Devils in the Details

Why is it that, on the pool/spa side of the watershaping business, it’s so difficult to find much by way of truly workable plans and specifications?

In residential work, of course, the tone is set by local building inspectors and plan checkers, whose needs seem to vary tremendously from place to place. But that’s no excuse for the fact that the plans used in a great many residential projects are grossly inadequate – especially when compared to the far more detailed and precise plans and specifications required by some of those same building officials for commercial projects.

My point is simple: As watershapes become increasingly complex, I’d argue that those working mostly or entirely in the residential market should strive for something close to the commercial standard when it comes to the documents we draft and use. What depresses me today is knowing, in most cases, that this objective is really nowhere in sight among either contractors or engineers.

My own consciousness on this issue has been raised in recent years because of my role as a design consultant. Knowing that someone else must read, interpret and apply the designs I generate has filled me with an appreciation and understanding of the need for detailed plans and specifications – and this is just as true for my simple backyard pools as it is for the more complex residential and commercial projects in which I get involved.

RISKY BUSINESS

Early in my career as a swimming pool contractor, I’ll readily concede that I used inadequate drawings that left much to be determined on site. Frankly, I was part of the problem on this front, and I am the first to admit I had the wrong mindset.

In the time since, my thinking in this respect has evolved considerably. My personal ambition to work to a higher standard and to increase the sophistication and complexity of what I’ve been able to offer my clients has been a huge motivator. In addition, as the list of places I’ve worked has grown through the years, I’ve been exposed to local authorities and contractors who set very high standards indeed for documentation.

In recent columns, for instance, I’ve mentioned several projects I’m working on in Bermuda. The architects and building officials there require extreme detail. For one project, in fact, I’ve been asked to rework existing plans generated by a local company that knows the local situation well: The plans were deemed inadequate by the architects, and I know for a fact they would be more than passable in many stateside jurisdictions.

And as I mentioned above, this problem isn’t limited to contractors. With the so-called “cookie-cutter” class of swimming pool, for example, engineers seldom do more than work from templates. To be sure, these standardized construction details are not a bad thing if the engineering is reliable and the design truly follows the template. But this one-plan-fits-all approach falls well short of adequate when the design incorporates any deviation from the template. I’ve seen many situations where the upshot of a design wrinkle on a basic pool is a complete lack of any documentation to support that variation.

So the responsibility here is distributed across many shoulders: on those of the engineers who don’t provide high levels of detail, of the inspectors who don’t require it and of the contractors who might not read or understand it if it were there. It doesn’t take much to see potential problems that take root in this situation. Indeed, I think it’s safe to say that this is a big reason that backyard pool projects have spawned so many lawsuits through the years – and why so many pools don’t function properly or fall prey to structural failures.

While I can see how this has all come to pass, I’m shocked by the collective ability of these professionals to let this terrible situation continue.

GOING AWRY

I’m currently involved in a project in Jupiter, Fla., in which it appears that the pool contractor is bound and determined to make trouble for himself by basically ignoring the plans and specifications that came with the job.

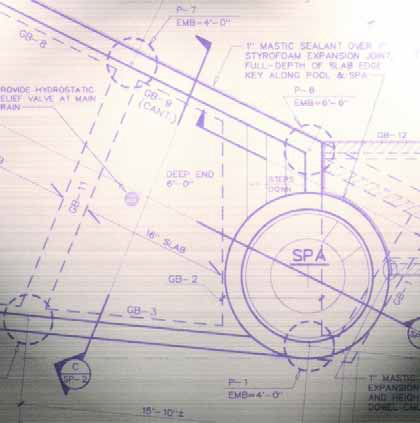

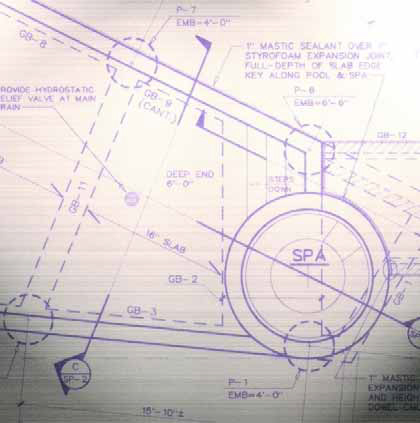

It’s a custom backyard pool I designed and features, among other things, an elevated perimeter-overflow system, remote controls, deck-mounted spray jets, heat pumps and a surge tank with an automatic water-leveling system. I was hired to design the pool and generate a set of conceptual plans and written specifications that were to be used as the basis for project bids.

Given the crucial nature of the edge details in particular, I was very thorough and precise and included isometric drawings of the plumbing scheme with indications of pipe sizes and various other details. I also included specific plan details for the deck-mounted brass jets and cross-sections of the perimeter’s edge treatment. The specifications left little to chance, listing specific equipment selections right down to manufacturers and model numbers. In certain cases, I even listed contact names for technical support.

| The more complex the plumbing scheme, the more important it is for builders to be able to read and understand plans and construction documents. Otherwise, there’s the risk a complicated watershape’s hydraulic system will perform as limply as a tangled bowl of overcooked spaghetti. |

With the remote-control system, I specified not only the system but also the surge protector for the AC power. With the automatic water-leveling system for the surge tank, I detailed the location of the sensors and called out the solenoid used to open the valve that adds water to the tank. I also described how the upper-level sensor would trigger the perimeter-overflow pump when the tank’s water reached a pre-determined level.

