Crime at the Gate

Plagiarism. Copyright infringement. Theft of intellectual property. We hear and read about these crimes in the media all the time and don’t think they’ll ever affect us. But I can bear witness to the fact that we have people in our midst who seem to think that committing these crimes is no big deal.

Setting aside any other criticism I’ve ever lain at the feet of the watershaping trades, if there’s one intolerable problem the industry has, it’s that there are people within it who are apparently willing to steal to get ahead.

I’m not talking about job-site incidents where materials or tools mysteriously vanish. That’s a real problem, but even more damaging in my eyes is the surprisingly common practice that some people have of representing the efforts of others as their own. In a phrase, I’m talking about the misappropriation of design work.

I know I’m not alone as a victim of this phenomenon. In fact, I personally know of far too many situations in which low-rent operators have represented the work of superior designers and builders as their own – and I want to use the privilege of this column to make a case for stringing these people up by their proverbial thumbs.

SHOE SIZE

Obviously, we’re talking about a relatively small number of people who do some very bad things. The discussion I’m offering here is a cautionary tale for those who would dare sink so low, but my far more important desire is to inform those who might find themselves being victimized by this unscrupulous practice.

If you’re among those who’ve done this, accept the fact that decorum prevents me from expressing my full and utter contempt for you. If your foot fits into that particular shoe, you’re lucky to be in business – and your only path to legitimacy is to stop your criminal behavior right now. (It would also be appropriate for you to offer an apology and reparations to those from whom you’ve stolen, but that’s probably asking too much of someone of such weak character.)

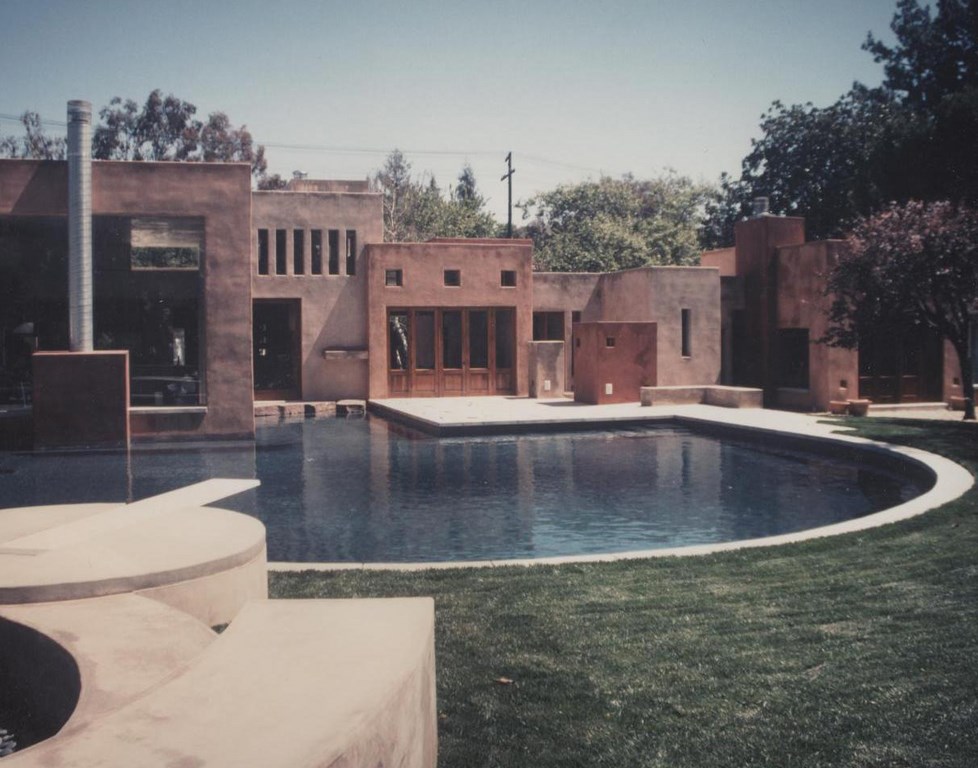

| The images scattered throughout this column are among the projects of mine that have been lifted and used in someone else’s website. They include work previously published as being mine in WaterShapes and elsewhere — and a California project with which the perpetrator had absolutely no possible connection on any level. |

If you’re among those who have been hit by this crime, I want you to understand that you have more power than you might think to set things straight and that you do not need to stomach such violations with quiet resignation: There are legal remedies.

To be sure, every situation is different and it is seldom easy to interpret the legal issues. As a result, the first and most reliable advice I can offer is that you seek legal counsel if you think your control and ownership of your design work has been violated. And do so quickly: Failing to act promptly can, in some cases, compromise your claim to intellectual property rights.

I’m fighting mad about this because I’ve just fallen prey to one of these turkeys. I won’t name names, but this one case may well be the straw that breaks the camel’s back for me and drives me to seek legal restitution.

