Forming Flows

I was out of a job in Gloucester, England, several years back when I came across a collection of wonderfully unusual sculptures that changed my life.

These compositions, called Flowforms, were the work of British sculptor John Wilkes, an inspired artist who for most of his professional life has explored ways to use water’s nature and characteristics as his medium.

I was immediately drawn to what I saw: I’d worked as an estate gardener before being trained as a sculptor at the St. Martin School of Art in London and had always had an interest in natural forms and all sorts of experimental media. I had also spent a good part of my childhood utterly fascinated by water, watching how it beaded up and flowed down windowpanes in rainstorms, for example, or playing with spoons under faucets and observing the way different effects could be created simply by moving the concave surface beneath the flow.

As an art student, I had always known that I wanted to work with water and dreamed of ways I could treat it as a sculptural medium, but I had no clear idea how to do so until I saw my first Flowforms. I had never been truly inspired by mechanical displays, and fountain jets left me cold – but the charms of natural, flowing water never ceased to stir my imagination.

So I looked Wilkes up, knocked on his door and offered my services. Six months later, I was running a small production shop and making constructed wetlands with colleagues who also had worked with Wilkes. Thus began my career with Flowforms – an involvement that continues to this day.

SENSITIVE CHAOS

In the course of following the insights revealed by Wilkes’ work, I learned that his Flowforms concept extended directly from the pioneering research into water’s natural movement conducted by Theodor Schwenk.

Schwenk assembled his ideas into Sensitive Chaos, a 1963 book that reveals how water’s various shapes, forms, patterns and flows give rise to other shapes and forms we observe around us in nature – everything from wood grain, crystalline structures, animal shapes and ripples in sand to jellyfish physiology and human bone formations, all of which resemble responses to water’s forming ability. He further defined water’s role as the source of all life on our planet and then specifically defined humankind’s relationship with water’s movements and characteristics.

| While they may vaguely resemble physiological forms, these carefully contoured vessels are meant first and foremost to move water in interesting ways by enabling it to swirl and oscillate as it passes from vessel to vessel. |

John Wilkes carefully absorbed Schwenk’s work and, to make a very long story short, extrapolated from it to create sculptures that use water’s natural spiraling tendency as a means not only of making art, but also of increasing water’s ability to nourish.

Wilkes initially linked up with his mentor in Germany’s Black Forest region, joining a team headed by Schwenk that was investigating a variety of industrial processes that caused water to be compromised. Wilkes picked up the basic principles and carried them over to his sculptures, finding along the way that the results were not only visually compelling but were also having a noticeable effect on the water itself.

Coincidentally, I had read Sensitive Chaos long before I looked up Wilkes. The title of Schwenk’s book had been taken from a headnote written by Jacques Yves Cousteau in which he described the experience of a nighttime dive: “All around us arose from the living sea a hymn to the sensitive chaos.” I’d been a huge fan of Cousteau’s since childhood, had the honor of meeting his son and visited Calypso, Cousteau’s exploration vessel. In truth, I was initially drawn to Sensitive Chaos because of Cousteau’s contribution!

| We’ve found through our observations that passersby are fascinated by what they see in Flowforms. The various eddies, undulations and other flow patterns seem to want to be touched, interfered with and altered as the objects of simple playfulness. |

So having read Schwenk’s book and being excited about the concepts therein – then seeing Flowforms in Gloustchester and meeting John Wilkes – I recognized that I had finally found a means of combining my passion for water with my passion for art.

All of this ultimately led to my business collaboration with Christopher Mann, who was responsible for funding the development of Flowforms. He patented these systems and set up production and distribution channels for them across Europe before carrying the concept across the Atlantic to a base in Blue Hill, Maine, in association with the Water Research Institute and Jennifer Green. About 12 years ago, I joined Mann to get things going from headquarters we established in Wisconsin.

