Sweeping Beauty

One of the things we value most in our fountain projects is that no two of them are ever the same. I can make that same statement about our custom pool projects, of course, but it’s a matter of degree: Where uniqueness from pool to pool is about selecting just the right possibilities among shapes, elevations and materials, for instance, from fountain to fountain it’s about inventing and adapting technology and pushing accepted limits to make ideas work.

The fountain under discussion in this article is a perfect illustration of that distinction. Making it happen was about figuring out how to use a single weir to move water in two directions with different flows and orientations, one part sliding gradually across a gently angled surface, the other dropping down a vertical wall. And when complete, the fountain was to be on display in a very public place: Just getting involved on this level is a great, creative stimulus.

In approaching these projects, we have the advantage of having reshaped our business, which at one time focused mainly on residential pools and landscapes, to meet certain needs we knew we could anticipate in fountain work. So in addition to the usual expertise in design, project management, construction techniques and maintenance, we also have a complete metal-fabrication shop alongside a growing facility for custom stonework.

We started in this direction to avoid falling into a creative rut. As it turns out, our path has been filled with wonderful surprises.

FINDING THE FLOW

The fountain client here was Incyte, a pharmaceutical company based in Wilmington, Del. Working with Andropogon, a Philadelphia-based landscape architecture firm, the client had expressed an interest in something that would bring a visual flash to the otherwise dull parking lot that fronted Incyte’s new headquarters building, then under construction.

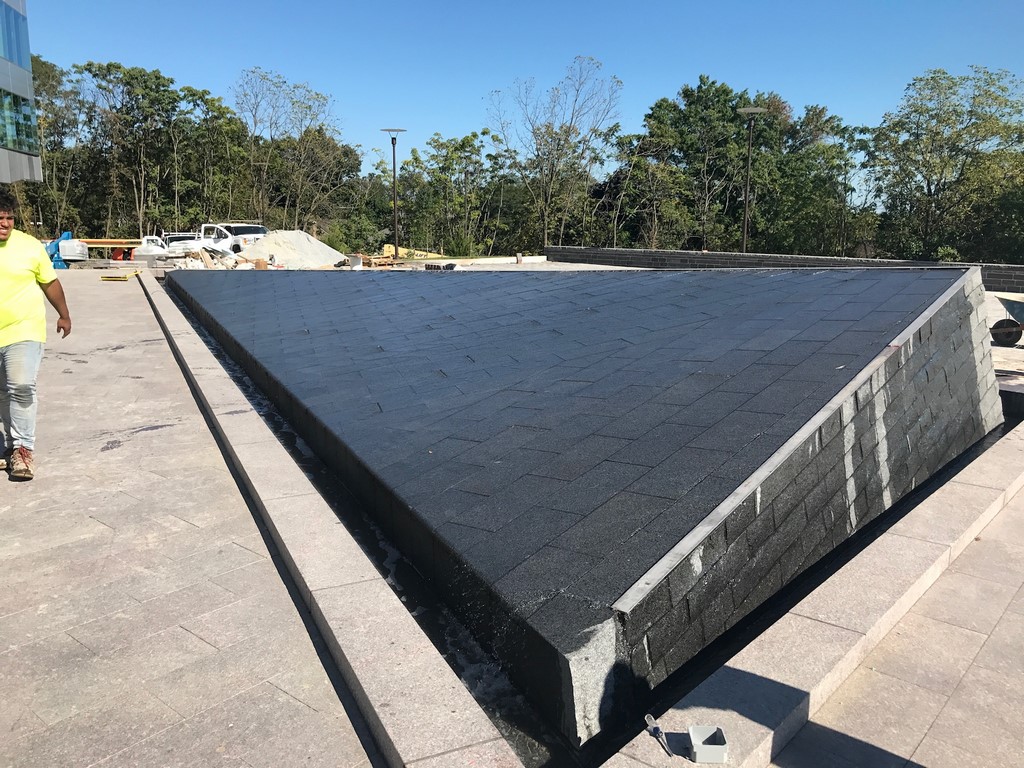

The team at Andropogon had the idea of setting up a sloping triangular waterfeature in the space and brought us in to carry it forward – which we were happy to do. But as we learned, they had a very good sense of the look they were after but no idea at all of how to make it happen.

The difference between this and similar fountains we’ve seen is that this one wasn’t just about water flowing across a broad, sloping surface. Instead, water was also to flow down the vertical surfaces on the fountain’s other two planes – a wrinkle that introduced some substantial challenges.

The issue was that the top edge of the triangular structure left us with limited real estate. It would’ve been easy to place two weirs along the top edges, one for the angled drop, the other for the vertical, but that solution was too bulky. So we needed to devise a single-weir system in which water would flow both ways out of a single fixture with an acceptably uniform flow in both directions.

It’s a good thing we had several months for tinkering in our shop before we finally started working on site!

| Our scale model was a proving ground for how the project would unfold. By the time we started working on site, we knew exactly how we’d build up the fountain structure, layer by layer. And while that was rolling along, my daughter was back in the shop cutting and welding the complex, two-way weir system we’d devised. |

Overall, the fountain is 75 feet long and nearly 27 feet wide at its widest. The highest corner is a right angle, so we needed to emit water along nearly the full length of both side segments to flow evenly across the surface to the third and longest segment, at the edge of which the water would drop into a trough that surrounds the feature on all sides.

It probably goes without saying that we needed a scale model to familiarize ourselves with the dynamics of the system we were approaching. We’ve now reached a point where we include fees for model development in almost all of our contracts: With work that involves as much speculation and experimentation as this project did, there’s really no way around this need.