To this point, I’ve been inclined to laugh these incidents off, probably because the first time I ran into this problem it was really sort of funny. It happened about eight years ago, while I was on site to supervise the construction of one of my projects. A guy walked onto the site with a camera, walked up to the first person he saw and announced that he was a friend of David Tisherman’s and had been asked to come and take some photographs for him.

Unfortunately for this particular prevaricator, I was the person he approached that morning. I had never seen this mutt before in my life, and I knew I hadn’t asked anyone to take pictures on my behalf. I was left speechless for a few moments before informing him that he was speaking to his “mark.” Let’s just say I dispatched him with a clear and immediate suggestion that he remove his person from the property lest he wanted to face charges of trespassing.

HIGHWAY ROBBERY

I’m not sure exactly what was going on with that situation, and I’ve always found its ironies to be amusing. But the more recent incident referred to just above is far more serious and I’m far less inclined to be easygoing this time around.

Here are the facts: A pool builder who operates in my east-coast market area recently posted several photos of my work on his website, claiming by implication if not in fact that they were all his projects. In no cases were these projects in which multiple players had roles and anyone might therefore make an exaggerated claim of credit. (That’s a form of ethical distortion I might be able to tolerate in an isolated incident, but not in this case.)

In my work, as any long-time reader of these columns knows well, I build everything I design, and this joker had nothing at all to do with any of the projects he was claiming as his own. Furthermore, his web site claimed that I personally mentored him for a period of years, even though I’ve never worked directly with him on any sort of professional level. What truly galls me is that some of the images he “borrowed” were projects in California, a continent away from his own meager work.

The fact that someone would so publicly engage in such a bald-faced set of lies is genuinely astonishing. At this writing, the offending web site is up and running, but I am confidant that by the time these words make it to print that the situation will have changed. Somewhere in the interval, in other words, he will doubtless become intimately acquainted with my attorney.

The fact that someone would so publicly engage in such a bald-faced set of lies is genuinely astonishing. At this writing, the offending web site is up and running, but I am confidant that by the time these words make it to print that the situation will have changed. Somewhere in the interval, in other words, he will doubtless become intimately acquainted with my attorney.

An incident like this brings up several points that go well beyond the particulars of my own situation. First of all, everyone needs to recognize that, in this day and age, it’s relatively easy to misappropriate intellectual property. Between the Internet, digital photography, graphic-design software, e-mail, cell-phone cameras and other modern gizmos, access to information and images is easy enough that it’s simple to perpetrate false claims of all sorts.

Second and more important, all reputable watershaping practitioners need to understand the basics of copyright law and their rights when it comes to their intellectual property.

It’s well established that copyright protection indeed extends to people who design things. Again, the laws are complex and each situation is different, but as a rule you can safely assume that if you create an original design, you own the copyright on that design. Among other things, this means that other people cannot rightfully lay claim to your work.

People who cross that line are not only unethical, but they’re also violating the trust of their clients, violating your rights, tainting your reputation and perhaps (in extreme cases) exposing you to legal action. Ultimately, these clowns also degrade the reputation of the industry as a whole – plain bad actors all the way around.

CLEAR AIR

The bad actions of outright thieves are symptomatic, I think, of a more general problem that nibbles at the edges of the dignity of the watershaping industry. For want of a better term, we might call it a “fog of dishonesty,” a vapor that carries an odor with it that taints our businesses in all sorts of milder ways.

For many years, for example, it has struck me that many people in this industry do not give proper credit to those who have influenced them in their work. To be sure, this is a subtle form of dishonesty and might reflect a general lack of sophistication more than it does any sort of criminal intent.

It’s my observation that reputable, credible design professionals fully credit the work of other people who have influenced their own efforts. In our industry, by contrast, we have players who openly, willingly, eagerly take credit for innovations they didn’t create for the sake of self-promotion.

This is very different from the worlds of architecture, landscape architecture and the fine arts, where designers, artists and craftspeople routinely detail the pedigrees of their work. Just think of the legions of architects who cite Frank Lloyd Wright as their spiritual forbear, for example, or who avow their dedication to the principles of Walter Gropius, John Lautner or Ricardo Legorreta.

This is very different from the worlds of architecture, landscape architecture and the fine arts, where designers, artists and craftspeople routinely detail the pedigrees of their work. Just think of the legions of architects who cite Frank Lloyd Wright as their spiritual forbear, for example, or who avow their dedication to the principles of Walter Gropius, John Lautner or Ricardo Legorreta.

I acknowledge that failing to cite design influences is not dishonesty on the same level as representing work you didn’t do as your own, but in very real ways it’s on the same continuum of moral and ethical compromises – and is, I would argue, something that we easily can and should change.

Look at it this way: When I create a design that is influenced by an architect and designer as brilliant as Luis Barragan, this is something I want my clients and other people to know because it’s part of the beauty, interest and appeal of the project. Clients are often turned on by the thought that their watershape is part of a full-fledged design tradition. And later on, when they see a Barragan design in print or in person, they’ll be even more appreciative of the genius who influenced their own project.

