Finding Flaw & Future Favor

What does it mean to create something that qualifies as “great”? Is it originality and inventiveness, reliability and function, or the ability to withstand the test of time, or all of those? Here Jeff Freeman & Mark Holden dissect that question with a look at the rehabilitation of a truly iconic and complex fountain system at the Los Angeles Music Center.

By Jeff Freeman and Mark Holden

When all of our senses and intellect tell us we have succeeded in creating a “good” or even “great” watershape, I believe there should be a moment of introspection when we consider whether we really have, in fact, accomplished something remarkable, or not.

We’ve found that when we step back from the rigors of the work and take a bird’s-eye view of the work, sometimes it’s not always so easy to know for sure.

Consider truly historic accomplishments that are regarded in a light that doesn’t always reflect the entire truth. Frank Lloyd Wright’s homes were inspiring and many would argue redefined modern architecture, but now many of those historic structures leak like a sieve and are falling apart. The magical DeLorean automobile was beautiful and futuristic but was almost undrivable and never manifested anything as far a functional vehicle. Sigmund Freud’s model of the human psyche transformed modern psychiatry, but has since been debunked countless times as a manifestation of his own neurosis.

These were all sources of intellectual or technical advancement that we learned over time were, in fact, flawed in one way or another. In the world of watershaping, we see many similar examples. Places like the Palace of Versailles, Villa d’ Este, or the fountains of Rome, all advanced the art of watershape design by centuries, but over time, also provided valuable lessons about functionality, sustained performance and aesthetics.

In today’s world of watershaping, we see countless expensive backyard pools with multimillion dollar budgets integrated with every contraption that is known to mankind. Similarly we see resort properties with wonderfully inventive designs that entertain and inspire millions of people the world over. Yet, we can’t but wonder, are we really impressed? And do they really pass the test of time? Many, if not most, of these spaces get remodeled within five years in some capacity.

So, the question remains of what is great or good when it comes to our work?

SEEING THROUH EXPERIENCE

Considering that question through the lens of forensics focuses a different viewfinder on the level of enduring quality. In our work here at Holdenwater, we routinely look at failing projects in an attempt to help them establish a healthier operation and longer life.

When presented with a new diagnostic or restoration project, we must compartmentalize our past experiences and look at each new opportunity with fresh eyes. Past examples have always thrown curve balls at us during the forensic process, and these unique situations quite often require similarly unique solutions.

This process of objectively seeing deficiencies, reporting of the findings and finally seeking solutions that fit the scenario are key to effective rehabilitation of water elements that have fallen from their original glory in some way, either mechanically or structurally.

Here’s the proverbial catch: most people want to fix something that is seen as broken, but many people do not look at why something went awry to begin with. Quick solutions sometimes allow for problems to reoccur. Sourcing the reasons ‘why’ can develop a rehabilitation that prevents future issues. Some forensic situations that we have worked on have nothing to do with the actual watershape and actually stem from some outside source.

One set of examples: we have found massive corrosion of stainless-steel pools caused by outside stray current and EMF from nearby high-voltage train systems, destroyed concrete pool decks from poor steel placement combined with high chlorides in pool water, and mechanical systems that failed due to poor maintenance, poor ventilation and sub-standard long-term care.

These outside pressures cannot always be eliminated; so, we must then look to solutions that adapt to these environmental factors instead of just repairing a material or system to have it fail again. Also, the question exists, “why do we not take these criteria into consideration to begin with?” There are many ways to answer that question. One thing to consider is that many of these aging features were created decades ago at times when there were no real watershaping standards for design, engineering and materials.

As we move forward, equipped with our 21st century toolbelt, I believe we have an opportunity to correct the shortcomings of the past and advance our works with durability, sustained function and efficiency in mind, while preserving and even expanding on what made these works seem so “great” in the first place.

A CENTER FOR MUSIC

One of these opportunities came our way in the form of a legendary water feature in downtown Los Angeles, Calif. The Los Angeles Music Center (LAMC) — home of the LA Philharmonic — is located in the heart of the city just west of city hall in a complex that includes the famous Dorothy Chandler Pavilion, Ahmanson Theatre and the Mark Taper Forum.

Its central plaza courtyard is home to one of the earliest leap-jet interactive features created, at least in the modern era. Developed and installed in 1969-70, the now iconic feature surrounded a prominent central 25-foot bronze statue created by artist Jacques Lipchitz, while providing a dazzling spectacle that helped redefine high-profile public spaces.

The LAMC and its architects were looking to create a new, more contemporary and interactive, centerpiece for the famous but aging plaza. This involved moving the statue, rehabilitating the fountain system and integrating cutting edge interactive video screens for exterior theatrical performances in the plaza. In effect, they wanted to keep the feature while also transforming the location into a public-use space; whereas, before it was purely decorative. (This is one of the great advantages of leaping jet features; when they aren’t operating, they create a useable space.)

We were first retained to figure out the health of the water feature and surrounding paving. In short, it was in bad shape — a half-century of use had taken a toll. Luckily there were detailed design documents of the original construction, with an updated set of a partial remodel that took place in the 1980s. Both were comprehensive for the time period but were dated compared to techniques and materials of today.

In our forensic evaluation, we discovered heavy corrosion in the existing iron pipes, a deficient circulation system by current standards, a lighting system of 140 halogen fixtures (35,000 watts) that partially worked and a waterproofing system that had deteriorated. And we discovered that the feature’s water chemistry had completely corroded the rebar in the paving tiles.

Overall, this was an example of an older feature that lacked many of the new inventions utilized in modern watershapes. So, it was fair to say that this rehabilitation had a fairly straightforward forensic process and solution program, for the most part.

