particularly the trees. I review grading plans presented by the developers’ engineering firms to see where cuts and fills will be executed, and I also check for utility and roadway placements.

Once my surveys are complete, I make recommendations as to how particular trees or groupings of trees might be saved, either by changing or removing some building lots, repositioning roadways or making any number of other changes. I do so for a simple reason: You cannot cut a roadway within the drip lines of trees and expect them to survive. Nor can you install storm sewers or raise the grade by several feet in the close proximity to those trees without doing them dramatic harm.

Trees and their surroundings must remain undisturbed at least to their drip lines (that is, to the full extents of their canopies of branches and leaves). The running of equipment within those lines and over the roots is a sure-fire ticket to those trees’ slow deaths: Compaction of the soil blocks the roots’ ability to exchange air, water and nutrients with the surrounding soil and slowly (but surely) suffocates them.

CREATING A PERIMETER

Part of the problem is that, when faced with mistreatment, trees don’t immediately shrivel up and die. It can take months for the first signs of distress to materialize – branches dying back, increased susceptibility to diseases and insect infiltrations, leaf loss and more – and sometimes years for trees to die completely.

Gradually, however, dead growth shows no signs of regenerating; branches break off in storms and fall to the ground (or onto houses, cars or homeowners!); and such trees are eventually beyond recovery. Finally, they must be removed before they become even more menacing.

This, to make a long story short, is why it’s absolutely imperative that trees must be protected on job sites.

| Although it was clearly someone’s intention to put up some kind of protective barrier around this tree, it didn’t happen soon enough to keep a couple pieces of equipment from finding resting places well within the tree’s drip line. It’s a situation that can harm the tree — but the damage likely won’t manifest itself until long after the consruction crew has left the site behind. |

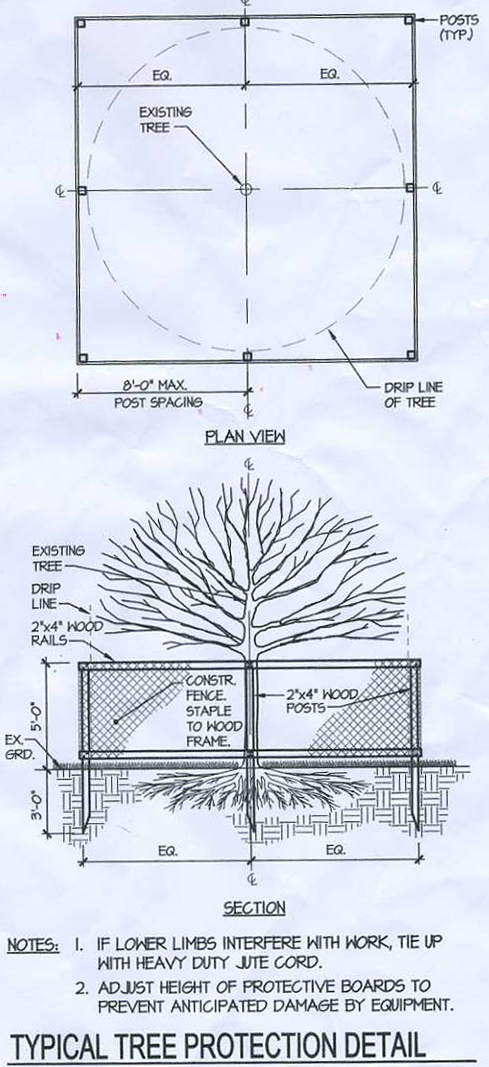

By protection, I mean that trees must be given wide berth by all equipment, people and materials, typically by installing fences around them that extend to their drip lines. The simplest and least costly way to do this is to install snow-fence stakes to create perimeters and use orange construction mesh to block access to the protected areas. It’s that simple.

It’s also inexpensive: By his estimation, the builder mentioned at the outset of this column spent about $250 (in time, materials and labor) in wrapping his tree in lumber and probably ended up killing the tree anyway by damaging the roots in setting the home’s foundation – although he’ll be long gone and off to another job site long before that happens. By contrast, stake-and-mesh systems cost very little and are a good way to save trees. Indeed, builders will never need to give the trees’ safety a second thought.

To be sure, there are situations in which maneuvering close to trees is inevitable. If there’s truly no alternative to driving over root systems, then a fairly effective way to protect them is to pile at least eight to 10 inches of nursery mulch throughout their drip-line zones, thereby distributing any load and minimizing the damage to be done by equipment.

If you use this approach, you must avoid turning the equipment (especially skid-steer loaders) within the drip-line zones: This will dig the tires or treads into the mulch and apply pressure to the ground below. And remember: It’s equally important to remove the mulch at the end of the project.

At that time, if it’s apparent that, despite your best efforts, some compaction has occurred, it is essential to bring in an air-infiltration gun to aerate the soil around the tree and break it up a bit.

