Giverny: A Living Masterpiece

The water gardens at Giverny have inspired visitors since the turn of the 20th Century. Home to Impressionist master, Claude Monet, the legendary landscape has been the subject of countless paintings and photographs, not only by Monet, but numerous artists famous and obscure—and it features what is arguably the world’s most famous pond.

By Meena Dandridge

I first visited Giverny, France, while traveling through France in the summer of my junior year at college. The Gardens and home of Claude Monet were the highlight of what was a life-changing adventure.

I was there on a beautifully sunny day in early May, when the flowers were bursting with brazen colors. Not knowing anything about landscape design or the plant kingdom, I was nonetheless vastly inspired by the complex garden spaces, and when I saw how they influenced some of Monet’s greatest works, my interest was locked in for life.

I’ve returned three times in the decades since, and have relived that initial feeling of jubilation, inspiration and fascination with each visit. It is truly one of the most beautiful spaces ever made by human hands, perhaps rivaled only by the greatest Japanese gardens upon which Giverny is based, and a few others scattered around the world.

For my part, Giverny stands alone with the combination of its sheer beauty and vast artistic influence.

BEAUTIFUL IMPRESSIONS

To understand the garden is to first encounter the artist who created it.

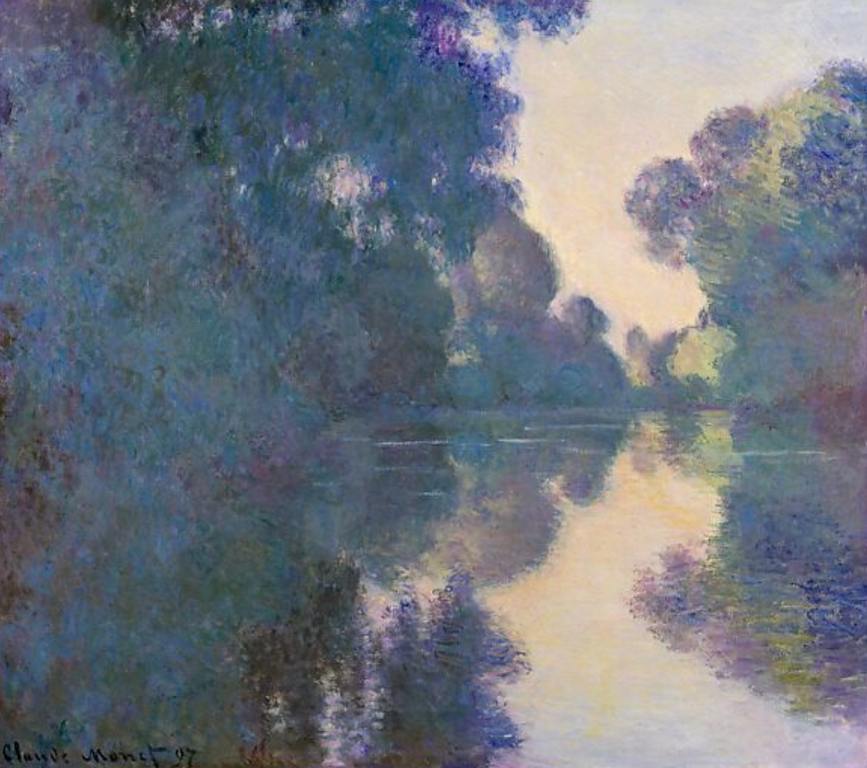

Monet (1840–1926) was a revolutionary French painter whose pioneering work in Impressionism forever changed the course of art history. Best known for his luminous landscapes, serene water lilies, and masterful use of color and light, often painted in his sprawling gardens. Monet sought to capture the fleeting beauty of nature with unmatched sensitivity and artistic prowess. His career spanned more than six decades, very much an international star in his time.

Monet’s water garden at Giverny is a seamless blend of art and nature, where water, light, and flora create an ever-changing impressionist masterpiece. It is truly a place where life meets art. You feel like you’re walking into a painting, which in a sense, you are. It is both the inspiration for Monet’s famous Water Lilies series, perhaps his most influential works, and a transformative space that continues to captivate visitors, artists, and landscape designers.