So, over the course of five days, we set up a one-third scale version of the fountain in our shop and started weighing possibilities. For us, this is where the fun began as we all put our heads together to figure out a way to make the flows work. The model wasn’t perfect – no scale model really can be – but at least when we transferred our efforts to the real fountain on site, we knew more or less exactly what we’d be facing, knew the sticking points and had ideas in place to pull everything together.

MAKING THE WEIR

As mentioned above, the headquarters building was in full construction mode when we arrived on site, with countless contractors jockeying for space right where we were to be working.

The general contractor was behind schedule at the time, but still managed to make certain we had the access and breathing room we needed to insert our surge tank and mechanical systems – pipes, valves and manifolds – on a level below the parking lot before starting our work up top. In all, the system holds about 3,000 gallons, but with that much flowing surface area, evaporative losses were going to be high, so a lot of emphasis was placed on installing a capable autofill system within the 3,200-gallon surge tank.

Before long, the fountain began rising stage by stage atop the surface. Once the stone for the main triangular field arrived – courtesy of Coldspring (Cold Spring, Minn.), which worked from our detailed shop drawings and provided us with slabs and blocks cut to precise dimensions – everything fit easily, and we were ready to start working on the hydraulic details.

With the scale model, we’d worked on a free-form, trial-and-error basis; the final configurations we devised worked well, but our hasty trial fabrications weren’t ready for prime time. To make the final versions happen, I called on the talents of my 15-year-old daughter, an already-willing welder who spent her summer perfecting her skills and doing the patient, painstaking work required to perfect the weirs.

Basically, they consisted of lengths of stainless steel tubing with one corner water-jetted off (but with small sections left in place to allow the hollow tubing to retain structural integrity). She then drilled 900 holes at specified intervals on one side of the tubing to deliver water to the underside of a plate to which we mounted a V-shaped rail that had been placed to divide the flow, with one side sending more water toward the sloping surface and the other moving less down the walls.

| With the stone installed and the weir in position, we began the complicated process of adjusting the flow across the three surface planes, adjusting each ten-foot section of weir along a 100-odd-foot perimeter to ensure adequate flow in all directions and make certain that all surfaces would be wetted. After dark, we did the same sort of delicate fine-tuning with the lighting system. |

These weirs spanned nearly 100 feet in all and were divided into 10-foot sections, each one individually valved so we could finely adjust the flow all along the weir.

It had taken trial and error to develop the system in our shop, and it took lots of delicate adjusting and readjusting on site to get the visual effect we were after. When we turned the water on for the first time, we were thrilled that it worked as well as it did – then spent the next two full days taking what was 95 percent acceptable up near the 100-percent mark.

When the system is off, there’s no water visible on the surface: The trough is set on an angle that drains all the water to the surge tank. But the intention is for the fountain to run 365 days a year, despite any inclement winter weather. To make that possible, we included a large electric heater in the equipment vault to keep the water at or just above 40 degrees, come what may.

We’re particularly proud of the lighting system we built into the fountain – a run of LEDs we strung together in lengths of waterproof translucent tubing. We locked it into a slot we created in the fountain base, and it throws a warm, welcoming (and automobile-collision-preventing) glow up the fountain’s vertical surfaces. We’ve made these fixtures in our shop for some time, but we were recently cheered to discover that a lighting company has now gotten into the act, a fact that will save us a good bit of bother down the road.

A CALMING OUTCOME

In all, we were on site with the fountain for about five months, but it wasn’t what you could call continuous work. There was so much going on with building construction and with non-fountain-related exterior work that scheduling of access, material orders and deliveries was always a chain of logistical challenges. With our vertical wall stone, for example, it was part of a larger order for several project crews, and ever though our needs were relatively small, it took time for the overall order to be marshaled and processed.

Through it all, the general contractor – Baltimore, Md.-based Whiting-Turner – managed the site with skill and a determination that was something to behold. (The photographs you see here make the site look calm, but they were mostly shot on weekends when primary operations were taking a break and we had more room to maneuver.) On weekdays, the site was basically a perpetual beehive of activity, and they handled the logistics with patience and persistence. We also learned that, if push came to shove and we needed something right away, our needs were almost always accommodated.

| The finished composition meets the client’s needs fully and precisely, bringing sound and a strong visual presence to an otherwise entirely utilitarian parking lot while conjuring unique thematic support for the company’s messages about its energy, attitude and ambition. All in all, pretty cool. |

We at Outerspaces (Glen Mills, Pa.) have years of experience in managing large, complex projects, and we’re always amazed by the complexities we see when working on this scale. At these times, we’re happy to be a cog in a wheel so long as the value of our contribution to a project’s overall success is appreciated and respected – as it was in this case.

Our participation in these projects has had another consequence for our business: Our company includes many role players who specialize in one aspect or another of design, construction or maintenance, and these unusual projects give everyone the opportunity to branch out, exercise their creativity and pitch in where they can be of most use.

It’s good for morale, good for professional development, good for camaraderie – and great for building a skilled team: We see no limits; all we see are opportunities to shine.

To see a very brief video of the fountain in operation, click here.

Robert Nonemaker is co-owner of Outerspaces Inc., a design/build firm based in Glen Mills, Pa., that specializes in large, complex, high-end residential and commercial landscape, pool and fountain projects. He also owns Robert Nonemaker Exterior Design, a firm that offers design- and construction-consulting services to architects and landscape architects throughout the country.