Field of Streams

Landscaping has to be something special to harmonize with the amazing natural surroundings of places such as we encountered with the Colony at White Pine Canyon: Set on 4,000 acres near the famed ski slopes at Park City, Utah, the resort/homestead project was to have watershapes second to none when it came to their natural beauty.

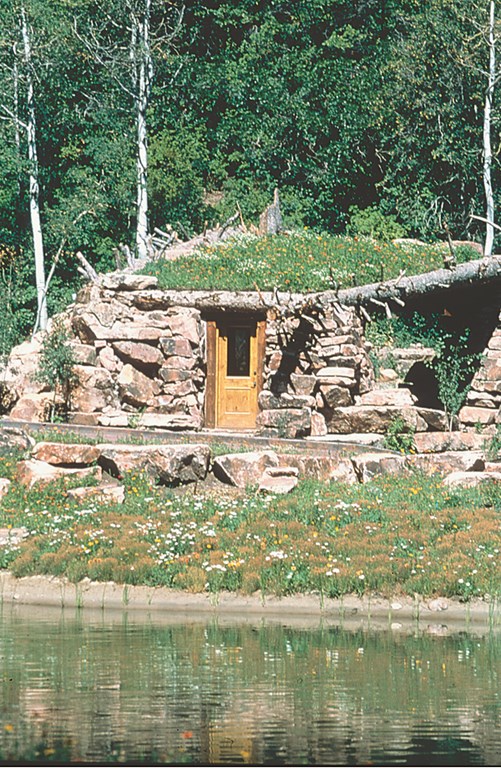

Indeed, water was central to the entire plan. We at Land Expressions of Mead, Wash., were engaged by the developer, Iron Mountain Associates of Salt Lake City, to execute an 830-foot stream, a 34-foot cascading waterfall and a sprawling quarter-million-gallon pond. All of this came along with an array of natural plantings, pathways, a 500,000-gallon water tank surmounted by a five-acre meadow, and a guard shack made from rocks, sod and a fallen tree.

Projects of this sort don’t come along very often – and when they do, they call for creativity, preparation and planning on a grand scale. In this case it, also meant working at (literally) breathtaking altitudes and in a small window of opportunity between snow seasons – all while infusing the work with intricate detail.

Here’s a look at how it all came together.

BIG SKY

The whole world became aware of the rugged beauty of the Rocky Mountains during the 2002 Olympic Winter Games. Our project was in a valley adjacent to Park City’s slopes, which served as a venue for many of the Games’ alpine skiing events.

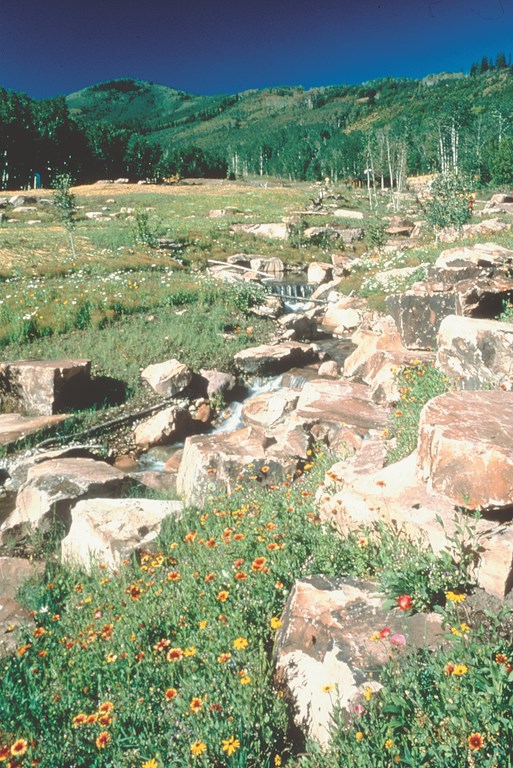

The area gets a lot of snow, but during its brief summers the area’s rolling meadows, stark rock outcroppings and stands of majestic pines and aspens emerge on a huge scale. Making our work fit within these surroundings meant using all-natural materials on a similarly grand scale – and quickly!