It was a challenge that became part of our lives from 2016-19. We were part of an accomplished project team, the process was drawn out and complex, but in the end I believe we came up with the correct solutions. We were fortunate that the local Health Department was also helpful in making this historic feature a reality. Their acceptance helped us immeasurably.

LIGHTING UP

The existing lighting system consisted of 140 fixtures, each at 250 watts, totaling a 35,000-watt consumption. By today’s standards this is astronomically expensive to operate. Modern LED lamps can match the performance, are color changing, operate at one eighth the consumption and have much longer bulb lifespans.

The issue was that there are 140 of them, each with NEMA cords connecting to large underwater junction boxes. The maintenance to change one bulb meant draining the feature, removing the paving stones and performing surgery on the junction box potting compound every time there was an issue.

We looked outside of the water feature industry to a light manufacturer from Canada called CCEI. Their inductive lighting allowed us to have a bulb-replacement mechanism that did not require all of the effort of other manufacturers. We consulted with their design team to establish a custom layout of 140 inductive fixtures with drivers and a control module that allowed for a custom color light show to be programmed in a very simplistic manner.

To get the new lights to sit vertically each fixture had a custom stainless steel U-shaped support bracket. The cords were then brought to a dry junction box that did not need the potting compound. When a lamp dies and becomes inoperable, a service technician simply inserts a new one without removing anything. It solved all issues and was, in our way of thinking, an outside the box solution.

The end result was a cutting-edge system that was very cost effective compared to the other conventional water feature systems available to us.

A SPECTACLE OF SPRAY

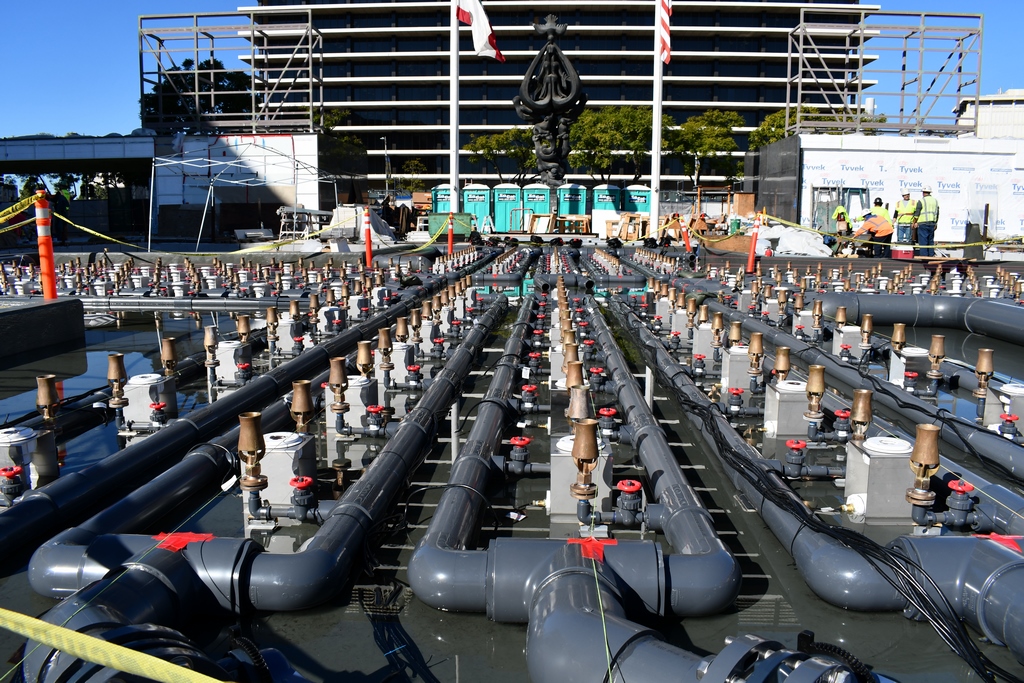

The fountain system itself was in bad shape. We had to remove all of the pavers and ferrous plumbing. The idea was to recreate the layout and functionality of the existing system, but with new technology. In all, the system consists of 280 leaping jets with the 140 aforementioned lights. It required all new plumbing, with pipes ranging in diameter from 6 to 12 inches.

We also replaced all the pavers. The new pavers do not include structural steel, but gain their strength from the advanced material and compressive values. Thus, the pavers would not be subject to corrosion like the previously used steel-reinforced pavers.

Luckily the aggressive water chemistry of the existing feature kept the bronze nozzles spotless for decades. They only needed some minor touch up and were reinstalled on new Schedule 80 PVC distribution manifolds. This spider web of plumbing took many months to install but proved to equalize the performance of each nozzle. Flow control valves were set at various stages to help with the finetuning of performance.

Amazingly, the system only holds about 15,000 gallons of water, which is now treated with chlorine and UV sterilization. The entire system is contained within a basin that is only nine inches deep. This is where the water is held when the system is operating, typical of deck-level leaping jet features.

All of the computer controls and performance pumps were left in operation, needing only minor repairs. The only addition to this system was to repair the anemometer to lower the nozzles in the event of high-wind conditions. The entire thing is run by four 40-hp pumps that were also completely reconditioned.

So, with a forensic process to ascertain what the challenges were and our collaboration with the entire design team to help bring this feature up-to-date correctly including plaza upgrades, we were able to bring new life to an iconic feature that is now set to play its role in media events of the future.

We plan to present other forensic-based projects in future editions.

Jeff Freeman has been a leader and innovator in the water-quality industry for over 30 years. In addition to lecturing and guiding agency regulatory policy, he has dedicated his career to advancing the technology of water purification and sanitization. He is Certified Pool Operator (CPO) and has U.S. military certification for water environments.

Mark Holden is president and founder of Holdenwater, a watershaping design and engineering firm based on Fullerton, Calif. He has extensive experience teaching watershaping history and design, and is one of WaterShapes most published authors.