Images in Motion

Ever since the hydraulic principles of ancient Persia were ‘rediscovered’ by Europeans during the Renaissance, the sky has literally been the limit for watershape designers. At the 17th-century Dutch Palace of Het Loo, for example, fountain jets that trace their developmental history at least as far back as 8th-century Persia make an emphatic statement about the power of those who commissioned them.

We all marvel, and rightly so, at the waterfeatures of Renaissance Italy, the pools of Versailles in France, the fountains of the Peterhoff in Russia and at dozens of other spectacular watershapes that have been created in Europe, Asia and the Americas in the last several centuries.

Where did most of the inspiration for these watershapes originate? As we explored in the first article in this series (“Images in Time,” October 1999, page 26), most of today’s aquatic designs can trace their origins to far older sources in the Greco-Roman tradition and, much more clearly in the case of moving water, to the work of Islamic designers and hydraulic engineers.

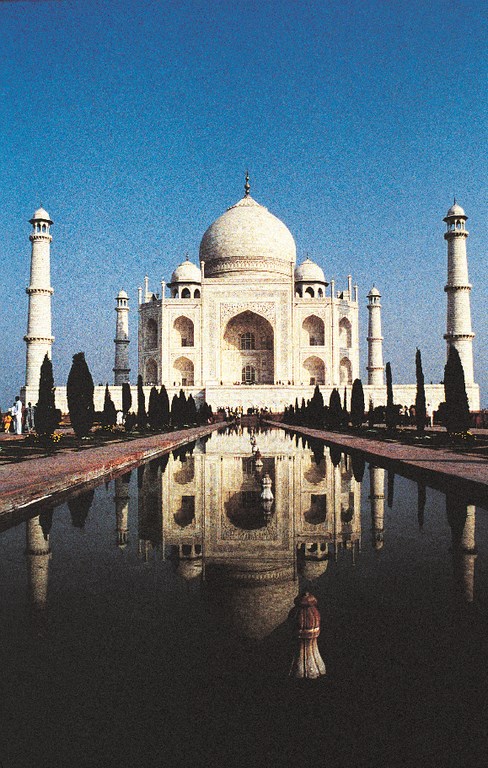

As we saw last time, Greek and Roman models defined proportions and decorative styles that carry straight through two millennia to the pools at Hearst Castle and the aquatic complex at Bellagio. We also dipped slightly into Islamic traditions as expressed through the Taj Mahal and the waterfeatures of Moorish Spain.

This time, we’ll dive more deeply into the Islamic origins of contemporary design, exploring the keys to their design principles and, more important, looking at the ways in which their experimentation with hydraulics was used by designers during the Renaissance and has reached all the way into modern watershaping technology.

AT THE SOURCE

The achievements of Islamic engineers certainly have their roots in earlier work in the ancient Middle East, but nothing remains today of the legendary Hanging Gardens of Babylon or of any of the waterworks that turned the region on the banks of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers into the Fertile Crescent and the cradle of modern civilization.

| The Court of the Canal at Generalife (left) is among the many watershapes of Moorish Spain that inspired designers and hydraulic engineers of Renaissance Europe. Prominent here is the use of water to organize outdoor spaces as quadrants – and the use of water jets to humidify and cool the surrounding air. Also in Moorish Spain, the Court of the Lions at the Alhambra (middle) is remarkable for the fact that the water is there at all. Dissecting the engineering involved in bringing water to this hilltop fort led to discoveries that drove aquatic design in Europe for hundreds of years. The Taj Mahal (right) is perhaps the most famous Indian application of Islamic principles of hydraulic engineering – a practical feat more than matched for most onlookers by the sheer beauty of the space and the use of reflections to enhance the otherworldly quality of the tomb’s architecture. |

There can be little doubt that the arid climate forced local cultures to get creative in harnessing water for irrigation. And given what we see in later Islamic culture, it’s also a fair bet that earlier Mesopotamian, Sumerian, Assyrian and Persian designers also knew a trick or two when it came to using the flow of water and the effects of evaporation to humidify and cool the air in both public and private spaces.

