Great Lengths

Of all the sports, there’s none that relies more on the art of landscaping than golf. The contours of the land, the style, size and placement of plantings, the use of elaborate stonework and the installation of substantial bodies of water often define not only the competitive challenge of the game but the ambiance and character of the entire golfing experience.

This is especially true of championship golf courses, where designers seek ways to stretch the envelope in terms of the way the game is played and in the physical beauty of the courses themselves. In their search for true distinction, many have turned to the use of carefully designed and installed watershapes, both as water hazards and aesthetic accents. Indeed, even a quick survey of courses built in the past 20 years reveals that water has become an emblem of the modern game.

Building these bodies of water for top-flight golf courses is a unique challenge: Success requires working hard to make everything look as natural as possible on a very large scale – and making sure that golfers wearing spikes don’t poke holes in your work as they play.

POINT OF DEPARTURE

At Pinnacle Design Co., our goal is to create natural watershapes and landscape environments on golf courses to complement and extend the vision of the developer and the golf-course architect. In most cases, that means building watershapes and landscapes that look as though they’ve been there forever and that the links just happened to have been cut around them.

These are extremely large projects by most anyone’s reckoning. A typical championship golf course may include 60 to 100 acres of landscaping, while streams may measure a mile or more in total length and ponds or small lakes can be sized in terms of acres of surface area and hold millions of gallons of water.

|

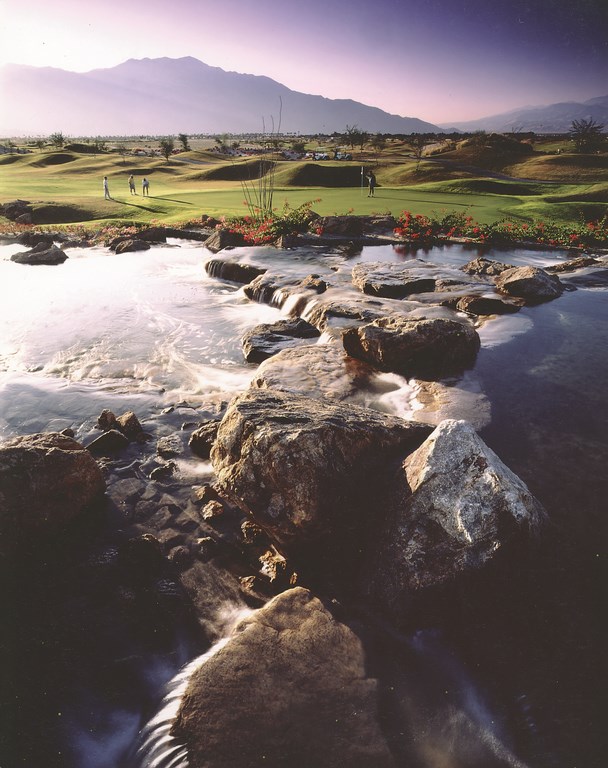

In a Rock Quarry An example of a bold watershape that really hit the mark is “The Quarry at La Quinta.” It begins as the backdrop of the tenth green at the La Quinta Country Club near Palm Springs, Calif., and then cascades into a series of ponds and streams along the entire right-hand side of the golf hole. Everything you see here is manmade: We imported 2,200 tons of boulders and cobbles for the streambeds. The waterfall was built using highly detailed artificial rock. By using boulders of a type that matched those found in the existing terrain and by making use of distant views, we were able to create the illusion of this rocky stream in the middle of the desert. The sloping, rocky banks and carefully random dispersion of small and large rocks in the streambed all work to give the impression that the stream is natural. Interestingly, a massive alluvial fan drains into the course, and we had a situation where a 100-year storm could advance a wall of water five feet high by fifty feet across. The civil engineers working on the site decided that we needed a concrete structure that would protect the golf course from flooding – hence the size and location, which provides the transitions for the waterfalls in the stream while serving as that structure. (Photo at left by Tom Brewster, at right by Frank Domin) |

The mechanical and material ends of things are outsized, too. Plumbing ranges from six to 24 inches in diameter, while the three-phase pumps we use run from ten to 150 horsepower. And on a typical job, we may use as much as 2,500 tons of natural rock and tens of thousands of plants and trees in dozens of species.

Adding to the challenge is that no two courses are alike – nor are their designers and owners. Bringing practical realities into alignment with a designer’s or developer’s vision can be a bracing at times, as can making everything work within ever-increasing environmental constraints. But through careful planning, competent construction and constant site supervision, we bring it all together.

In doing so, we have a simple touchstone: Given the overall design, we draw our primary inspiration from the site. From stone and plant selection to contouring the earthen substructures for streams and waterfalls, it’s the site that dictates what will look natural and what won’t.

As with so many collaborative efforts, however, this is all easier said than done. During the design phase, we’re given a site plan that shows spaces and corridors set aside for the water elements and landscaped areas. From that point on, we work closely with the architect and owner, but we know that how we establish the watershapes and put our mark on them with respect to shape, elevations, flow rates, construction details and basic presentation will make all the difference in whether or not the water looks like it belongs there.

