Inside a Classic Style

The history of residential architecture took a real turn toward mass production with the emergence of the modern suburb early in the 20th Century. Especially in the years after World War II, middleclass families increasingly left urban congestion behind and headed for open outlying areas where developers were hard at work in preparation for their arrival.

Some developers put distinct stylistic stamps on the neighborhoods and communities they were building. Among the most popular and recognizable of these styles was the Spanish Colonial Revival – a look that has special prominence on the West Coast but that has surfaced throughout the United States and in places as far flung as Europe and China.

This style is so popular and has been used so much in so many variations that it is, these days, tough to nail down exactly what is or is not true to early Spanish Colonial motifs and ideas. That’s not surprising, because this malleable style itself represents a cobbling together of ideas borrowed from Roman, Islamic and even Native American cultures.

Those deep roots, coupled with a scattering of design focus that has blurred borders and distinctions and any sense of stylistic purity, makes it tough for 21st-century watershapers and other designers to respond to what they see when they drive to the curb and take a first look at a prospect’s home. But Spanish Colonials are fairly easy to spot, even when the original look has been altered (or mangled) – and knowing a bit about the specifics of the style and its history can be extremely useful to anyone who is asked to do design work for their exterior environments.

WARM WELCOMES

The best news from a designer’s or contractor’s perspective is that the Spanish Colonial style is enduringly popular among a substantial set of high-end clients who in many cases are discerning enough to know the differences between the real thing and collections of design errors.

If, for example, someone has revised the façade of a Spanish Colonial with a Corinthian colonnade, there are clients who will see the inconsistency and in some cases pay good money to restore the original look. Through the years, many classic properties have endured these unwelcome remodelings, and it’s generally easy to see what’s wrong and how to undo these compromises to what is a remarkably simple and flexible style.

There are many reasons for this particular style’s popularity. In California, for example, Spanish Colonial is virtually synonymous with the fabled lifestyles of Hollywood stars and other luminaries in the form of its iconic terracotta roofs, white plaster walls, open architecture, arches, courtyards, wooden doors, wrought-iron details and lush landscaping.