FORMS AND FLOWS

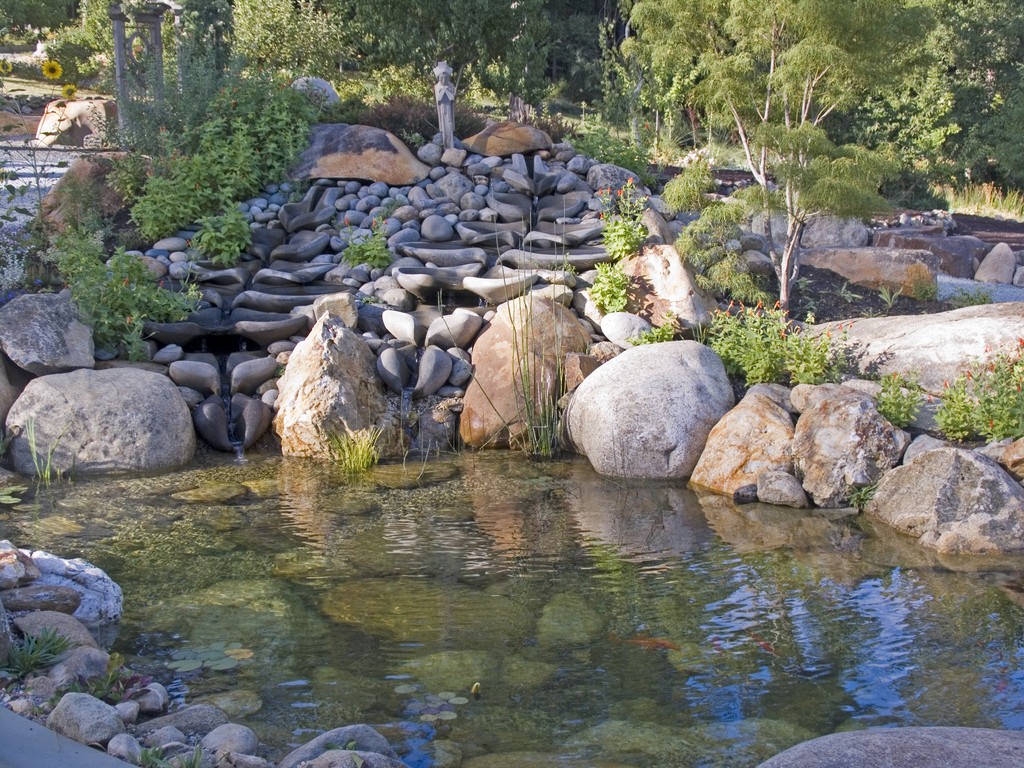

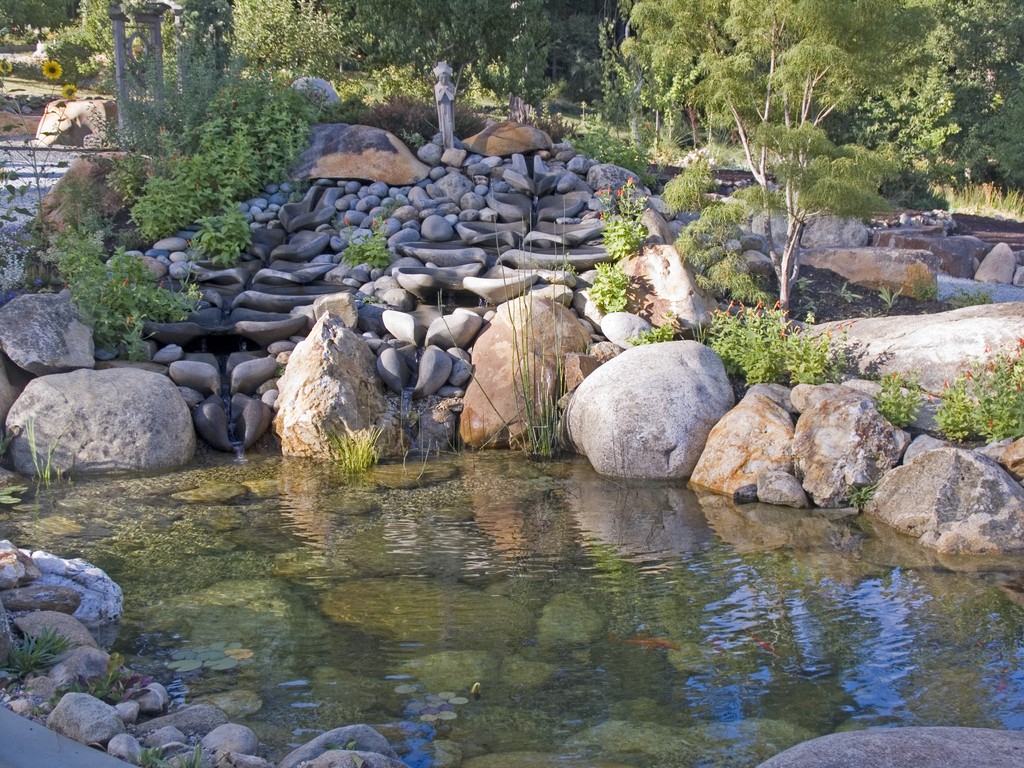

Flowforms articulate some of Schwenk’s observations and give them both artistic and practical expression. They are quite distinctive in design, existing at the margins where water moves between chaos (turbulence) and laminar flow and taking the form of crafted sculptures consisting of sequences of vessels arranged as either circular patterns or cascades. The water enters, spirals into a figure eight/infinity symbol within each vessel and then exits to move down the chain.

