Glassy Permutations

Glass tile has long been one of, if not the, most distinctive material used in swimming pools. Applying the science of optical physics, inventor David Knox of Lightstreams Glass Tile, takes on projects that require one-of-a-kind tile creations for designers and clients that want something no one else has.

By David Knox

Creating glass tile that is project specific – i.e., custom-made for a single client – is both a great opportunity and at times a tall challenge. It’s almost always a chance to stretch creatively and technically, and almost always big-time fun, the part where I can really think and create in terms of a specific, more personal environment for the client without considering as much, universal appeal.

There are many other tile suppliers that create custom-blended mosaics out of their existing tile product lines with gradations and mixes of color, and there are also companies that create custom ceramic tiles for specific customers. While we almost daily create custom mixes of different glasses and different patterns, at Lightstreams Glass Tile, I’ve always taken it one step further. In those situations that warrant the effort, we create entirely new tile designs with new colors, textures, optical effects and sizes. It’s almost like weaving a new fabric and sewing it into a new garment.

Sometimes those newly created tiles later become part of our standard product lines, sometimes they are used only once. And most of the time, for every one we end up using in the project, we have 10 or more that did not make the grade. The client rarely sees more than a few that I think are the best or that will work. Either way, it’s a modality that insinuates our work with that of the designer and the client.

These custom tiles are special and ultimately, they give everyone involved a beautiful way to distinguish their own work from the run of the mill, and the clients an opportunity to own something truly unique. For our company, we have a rich history of long-term customers that truly are bonded to us through our glass and the visual experience we created on their behalf.

ENGAGING PROCESS

When I’m contacted by a homeowner, their representative, an architect or a pool builder, I first want to gain a broad sense of what they think they want it to look like. Perhaps we’re working on a project in a mid-century modern style, which in general terms suggests some kind of a clean look. Once I have that basic direction, I step back and hold that in my mind for a small amount of time.

Next, I want to have a good look at the site. I always ask for photos and whenever possible, I’ll visit the property in person. I’ll also google information about the area to gain a general feel for the environment. If, for example, the property is in a forest area, that can lead to very different ideas than if it’s located in the desert, and different still from a very urban setting. .

Wherever it is, I’m striving to have the tile respond to the setting, whether that means blending in with it, or possibly offering some kind of contrast, although I never want to clash with the surroundings. Glass can look very artificial when it’s in the wrong environment, or there is too much of it or not framed well by the other materials. The glass has to both stand on it’s own as an element yet fit into the environment like an organic growth from within

