Hail the Queen

India’s ancient stepwells were about much more than providing their thirsty communities with water. As Victoria Lautman discusses in the second of three articles on these structures, facilities including Rani ki Vav also served both men and women as multi-purpose gathering spots.

India’s ancient stepwells were about much more than providing their thirsty communities with water. As Victoria Lautman discusses in the second of three articles on these structures, facilities including Rani ki Vav also served both men and women as multi-purpose gathering spots.

By Victoria Lautman

Unique to the Indian subcontinent, subterranean stepwells were devised as a response to a dramatic but predictable climate cycle that, especially in the arid western states, guarantees a bone-dry environment for most of the year, followed by weeks of drenching monsoon rains.

Establishing a reliable, year-round supply of fresh water required direct access to the water table. This was a simple proposition in areas where the ground water was close to the surface. But in particularly dry regions like modern-day Gujarat, Rajasthan and Haryana, water could be as much as nine stories underground.

The capricious weather generated extreme fluctuations in the water table, which might dwindle to a trickle for part of the year but become much more forceful in the rainy season. In order to access the precious resource regardless of the season, a well shaft was excavated to connect with the water at its lowest flow.

Next, flights of steps were built adjoining the shaft, allowing access during dry times, and when monsoons arrived, the steps gradually submerged as the water rose, and any descent was significantly shortened. At that point, stepwells doubled as temporary cisterns that retained water as long as possible until the cycle began again.

MULTI-PURPOSE ROOMS

As seen in Chand Baori – the example discussed in the first article in this series (click here) – stepwells were not only sophisticated and efficient water-harvesting structures, but also marvels of architecture, engineering and art. In addition, they performed many functions that went beyond simply providing water to their communities and significantly contributed to local quality of life.

They acted, for example, as cool retreats and shelter from the blistering heat, served as civic centers where the locals could gather. They could be subterranean Hindu temples and shrines or provide water for Muslim ablutions. Stepwells located along remote trade routes offered shelter and rest for caravans and pilgrims and a place for animals to water before the next leg of a journey.

Construction of other architectural sites, such as Emperor Akbar’s 16th-century city, Fatehpur Sikri, are detailed in paintings from that time, showing the same humble, pre-industrial “technology” that would have been used for stepwells and are still seen on construction sites in many parts of India today: oxen, ramps, baskets and sheer manpower.

But building below ground is subject to far greater forces than above-ground structures, and excavating any stepwell must have been dangerous, a constant battle to withstand earth’s thrust on all sides. The number of stepwells that collapsed during construction can never be known, but sinking the well shaft would have been a particularly delicate process.

Professor Kirit Mankodi, an expert on the incomparable Rani ki Vav stepwell (the visual focus of this article), describes a system in which masons were lowered in stages on wooden support rings, surfacing the walls with stone as they descended to the water table. When each level was complete and stabilized, soil was excavated from beneath the rings, which were then lowered to the next level – and so on until the masons reached the groundwater.

The final stage of the constructing the shaft would have been possible only during the driest season: At that point in the process, water was the enemy and had to be bailed out quickly. Logs were packed around the walls and on the floor to prevent seepage while the facing was completed. And all of this, of course, was predicated on the fact that the builders had sufficient knowledge to anticipate the depth of the water table.

THROUGH GENERATIONS

This water wisdom is an important part of India’s technological heritage. The hydrological systems of the early Harappan civilization of the Indus Valley (c. 3300-c. 1700 BC) were among the oldest and most sophisticated on the planet, with ancient settlements showing evidence of drains and wells dating as far back as 2600 BC. (There is also evidence that dowsers were used in siting stepwells. These water diviners performed such services for centuries; as recently as the 1920s, the British colonial government in India employed such a person.)

Geology played an essential part of every stepwell design, which was based on the specific characteristics of each region. For instance, much of Gujarat’s soil is soft, loamy clay, which required a significant shoring-up of walls. This explains the pavilion towers that are characteristic of so many Gujarati stepwells. Consisting of platforms supported by columns, these details may look purely decorative, but they were required to hold the subgrade walls in place. Sandstone blocks, often massive, were hewn to fit perfectly, mortar-free, and reinforced the structures so effectively that many have survived numerous earthquakes without collapsing – a thousand years or more since the first stones were set.

Geology played an essential part of every stepwell design, which was based on the specific characteristics of each region. For instance, much of Gujarat’s soil is soft, loamy clay, which required a significant shoring-up of walls. This explains the pavilion towers that are characteristic of so many Gujarati stepwells. Consisting of platforms supported by columns, these details may look purely decorative, but they were required to hold the subgrade walls in place. Sandstone blocks, often massive, were hewn to fit perfectly, mortar-free, and reinforced the structures so effectively that many have survived numerous earthquakes without collapsing – a thousand years or more since the first stones were set.

By contrast, Delhi’s rockier, quartzite-rich terrain made the elaborate Gujarati interventions superfluous, with the most common construction material being rough-surfaced rubble masonry. The earliest example in the capital city – Gandhak ki Baoli – dates from the 13th Century.