These principals of laminar flow, pooling and turbulent or chaotic flow – all observed by Schwenk – make for engaging visual experiences and are the principles that guide my work today. Indeed, I believe that water truly wants to move in these ways and that when systems pay attention to these principles, they appeal to observers on a variety of intuitive and physical levels.

| These sculptures take many forms, from simple ones that include just a vessel or two as the source of their distinctive flows. The formal one we installed in a public spot in Madison, Wis., seems to be just as popular with birds as it is with pedestrians. |

There’s a fundamental contradiction here in that it’s unusual in artistic endeavors to make water do anything, despite the fact that water has infinite shaping potential and these potentials are best worked with and not opposed. (When you work with water, you find harmony, peace and joy, but when water is either ignored or forced – as in the case of channels or dams – with time you get erosion, destruction and other negative outcomes.)

To resolve the contradiction, I as a sculptor with expertise in working with water surfaces allow the water itself to dictate the shapes of the vessels.

The design idea is that, as water enters one of the sculpted pools, it is pushed to the sides as more water fills the bowl. The small pools are contoured to accentuate that motion, helping the water spiral and oscillate. The spillways through which water enters and leaves these bowls are precisely sized to maintain the correct flow rate and volume needed to sustain and maximize the effects.

| In Europe, where the role of these sculptures in water treatment is widely established, they’ve even been installed at sewage-processing facilities to help improve water quality. In North America, by contrast, installations are less about functionality and more about aesthetics – and they’ve found their ways into a variety of beautiful spaces. |

In many designs, these vessels are symmetrical mirror images so the water flows within them in figure-eight patterns. This spiraling and oscillating action creates microscopically thin layers of water that slide past each other and generate a type of friction.

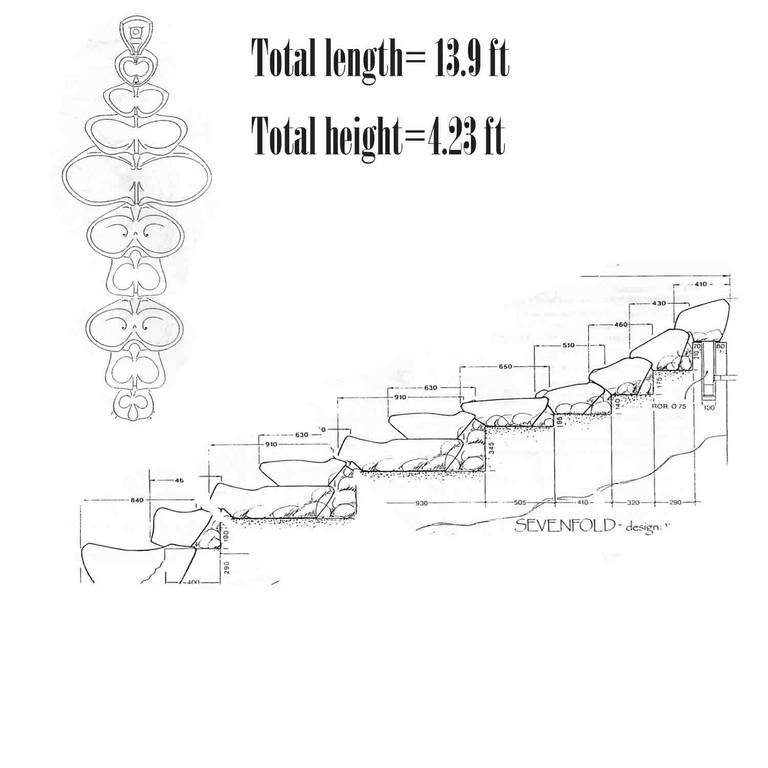

The design process for these visual chains can get tricky if you look at the individual vessels rather than the entire chain. To keep things clear, we start by defining a desired flow rate along the entirety of a desired drop in elevation. Once that signal value is known, we work in clay to form vessels sized to achieve the appropriate oscillating action.