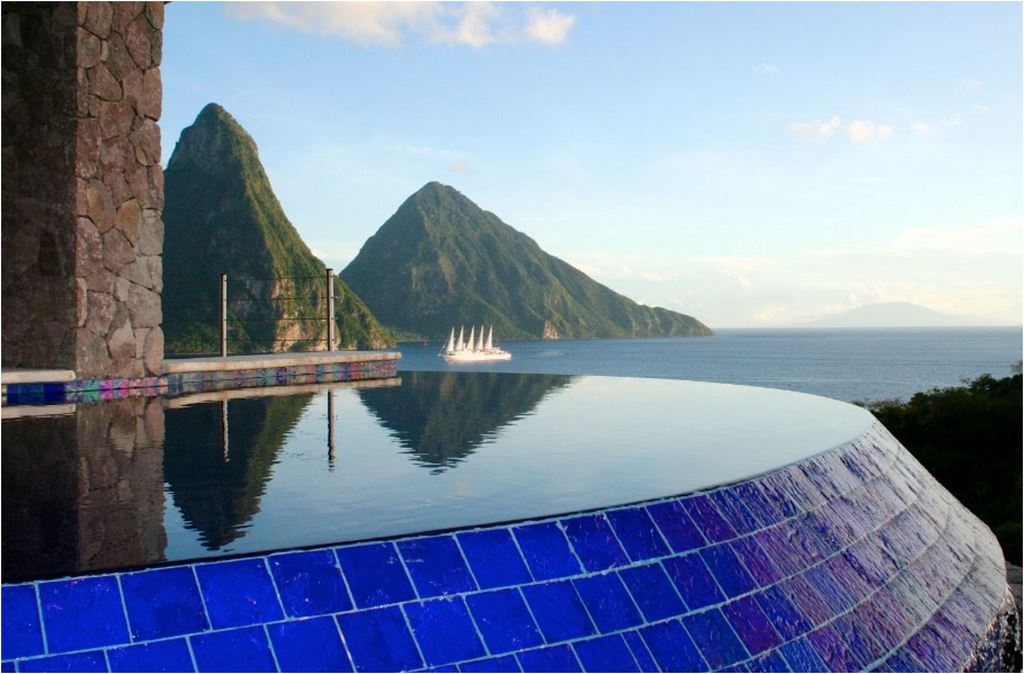

Back in the mid-2000s, I created a series of custom tiles for a now-famous project known as Jade Mountain, a highly unusual resort on St. Lucia in the Caribbean. It looks something a modern version of the Hanging Gardens of Babylon with rooms, or sanctuaries as they call them, that each feature a differently colored vanishing edge pool.

From a design-development standpoint, it was a huge undertaking and I spent a lot of time there gaining a detailed understanding of the place, especially the colors. The structure was a massive labyrinth of stone, coral tiles and beautiful hardwoods that was growing right out of the mountain and flora- but bland. My task was to create the color and make it fit with the stone. But I also wanted it to be alive and moving with the sun and water, changing constantly with each moment.

We wound up creating 26 different tiles all in carefully crafted colors, many of which we never used anywhere else, although a few we did continue are part of our product line. One of the colors we never used again was a very Grandma rose color I developed that fit in with many of the flowers there, but it was so unusual as a glass tile color it was hard to imagine it working very many other places. Another was an Avocado green that was actually the first batch we sent. I held my breath thinking they might cancel the contract after seeing it yet to my surprise- it looked fabulous in the midst of that tropical environment and they loved it.

We also created tiles that blended with the colors of the ocean, a texture that complemented the stone material used in the building; beautiful reds, root beers, and ambers blending the tropical hardwoods used in the architecture and furniture, the sunsets and especially the lush greenery of the mountainous terrain. To date, that is the most complex and extensive project we’ve done, and more than 15 years later, the all-tiled pools and bathroom still look perfect. That said, we have since developed hundreds of designs and I think the most recent project was one of our best glasses ever.

When looking at the environment, I’m always trying to figure out how the tile will visually function in the setting, whether it’s a subtle look or something that makes a bolder statement. At Jade Mountain, the colors are bold because the setting practically explodes with color. Soft earth tones wouldn’t have worked there, while in other places, the vivid colors would look out of place. It all depends on the setting.

MAKING IT

This conceptual period usually involves varying degrees of interaction with the clients or their representatives and as is true of all design challenges, client input and subsequent buy-in to the direction is essential. I focus much more on what the client wants it to feel like or what feeling it gives them much more than what they kind of blandly may want it to look like.

Once we have established the color, along with other key factors I’ll discuss below, then it’s time figure out how we’re going to make it in the factory. Without going into manufacturing details, I developed a method of making glass tile that combines various elements that I can use in seemingly infinite variations.

When I’m formulating the new tile, I’m not only thinking about the end product but how to get there so the product is not overly expensive, and so that we can do logistically within our own operation, which does have limited manufacturing equipment and labor force. I can come up with all sorts of designs but actually making them is different challenge.

It can take some extremely focused mental effort, but I find that nuts and bolts manufacturing side of it a stimulating exercise, because it’s so directly tied to the artistic side of the equation. They go hand in hand, which is why I consider our operation a kind of studio-cum-manufacturing facility.

During this manufacturing-design phase, I work very closely with my material suppliers who make the glass we use and others who provide the various reflective raw materials that give our tile such a distinctive appearance. We use only the best art-grade glasses in any of our melts so while it presents some limits, it gives us the advantage of knowing that the mechanical outcome is going to be superlative.

I specify what we need and in what quantities, which enables my suppliers to tell me what it will cost. That’s where the financial practicalities come into play. There is also the labor issue: I find it exceptionally interesting to create designs that can be made in production by everyone in the factory. Despite the variables and having each and every tile unique (400k in a recent example), by creating a cookbook and a methodology, it does not require my constant input. In fact, I like the idea of setting it all up and letting heat, gravity and our fine staff do the rest. What comes out is beautiful and everyone played a part in it.

Producing custom, project-specific glass tile is an involved process. It’s costly both in terms of dollars and cents, and in terms of the synapses you have to deploy to figure it all out. As I mentioned earlier, it also usually requires a number of experiments and design failures. That’s why I won’t do this unless it’s over a certain volume of tile. I won’t go into specifics, but it’s fair to say that 1,000 square feet is well short and I need to at least have some confidence that the client is serious and likes what we make in our standard products.