|

Moving Waters The principal hydraulic difference between a body of water at rest and one in motion is gravity. In that sense, watershapers are manipulating the influence of gravity upon this fluid in order to create effects that stimulate the senses, produce energy or purify the water for various purposes. Setting aside practical considerations such as energy production or water purification, we humans find great emotional satisfaction in what can best be described as “The Splash” – an effect of gravity that has several components: sight and the manipulation of light, sound and its capacity to resonate through our bodies, and touch or feel, with its full range of environmental effects. With these three important sensory influences as a guide, we have developed diverse ways to disturb the flow of water and stimulate onlookers. [ ] Sight. As light intersects water, it does two things. First, it partially reflects off the surface of the water and enters our eye. Second, it enters the water and is bounced around within the fluid (refracted), only later making its way out again to travel to the viewer. When the second effect occurs, we see the “jelly-like” nature that water seems to have – an effect that alters our perception of immersed objects or objects set behind a veil of water. The combination of reflection and refraction, along with the prismatic effects the water has on color perception, create the magic that we see in every watershape and its movements. [ ] Sound. If you have any doubt of the ability of the sound of water to move us, go to a record shop and check out the countless recordings of the sounds of streams, fountains and oceans. Water indeed has a profound psychological effect upon our emotions and spirits; it soothes the savage breast in all of us. As important, those sounds and sensations can be altered by the designer to change the psychological effect. The basic sound we hear, by the way, is not of water itself but of the various reactions water has to materials it intersects and contacts. When it hits a piece of metal (as opposed to masonry), it can produce a higher pitched sound and thus excite our senses. By contrast, only soothing sounds seem to come from water entering itself: Awareness and manipulation of this deep, pure sound is a factor in the success of almost all watershapes throughout history. [ ] Feel. The last in this triad of effects has to do with the way water changes the general climatic conditions within its surroundings. It has a tendency to alter the atmosphere around it to be more like itself, which typically means cooler and more humid. For ancient Islamic designers in their arid environments, this single factor could dramatically alter peoples’ states of comfort. Where water is scarce and temperatures are high, the environmental changes that water brings can be the prime reason for its ornamental use. When we as designers decide to alter the course of water in any way, we engage in changing the environment and climatic conditions. The more we alter it – that is, the smaller the “pieces” of water we make, the greater their potential to influence the environment by changing humidity and temperature. Awareness of how all this works is a prime asset to watershapers, and has been for thousands of years. When we want to create a place that captivates and stimulates people on a hot day, we do our part best by creating conditions that influence their emotions and responses. – M.H. |

We can only speculate that hydraulics was a refined science before the rise of Islam in the 7th Century AD, but we’re certain that by the time the Islamic culture began spreading east and west toward the end of the first millennium, its engineers had become masters of the art and had codified principles of head pressure and flow that are applied in watershape design to this very day.

But Islamic watershaping is about more than science: Water was indeed precious to cultures that emerged where there was little or none to spare, and it led them to treat water with significantly greater respect and reverence than their counterparts in Greece and Rome ever did.

While the Greeks and Romans saw water as an encompassing, metaphorical expression of nature and their deities, Islamic peoples carried the concept to new and higher levels of religious intensity. They worked with water as a spiritual medium that captured and represented the four rivers of life – a design detail that can be seen in almost every example of Islamic garden architecture including the tomb gardens of the Taj Mahal.

Water was (and is) a source for them of peacefulness and spiritual connection, a link between interior and exterior spaces and, even today, a practical tool in climate control. What you see is garden spaces flowing out from courtyards and interiors, all drawn together by water channeled through small marble channels along corridors and across plazas.

The combination of art, architecture, spirituality and practicality defined water’s role in Islamic culture. We checked in on some applications of these principles last time at various locations in Moorish Spain, from the Court of the Canal at Generalife to the Court of the Lions at the Alhambra – and at the just-mentioned Taj Mahal in India (all three seen in the photo group atop the sidebar just above).

SPREADING THE WORD

Although conquest of foreign lands takes a horrible human toll on societies, the technologies that follow in the path of the conquerors can have enduring effects – as was certainly the case as a result of the Moorish occupation of Spain in the late Middle Ages.

(A similar story of technological development could be told of India’s Hindu culture and the Far East, but in this article, the direct effects of having refined, working examples of Islamic engineering on the European continent and their influence on Renaissance designers is our focus.)