At each level, the water’s characteristics determine the size and shape of the given vessel – each of which must be formed individually as though the water itself has done the shaping. Once each vessel in the chain is precisely contoured and we know through observation that it has been “tuned” to maximize the spiraling motion, we’ll cast it in metal, stone, glass or a composite material. In many cases, in fact, we’ll reproduce shapes over and over again across a range of media.

MAKING A DIFFERENCE

As suggested above, the swirling action actually seems to be a form of water treatment that enables us to deploy these systems to nourish plant material in constructed wetlands. That may come as a surprise, but Wilkes and others have extensively studied these issues and have verified the fact that water passing through a Flowform system makes the nutrients more readily available for plants.

To this point, research has isolated only the fact that this enhancement of the water happens, not how or why it is so. We all concede that, as yet, none of us is quite sure what’s going on in these situations or exactly why these positive effects take place. Research into the nature of these effects is ongoing; for now, we simply accept that something wonderful is happening.

|

Ongoing Research Various individuals and institutions around the world have pursued research on the topic since John Wilkes’ 1970 discovery of the “Flowform Principle.” The main studies have been conducted at Emerson College’s Healing Water Institute in Sussex, England. Significant ongoing research includes investigation and analysis of the effects of Flowform treatment on plant growth. Much of this is documented in Flowform Water Research, 1970-2007: A Collation of Research and Related Ideas – a vast compendium that, among many other things, covers studies that trace the growth patterns of lettuce, cress and wheat in a variety of field and laboratory conditions and also reports on water condition as measured at a number of Flowform installations around the world. Although the precise mechanisms are still to be determined, the findings consistently indicate that water treated with Flowforms embodies numerous beneficial effects, including measurable increases in plant growth relative to untreated tap water. These and other related documents can be found at www.healingwaterinstitute.org. S.S. |

In the time since we set up shop in the United States, we’ve made slow but steady progress, partly because we’re trying to overcome skepticism related to how the systems work, but also because water conservation and concerns over usage are “new” issues in the United States, at least as compared to Europe. So far, in fact, decisions about installing theses systems seem to be based on aesthetics: Some people think these vessels look odd or unusual, while others find them beautiful.

As we see it, an increasing awareness of the need to manage water resources more wisely will gradually carry people in our direction: Given our documentation of 30 percent increases in nutrient delivery, we’re gaining ground in constructed wetland applications and have strong cases to make with respect to both environmental and financial sustainability.

As a sculptor who sees beauty in these forms and their execution, I accept the mystery when it comes to water treatment and simply enjoy the thought that I can witness and even measure positive results in the growth of marker plant and insect species where these systems are installed.

Our strongest case at this point, however, has to do with aesthetics: We know that people are fascinated and soothed by flowing water. We know as well that these systems have a distinctive beauty from a distance – and then offer those who approach the vessels a chance to observe the swirling, oscillating currents and be fascinated by what they see, just as I was mesmerized as a child playing with spoons and faucets.

As new systems are installed and we take advantage of opportunities to watch how people respond to and interact with our sculptures, we can’t help noticing that children will (as children do) stop and stare and study what they see and clearly become engaged by the complexity of the flowing, pulsing water. Adults take more time to get into the rhythm of these watershapes, but they eventually “get it” as well.

We’ve monitored a large installation in downtown Madison, Wis., for some time now and have observed that even people who previously seem to be in a hurry will slow down and even stop to take a closer look at the system. There’s a clear softening of their facial expressions and body language, and occasionally these passersby will end up spending a good amount of time as Schwenk and Wilkes did, observing the water and gaining insights into how it moves along.

As we see it, these systems are based on ideas that are so fundamental that even adults who spend only a moderate amount of time observing them will be won over – a tribute to the overall aesthetics of the installation on the one hand and of the amazing appeal of water in motion on the other.

In view of all that, we’ve become patient with our progress: These systems are visually fascinating, and the added thought that they can also be good for the planet is a bonus as valuable as can be.

Sven Schunemann is co-founder of Flowforms America, Inc., and principal at Schunemann Water Design, both based in Mill Valley, Calif. A pioneer in the field of sustainable design and water-surface management, his work has focused mainly on the relationship between water use and energy consumption and on developing systems that result in conservation of both. He studied sculpture, photography and multimedia art at the St. Martin School of Art in London and has created a variety of integrated water/sculpture systems installed in high-profile settings, including the Princess Diana Memorial in Hyde Park, London, and Capitol Square in Madison, Wis.