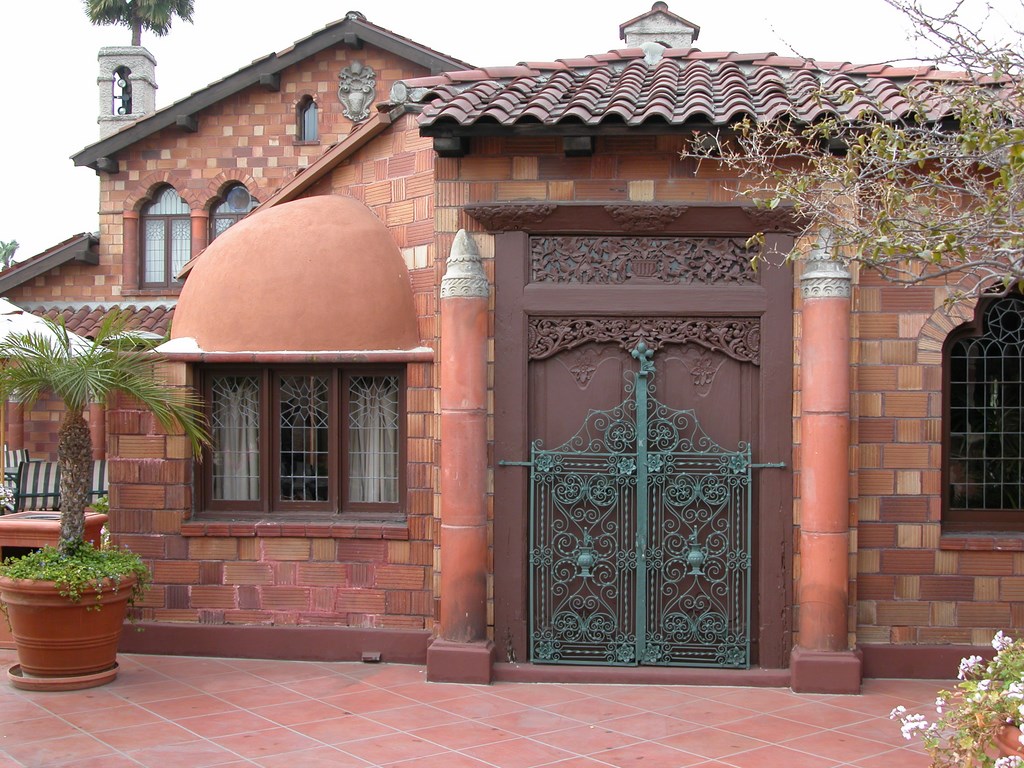

| Bell towers and other turret-like structures may be common among Spanish Colonial buildings and directly recall their mission heritage, but there’s tremendous flexibility when it comes to ornamentation, with some façades making reference to Moorish, Romanesque and Baroque precedents in architectural history while others are quite simple and unadorned. |

It’s a remarkably casual, informal style, but it was also associated early on with great wealth and opulence of the sort that made obtaining a home in this style a mark of achievement, of having “arrived.”

Moreover, because the style is typically associated with warm-weather environs, Spanish Colonial became the look of choice for resort locations that further reinforced the sense that Spanish Colonial was all about luxury and the “good life” – a symbol of quality for those migrating west to escape cold eastern climes.

These new arrivals left behind boxy homes with smaller rooms and multiple stories and craved Spanish Colonial homes with their open spaces, arches, turrets, cupolas, high ceilings and outdoor rooms – an architecture that stood in diametric contrast to the confining elements of the Victorian, Tudor or Gothic styles. The appeal of Spanish Colonial was simply spectacular and grabbed the hearts and minds of people from all walks of life.

In a romantic sense, Spanish Colonial spaces align perfectly with the concept of living or vacationing in a “villa.” This style popularized the concepts of outdoor living, courtyards and spacious backyards, and it also brought palms into the planting vernacular in warm-climate areas from coast to coast. These homes are made for comfortable hot-weather existence, with considerable allowance for air circulation as well as reflective white-plaster walls and the common use of courtyard fountains.

EL CAMINO REAL

As suggested above, the Spanish Colonial style has a wonderfully mixed bag of historic influences.

The courtyard, for example, reaches back at least to Roman times and is derived from imperial styles in the Roman territories of Iberia, where Spain and Portugal now exist. The early Iberian settlements were cramped affairs – fortified outposts, basically – and courtyards were one way colonists found to get a taste of outdoor living within the privacy of their homes.

Centuries later, the Moors occupied Iberia and introduced new stylistic elements to the urban scene. From the 9th to the 14th centuries, features of Islamic architecture from pointed arches to the use of large reflecting pools, quatrefoil fountains and other elements found their way to Spain and exercised an influence seen to this day.

| The use of water in Spanish Colonial courtyards and extramural spaces is clearly inspired by the Moorish architecture found at the Alhambra in Spain. The various fountains, runnels and reflecting pools they used to cool their living areas in Spain translated perfectly to the needs of colonists in warm New World climates. |

Well before the Spanish Colonial Revival came along, the Moorish style found in Spain was a major influence on the Italian Renaissance and gardens and watershapes that move us to this day. But once the Moors were gone, imperial Spain itself carried the banner forward, taking its characteristic architectural style with it as the seafaring Spaniards conquered and colonized much of the New World.

The climates in these areas were well suited to Spanish architectural styles, which caught on through much of South and Central America and really came into its own in the southwest of North America. The word Colonial in Spanish Colonial refers, of course, to the fact that the style spread as a result of these conquests.