In 1883, Monet moved to Giverny, a small village in Normandy, where he leased a home with a large garden. Over time, he acquired more land and shaped the surrounding landscape to align with his artistic vision. In 1893, a decade after his arrival, he purchased an adjacent marshy plot of land and set out to create a Japanese-inspired water garden.

To bring this vision to life, Monet diverted a small branch of the Epte River to form the pond. Overcoming objections from local farmers who feared it might pollute their water supply, he carefully crafted the tranquil space that would become synonymous with his artistic legacy.

A LIFE OF ART

As is true of many great artists, understanding and appreciating their work is bolstered by surveying their personal history. Monet was born on November 14, 1840, in Paris, France. At the age of five, his family moved to Le Havre, a coastal town in Normandy. From an early age, Monet displayed artistic talent, particularly in drawing caricatures.

His true passion emerged when he encountered the works of landscape painter Eugène Boudin, who introduced him to painting outdoors (plein air).

Rejecting the rigid academic approach of traditional art schools, Monet enrolled in the Académie Suisse in Paris, where he met fellow young artists like Camille Pissarro. His early influences included Gustave Courbet and Johan Barthold Jongkind, both of whom emphasized naturalistic landscapes.

Monet’s artistic and commercial breakthrough came in 1874 with the first Impressionist exhibition, where he revealed Impression, Sunrise (1872)—a painting that depicted the hazy morning light over the port of Le Havre. This work, criticized for its loose brushstrokes and lack of detail, inadvertently gave the movement its name when a critic mockingly called it “Impressionism.”

STUGGLES & TRIUMPHS

During this period, Monet painted modern life in vibrant, light-filled compositions, often capturing the changing effects of light on water, sky, and landscapes. He also illustrated the fleeting moments of daily life, such as bustling Parisian streets or serene riverside scenes. And he was masterful in rendering the impact of time and atmosphere, experimenting with colors to evoke mood rather than precise details.

Monet, alongside artists like Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Edgar Degas, and Berthe Morisot, faced harsh criticism but persisted in their quest to redefine art beyond the confines of realism.

Monet endured financial hardships and personal losses in the late 1870s. His first wife, Camille Doncieux, whom he had married in 1870, died in 1879, leaving him heartbroken. However, his artistic style continued to evolve. He painted a stunning series of works in Argenteuil, capturing the shimmering waters of the Seine and the idyllic French countryside.

By the 1880s, Monet’s fortunes began to change. His works gained recognition, and collectors began to appreciate his revolutionary approach to color and light. Many art historians point to this period as the cradle of Impressionism, and arguably the beginning of the modern art era.

He moved to Giverny in 1883, a pivotal moment that shaped the rest of his career, and would have echoing impacts over the world of art far into the 20th Century.

GIVERNY & THE WATER LILIES

At Giverny, Monet transformed his home and garden into a living masterpiece, designing a lush landscape filled with Japanese bridges, weeping willows, and water lilies. It was here that he painted his most famous works—the aforementioned Water Lilies series, which he would continue until his death.

In the 1890s, Monet began exploring how light and atmosphere changed the same subject at different times of the day and year. Some of his most notable series include:

- Haystacks (1890–1891) – Capturing shifting light on stacks of harvested wheat.

- Rouen Cathedral (1892–1894) – Depicting the façade of the cathedral in varying light conditions.

- Poplars (1891) – Exploring movement and reflections in a row of trees along the river.

His obsession with light and color deepened in the early 20th century, particularly as his eyesight deteriorated due to cataracts. Despite the limitation, which some historians compare to Beethoven becoming deaf, he continued to paint monumental works, including the large-scale Water Lilies murals housed in the Musée de l’Orangerie in Paris.

CREATING A MASTERPIECE

By the time Monet began his water garden, Impressionism was already established, with Monet himself at its forefront. Giverny became Monet’s living laboratory, where he studied the interplay of water and sky, the dance of colors across the surface, and the way natural elements merged in reflection.

Rather than painting grand historical or religious themes, Monet focused on the immediacy of experience. His Water Lilies paintings, created in the last decades of his life, exemplify Impressionism’s emphasis on light, color, and emotion over rigid form.