In addition, the specifications clearly stated that any deviation from the equipment list or construction details must be pre-approved by the client and the design consultant. It all seemed categorical enough to me.

Unfortunately, the clients selected the low bidder to do the job, and he elected to deliberately ignore or simply failed to read that part of the documentation. I’m not sure why he did so, but I do know that the contractor replaced many specified models with less expensive products and ignored a variety of specifics including the surge protector and the layout of the water-leveling system. The upshot of the equipment substitutions is that the perimeter-overflow system is not functioning properly and that the edge has a number of dry spots.

This builder is probably not going to fare too well when the client compels him to bring the project in compliance with the specifications. If the substitutions he’d made had offered the same performance as the ones specified, no problem. But in failing to communicate about the changes, the contractor stepped right into a sequence of what will prove to be costly assumptions.

Wouldn’t reading the plans before bidding the job have been a better path? I may be an easy-going person, but I really can’t muster much sympathy for such cavalier attitudes.

THE FLIP SIDE

I’m happy to report that such problems do not always arise. In fact, my experience as a design consultant has been that about half the contractors I see are truly interested in doing the right thing and base their pricing closely on the plans and specifications. When these contractors are the successful bidders – which, thank goodness, they often are – the results are very different from those currently unfolding in the scenario just described.

For starters, contractors who conform to the plans and specifications do not expose themselves to the same level of risk as those who try to slide by. Their projects tend to be far more trouble-free – and when there are problems, the issues tend to be more isolated and manageable. And perhaps best of all, conscientious contractors tend also to be open-minded and are able to expand their own bases of knowledge by paying close attention to details that are new to them.

|

Space Relations When an engineer is designing the plumbing layout for a backyard swimming pool, all too often he or she will use standard symbols to indicate equipment locations. The problem is that these equipment icons say nothing about the actual physical space required to house that equipment. Obviously, as projects become more and more complex, equipment pads need to accommodate more than icons and need to be larger than they were even a few years ago. The result on projects with space limitations is that you’ll find equipment areas that are far too small. I ran into this situation recently with an underground equipment room that was grossly undersized – but had already been built. Fortunately, we were able to move some of the equipment into an adjacent sub-grade corridor, so the outcome wasn’t traumatic. Still, this was something that wouldn’t have happened had the engineering plans been as detailed as they should have been – and the equipment room made big enough to hold everything it should have been designed to hold. — B.V.B. |

I’m also, for example, working in north central Florida’s affluent enclave of Lecanto – another upscale project with a long vanishing-edge detail and an overall aesthetic scheme closely integrated with the architecture and interior design of the home.

This is one of those special projects in which there are all sorts of levels of collaboration and interaction among the architect, interior designer, watershape design consultant, watershape contractor and the homeowners. The interior designer, for instance, is interested in the tumbled marble we’re using for the coping; the general contractor is concerned about the drainage on the patio; and the architect, among other things, was involved in integrating the pool with an indoor/outdoor structure called a ramada located at one end of the swimming pool.

It’s a relatively complex project, and the pool contractor has been extremely conscientious from the outset, raising questions before bidding and keeping the lines of communication open through all phases of construction. This level of interaction builds trust and a rapport between designer and builder – qualities of a relationship that can be tremendously significant when unexpected issues arise.

In this case, for example, there was a question about the pool structure relative to the foundation of the ramada, which is located immediately adjacent to one end of the pool. The ramada was built on a perfectly square, heavy-duty foundation (we called it the “elevator shaft”), and the general contractor was convinced that the pool builder should use the near wall of the foundation as a structural wall for the swimming pool itself. Working with the builder, we developed a plan in which we constructed the pool shell inside the foundation of the ramada and expanded the floor of the ramada to encompass the pool’s wall. This kept the pool structurally separate from the ramada – without compromising their visual integration.

These decisions and others all required interaction among the general contractor, the pool builder and me. Had this particular pool builder taken the less careful approach of the gentleman I described above, who knows where this project would be right now?

ALWAYS EVOLVING

As I continue to learn and grow as a designer, the documentation I provide tends to offer greater and greater amounts of information and levels of detail. I find myself including more information on components such as conduits and electrical boxes for control systems or lighting, for example, or specific recommendations for plumbing configurations that support waterfeatures or water-in-transit effects. And my plans include ever more precise instructions about aesthetics, including materials selections.

My point in all of this is not to deride those who are doing things in a less strenuous way, but rather to highlight the value and importance of pursuing and adhering to high standards when it comes to plans and specifications – even in localities where building officials don’t require it. The benefits of doing so will pay dividends in reduced hassles, greater customer satisfaction and in your ability to control the devilish details that can make all the difference in determining the success of a project.

Brian Van Bower runs Aquatic Consultants, a design firm based in Miami, Fla., and is a co-founder of the Genesis 3 Design Group; dedicated to top-of-the-line performance in aquatic design and construction, this organization conducts schools for like-minded pool designers and builders. He can be reached at bvanbower@aol.com.