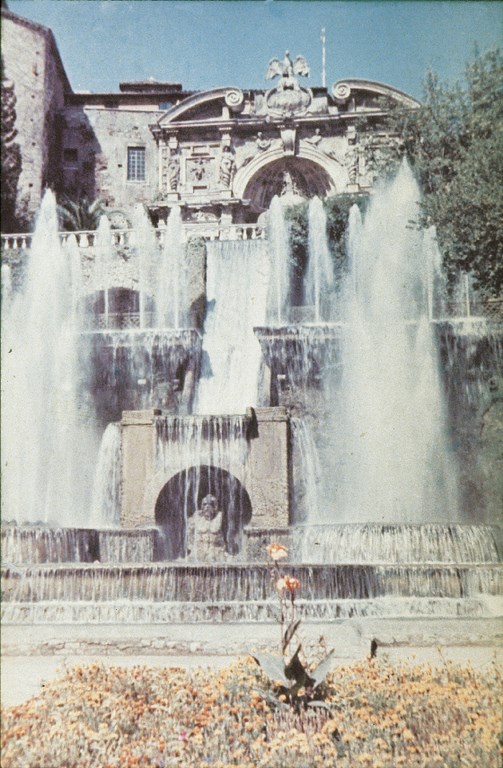

| Installed during the last half of the 16th Century on the site of an old monastery at Tivoli, the 11 major watershapes in the gardens of the Villa d’Este stand as direct testimony to just how influential Islamic principles of hydraulics were to designers of Renaissance Italy, including Villa d’Este’s Pirro Ligorio. The Way of the Little Fountains (left) isn’t used to divide its space into quadrants as would have been the case in an Islamic garden, but the small jets of water (and the engineering driving them) are a distinctly creative adaptation of the water effects found at Generalife, for example (illustrated in the cluster of photos just above). That attitude of creative adaptation and expanded use of hydraulic principles takes flight in Villa d’Este’s other watershapes – including the Queen of Fountains (middle left) and the large spout that serves as the visual terminus for a long path and grand stairway (middle right). The crowning achievement in Ligorio’s aggressive adaptation of hydraulic rules is the gardens’ Water Organ (right), a device that could, through manipulation of valves that channeled jets of water through pipes and air chambers of various dimensions, fill the area with ‘music.’ |

The watershapes Moorish designers created in Spain were unlike anything else seen before on the continent. Greek and Roman designers had refined the use of water with respect to proportions and reflection and utility, but what designers of the early Renaissance found in Spain was the possibility of using water in motion to make a much stronger and more enduring impression.

In fact, these Moorish water effects were the most beautiful displays of water and hydraulics Europe had seen to that point. Through this Spanish connection, the technologies of the hydraulic engineers of the ancient Middle East finally made their ways into the heart of Europe.

You don’t have to look any farther than the Alhambra to see where designers of the Italian Renaissance drew technological inspiration for their work at the Villa d’Este in Tivoli (just above) – or where, in turn, the designers of the Watergardens at Versailles (just below) or the Peterhoff (second photo group below) and the builders of the fountains of Rome (third image below) learned their lessons on unleashing the dynamics and drama of moving water.

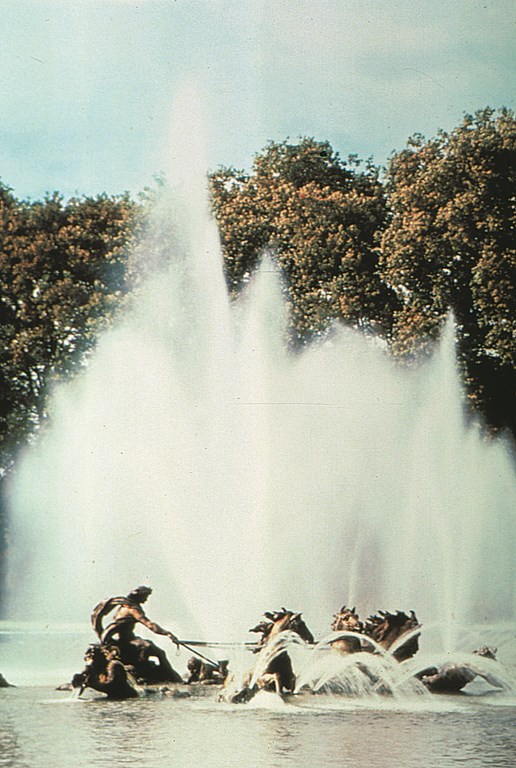

| Built for a French king with no lack of self-esteem, the watergardens at Versailles are the quintessential expression of the Baroque sensibility of the late 17th Century – an ostentatious design style that succeeded the classical themes found in Renaissance design. Elaborate and monumental in the extreme, the watershapes here were designed by Andre Le Notre to intimidate – and thereby magnify King Louis XIV’s power and glory. The Fountain of Latona, shown in views with the jets idle and actuated (top left and middle left), show the power harnessed by the Francini family through the Machines de Marly. These aren’t subtle waterspouts: These are huge volumes of water moved to impress. The same impressive/intimidating objective is served by the Fountain of Apollo (middle right): The jets here are so powerful that even the sun god is obscured by the torrent. But the water show at Versailles has many elements, not all of them volcanic. The Pool of Neptune, for instance, serves as a massive reflecting pool in which the jets offer restrained accents (right), while the Grotto of Apollo (bottom left) provides a setting for contemplation in much the same way the Queen of Fountains does at Villa d’Este (see the cluster just above). |