In doing so, we had a lucky break right away: The property’s ski runs and infrastructure were also under construction at the time we came on site so we were able to pick and choose from a vast amount of rock and plant material that had been excavated and scraped away to shape the ski runs.

The client also asked us to use large stones that were available at a landslide area located on the property at an altitude of 9,300 feet. To access the area, the owner built roads and supplied an excavator and trucks – and we pulled out tons of a sandstone material that conveniently wanted to break into large flat pieces, typically six or seven feet in diameter and about a foot thick.

| THE BIRTH OF A STREAM: Setting up the 830-foot streambed was basically a matter of being methodical once the course had been set (left). First the 30-mil liner was moved into place (middle left), then, after the channel had been lined with concrete, the major stones were positioned (middle right). Once the largest rocks had been mortared, cobble and gravel were added (right) – not quite ready for water, but close. |

This mostly flat, pink-hued material was wonderful for covering ground space, which is important in such a large project. In fact, we had so much material available that it was much easier than it would have been otherwise to maintain natural appearances while creating a variety of points for human interaction with the water. In all, we pulled out and used approximately 2,000 tons of this stone.

Working so high up, however, meant that we had to execute the entire project between late-season snows that stopped in June 2001 and early-season flurries that blew in during August. It also meant that we were constantly adjusting and readjusting our vehicle’s carburetors so they would operate at the high elevations.

Throughout the project there were, at times, up to seven working on site, including stone-setting artist Max Slater, a specialist whom we often turn to when we want things to look as natural as possible. As mentioned above, the scale and the timetable required us to have a thorough game plan in place before we started.

But as anyone who has worked on naturalistic projects knows well, most of the aesthetic work can only be done on site during excavation and especially in placement of the stone material – and that was certainly the case for this project. We’d prepared overhead plans that gave us a rough idea of what went where, but our work of mimicking the natural look of the indigenous plantings and rock outcroppings all took place at ground level and in a compressed time frame.

FLOW-THROUGH INTEGRATIONS

The design included a long stream that winds its way along the main entrance to the property before terminating in a large pond next to the facility’s gatehouse and sales office. A central waterfall provides vigorous cascades next to the road; the outflow is routed beneath the road before it, too, flows to the main pond.

In approaching our tasks, we had to be keenly aware of the fact that the valley in which we were working includes natural drainage year ’round, to the tune of 40 to 60 gallons per minute.

We knew we’d need to accommodate and use that flow in and out of our own watershape system. To that end, water is collected in a huge sump upslope of the landscaped area before being released into a series of ponds next to the development’s post office. The natural runoff supplements the stream’s pumped flow of 400 gpm.

| A SENSE OF SCALE: We’re not often asked to install 250,000-gallon ponds, and the scale of the work is admittedly a bit intimidating. The structure under construction in the back is plenty big, but it’s made to seem smaller by the extent of the excavation (left), and the memory of hand-dragging the liner to fill the gap is one we won’t soon forget (middle). Ultimately, however, structure and pond came together in a beautiful overall composition (right). |

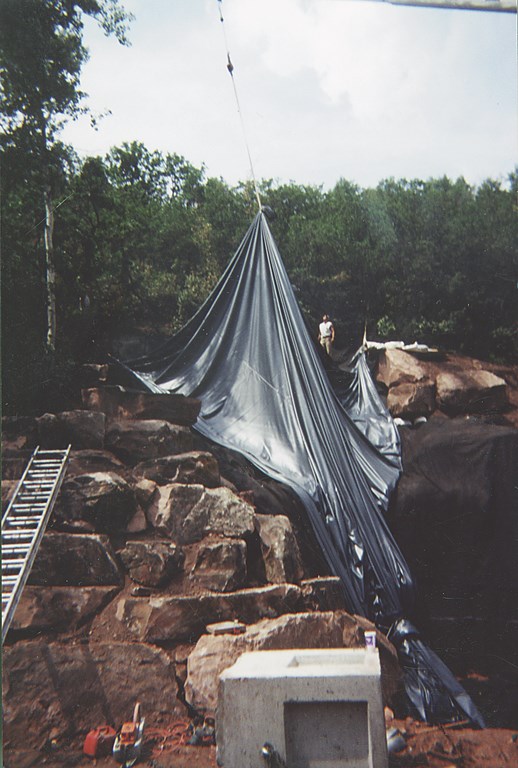

The stream, waterfall and pond were formed using a 30-mil liner that was set and then covered with concrete. (The bottom of the pond was subsequently covered with a foot-thick layer of sand.) We ended up using more than 25,000 square feet of liner, some of its sections so large that we had to move them into place using a crane.