Monet’s transformation of the landscape was an ambitious feat of engineering and artistry. The water garden was not simply a collection of plants and ponds; it was a carefully curated environment designed for artistic expression.

Monet expanded and reshaped the pond, ensuring the water’s surface was large enough to reflect the sky and surrounding foliage. By rerouting a small stream, he ensured a steady water supply while maintaining a still, mirror-like quality on the surface. Influenced by his love for Japanese prints, Monet added an arched wooden bridge, which became a central subject in many of his paintings.

Monet’s garden was designed with the same principles that guided his paintings—balance, color, and movement. His selection of plants was intentional, favoring species that would change with the seasons and create endless variations of light and texture. Key plantings include:

- Water Lilies (Nymphaea) – The stars of the garden, with varieties ranging from soft whites to deep pinks.

- Weeping Willows – Draped over the water’s edge, creating reflections and shadows.

- Wisteria – Cascading over the bridge in delicate purple clusters.

- Bamboo – A nod to Japanese aesthetics, adding height and structure.

- Iris, Azaleas, and Peonies – Framing the pond with bursts of vibrant color.

During Monet’s lifetime, the garden evolved constantly, reflecting his deep engagement with nature. However, after his death in 1926, the estate fell into disrepair. It wasn’t until the 1970s that restoration efforts began, led by Gérald van der Kemp, former curator of Versailles.

The restoration involved recovering lost plant species based on Monet’s records and paintings. The work also included rebuilding the Japanese bridge to its original design and restoring the water circulation to maintain the clarity and reflection of the pond.

Today, the garden is maintained with meticulous care to preserve Monet’s vision while adapting to modern conservation techniques.

PAINTINGS OF GIVERNY

Monet painted the water garden extensively, producing more than 250 works in the Water Lilies series. These paintings, housed in museums around the world—including the Musée de l’Orangerie in Paris and The Metropolitan Museum of Art—are considered masterpieces of abstraction and light.

His paintings often omitted the pond’s edges, creating a sense of infinite space, as if water and sky merged into one. This radical departure from traditional landscape painting laid the foundation for later movements, including Abstract Expressionism.

Each year, hundreds of thousands of visitors from around the world flock to Giverny to walk the paths Monet once tread. The garden remains a pilgrimage site for artists, photographers, and garden enthusiasts alike.

Over the years, celebrities, artists, and world leaders have visited Giverny, including painters like Joanie Mitchell and David Hockney, as well as figures such as Jackie Kennedy.

The garden continues to be a muse for photographers and plein air painters who capture its reflections and blooms in their own way.

SUSTAINING BEAUTY

In this era of climate change and environmental awareness, preserving Giverny is an ongoing effort. Today, the garden employs eco-friendly water management to reduce runoff and maintain water clarity.

It also features organic gardening techniques to minimize chemical use and preserve biodiversity. Educational programs that teach visitors about Monet’s approach to landscape design and sustainability are offered on site.

Monet’s water garden remains a source of inspiration for modern landscape architects. The space is particularly famous among designers for its use reflection as a design element, featuring a still-water surface to create a sense of depth and movement.

It also emphasizes seasonality as the variety of plantings evolves throughout the year, offering fresh perspectives in different seasons. And Monet was passionate not only about nature also incorporating cultural influences, especially Japanese aesthetics, but also demonstrating the power of blending styles.

Perhaps more than any design takeaway. Being there creates an immersive experiences where you are surrounded by a pageant of ever-changing views.

INSPIRING ARTISTS OF TOMORROW

As one of the most photographed and painted gardens in the world, Giverny will continue to inspire new generations of artists. Whether through painting, photography, or landscape design, Monet’s garden proves that water and light, when masterfully composed, can create a timeless and transformative experience.

For those seeking to design their own version of Giverny, the lessons are clear: water is not just an element of a garden—it is a medium of expression, a canvas where nature itself paints with light and reflection.

Claude Monet’s garden remains his greatest work of art—one that lives, breathes, and evolves, just as he envisioned.

CONTEMPLATING MONET

Monet’s legacy at Giverny lives on as a place of artistic pilgrimage, where nature and creativity intertwine. His words and those of his admirers capture the magic of his work and the timeless beauty of his gardens.

“Monet is only an eye, but my God, what an eye!”

