Finding the Cure

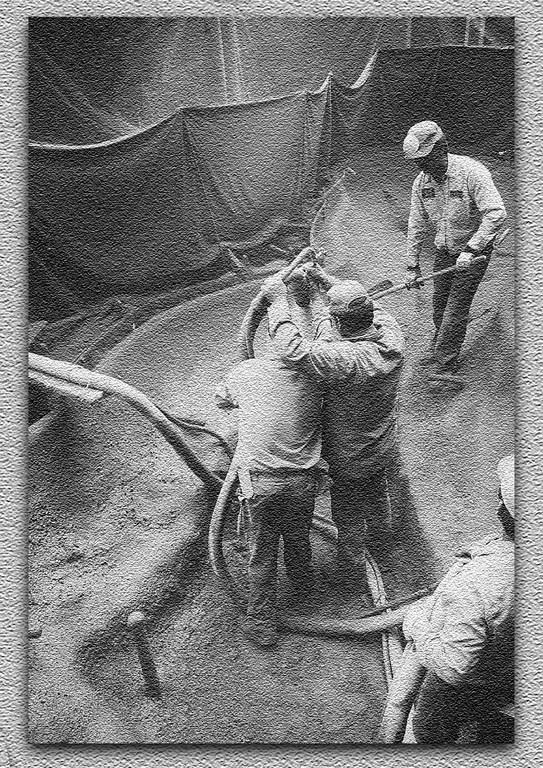

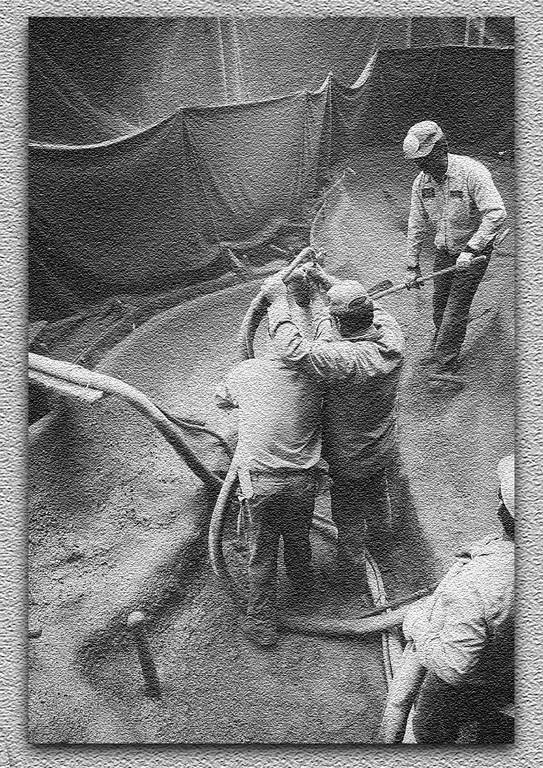

As a former shotcrete builder myself, I believe you can’t find a better method of building a pool, spa, pond or waterfeature of any type than by using pneumatically placed concrete, or “shotcrete.” The method and the material offer the designer and builder great and often incredible design flexibility, and the resulting watershapes will last several lifetimes.

Given that the vast majority of watershapers around the world depend on shotcrete as their primary construction material, it only makes sense that we should know as much as possible about putting this amazing product to its best possible use. Unfortunately, however, that’s not always the case.

There’s little argument that the process of shotcrete construction is laborious and demanding, that it requires a major logistical and physical effort and that fairly precise timing is necessary. For all the focus it takes to apply it and shape it just so, however, I have observed a couple of critical steps many builders overlook in the press of getting the job done – the most important of them being the proper curing of the concrete shell.

NO EXCUSES

The contractor is the expert – the owner’s hired gun, as it were. As the professional called in to do the work, he or she is wholly responsible for the installation of a quality product, meaning the builder is responsible for properly completing each and every step of the construction process – and that includes curing the shell.

If everyone were doing just what they’re supposed to, we’d never hear the statement, “Shrinkage cracks occur naturally; that’s just what concrete does.” But we do hear it, time and time again.

The simple fact is that if you don’t cure the shell, moisture exits the concrete too quickly, making the material lose mass and shrink. The result is unsightly cracks in the plaster finish, and this is not “just something that concrete does.” It is, in fact, entirely the result of skipping a key step in the application process. And the sad thing is that curing involves nothing more than keeping the shell moist for a few days. That’s all there is to it.

As you can probably tell, this is a pet peeve of mine. I’ve said over and over that, as an industry, we need to step up and take responsibility for what we do through our carelessness. It’s simply not good enough to blame shrinkage cracks on Mother Nature. Nor is it sufficient to leave the curing process up to the customer. Look at it this way: When highways and bridge decks are being built, taxpayers don’t stay on site wetting down the concrete. That task belongs to the contractor, not the owner.