The great designers who influence us deserve both credit and respect for ideas that live on through their work and the works of others. For me, it’s not so much a matter of feeling an obligation to be forthcoming with such information (which I do); rather, it’s really all about the excitement of interpreting the works of a John Lautner, Fred Briggs, Ed Niles, Frank Lloyd Wright – or the architect of Hadrian’s Palace, who showed me the value of raising the bond beams of watershapes.

This appropriate sort of attribution never detracts from the appeal of my work; instead, it elevates and dignifies it. It also confers credit upon me by way of association – the irony here being that truthfulness about design influence allows you to achieve the sort of credibility the thieving pretender is trying to steal.

JOKES BY DESIGN

One difficulty in combating plagiarism and theft of intellectual property in the watershaping trades has to do with the fact that the designer’s work is not recognized in our industry the same way it is in others.

This is particularly true in the pool/spa industry, where “design” was something salespeople did to sell projects and only in recent years has there been any discussion of what we do as potentially being works of art. This leads us directly to ongoing discussions about design education within in the industry, but for now let’s stay directly on the topic of honesty and credibility.

The pool industry’s lack of respect for the role of design shines through with brilliant clarity in the structure of the “design” awards programs that have proliferated through the years.

I perceive this as another haze of dishonesty that should burn everyone’s eyes. I personally know of a situation in which a subcontractor who installed the plumbing on a project and had something to do with a portion of the structure submitted photos of the finished work to an awards program with the implicit claim that he’d been the designer.

The subcontractor violated no contest rules, so what’s the problem? In fact, most award programs in our industry require only a fee, a photograph and a brief project description – that’s it. In this setting, the word “design” is mere window dressing anyway. No proof is even required that the client was happy with the job, that it was built properly or that it is still even functional.

The subcontractor violated no contest rules, so what’s the problem? In fact, most award programs in our industry require only a fee, a photograph and a brief project description – that’s it. In this setting, the word “design” is mere window dressing anyway. No proof is even required that the client was happy with the job, that it was built properly or that it is still even functional.

What’s wrong with this picture is that a builder or even a subcontractor can take someone else’s design, screw it up completely in the construction process, alienate the client – and then take a nice photo and win an award. This is credible?

I accept the fact that design awards are all about marketing, and far be it from me to suggest that people shouldn’t promote their achievements, but let’s at least be honest about this. How hard would it be to require, as a part of a design-award submissions, signed statements from clients declaring that they’re satisfied with the projects? How about asking for before, during and after photos of construction, a set of plans and a signed statement indicating who deserves credit for the design?

None of that seems like too much to ask. And without that sort of credibility, isn’t using these awards for marketing purposes the moral equivalent of pulling the wool over a clients’ eyes?

Again, one might argue that what goes on with the loose rules of design awards is a far cry from deliberate misrepresentation. For me, however, it’s all pretty much on the same continuum. Although it seems less harmful than other forms of dishonesty, it’s still a compromise that saps the dignity and credibility of the pool/spa industry.

THE GLOW

One of the joys of working as a designer is that you have a sense of creating something that has never been seen before. Yes, there’s a satisfaction of ego that’s involved, even a vanity that comes with working as a designer or artist. But far beyond ego or vanity is an even greater sense of satisfaction that comes from putting part of yourself into the work you do for other people.

Design is different from construction in that the designer is the one who is charged with using his or her background to create a set of plans that fuses the desires of the clients, the extent of the budget and the requirements of the site in a way that is creative and appealing.

Those who execute the plans may well feel pride and take credit for their role in a project, but they are not its designers. They nonetheless deserve whatever credit is due, which is why I’m always eager to mention the subcontractors, craftspeople and suppliers who play key roles in my projects. Good work should always be recognized and rewarded in this way. Likewise, if my design stems directly from the work of an architect or landscape architect, it’s my opinion that I am morally, ethically, professionally and legally obliged to place credit where it’s due.

Those of us who design watershapes, landscapes, buildings, automobiles, furniture, kitchens, clothing and countless other things are in the business of bringing both utility and beauty to people’s lives. We have the privilege of being in the business of making people happy – to me a sacred trust that should not be abused by the lies of smaller minds.

I was taught that to reach high places, you have to follow a high road. If you aspire to be a great designer, lying about it along the way is no short cut to achieving professional stature. Not only is it wrong and foolish, but it’s also ultimately bad for business.

David Tisherman is the principal in two design/construction firms: David Tisherman’s Visuals of Manhattan Beach, Calif., and Liquid Design of Cherry Hill, N.J. He can be reached at tisherman@verizon.net. He is also an instructor for Artistic Resources & Training (ART); for information on ART’s classes, visit www.theartofwater.com.