In concept and basic operation, water systems such as these are mechanically simple. On the stream, for example, a 20-horsepower pump moves water from the main pond to the basin at the top of the stream through a single, six-inch plumbing line. Gravity does the rest as the upper pond overflows into the streambed. Similarly, a 25-hp pump and a single eight-inch line handle the flow for the waterfall.

The complexity of the installation comes in managing scale and jockeying the schedule while simultaneously working to infuse all of the work with the level of natural detail the client required. Much of what we were doing on various sections of the project moved forward at the same time, all of it with constant input and feedback from the owner.

GOING WITH THE FLOW

The stream crosses a gentle slope, dropping about 70 feet along its 830-foot course, which gave us a nice interval to work with in creating cascades as well as meandering areas, riffle and ponds that will eventually serve as homes to fish. Still, containing and controlling the huge volume of water needed to wet 830 feet of stream with that much slope brings challenges with it, no matter how fortunate the existing lay of the land.

So we dug in, methodically excavating gentle banks where we knew we could carefully obliterate the transition from streambed to the surrounding landscaping using a mixture of stone, sod and plants. The detailing took a great deal of time: We spent days selecting stones for the transitions and banks of the stream. Some of the material came from the ski slopes; other pieces were collected at the landslide area, while more came from surrounding fields.

| SUDDENLY GREEN: Once the watercourses were set, we needed to re-establish the meadow and plant the areas surrounding the stream on both sides. We accomplished this with a combination of wildflower sod and by hydroseeding the area with native grass (left). The result was a carpet of greenery that soon looked like it had always been there (right). |

The flat planes and sharp contours of the sandstone material were crucial in creating natural-looking access points to the water as well as easy transitions at the edges of the streambed. We also used a tremendous amount of crushed rock. The fines created a gravel/silt slurry that allow the stream it to form its own “natural” transitions and banks.

In addition, we hauled in large amounts of fallen timber and plant material, which we dropped into the streambed and had allowed to flow and lodge themselves in random spots and patterns. Much of the plant material placed along the edges and adjacent to the stream had been removed from the nearby ski slope. Loose stones and large boulders were randomly placed outside the stream’s banks to create smooth transitions to the surrounding meadow.

The majority of the stream flows through the meadow area beneath which the 500,000 water tank is buried. Once basic construction was complete here, the meadow and stream banks were planted using wildflower sod and by hydroseeding with native grass.

CRASHING SUCCESS

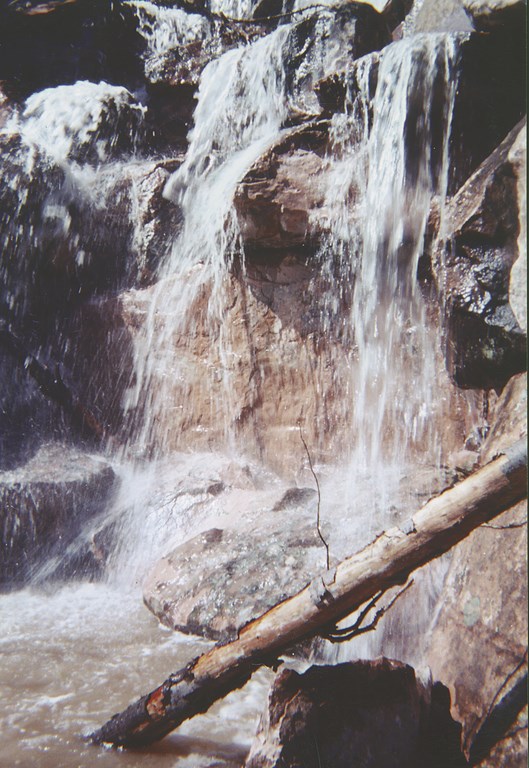

The project’s other great feature was the waterfall.