Pool builders have exactly that same obligation in their performance of construction tasks. And all it takes during hot and dry periods of the year is wetting the surface. There are other ways to do it, and there obviously are local climatic conditions that come into play – including temperature, humidity, winds and more – that may force you to adjust the process a bit.

| Much Ado About Something

The importance of curing is real. In fact, the necessity for taking all the time needed for effective curing has long been recognized by people who study concrete in all its forms. As the Portland Cement Association’s guidebook, Design and Control of Concrete Mixtures, clearly states, “Since all the desirable properties of concrete are improved by curing, the curing period should be as long as practical.” Proper protection of freshly placed concrete must occur during cold-weather shotcreting as well as hot-weather shotcreting and is paramount to providing quality control and assurance. The American Concrete Institute’s Specification for Shotcrete (ACI 506.2-95) is clear on this point: “Cure immediately after finishing,” it says. Beyond that, the ACI offers additional guidance: [ ] Cure shotcrete continuously by maintaining it in a moist condition for seven days or until the specified strength is attained or until succeeding shotcrete layers are placed. [ ] Cure by one of the following methods: ponding, continuous sprinkling or covering with impervious sheet material, moist canvas or burlap. [ ] Natural curing shall be permitted if the ambient relative humidity is maintained above 95 percent.– C.S. |

But we’re not talking about a great deal of technical sophistication here. In fact, I’d say that all of this really just boils down to plain old common sense: One way or another, you’ve got to keep the freshly placed shotcrete wet!

KEEPING IT WET

Basically, “wetting” means keeping the concrete moist enough so that the mix doesn’t set too quickly. In other words, you’re trying to slow down the hydration and evaporation processes.

In essence, when the concrete sets (or dries), moisture exits the mix and, as was mentioned above, the mass of the concrete is reduced. When this happens too quickly, cracks form in the shell and likely will transfer to the plaster surface you’ll apply later.

The simplest method for moisture curing is to set up oscillating sprinklers on a tripod, aligned in such a way that water is broadcast over the entire surface of the shell. Another method is to place a drip/weep hose around the full circumference of the bond beam, then allow the water to run down the walls.

(You can use a submersible pump with either method. Once you have a reserve water supply in the bowl of the shell, you can recirculate and conserve the water with ease.)

However you choose to dispense the water, it’s absolutely imperative that the entire surface receives water for a minimum of three days, and preferably seven days. This will achieve complete hydration and dramatically reduce any drying shrinkage.

And if you’ve forgotten what drying shrinkage looks like, take a look at the larger masses of concrete in shells, particularly around steps and benches. Because there’s more concrete in these areas, the effects of improper curing are seen there to a greater degree, hence the common problem of shrinkage cracks around steps.

The ideal time to start moisture curing and avoid shrinkage cracks is as soon possible after shooting and finishing. Your timing here is definitely important, but you don’t have to be over-zealous about this and dilute the shotcrete at the surface of the shell. Basically, you want to slow the hydration/drying process to allow the concrete to achieve its greatest strength. Your purpose is keeping the concrete damp, not flooding the shell.

HOT AND COLD

In some cases, shrinkage cracking is less a product of skipping the curing step than it is of trying to apply shotcrete under adverse conditions – that is, conditions hostile to proper curing.

To be sure, placing a shell in weather that is either too hot or too cold will have effects similar to those you see when you ignore curing altogether. Fortunately, researchers at the American Concrete Institute offer advice on these issues.

| In Concrete Terms

I’ve heard many explanations about the differences between shotcrete and gunite, the latter being a term that’s commonly been used in the pool industry for the better part of the 20th Century. Unfortunately, most of the definitions offered up in the pool industry are wrong, at least according to the American Concrete Institute. Paraphrasing a bit, here’s the way the ACI breaks it all down: • Shotcrete is the term used to describe all forms of “pneumatically placed concrete.” In other words, it’s all shotcrete, no matter whether the water is mixed with the concrete at the nozzle or if it comes out as a wet mix. The two methods are appropriately known as the “dry-mix method” and the “wet-mix method.” • Gunite, perhaps the most familiar term used to describe pneumatically placed concrete, has no official meaning in ACI documentation. The term first emerged as a trade name coined in the 1930s by the Allentown Gun Company of Allentown, Pa. It was used to describe the company’s proprietary method for applying pneumatically placed concrete. One of the first applications of “Gunite” was in repairing airstrips damaged in battle during World War II. As time passed and Allentown Gun’s method became popular for placing swimming pool shells, the term caught on as a generic name for the process of applying a material that is more properly called shotcrete. – C.S. |

[ ] Hot weather shotcreting: Do not apply shotcrete when the material temperature is above 90 degrees Fahrenheit for wet mix shotcrete or 100 degrees for the dry mix often referred to as gunite. (See the sidebar at right to learn more about the terms “shotcrete” and “gunite.”) It’s important to note that ACI is referring here to material temperature rather than ambient temperature. Fortunately, it’s somewhat easier to control the temperature of the concrete than it is to master the weather.