— Paul Cézanne

“I perhaps owe having become a painter to flowers.”

— Claude Monet (on the influence of nature and his gardens)

“Monet’s work is the bridge between the 19th century and modern painting.”

— André Masson (French surrealist painter)

“He is the finest landscape painter of our time.”

— Gustave Geffroy (French art critic and Monet’s friend)

“No one but Monet could have painted that.”

— Camille Pissarro (on Monet’s mastery of light and atmosphere)

“His flowers and gardens are poetry. They live, breathe, and shimmer on canvas.”

— Mary Cassatt (American Impressionist painter)

“My garden is my most beautiful masterpiece.”

— Claude Monet

“Monet’s garden is not a place; it is a state of mind.”

— Henri Matisse (painter, reflecting on the serenity of Giverny)

Meena Dandridge is a writer and world traveler based in Soquel, CA.

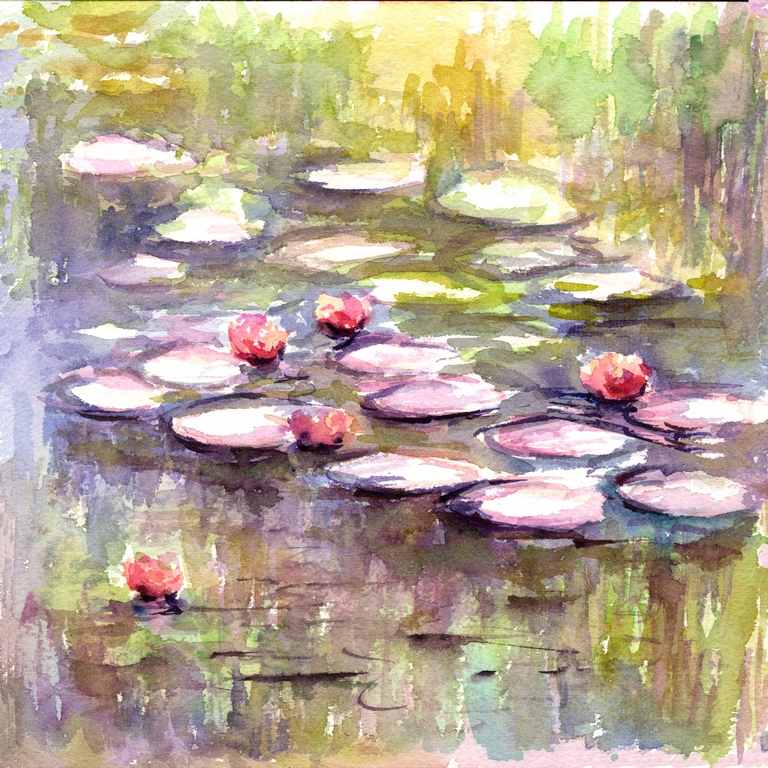

Opening photo by Julien Vitalis | Shutterstock; second image, illustration by Kunrus Nakwijitpong | Shutterstock, third image, illustration by Ann Yuni | Shutterstock, fourth image, painting by Claude Monet 1897, Morning on the Seine Near Giverny courtesy of the Everett Collection; closing image, painting by Claude Monet, 1899, Bridge over Pond of Water Lilies, courtesy of Everett Collection.

References:

- Wildenstein, Daniel. “Monet’s Years at Giverny: Beyond Impressionism.” This publication, associated with an exhibition organized by The Metropolitan Museum of Art, delves into Monet’s artistic evolution during his years in Giverny.

- Hughes, Mary. “The Design of Claude Monet’s Garden at Giverny.” This master’s thesis examines the intricate design and development of Monet’s garden, highlighting its significance in his artistic process.

- Auricchio, Laura. “Claude Monet (1840–1926).” This essay from The Metropolitan Museum of Art provides an overview of Monet’s life, with particular attention to his Giverny period and its impact on his work.

- “Claude Monet.” This entry in the Oxford Bibliographies offers a comprehensive overview of Monet’s life and work, including his time in Giverny, and provides references to further scholarly resources.

- “Claude Monet: Master of Impressionism.” This article from JSTOR discusses Monet’s contributions to Impressionism, with insights into his life in Giverny and how it influenced his art.