First Do No Harm

Elevating the way we do things in this industry means addressing our gaps in knowledge on several levels.

First, excellence means understanding the aesthetic side of watershaping – design traditions, art history and the nature of visual appeal. Second (and right in step) is the need to know how to build various types of systems properly. As an industry, in other words, we need to know how to avoid mistakes.

In February, Genesis 3 staged a construction school in Orlando – and what follows isn’t a commercial; rather it’s a point of departure for a discussion long overdue in our industry. What struck me is that 60 students came to the school from all over the country (and beyond), and almost to a person they told us they came because they saw it as the only venue that offered focused, practical instruction on technical issues related to the construction of concrete vessels that contain water.

What disturbs me (and fuels the discussion that follows) is that this sort of basic, fundamental instruction hasn’t been available in all sorts of forums since the industry first started organizing itself in the 1950s and ’60s.

OVER TIME

Understanding how to build properly should, in my opinion, be the baseline requirement for entering the watershape-construction field, but obviously it’s not. Instead, we’ve had a largely seat-of-the-pants industry where knowledge is obtained by experience and informal instruction from people who may or may not be qualified to teach it. This is why mistakes and misconceptions are passed on – and sometimes even taught in seminars.

There really are only two ways to learn about his stuff: Either you learn by trial and error, or someone teaches you. I like to think that the second of those possibilities is the better path. One of my favorite axioms is, “A smart person learns from his or her mistakes; a smarter person learns from the mistakes of others.” Unfortunately, my own career until recently was a case study in the former.

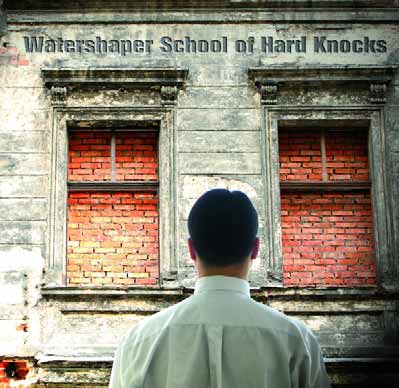

A large portion of my knowledge came through matriculation in the renowned School of Hard Knocks. (I’m sure you’ve seen it – there are campuses everywhere.) I actually started out in the business one summer at a resort where my occupation theretofore had been rubbing suntan lotion on pale bodies. In the course of my duties, I started taking care of the pool as well. Before long, I started my own pool service business, then began tackling repairs, then renovations, then construction. Now, after decades of rough-and-tumble experience, I work as a designer.

My own learning curve was slow, hard and full of mistakes. I’m a reasonably smart guy who pays attention and seeks new information, so I’ve been able to apply experience and develop successful businesses. Just the same, I can’t help wishing there would have been education available to me along the way that would have shortened the process and its pains. As it was, my story is riddled with incidents in which I learned the fundamentals the hard way.

I “learned” pool service at the hotel, for example, from a guy who had absolutely no idea what he was doing. We’d handle big chlorine-gas tanks in a facility where there might be hundreds of people around the pool as we worked. Sure enough, there were a couple of times we had to evacuate the deck because we thought we might have released poison gas.

I was a quick study and learned from those mistakes. Fortunately, nobody was ever hurt along the way, but the point of the story isn’t that we got away with it, but that we had no business servicing a commercial pool at all.

When I started building pools several years later, I was put in a position where I had to learn construction from my subcontractors. It was certainly an informal and haphazard way of picking up a trade, but looking back, it was the best resource available to me at the time. I made every effort to hire only experienced subs who came recommended by other people and was lucky enough to keep out of serious trouble, but there’s no question I was completely unqualified at the outset.

FLOATING ALONG

After a while, I obtained a license through the state that enabled me to perform as a commercial pool contractor. This required me to pass a test, so I took a class that gave me the information I needed – much of it involving general business information and the ins and outs of getting permits. By no means was this a course on (or a test about) the rigors commercial construction. There was nothing on soils, structural engineering or hydraulics, not by a long shot.

Ultimately, you might say I entered the pool business accidentally – and I have been far from alone in having found that path if the tales I’ve heard from others are anywhere close to the truth.

When you consider how many of us have learned construction more or less by osmosis, it’s a wonder there aren’t more failures. Yes, some projects do go south, sometimes in spectacular ways, but given the fact that watershape construction is an invasive, multifaceted undertaking that involves excavation, forming, plumbing, electrical installation and hardscape construction, it’s a wonder more people just don’t blow the whole deal on a daily basis.

In my case, there were a couple of minor mishaps that propelled my desire to do better, if only as a means of avoiding trouble. I sort of adopted the phrase from the medical profession’s Hippocratic oath, “First do no harm.”

When I had my service company, our clients included a couple who lived on golf course in Miami Beach. Their pool needed refurbishing, so we arranged to drain the pool, chip out the plaster and reinstall a new surface. We began by looking for a well point or water-control line that would let us pump the groundwater away from the area around the pool – a common practice in Florida because of extremely high water tables.

We couldn’t find such a line, so we assumed (a deadly choice) that, because the pool had been there since before World War II, it had doubtless been drained several times and so it must be safe. We set up the submersible pump, ran the water out to the street and drained the pool overnight.

Bad move: The next morning started with frantic calls from the clients saying they’d heard cracking sounds and loud rumbling from the backyard all night long – not good. I stopped by the property on the way to the office and saw that the pool had lifted six inches above grade at the shallow end. The pool was only partially drained by that time, so I turned off the pump so things wouldn’t get any worse.