Set adjacent to the road, the water crashes down to a catch pond, then exits to a catch basin that feeds a culvert system (beneath the road) and then flows down gently to the main pond. The effect is one of driving over a natural stream, and the sounds of cascading and rushing water mask the traffic’s noise while conjuring a distinctly natural mood and ambience for residents and visitors who enter the facility.

|

A Sod Story The guard shack set adjacent to the pond and waterfall is most unusual – and invites quite a rush of visual interest at the entrance to the property. Rustic was the watchword: It looks like something an old trapper might have occupied in the long-gone days before these mountains became the playground of vacationers and skiers. The most unusual thing about the unique structure is the deadfall tree lain across the top. (We’d originally selected an even larger tree but discovered that it had begun to rot.) Rockwork and plantings on its walls, along with the sod and rocks on the roof, completely mask the block structure within. — C.V. |

The waterfall was set up with broad “plateaus” for large rock formations. There are two pools at the top of the waterfall, and they’re set at different elevations to enable us to vary the way that water is introduced to the rock structure. The liner was covered with 40 cubic yards of fiber-reinforced concrete that ranges from four inches to a foot thick.

Using a crane, the majority of the rock was set in three, 12-hour days. All of the large structural boulders were locked in place by gravity. Once in position, we pumped concrete into the spaces behind the rocks to ensure an impermeable substrate that will aid the direction of water flow.

Feathering the edges was the trickiest part of waterfall construction, basically because everything was close enough to the roadway that any flaw would quickly become apparent. We used a combination of small and large rock pieces mixed in with small areas of planted material. As we had done with the stream, we also introduced deadfall timber, gravel and fines to maintain the same sort of natural look.

On the down slope side of the road, the flow from the waterfall emerges from the culverts in a series of gentle cascades that lead to the main pond. There’s a pathway between the sales office and the guard shack, and we set up a 10-by-4-foot stone to create a bridge at one spot along this route.

CONVERGENCE

As has been mentioned at several points, both the stream and waterfall flow into the large pond.

Although it’s a relatively passive component of the plan, the pond is critical to the overall success of the project because of the tremendous sense of tranquility it lends to the environment. It reflects the radiant Utah skies as well as the surrounding forests of pine and aspen while brilliantly mirroring the plantings and flowers that line its banks in spring.

| THE BIG DROP: The waterfall drops 34 feet in a hurry – and the liner was so large and awkward that the only way we could get it in place was to use a crane (left). The moment of truth came after all the boulders had been set and we tested the system for the first time (middle). Once we made some adjustments, the cascade was ready for close-ups (right). |

To complete the natural effect, we created shelves just above and below the waterline that enabled us to set sod and rock material that soften the water’s edge. We deliberately used a light touch in our planting so that shores wouldn’t seem overburdened with plant life – a basic mix of cattails, water lilies, reeds, water celery and a variety of flowering plants and various grasses.

Pulling off so ambitious a project in so compressed a time frame was challenging to say the least, but the results were both gratifying and rewarding – and exactly met the owner’s charge that we were to mimic the natural beauty of White Pine Canyon. In addition, the outcome earned a Grand Award in commercial landscape construction from the Associated Landscape Contractors of America – another point of pride in what stands among our firm’s best work in shaping naturalistic settings.

Clayton M. Varick is a project manager with Land Expressions LLC, a landscape architecture and construction firm based in Mead, Wash. A graduate of Washington State University, Varick grew up in the landscape business and worked for his father’s firm, S. Varick Landscaping, in Seattle. That experience, coupled with his bachelor of science degree in Landscape Architecture, has enabled him to progress quickly at Land Expressions. At 26, he is manager of the company’s Water Division, where attention to detail and dedication to the work have made him a valuable member of the company team.