Coming to Terms

It’s true for any subject that it’s basically impossible to teach and learn about a topic unless there’s a shared set of terms that everyone understands and can agree about what they mean. I’ve thought about that fact a lot in developing a course for university students about watershaping, or what I’m most often calling “water architecture” these days.

With watershaping as a subject, that sounds simple enough. After all, we all know the meaning of “swimming pool,” “fountain” and “pond.” Or do we?

I’m not so sure anymore. When I started breaking down our vocabulary for classroom use, I quickly recognized that the meanings of the words we use are anything but clear. Indeed, the more I dug into this seemingly simple phase of curriculum development, the murkier things became.

The difficulty I ran into was this: Once I moved past the most rudimentary sets of terms and definitions and looked closely at the language we use to describe what we produce, it became painfully obvious to me that

our industry has been moving along for years without any clear, unambiguous descriptors.

To show what I mean, let’s look at some of our most commonly used terms and pull them apart under the light of the vast variability they encompass. In doing so, I hope to shed a broader light on a subliminal challenge that faces us whenever we choose to call a system by one term or another.

MATTERS OF LIABILITY

In all my years of creating a broad range of watershapes, I’ve come to see that if there’s one area in which terms matter the most, it has to do with how a given vessel reflects the level of legal and financial liability incurred in designing and constructing it.

Consider, for example, the terms “residential” and “commercial” – words so commonly used and presumably so well understood that we rarely give them a second thought. But when you step back and consider those terms in the context of code requirements they carry with them, the scene becomes almost instantly murky.

We know as a rule that “residential” installations are licensed and inspected by local building departments; similarly, we expect health departments to regulate “commercial” installations. Certainly, codes vary from place to place, but overall (in terms of definitions, anyway), everything seems clear enough – until, that is, you factor in the variations of system types and locations as they crop up in the real world.

Here’s a simple example of this phenomenon: Our firm recently performed design work on a small fountain that fronts high-density, residential loft properties on a busy street. It’s inside the property line, but there is no barrier between the vessel and pedestrians walking by on the sidewalk. It’s technically “residential” and is less than 18 inches deep, so this system doesn’t need to meet health department standards, and I suppose most people would say that’s lucky for us. Plus, it’s a fountain and is not intended for human contact.

No problems here, right?

Well, in this case at least, I would argue that relying on the basic meaning of terms would be foolish in the extreme. The fact is that just about every public fountain ever built at some point becomes “interactive” (another loaded term I’ll tackle below) because there are always going to be people who will get into them, whether it’s teenagers who enjoy challenging social boundaries or small children who just don’t know any better. In other words, I know as a matter of reality that the John Q. Public is going to come in contact with the water in this so-called “residential” installation.

I know as well that if someone gets injured or sick from exposure to unclean water in this fountain, there’s a high probability that the designers, builders and service technicians will be hailed into court right alongside the homeowners and the homeowners’ association. This is everyone’s issue!

Committed to avoiding that fate and based on experience, we designed our system with elements common to commercial swimming pools in so far as turnover rate and chemical treatment were concerned. And we did so despite the fact that neither the city nor the health department defined this installation as “public” or “commercial” because of zoning and the location of the property lines.

BREAKING DOWN

In just this one small example, we can see how the terms “residential,” “commercial,” and, in this case, even the word “fountain” have absolutely no bearing on the realities of the situation. Setting aside the fact that most fountains reside in an enormously gray area when it comes to regulations and liability, in this case we can’t even be clear about what is and isn’t “residential” with respect to design standards.

In other words, these terms are defined by their situations and, in fact, have very little objective meaning.

Some might argue that a situation such as the one I described are not normal and that we can, in good faith, continue to rely on the terms “commercial” and “residential” in describing what we do. I’ll buy into the idea that when it comes to backyard pools and we can make a reasonable assumption that the word “residential” does actually work in a majority of cases. A basic definition here might be something like “a body of water located on a privately owned property where access is controlled by the owner and use is limited to the immediate family and close friends.”