The Alhambra (“red castle”) was built by Mohammad ben Al-Ahmar in the 13th century and uses water in a variety of ways, but the most intriguing fact about the castle is the fact that the water is there at all. The fortress sits atop a 300-foot-high hill overlooking Cordoba, a perch that created obvious challenges in lifting water to serve its needs.

The task was simplified by the architects’ understanding of hydraulics. And the fact that these artful waterworks survived for hundreds of years after the Moors were driven from Spain enabled Renaissance engineers to dissect the systems and figure out what made them tick.

| Borrowing a trick or two from his western European counterparts, Russian Czar Peter the Great built watergardens at his summer palace in St. Petersburg with similar objectives: to impress, intimidate and achieve an overwhelming measure of self-glorification. Designed and built in the first half of the 18th Century by Jean Baptiste-Alexandre Le Blond (a student of Le Notre’s), the Peterhof can best be classified as Rococo in style. This successor to the Baroque style took ostentation to a whole new level: Gilded sculptures call attention to the fabulous wealth of the czar – and his desire to be seen on par with his western European counterparts. The achievements here are similar to those at Versailles: The water was brought nearly ten miles from the Baltic Sea to flow as a half-mile-long canal, terminating in the grand jets of 75 fountains cascading over stairways leading to the palace. None of this makes any gesture to subtlety: The watershapes strive for grandeur – and achieve it with a balance called perfect by many architectural historians. |

The 13th-century waterworks at Generalife in Granada, Spain, served as a source of immense inspiration to Italian designers as well. This summer villa, whose name translates from the Arabic as “garden of the architect,” houses the only surviving original “water stairway,” a structure of importance both for its inspiring beauty as well as the technology that makes its special effects possible.

To modern eyes, these early examples of water in motion seem familiar, even simple. But if you think of achieving their effects without the use of modern pumps, you can begin to understand the fascination and enthusiasm with which these Moorish installations were treated by designers in a Europe emerging from hundreds of years of chaos and rediscovering the technological and artistic wealth of cultures that had gone before.

TO ITALY AND BEYOND

Think for a moment about the Islamic quatrefoil, a combination of square and circle that was a central design feature of basins for fountains, courtyard boundaries and even small decorative tiles all over the Middle East, across North Africa and into Spain.

| Originally the plain, functional terminus of an ancient Roman aqueduct, the Trevi Fountain in Rome is distinguished by its scale and scope as well as for its massive incorporation of sculpture into the aquatic design. Primarily the work of Niccolo Salvi, the fountain was built between 1732 and 1762 as part of a grand architectural revival in Rome. In this era, the Papal city was dotted by massive fountains fully accessible to the public – a distinct departure from the overwhelmingly exclusive watergardening programs set up for private use by Europe’s monarchs and their courtiers. |

To the Moors, the quatrefoil was more than the geometric merging of two basic shapes. In fact, it had deep religious and spiritual significance that was lost on Europeans – but it nonetheless provided design inspiration still seen in countless watershapes throughout the modern Western world, including the fountains of the Palace of Het Loo in Holland (seen just below).

Architects of the Renaissance recognized the intensity and playfulness of ancient designers and, in Spain, had direct access to models they ultimately translated into some of the most famous watershapes on the planet.

| Built in the same time period as the chateau at Versailles, the palace of the Dutch king and queen was not so grand as the French model – but is noteworthy in this article for one compelling reason: The Venus Fountain is a modest statement of power built on a basin shaped as a quatrefoil – the dominant design element of Islamic design and an indication of just how integrated these Persian forms had become in western architectural styles. |

So while designers such as Piero Ligorio (Villa d’Este) and Giacomo Vignola (Villa Lante) in 16th-century Italy and Andre Le Notre (Versailles) in 17th-century France were conceptualizing their future achievements, hydraulic engineers pulled apart ancient waterworks and explored the systems that made feasible everything from the grand Roman aqueducts to subtle water stairways.