The colonial style took hold in California in a big way as a result of the system of the Spanish missions that reached up the coastline at intervals marking a day’s walk. This system was linked by the King’s Highway (El Camino Real) and for nearly 200 years, these structures were California’s social, cultural, spiritual and economic hubs. Villages grew up around these adobe structures, and many of California’s leading cities have these missions at their hearts and are named after them.

| Arches of many types and descriptions are used in the Spanish Colonial style, from unornamented Roman-style arches all the way through to highly decorated Moorish forms. Again, flexibility is a defining characteristic of the architecture, particularly when it comes to large-scale public or commercial properties. |

Now mostly tourist attractions, some of the missions (Santa Gabriel, for example) are quite well preserved and stand as the most original and authentic models for the Spanish Colonial Revivalists. Similar compounds and public buildings existed throughout Mexico and Central and South America, and their prominence is one reason why the Spanish Colonial style is alternately known as the Mission style.

By the early 20th Century, California had long been part of the United States and the emerging middle class was taking its place in the sun, setting the stage for a Spanish Colonial Revival that would make the style an ever-increasing feature of the suburban scene beginning from about 1910 on.

CALIFORNIA GOLD

The decades that followed saw a dizzying expansion of suburban communities as well as incredible economic, social and population growth of the American West. Along with that growth came a flowering of the Spanish Colonial style at the hands of a small group of extraordinarily prolific and influential (yet relatively unknown) architects who understood the appeal of the style and put it to use in designing public buildings (including lots of city halls) as well as homes of the affluent.

These designers – among them Myron Hunt, Wallace Neff and George Washington Smith – built scores of estate homes that expanded and celebrated Spanish Colonial motifs and concepts in ways that codified the style. At the same time (but to a lesser extent), architectural giants including Greene & Greene, Frank Lloyd Wright and Julia Morgan also worked with Spanish Colonial elements in certain projects – and increased the style’s appeal among wealthy clients.

Before long, the basic simplicity of the style had grown to include a spectrum of balconies, peristyle treatments, porticos, elaborate courtyards and verandas – all used to add to the size, visual interest and complexity of the core design concepts.

| The use of elaborate wooden gates and wrought iron grates and barriers is common among Spanish Colonial structures of all sorts, residential and commercial alike. These details seem right at home amid the stonework and tile and represent another way to bring ornamentation to otherwise simple architectural forms. |

At the same time, this early period saw the development of a distinct planting palette that has been associated with the style ever since – choices based largely upon plants that were tolerant of the climate and readily available. This included various species of palms along with bougainvillea, birds of paradise and ficus, pepper and olive trees, all of which became synonymous with the style even though those plants had almost nothing to do with Old World roots or practices in the actual colonial period.

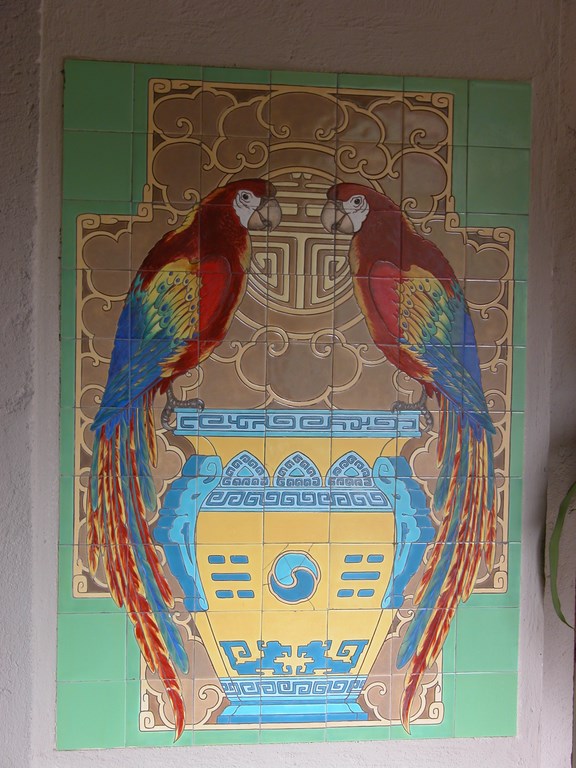

It was also during this time that brightly colored, hand-painted ceramic tile became a key fixture in Spanish Colonial design as accents for architecture, watershapes and hardscape treatments. Firms including the Catalina Tile Co. virtually invented this particular tile form, and the geometric and organic imagery developed in the early part of the last century is still the pattern for much of the decorative tile being manufactured today. Color had little to do with the style at its origins, but it did seem to flow naturally from the colorful tapestries, textiles and pottery of Mexican and Native American cultures.