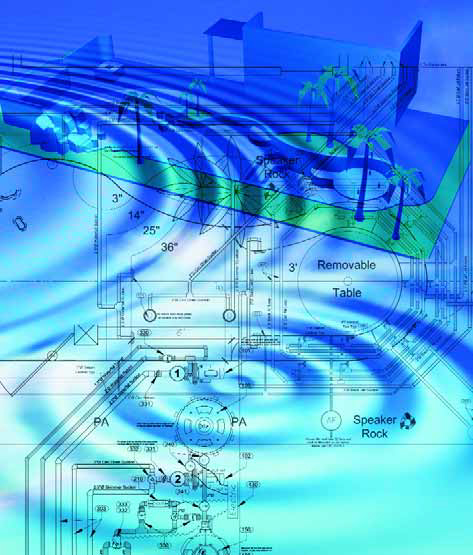

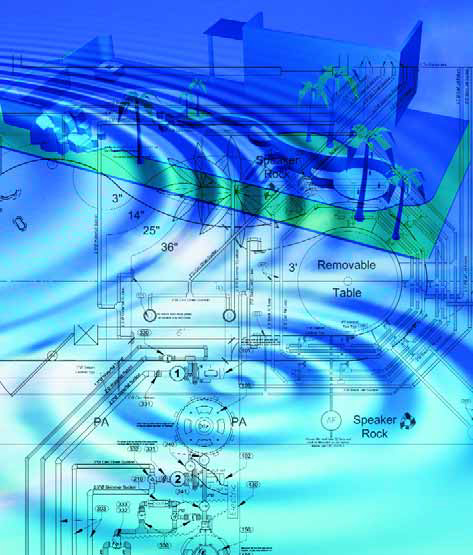

| With several types of watershapes, the lines between ‘residential’ and ‘commercial’ are sometimes blurred according to placement and probable use (or misuse). By code, for example, fountains of less than 18 inches in depth can be built with only marginal sanitizing and filtration systems (or none at all). But the fact of the matter is that people will come in contact with the water, which leads some of us to meet or beat the pool codes when it comes to making these bodies of water safe for non-approved bathers. |

That works up a point, but consider the ramifications of that narrow meaning when a backyard pool is used as a site for private swimming lessons. In such a situation, dozens of people (maybe more?) might be using a small, residential-scale pool in a manifestly “commercial” way. I would argue from a simple liability perspective that such an application falls under the umbrella of commercial rather than residential construction.

Granted, that’s a heretical notion: Nobody wants health departments to get involved in regulating backyard pools or have anything to say about people conducting swimming lessons at home. Yet in such situations, one could reasonably argue that by virtue of usage, such pools are, in fact, “commercial” by definition as they are a means of making money.

The same is true of extremely high-end “residential” installations where wildly wealthy or famous owners routinely host parties for hundreds of people. In those circumstances, the same issues apply: The work may be officially “residential,” but in terms of liability exposure, you’d better think “commercial” or you’ll be exposing yourself in genuinely frightening ways.

When it comes to the challenge of teaching landscape architecture students how to use these terms, I’m pushing the idea that although there are some basic definitions in use, it’s the application that unfortunately sets the standard, not an official definition around which all watershapers could rally.

COMMERCIAL TERMS

Let’s briefly take this discussion of “commercial” versus “residential” in yet another direction in which we’ll see another spasm of imprecision: Consider for a moment the manufacturers of pumps, filters and other basic circulation components who classify their wares as being either commercial or residential. They do this for obvious marketing purposes, and the distinctions are based more or less on the volumes of water given components are capable of handling instead of on the specifics of an application.

The problem in the real world is that there are always going to be residential installations large enough that they will use so-called “commercial” equipment and just as many small commercial installations that will use “residential” components. So even when it comes down to specifying circulation components, the terms quickly lose any certainty of meaning.

With all that in mind, I’ve come to believe the term “commercial” should actually be retired. If defining a “residential” installation is subject to varying circumstances (as in my street-side fountain), the spectrum of “commercial” pools is so broad that the term becomes completely and utterly worthless.

| Often, watershape-related definitions are dictated by regulations. Health departments, for example, require safety signage, access to emergency telephones and the specification of maximum bather occupancy for public, commercial and community pools and spas. But are bathers any less safe in residential pools without these items? |

Of course, elimination of the term is impractical because it’s in such wide use. So, undaunted, I came up with a definition for a commercial watershape installation that says, “A body of water that will be used in some way by the public for the owner’s economic gain.”

As with the residential definition, the above sounds pretty good – until, that is, you consider settings such as private health clubs or exclusive resort properties or condominium developments. In all those situations, access to the water is supposed to be monitored and controlled by property owners or homeowners’ associations. Those places are anything but public, in other words, but referring to them as “commercial” says absolutely nothing with respect to bather load or actual usage.