|

Where Do We Go from Here? Acknowledgment of our watershaping ancestors’ accomplishments is the first step in fulfilling our own dreams as builders. That’s the thought that stands behind the first two articles I’ve prepared for WaterShapes, but with the advent of CADD (Computer Aided Design & Drafting), it’s all too easy to allow ourselves to slip into a mind-set where we feel comfortable stamping out the same basic design over and over. In that context, it will take conscious decisions by each of us to do the job we really should be doing in thoughtfully creating watershapes that complete both practical and spiritual missions. We each have the resources to become great watershape designers. All it takes is curiosity about the traditions of which we all are part and an understanding of how we can work with these traditions to create modern watershapes that echo the achievements of our forebears and make the same sorts of connections with the human spirit they were able to make. In the end, it comes down to self-perception and how you see yourself in this grand scheme of things. If you perceive yourself as a “pool builder” or “landscaper,” then you will most likely be inhibited by the professions’ limits. If you can see yourself as one of the world’s finest providers of the finest watershapes, then you have no limits. Decide! – M.H. |

Particularly important on the hydraulic side of things was the Francini family, retained to bring water over two miles to the chateau at Versailles. Through trial and error, they devised a system of 14 waterwheels and 253 pumps (collectively called the Machine de Marly) that carried water from the River Seine up 300 feet to create the necessary head pressure to power the 1,400 fountain jets designed by Le Notre.

If there’s ever a watershaping Hall of Fame, the Francini’s achievements at Versailles make them a lock for charter membership: The work is magnificent in scale and scope and to this day is among the most breathtaking and inspirational of all watershapes.

As for their inspiration, you need look no farther than the waterworks at the Alhambra. To be sure, the fountains at Versailles bear witness to a different design sensibility and are grander and more dynamic and have a different purpose than the watershapes at the Alhambra, but the hydraulic principles driving them are identical.

Eventually, these hydraulic concepts migrated throughout Renaissance Europe to reach England in the North and Russia in the East. Finally, they reached the New World and have had immense influence in the Americas, north and south.

A BRIDGE TO THE PAST

In today’s world, you never need to look far to find touches of Islamic influence on watershape design.

|

Getting Involved This second installment of the “Images” series has further opened a discussion of the historical intersections of design, architecture, technology and hydraulics, but we’ll leave the overviews behind in future articles, focusing instead on specific historic watershapes, how they fit into the timeline and, often more important, how they work. If you have any requests – that is, a classic watershape on which you’d like more detailed information – please let us know by sending an e-mail to [email protected]. – M.H. |

In Washington, D.C., the whole Capitol Mall complex borrows from a vernacular first expressed hundreds of years and thousands of miles away. With its axial canals and reflecting pools, the immediate sources are French, but you see the same principles at work in India at the Mughal Gardens and the Taj Mahal.

The Spanish Revival movement so prominent in California architecture similarly traces its roots to ancient sources – most directly to the design sensibility that laid out the Alhambra and Generalife. Echoes of Islamic/Persian design now also find expression in places like tract housing in East Asia.

Along with this design sense came a sophisticated approach to hydraulics. Through the years, however, the spiritual component of Islamic watershaping fell further and further away with each new translation.

| Many examples could be used to show how modern watershaping has been influenced by Islamic design and hydraulic principles – from the Capitol Mall in Washington, D.C., to the waterways at the J. Paul Getty Museum, which we saw in the first article in this series (October 1999, p. 35). Few contemporary installations capture this design indebtedness straight back to Classical Greece, Rome and Persia as well as the watershapes at Bellagio, the grand hotel in Las Vegas (left). The hotel itself in many ways pays homage to the Villa d’Este (right down to having 11 main watershapes, a couple of them seen in the October 1999 article). As important, Bellagio demonstrates the importance of creative adaptation of design precedents – the very same tendency Renaissance designers displayed in expanding on what they found in Moorish Spain – and to similarly dazzling effect. |

This “dilution of the spirit” can be perceived both positively and negatively, depending on your perspective, but at their best, watershapes derived from Middle Eastern roots create spiritual sensations on their own as we drink in the sight, sound and feel of water in motion. This may not approach religion, as it did for the forms’ originators, but it is nonetheless a special experience that all of us appreciate even in our more secular age.

We may not be thinking in spiritual terms as we watch the waters dance at Bellagio (above) or as we stroll around the grounds at Versailles or wander the pathways at Villa d’Este, but surely there’s room in there to sense the mastery of those with a special feel for moving water’s power and promise.

Mark Holden is a landscape architect, pool contractor and teacher who owns and operates Holdenwater, a design/ build/consulting firm based in Fullerton, Calif., and is founder of Artistic Resources & Training, a school for watershape designers and builders. He may be reached via e-mail at [email protected].