To be sure, this is something that works out more easily in some jobs than it does in others. When a project includes dramatic elevation changes, existing water and indigenous stone – and the available palette of plants affords us lots of choices – it’s not all that difficult to bring interest, balance and variety to the site. On the flat, however, the challenge rises as we introduce elevation changes and use more subtle effects in the watershapes – making it all look beautiful without seeming completely out of place.

THE FUNDAMENTALS

The feature of our business that lets us succeed in an environment where, first, there’s usually a basic plan we didn’t have a hand in developing and, second, there’s a site that’s fundamentally different from the courses we’ve worked on before, is the fact that we use a consistent method in the design phase, boiling everything down to three keys:

[ ] Basic appearance: What should the water look like? Do we want a meandering stream? Crashing whitewater? Do we want it to look as if it’s moving through a marsh area or over boulders and cobbles? How will what we’re thinking about doing fit within the context of the site? How believable is the system going to be?

[ ] Basic role: At what points in the architect’s plan does water exist to present a hazard to golfers? At what points does it retire into the background and exist strictly for beauty’s sake? Have we considered all of the relevant focal points so that golfers can see the water and play over or around it accordingly? Have we accommodated the fact that water hazards are usually broad areas of still water that can be seen from key areas of play such as tees, landing areas and greens?

[ ] Basic environment: Are we considering selection and placement of materials and formation of edges that are both beautiful and believable? Are we after a rocky stream, or is it going to have earthen banks with signs of natural erosion? What plantings will work best in these situations? What materials can we borrow from the surrounding environment? What do we need to import?

We spend a tremendous amount of time in the planning phase considering these questions, the principles behind them, the course architect’s ideas and, especially, the site.

We do so because we know the decisions we make here will have a huge impact on what happens to the physical structures in an around the proposed watershapes. If, for example, we have course topography that includes significant hills with drainage channels entering the golf course, this may provide us with an opportunity to define bigger, more cascading types of streams. The site determines whether such a watershape works and belongs there.

By contrast, if we have a relatively flat site – in a desert, say – and the natural surroundings show us that there isn’t going to be much water present, then we’ll approach things differently. Here we might go for slow, meandering streams, or narrower streams. Or we might think in terms of Japanese gardens and set things up so that water appears and disappears as you move through the environment. Or we might go bold, using flat bodies of water contrasting sharply with expanses of turf or the starkness of a desert setting.

Every step of the way, of course, we interact and consult with the developer, golf-course architect and hydraulic engineer to be sure that our own design ideas flow in with those of all the project’s major players.

WORKING TO SCALE

Not much of what I’ve written so far is different from any substantial watershaping project: the need to let the site guide you in your approach, the need to coordinate with others participating in the project and the need to answer questions related to appearance, intended use and basic environment.

The first real distinction I see is the matter of scale.

Long before the earth-moving equipment moves in, we do lots of on-site surveying to measure and confirm the placement of our watershapes. If we spot problems, we bring them to the attention of the architect and the development team. Once everything is resolved, we bring in a team of contractors whom we know from past experience will get the job done.

The large scale dictates a higher-than-usual degree of coordination, and no matter how well we’ve designed and prepared for the project, we are only as good as the performance of the contractors doing the work. The key to overseeing and ensuring superior performance and a top-notch outcome is due diligence prior to selection of the contractor. That’s why working with contractors we know is essential.

Another scale-related distinction is that we work to integrate multiple watershapes into an overall system. Most of the courses we work on have a large lake that serves as an irrigation reservoir. We’ll look for ways to combine our major streams with the reservoir so that, as water is drawn off for irrigation and is replaced, the water in the stream is also replaced. These streams help maintain the water quality by providing vital aeration to the water as it tumbles over rocks and boulders.

Once the pieces all come together, these water systems are relatively simple in function. We typically don’t use filtration (when we do, it’s a large bio-filter in the bottom of a lake), and generally we have just single points of suction and return in the system.

There’s no really skimming to speak of: In some lakes, the maintenance staff will manually remove material from the surface if it becomes excessive, but leaves and other surface material usually are left to sink and become part of the biomass at the bottom of the lake.

FIELD SUPERVISION

Another distinction that comes with working at this scale is the simple extent of the shaping and finishing work to be done over dozens of acres. Indeed, after the golf holes have been graded and the lay of the land has firmly been established, we’ll spend a good share of our time in the field locating basic stream courses and the sizes and shapes of ponds and lakes.

By and large, once the overall, mass grading is complete, we know pretty well where the water is going and what it’s going to look like. Now we move to the site itself and begin to worry the details. We start by over-excavating the streams and lake edges before contouring the primary earthen substructures to the desired shapes. We spend hour after hour with the shaper, painstakingly creating the sub-grades that will enable the stream to look natural. (The over-excavation provides us with ample space to backfill over the edges, hiding all the necessary manmade structures such as the liner and concrete that will come later.)

This process sets us up to build distinctive structures within the streams themselves, including cascades, deep pockets where the water pools, or eddies around rock outcroppings. We create depressions where large boulder and rock structures can be placed without giving the appearance that everything has been stacked on the surface. We also set up shallow areas where slow-moving water will meander through grasses – and golfers might even try to make a shot from a miserably wet lie.