Yes, they’ll be regulated by health departments in most cases, but to me, that single factor should not be the sole determinant when it comes to categorizing installations within our industry. It’s the usage to which these vessels are put (rather than any official designation) that determines liability and/or the nature of system design.

It gets worse: These days, I sometimes hear the terms “semi-commercial” or “semi-public” used to describe specific watershapes, and I suppose in the context of projects that are on private properties owned by companies rather than individuals there’s some sense to those terms. In application and usage, however, they mean next to nothing.

PUBLIC AND INSTITUTIONAL

Adding spice to the discussion is the wonderfully slippery use of the word “institutional,” which to some people means an installation that exists on a property such as a college campus. I would argue instead that institutional pools are those for which standards (typically dimensional and performance-related) are set by organizations other than building or health departments – mainly the plethora of organizations that deal with pools designed for competition.

The nuances of requirements set forth by organizations such as the International Olympic Committee, U.S. Olympics and others are beyond my concern here – other than that they help me illustrate the fact that projects designed to meet those standards exist in all sorts of settings and have a range of owners, from schools to municipalities and even the federal government.

| Nobody wants public agencies to get involved where they aren’t already, but it might be argued that there are certain high-use residential projects in which following the authorities’ regulated tread and riser dimensions for steps and even including stainless steel handrails and ladders might make sense from a liability standpoint – another point at which conventional ‘definitions’ simply aren’t adequate. |

In considering this term, is a pool at a dormitory on a college campus that’s meant strictly for recreational use by students called “institutional,” “semi-commercial” or “public”? I suppose it could be any or all of those things depending on how you look at it. But what if it’s a really small pool at a tiny private school owned by a church? Then I suppose you could say it’s “a commercial pool owned and operated by a private institution in a semi-public setting built using residential equipment but regulated by the local health department – maybe.”

When you break things down to that level, the usefulness of the terminology is a laugh-out-loud proposition – except for the fact that when we consider the potential of watershaping as a distinct subject being taught as part of an accredited university program, it becomes plain that, as an industry, even the best among us can’t be absolutely certain of what we mean when we use these common terms.

In the real world, this leaves us to use words tied to settings and intended uses – but even then you’re left with the fact that a number of terms in common usage simply do not work adequately.

To drive that point home, here’s one more brain-twister: What do you call a pool built for therapeutic purposes at a non-profit facility for handicapped people? Is it “commercial” or “semi-commercial”? Well, not by any convenient definition I know. Is it “institutional”? Maybe. Is it something else that hasn’t appeared often enough to have attracted a specialized descriptive term? Almost certainly – and I can hardly wait to add that one to my list.

GOING INTERACTIVE

Let’s take this discussion in yet another quirky direction and consider the terms “interactive” and “decorative.” Although they have no official or formal meaning, it would seem natural to say that an “interactive” body of water is one that is designed for human contact and that a “decorative” body of water exists purely for aesthetic enjoyment.

As with the more objective terms discussed above, on a rudimentary level “interactive” and “decorative” both make sense. But once again, as soon as you apply pressure and ultimately break them down in terms of applications related to how these words are actually used, you enter another terminological funhouse.

In fact, all swimming pools and spas could be said to be functionally “interactive.” In fact, they could be said to be the most interactive of all watershapes because they’re designed for complete bodily immersion. Yet when we say “interactive,” that’s not what anyone is referring to: Instead, we use the term to impute that a system provides some form of human contact with water by a means other than immersion.

| Some health department rules might actually be helpful for much-used backyard pools. In lots of cases, for example, regulations require showers around pools as well as restrooms and drinking fountains – all in quantities tied to the surface area of bather-accessible water in a given area. These items are never required on residential pools, but that fact alone doesn’t make them bad ideas. The same goes for filtration systems: In many areas, we must create ‘dry wells’ for discharging backwash water so it ends up replenishing subterranean aquifers. Does it necessary make sense to set up residential systems so all that water is sent into the municipal sewer network? |

Some water-oriented theme parks are probably the readiest examples of “interactive” facilities, along with the now-familiar leaping-jet fountains and settings that have so-called “splash pads” that might themselves be defined as areas that have waterpark-like features without being located in actual waterparks.