Stepwells were commissioned predominantly by Hindu and Muslim patrons, with both faiths, as mentioned above, requiring the daily use of water. Many of the Hindu wells were subterranean temples, often incorporating mata (meaning “mother”) in their names since, as in many religions, Hinduism equates the life-giving properties of water with fertility and the mother goddess. To this day there are specific water-oriented rituals performed to promote marriage and conception of children.

This accounts for the many “rani” stepwells throughout the country, one of which is the extraordinary Rani ki Vav in Gujarat, which translates into “Queen’s Stepwell.” It is without a doubt the most ornate, costly and grand example ever built, and after nearly a thousand years in obscurity, it is finally getting its due, having recently been designated the new “face” of India’s 100 rupee note. Rani ki Vav even has its own Facebook page.

Commissioned by Queen Udayamati around 1063 to honor her powerful late husband, Bhimdev, this monument, located in the city of Patan, is so outstanding that it was granted UNESCO World Heritage Site status in 2014, one of only 37such sites in India. Given its location an easy hour’s drive from the busy city of Ahmedabad, there’s reasonable hope that architecturally curious visitors will be lured out to see it.

THE RANI’S BEQUEST

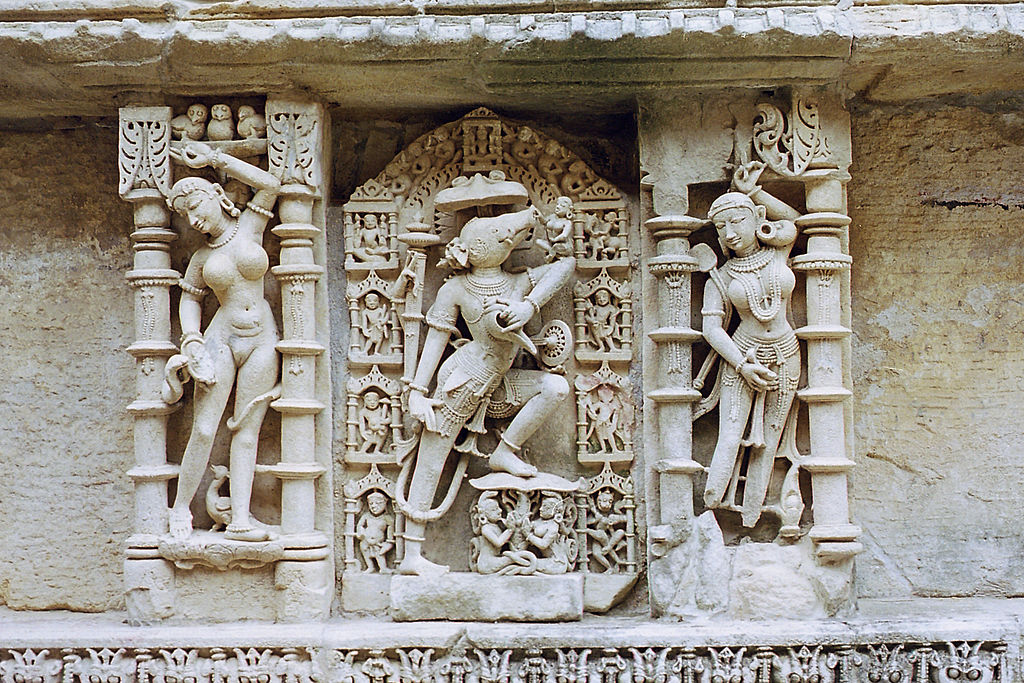

At 210 feet long and 89 feet deep, Rani ki Vav is among the most ambitious stepwell of all in scale alone. It is also the most ornate, incorporating hundreds of sculptures that adorn every surface: Carved deities, consorts, animals and geometric patterns are rendered in astonishing detail and are considered some of the finest work of their era. Udayamati’s labor of love is all the more astounding considering that Patan lacks stone and each block was hauled from a quarry some 87 miles away.

This smaller stepwell may date from the early 19th Century, but the interior space is comprised of columns, pavilions and sculptures almost entirely plundered from the earlier stepwell.

Rani ki Vav is, for the moment, the lone stepwell with a known calamitous history – one that explains the plundering. It is estimated to have taken 15 to 20 years to build, but not long after completion, the stepwell’s water source, the Saraswati River, changed course, swamped the stepwell and caused parts of it to collapse.

| Resource:

For further reading, click here for details on my book, The Vanishing Stepwells of India (Merrell Publishers, London, 2017). — V.L. |

The incomparable achievement gradually filled with mud and silt, so that by the time the British happened upon it in the 19th Century, only part of the well cylinder and some column stumps were visible above ground.

The catastrophe was, in a way, fortunate, since the lower levels were preserved in the process, not unlike Pompeii or Herculaneum. It was not until the Archaeological Survey of India undertook serious conservation work in the 1980s that the full splendor of Rani ki Vav was recognized – and the process of discovery, as you would imagine, was stunning.

Next time, we’ll conclude this three-part series with a detailed look at another stepwell while exploring the legacy of this architectural form.

Victoria Lautman is a Los Angeles-based broadcast journalist, writer and lecturer. Focusing on all forms of art and culture including architecture, design, and literature, she frequently writes and speaks about India. Her book, The Vanishing Stepwells of India, was published by Merrell Publishers (London) in 2017. For more information, visit her website: www.victorialautman.com.