Every watershape we set up on a golf course has a minimum 20-mil PVC liner. The liner is used to ensure that the water – an expensive commodity on most sites – does not escape the confines of the streams and lakes.

Beneath the liner, we’ll use a filter fabric on a rocky site to protect the PVC from damage from below (although if we’ve done a good job with our grading that’s not usually an issue). The thing we do next that truly distinguishes what we do from regular stream- or pondcraft is that we top the liner with a three-inch layer of chicken-wire-reinforced concrete, thereby protecting the PVC from UV degradation, animal intrusions – and golfers traipsing into the water with their spikes. (We apply this coating only to the edges of lakes; the rest of the lake will receive at least one foot of soil over the liner.)

On top of the concrete, we pour what we call a “rock spoil,” a mixture of rock material ranging from sand up to 3/4-inch rocks with a small percentage of rocks ranging from one to six inches. This coalesces as a sort of aggregate surface that looks very natural. Then, in predetermined areas we call “bog plantings,” we apply a layer of soil into which we plant a variety of plants, from grasses in extremely shallow areas to lilies in slightly deeper areas.

REACHING FOR NATURALISM

With the liners and concrete in place, we turn our attention to details of rock and plant placement. This is the point in the project where working on site and closely supervising the work crews is essential. And of course, we do more than monitor: A great deal of hands-on creativity comes into play when we’re out in the field adjusting rocks and plants.

Rock placement in particular starts to become somewhat like playing chess. On the edges, we work hard to blur the boundary between the banks and the water. We’ll vary the size and placement of rock material so there’s a random, non-linear look. In the water, placement of rocks in the streambeds is extremely important as we vary sizes and shapes and create bends, various cascades and waterfalls. We work carefully to establish areas where water slows down and speeds up. We also use flat weirs and cascading areas to vary the sound and appearance of the water.

|

Building Bridges The Bridges Golf Course in Rancho Santa Fe, Calif., is an example of a crashing, whitewater stream – a fast-flowing, exciting watercourse for both the golf course and adjacent residences. We had quite an elevation change to work with, which again let us introduce lots of variety in a compact space. There are some areas where the water is rolling, some where there are dramatic drops, and others where it’s cascading. Never monotonous, a project like this one shows how you can manipulate the water speed and movement to create different effects and lines of flow within the banks. |

As designers, we study nature and spend lots of time observing the way streams move and the manner in which material is distributed in a natural watercourse. Nature is always full of surprises, and we try to make all of our streams look as natural as possible by varying the way the water moves and interacts with the rocks.

The rock material we use is site specific. In many cases, the area in which we’re working has been heavily excavated, not just for the golf course but also for adjacent residential properties. Whenever possible, we’ll take advantage of indigenous material to keep the cost of transporting down and also to give our rockwork the air of authenticity. If the need arises, of course, we won’t hesitate to truck in hundreds or even thousands of tons of rock. When we do so, we take our time to select material that “looks” like it belongs.

There are also situations where we deliberately reveal the hand of man. If, for example, a slope requires a retaining structure, we may go with a stacked rock look that gives the impression that it was necessary to stabilize a bank in order to work with and around existing lakes or streams. We’ve also worked in some cases with structures such as stone bridges and various types of pathways built by other contractors. Here we may use repetitive stone elements that help blend the watershapes with the obviously manmade elements.

As I said above, every job is different and for all of our careful planning, we’ve learned that there are no “rules” to govern what we do.

TO THE LINKS

When the rocks and plantings are in place, we find that we’re usually about 90 percent of the way toward completion. Now we settle in for a significant period of on-site adjustment – especially after the water’s been added and we get to see just how all of our planning and field direction has panned out.

Often we’ll find the action of the water will create erosion patterns that we didn’t even think about; in some cases, we need to change courses in one area to avoid damaging another. We also work with the edges, making sure that everything looks as natural as possible and, more important, that the watercourses are not leaking outside their lined banks.

The final distinction in what we do when compared to most watershapers is the amount of time we spend in planning the aesthetics – and in following through to make sure everything’s in place. Nothing is more satisfying at the end of the day than to sit back with the sense that what we’ve done truly belongs where we put it. The ultimate validation comes when golfers can’t distinguish landscaping and water that was existing from that which was manmade.

And that’s an important quality, because there are far too many golf courses that don’t project an air of belonging. They just seem out of place. In our work, however, we do all we can to bring artful landscaping sensibilities to the work and create environments that are as much works of art as they are places where duffers shout “fore” and handicaps are either improved or forgotten.

Ken Alperstein is co-founder of Pinnacle Design, a golf-course architecture firm with offices in Palm Desert and San Diego, Calif. He is a 15-year veteran of the landscape design industry and has specialized in golf course landscaping since 1989. Alperstein and his partners, Ron Gregory and Bill Kortsch, founded Pinnacle to serve the highly specialized golf course design industry. The company’s portfolio includes high-end championship golf courses, clubhouses and grounds throughout in Western United States – including several courses rated in the top 100 in the United States by Golf Digest and Golf magazines.