Another aspect of the designing the manufacturing process involves tapping into work I’ve done before. I’ve been affectionately described as something of a mad scientist. It’s true in the sense that I always have experiments going and I’m surrounded by the different end results. There is a wealth of knowledge and probably some forgotten beauty in the ones that gone tossed into the experiment bins.

I may or may not ever actually sell some of these iterations, but there always there to remind of the various ways I can approach the manufacturing process and that’s particularly useful in these types of projects that require creative thinking both artistically and technically. In some situations, I can make the tile we need simply by tweaking a design from the past. For other projects, it’s a start-from-scratch proposition. In one project, I ended up sending the architect over 25 different samples and I just almost predictably, they came back and chose the very first one I sent.

THE INFINITE FIELD

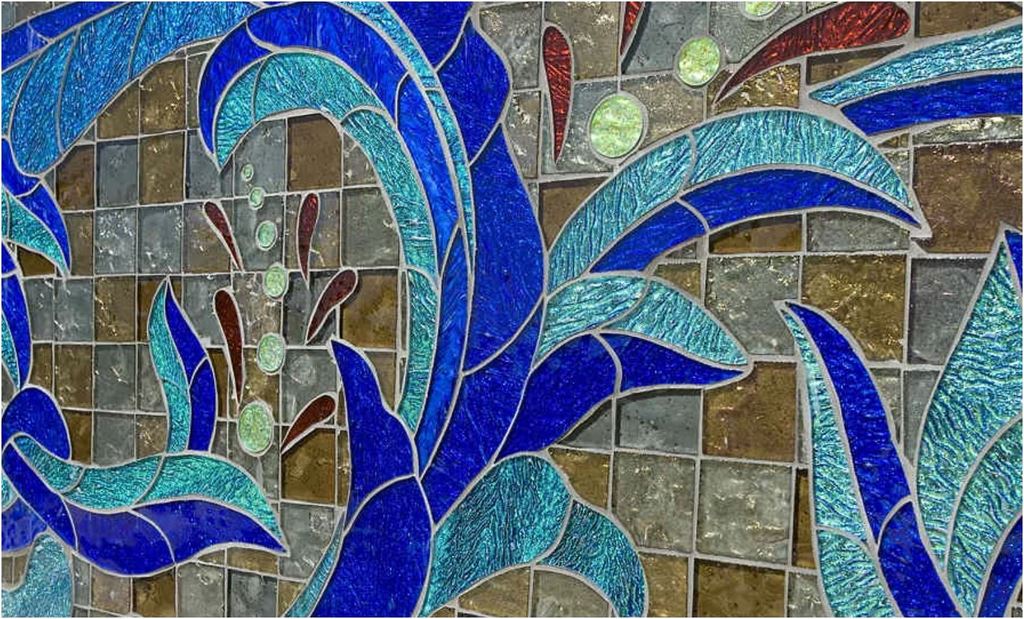

This entire process is a matter of considering the macro and micro perspectives. The close view and the broader perspective work together to create what I call the “infinite field,” which refers to the shifting visual dynamics you can achieve by manipulating color, opacity, texture and size of the tile.

Color is probably the first thing most people think of when considering the type of tile and look they’re trying to achieve. Anyone who has taken a close look at our products knows that the colors are complex because they are a combination, a mosaic, that exist within each individual piece.

The color palette starts with a background color, just like it does with a traditional mosaic, or an image rendered in needlepoint or a stained-glass window.

When viewed up close, it’s easy to see how the elements within the tile interact and how each piece is slightly different, like snowflakes in that sense. Then when you step back and look at it as a visual field, the composite color becomes apparent. By manipulating the color of the glass, the background color and the iridescent materials, I’m able to achieve a vast spectrum of colors.

Translucence, the light that penetrates the glass surface, enables this interplay of base and iridescent colors to interact to create varying prismatic effects. There’s visual depth to the tiles that results in this ever-shifting optical field. It changes as the angle of the sun moves throughout the day, and it changes as you move around the tile and view it from different angles relative to the light source.

It enables people to experience light in a way that they would only otherwise experience by looking through a kaleidoscope, stained-glass window or an actual prism. Sometimes very subtle and static; sometimes vibrant.