[ ] Cold weather shotcreting: Shooting may proceed when ambient temperature is 40 degrees Fahrenheit and rising, or 50 degrees and rising for latex-modified shotcrete. Shooting should not proceed, says ACI, when ambient temperature is 40 degrees and falling.

[ ] Material temperature: At time of application, the material temperature of the shotcrete should not be less than 50 degrees or more than 90 degrees. And under no circumstances, says ACI, should shotcrete be applied to frozen surfaces.

[ ] Protective measures: There are many methods of protecting the shell after it has been shot during cold weather. One of the simplest and most effective, according to ACI, is placing a heater in the deep end then covering the pool with a vinyl air structure. (Sheet vinyl and lumber also work well in fabricating an enclosure that will maintain air temperatures in the desired 50 to 70 degree range.)

ACI advises that you should expect to lose moisture during this process and that you should anticipate dampening the surface even though the humidity in any enclosure may increase. The enclosure must also be properly ventilated, depending on the type of fuel used by the heater. Exposing freshly placed shotcrete to exhaust gases, for example, may cause dusting as a result of rapid carbonation. Under such circumstances, it may be beneficial to pressure wash the surface prior to applying a finish.

WE BUILD TO LAST

Most of the concrete pools I evaluate in my consulting business will probably outlast us all. But I have also seen pools in which the concrete was abused after application. It simply amazes me to think about all the effort that goes into excavating, forming, placing the steel, installing the plumbing, doing the electrical work and shooting the shell – and then to see that the builder has cut a corner or two and exposed the shell to conditions that will do it harm.

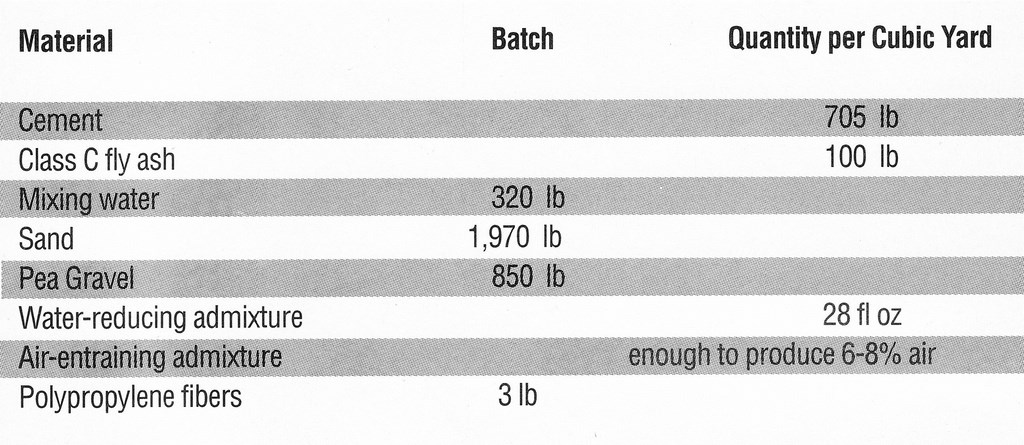

| Wet-mix shotcrete has caught in recent years for many reasons, not the least of which is the fact that by mixing the water and cement before it’s pumped out of the nozzle, the nozzleman can focus a greater degree of attention on forming the shell. In addition, wet-mix shotcrete can contain some coarse aggregate, which adds to its strength. Because it has a higher water content, however, wet-mix shotcrete presents a greater potential for shrinkage – a potential you can counterbalance by proper curing and through use of water-reducing admixtures as part of the mix. These admixtures help maintain a low water-to-cement ratio. As an example of what this means, below is a recipe I recommend for wet-mix shotcrete for many jobs in the Midwest: |

Along the way, it also exposes the builder to the possibility of expensive litigation.

As covered here, this failure on the part of any builder is inexcusable. In fact, it probably takes more time to pull a permit than it does to set up a curing system that really works. And if the liability issues aren’t enough to motivate better curing practices, consider the fact that you sacrifice as much as 50% of the strength of the mix design through improper curing.

No matter what the weather conditions, the builder is responsible for the structure during the entire course of construction and on into the warranty period. In our litigious society, contractors who fall short in any way should expect to defend themselves in a courtroom if they are not doing the job – the whole job – according to standards set forth not by the pool industry, but rather by ACI and the reinforced-concrete industry.

The effort required to address this issue is minimal, and I can’t see it being worth going to court or even having to answer the same question over and over again: “What’s up with all those little cracks?”

Curt Straub has been active in the pool industry since 1962, when he joined his family’s construction company as a laborer. By 1970, he had stepped up to head the company’s design and sales teams, positions he held until 1990, when he founded Aquatic Consultants. A specialist in pool and spa design, he offers mediation and conflict-resolution services along with his emphasis on structural evaluation. Straub is a longtime member of the American Concrete Institute and past chairman of ACI’s swimming pool committee. He is also a past board member of the Master Pools Guild.