MAKING THE GRADE

Beyond the instances highlighted above in which root damage and/or compaction played leading roles, an equally difficult time for trees results from projects that involve changing the grade in their vicinities. Quite often, in fact, new development inevitably means changed grades.

Through the years, I’ve advised many developers on ways they can alter their plans to avoid grade-change issues and protect stands of mature trees, and almost universally the response is: “We can’t do that.” The reason they usually give is financial, and they seem immune to my counterargument that a wooded site is more valuable than a non-wooded one and they might thereby recoup their costs many times over. Make sense to me, but doesn’t seem to influence their thinking at all.

In a recent situation that I was involved with, for example, the developer presented a plan for a site where he’d bought three houses in a row and planned to knock them down and replace them with four cookie-cutter commercial buildings. The lots had originally been residential and had some trees that had been cared for by the homeowners, including a 30-inch sugar maple, a number of oaks in the 24-inch range and a large stand of pines.

In a recent situation that I was involved with, for example, the developer presented a plan for a site where he’d bought three houses in a row and planned to knock them down and replace them with four cookie-cutter commercial buildings. The lots had originally been residential and had some trees that had been cared for by the homeowners, including a 30-inch sugar maple, a number of oaks in the 24-inch range and a large stand of pines.

|

Protecting trees is simply a matter of defining a boundary at or beyond the drip line and putting up a rudimentary barrier to prevent random misuse of the space. |

As presented, the plan called for stripping the site and laying out the four buildings on a rigid grid with more-than-ample parking areas all around. I walked the site, then went back to my office and rearranged the footprints to preserve the largest of the trees and the stand of pines. What I suggested in no way diminished the total square footage of the buildings and preserved 85 percent of the parking spaces.

I saw the pines as creating a picnic area for employees of the future businesses that would occupy the buildings and suggested establishing a village-like appearance rather than the all-too-common strip-mall look the developer had planned. I presented my ideas to the developer and the town’s engineer (whom I answer to), and the first words out of the developer’s mouth were, “We can’t do that.”

His reasoning was simple: He told us that he needed to cut and fill areas to make the drainage system work and that the trees were in the way. I countered with my point that trees would make the site more valuable and that he could more than offset the cost of saving them – and went on to explain that all he needed to do was build wells around the trees before grading to his heart’s content.

Building wells of this type is relatively simple: You just build circular retaining walls about eight feet out from the trees to keep the bases of their trunks from being buried; beyond the wall, you cover the rest of the drip-line zones with crushed stone into which you’ve set vertical pieces of four-inch PVC pipe at intervals about eight feet apart around the tree, spanning the distance from the new grade to the original one. This is sufficient to keep the tree healthy and protect it from root damage as well.

ENCIRCLING A SOLUTION

In the plan I redrew, I used these wells to save all of the trees. I also set up traffic patterns so there would be no traffic within the drip lines – and even if there were, the crushed stone would prevent the roots from being damaged by compaction and the piping would allow for air infiltration.

I explained all of this to the developer; he said he’d discuss it with his partners and engineer and get back to us. The conversations continued and I held out some hope, but I made the mistake of going on a short vacation: With me out of sight and perhaps out of mind, the developer swung into action and leveled the site. I was shocked to drive by a few days after my return to find nothing more than a ten-acre patch of dirt.

This was a bad outcome from my perspective, because enhancing the property was possible at a relatively small expense that might easily have been recouped as a result of the site’s enhanced aesthetics and greater visual appeal. The troubling thing is, this sort of retrograde thinking happens all the time in places all over the country.

There are other issues, of course, and other possible solutions. Not all sites, for example, have areas that need to be filled. In fact, some need to be cut to create proper grades for drainage and effective use.

In such cases, I suggest staying away from desirable trees to their drip lines and leaving them alone on plateaus. Alternatively – and if planning time allows – it is possible to start a year or so before construction begins at gradually root-pruning trees back toward their trunks to promote root development in tighter circles. This is a program that requires the expertise of a certified arborist who knows the proper techniques and will be on hand through the entire process to monitor the trees’ health.

I started out this discussion with a desire to impart some simple advice on protecting trees on construction sites, and I’ve done so to the best of my ability. But I’m not an arborist, and I know well enough that if I have any doubts about how to handle trees put at risk by my actions on site, it’s time to call in a professional and get his or her recommendations on how best to proceed.

At that point, it’s my responsibility to make certain everyone on site follows the program that’s been established: It’s the best way I know of to keep trees safe – and the best way to preserve the value that trees add to the properties we’re called on to enhance.

Bruce Zaretsky is president of Zaretsky and Associates, a landscape design/construction/consultation company in Rochester, N.Y. Nationally recognized for creative and inspiring residential landscapes, he also works with healthcare facilities, nursing homes and local municipalities in conceiving and installing healing and meditation gardens. You can reach him at [email protected].