TACTILE APPEAL

Texture is also extremely important to creating the behavior light interacting with the base and variable colors, and it effects the prismatic behavior of the light. We have tile that is “smooth as glass” as well as tiles that have subtle relief that creates even more varied visuals because we’re manipulating the contours of the surface and the surface area. From some viewing angles the surface texture is all might read, but then when you change positions relative to the light source, the texture influences the light penetrating the glass.

In addition to the work texture does with the light, it also creates a different tactile experience. I want people to want to touch our tile and then when they do, it’s enjoyable to the touch. In that way, people are drawn to the tile as you might be to a fabric when you’re shopping for clothes. In pools or showers, people come in physical contact with surface on a regular basis and the sensation of touch can be every bit as impactful as the look.

Tile size also has a significant impact on appearance and the tactile experience. Because I’m essentially making prisms, the question becomes do we want small prisms or bigger ones? We make tile in range of sizes, but I’ve avoided going as small as some other manufacturers.

When I look at ½-inch-by-1/2-inch tile mosaics, which are very popular with lots of people, there’s so much grout that to my eyes it detracts from the tile surface. Depending the size of the tile and the width of the grout, you can easily have 10-to-20%, or more, of the surface area is devoted to grout. When you go to a larger tile, say a two-by-two, you dramatically reduce the amount of grout. I also like a larger optical aperture: it gathers more light and diffuses and shifts the colors before it reflects back to the viewers eye.

It’s also to important to consider the labor involved, both the produce and to install. The smaller the tile, the more labor intensive it becomes in the installation process. Whether we’re designing tile for our product line, or a one-off project, I’m always thinking about the labor involved, because that impacts the level of difficulty, the chance for installation problems and in the end, the cost to the consumer. We once designed a glass I called Volcano which was spectacular- and realistically almost impossible to install even by the best so it founds it’s place in the archives.

BUYING IN

As I mentioned just above, the client ultimately has to approve of the tile that will be used in their project and even though their architects, pool builder or whoever is helping them make decisions will have a significant influence on the process, it’s the homeowner, or commercial client, who has to look at it over and over again on their property.

Because the tile is such a key visual element, and also because it does represent a sizable investment in pure aesthetics, I am always striving to create something the client not only buys into, but falls in love with. Ultimately, it should be a point of pride and ongoing enjoyment. If it’s not, then I don’t feel the process was entirely successful. I also want the tile to be timeless; like a beautiful, antique glass door knob for generations to come.

In practical terms, that means we might create six different tile types to find that perfect one. The builders and architects I work with almost always create large sample boards they can view in situ under different lighting conditions, and they may decide to also look at it underwater, which frankly is where things can get really interesting, because of how the optics are influenced by the way the water influences the behavior of the light reflecting from the tile.

For all of the technical rigor that goes into this process, it’s really those entirely subjective almost emotional responses that people have that tell the tale. This is a visual medium and for the work to have the maximum impact on the client, they need to see it and hopefully embrace the look we’re going to provide them. You can’t describe why it’s better, or why it has value or usually, what it even looks like. It’s an optical event, whether subtle or dramatic and only exists in the moments you experience it.

I recently completed a project for a high-end residential client in the islands which came down to some very subtle variations that wound making all the difference for the clients. It’s beautiful grey-white tile that subtly transforms at angles and in moments to a beautiful sunset or blue sky.

Almost like a spirit within the glass that comes out so often. The texture of the tile is a soft, almost satin-like feeling and appearance. The idea was that as the light plays in the water, the color and movement would diffuse and make an almost Monet-like appearance at different times. If you looked at the structure, you probably would not notice it right away and then it would catch your eye like a colorful bird in flight.

What I love about this part of the manufacturing process is that it keeps me and our entire company engaged on a level that goes far beyond looking at tile as a commodity, but an opportunity to create a unique experience for the consumer, and it does keep us coming back for more.

David Knox is president and founder of Lightstreams, a manufacturer of specialized glass tile in Mountain View, Calif, which recently became a wholly owned subsidiary of Pebble Technology. He earned bachelor’s degrees in art history and American studies from Connecticut College in 1978. Following stints on Wall Street and beyond, he established Directed Light, a laser-systems development and manufacturing firm in San Jose, Calif., and pursued additional studies in mathematics and optics. During the 1980s and ’90s, the company made lasers for a veritable “who’s who” list of major technology firms, including Hewlett Packard, Motorola, Raytheon and Hughes Aircraft. He sold the firm in 1998 and continued to consult for the laser industry until 2002, when he changed career directions and began applying his knowledge of lasers and optics to the manufacture of glass tile.