In this context, we also could say that slides and diving boards are “interactive” elements when they’re part of swimming pools, even though those elements are seldom considered “interactive” in common industry vernacular. On the other end of the spectrum, a hydrotherapy spa in a hospital facility is distinctly and intimately “interactive,” but I’ve never heard one described that way.

Finally, of course, there’s the example I used at the top of this discussion – that is, the unintentionally “interactive” body of water – a catch-all phrase that could be attached to just about every fountain that has ever been built. (For that matter, if there’s a watershape that’s ever been made that isn’t touched by a human being at some point, I’ve yet to see it.)

It is with watershapes described as “decorative” that we come about as close as we ever will to a definition with clarity. I define a these installations as any vessel meant to have visual appeal – the one problem there being that, while every backyard pool is meant to look good, some of them clearly do not.

And so, even where we might expect some relief, we get caught in yet another loop of imprecision and amazing verbal inadequacy.

MAKING SENSE

So what does the word “decorative” really mean in the world of watershaping?

Well, we can comfortably assert that competition pools aren’t decorative because that’s not their primary purpose, but these days, most of these projects include quite advanced aesthetic programs. I suppose we might stipulate that pools meant for training Navy Seals or astronauts are not “decorative,” but such watershapes are so rare that it’s hard to base any kind of definition on them.

Conversely, koi ponds, lakes and lots of ponds and streams can be comfortably defined as purely “decorative.” Yet as we know, these days a great many of these watershapes are also intended for human contact or even swimming. And, honestly, I don’t know whether touching the water to feed a beautiful fish qualifies as “interactivity” or not. If I had to decide one way or the other, I probably would say yes, that counts as interactivity – but don’t chemically treat the water the way you would a typical “interactive” body of water unless you want to kill the fish!

Again, we find ourselves left with terms that really don’t stand up to scrutiny when considered in light of either common usage or real-world applications.

| In lots of cases, equipment sets for public pools are located indoors, both for aesthetics and noise control. This confronts the eager minds of my students with a simple question: Doesn’t it seem odd that in the residential realm, where there is generally a higher standard set for both aesthetics and bother-free performance, that neither aesthetics nor noise are considered in the common practice of placing residential equipment sets out in the open in side yards? |

What’s sort of intimidating about this entire discussion is that the terms we’re talking about here are the ones that actually have the clearest definitions. Our lexicon gets absurdly imprecise, for example, when we talk about distinctions between, for example, “steps” and “benches.”

There’s more: What’s the difference between a “waterfall” and a “cascade”? Is a spa’s “spillover” a type of “waterfall”? By what definition does a “pond” become a “reflecting pond”? Where do we draw the line between “architectural” and “naturalistic”? Do we define a pool with a brimming water level as a “perimeter-overflow,” “slot overflow” or “deck-level” system? Is there any difference between a “beach entrance” and a “zero-depth entrance”? What constitutes the “shallow end” as opposed to a “deep end”? What do we mean when we say “hot tub” or “spa”?

And, finally, what the hell is a “waterfeature?”

I won’t belabor this point any longer because the discussion could become utterly ridiculous (if it hasn’t gotten there already). The problem is that it would be easy to dismiss the whole matter, except for the fact that as an industry we use these words every day to communicate with clients about what they’re buying and with regulators and other professionals around whom we’re designing and building.

BEYOND HUMOR

When I stand up in front of my students and try to make sense out of the mass of terminology we currently endure, the challenge, ironically I suppose, is much more than a mere academic exercise. These young people are in their chairs because of a genuine interest in pursuing this field of endeavor, and they’re looking to me as a distinguished representative of our industry to say what I mean and mean what I say.

Beyond mining the rich comic potential of the subject here, all I can say is that I’m going to keep trying and, I hope, will someday succeed in provoking this magazine or some industry entity into coming up with a set of terms that will stand up in the face of the permutations and combinations of the watershapes we produce. So far, however, I must report that I’ve yet to run into anything that’s even approximately definitive, let alone authoritative enough to be persuasive.

Until we do come up with some sort of working vocabulary, I believe the best we’ll be able to do is consider the application first, then attach the terms that fit the best. If we can’t fly to the moon, at least we should put the horse in front of the cart.

Mark Holden is a landscape architect, pool contractor and teacher who owns and operates Holdenwater, a design/build/consulting firm based in Fullerton, Calif., and is founder of Artistic Resources & Training, a school for watershape designers and builders. He may be reached via e-mail at mark@waterarchitecture.com.