SAD SAGAS

We refilled the pool, which helped it settle back down by a full four inches, but it was still two inches out of level. At that point, we obtained the pool plans from the city archives and saw that the original plans specified a hydrostatic-relief valve in the main drain. We sent a diver down to check it out and found that the well-rusted valve had been set in place but had been covered over with concrete.

Thinking fast, we drained the pool as far as we could without it beginning to float back up, then drilled a hole in the floor of the pool at the lowest level we could reach. Next, we pushed a perforated plumbing line through the hole, hooked up a pump and began draining water from underneath and around the pool.

This draining process took a long couple of days, but when the pump ran dry, we were able to drain the rest of the water from the pool and began the refinishing process. We were able to get the pool back to within an inch or so of its original level and were able to fudge things by replacing the coping and rebuilding part of the patio, mostly at our own expense.

Basically, we got lucky and learned important lessons about what it took to float a pool and then deal with the problems that ensued. (Much later, I also learned from a soils engineer that this particular area had a number of underground rivers – what a planet!) Forevermore, I learned that our structures exist in dynamic conditions that we can’t see, and I’ve been cautious about soils and doing things right ever since.

I’ve built many pools in the Miami Beach area since then, and it’s no surprise to me in looking back how many of those pools have been constructed on pilings. We also made it a habit to install a layer of rock beneath the pool and include runs of perforated piping that can be used as well points to relieve hydrostatic pressure whenever a pool might need to be drained later on.

The long and short of the story is that I have since developed relationships with soils engineers and geologists in the area and obtain proper soils data on every single pool site I touch. As essential and fundamental as that step is (or at least should be), I still run into lots of builders who use off-the-shelf construction details designed without any specific knowledge of prevailing geological or soils conditions.

Unfortunately, I fear that a great many of those practitioners will feel the sting of a major structural failure before they wise up and start doing things the right way.

You can, of course, choose to learn entirely by doing, but along the way you will inflict needless pain on yourself. The alternative is to seek out people who are willing to share their experiences and help you avoid mistakes in the first place.

I, among many others, am a huge believer that our industry has needed that sort of open information exchange for a long time. Sure, we talk about it a lot, but the fact is those forums for education and information exchange barely exist, even today.

THE FRONT-RUNNER FEE

Some people go to great effort to hide their failures, seeing past problems as life’s very private way of teaching lessons and strengthening character; others go farther, saying that sharing those lessons is tantamount to giving aid and comfort to the competition. Either way, the misers who keep their experiences to themselves are misguided.

First of all, nobody’s work history is mistake-free; second, what’s the value of being part of an industry that doesn’t advance the expertise of its members? The idea that we benefit because of mistakes made by our competitors is just plain crazy: It’s more than mere idealism to believe that we’re all elevated when the tide of competency rises within the industry as a whole. Why not share when the information you have can pull everyone up?

Look at it this way: The painful costs of experience are an investment in knowledge so long as you’re willing to learn and pass the lessons along. This is why I see mistakes as a form of innovation and rectifying them as an investment I call “paying the front-runner fee.” Through sharing and education, we all can reap the benefits of the investments of those who have taken it upon themselves to pay that fee.

What upsets me (and really boggles my mind) are the people out there who criticize education programs because they don’t like the fact that we’re sharing so-called “trade secrets.” Likewise, I’ve been confronted by people who are upset that I tell others in the trade that design consulting is a valid profession. It’s all about fear of change, and I can only ask: What kind of businessperson is afraid of change when the one thing we know for sure is that change is the only certainty?

The response might be that having paid the “fee” themselves and probably having suffered financial and even emotional consequences, these folks feel no compulsion to make life easier for others following in their footsteps and trying to do the same things. I believe that viewpoint is narrow-minded, and extremely so.

Yes, I’m proud of the work we’ve done with Genesis 3 in establishing sound educational programs, but the fact that what we’re doing is out of the norm is a disturbing indication that shortsightedness is still a debilitating fixture in our industry.

RULE BOOKS

Sticking to the status quo is a problem in any industry, but in our case as watershapers it’s particularly horrific because we’re working a field that doesn’t have any sort of rulebook.

The Uniform Building Code, local health department codes and the various industry-published standards are all rudimentary and aimed simply at avoiding lawsuits. When it comes to innovations related to plumbing for perimeter-overflow systems, for example, we’re left on our own to advance our understanding. As a result, when it comes to any of the more creative elements of watershaping, it’s even more important that ideas be exchanged fluidly. Either that, or the front-runner fee is going to be paid by a senselessly large number of people.

I could write at length about the various fees I’ve paid in pursuit of innovation and design creativity, and I’ve been able through my writing and in classrooms to share the dividends with others – and I make no bones of the fact that I feel good about it. There is great satisfaction that comes from helping other people – and indeed from being helped in return.

The nice thing about experience is that each and every one of us can find opportunities to share what we know. I believe that if more people in this industry viewed lessons they’ve learned as an investment that can be of great benefit to the industry at large, construction education would become as commonplace as it should be.

Our clients deserve to work with professionals who not only know how to sell and wow the client, but also can assure them that the work will be done reliably with every effort made to prevent costly and frustrating failures down the line. We may be competitors, but we have a common interest in the success and advancement of the art of watershaping. We therefore owe it to ourselves – and our clients – to use our experiences for the benefit of one and all.

Brian Van Bower runs Aquatic Consultants, a design firm based in Miami, Fla., and is a co-founder of the Genesis 3 Design Group; dedicated to top-of-the-line performance in aquatic design and construction, this organization conducts schools for like-minded pool designers and builders. He can be reached at bvanbower@aol.com.