It was during the formative years for the style that the aforementioned association with luxury and glamour emerged in full force. To this day, elite California communities including Bel Air, Beverly Hills, the Hollywood Hills, Pasadena and Montecito are filled with beautiful structures built in the golden era of early-20th-century residential architecture. Some communities, Santa Barbara chief among them, are so determined to maintain this stylistic heritage that building and architectural codes favor the Spanish Colonial style above all others.

AGUA DULCE

Given the rise of Spanish Colonial style in warm climates, it’s no surprise that it has become closely associated with water. Indeed, the style is all about beating the heat – hence the white plaster, terracotta roofs and open interior spaces.

At root, of course, the use of water in Roman and Moorish Spain as well as in the Spanish colonies was strictly utilitarian. The California missions, for example, featured systems of basins and cisterns that were employed purely for the purpose of providing water to those who gathered on the grounds. This water was used for drinking and food preparation as well as for bathing and washing clothes. At first, the containers had little or no ornamentation.

Later, the same water was put to decorative purposes in the form of courtyard fountains – but even here, there were practical, utilitarian implications in that the moving water had the effect of cooling the spaces in which it evaporated. In designing these more overtly decorative fixtures, it was natural for the mission artisans to refer to Spanish/Moorish precedent and to work with quatrefoil basins surmounted by overflowing bowls – often with sculptural centerpieces.

| Central courtyards are a major design element of the Spanish Colonial style. These are places where plants, arbors, covered arcades, balconies and vivid colors all come into the picture – and again, there are few rules when it comes to the materials or configurations or combinations in which they appear. |

In modern applications, the decorative nature of these fountains is accented by the use of the brightly colored ceramic tiles mentioned above. This use of tile isn’t “authentic,” but it’s been part of the style’s design vocabulary for the past 100 years or so.

The presence of swimming pools within Spanish Colonial programs is, of course, another modern addition to the style. Even here, however, we see the adoption of design cues that reach back to Moorish Iberia and the large, rectilinear reflecting pools and runnels found at the Alhambra and Generalife in southern Spain. Those looks, combined with the more modern association with luxury, has conspired to make the rectangular swimming pool a seemingly natural, honorable and seemingly ancient adjunct to Spanish Colonial homes.

Although these modern accretions are subject to much variation because of a general lack of authenticity, they nonetheless tend to enjoy the greatest visual success when they follow basic principles of shape and style readily associated with Spanish Colonial’s architectural roots. A naturalistic rock pool, for example, would be out of line, as would pools with Grecian-style radiuses. Even so, on this level it’s about following a distinct spirit rather than firm design precedent.

This limited watershaping palette may constrain the designer to some degree, but the enforced restraint ultimately works out for the best with the style’s decidedly simple elements.

ALL MIXED UP

The key to working with the Spanish Colonial style is an awareness of the basic elements of the style as well as a sensible, sensitive approach to extensions of the style to suit modern needs.

This awareness has become particularly important in recent years because so many practitioners (architects, landscape architects, watershapers and others) have done an amazing a job of mixing so many alien references into their “Spanish Colonial” projects that they’ve become almost unrecognizable as such.

| Although they are generally 20th-century additions to a much older design tradition, the tile and other craftworks that have become synonymous with Spanish Colonial style fit in perfectly with their surroundings – so much so that it would be hard to get things to seem right without them. |

One of the big points of confusion has to do with the also-popular Mediterranean style, which is itself a blend of Roman, Italianate and Renaissance motifs. These days, for example, we see all sorts of buildings that are labeled as “Tuscan,” but most bear no resemblance whatsoever to buildings actually found in Italy’s Tuscany region. When these Mediterranean motifs, watershape types, plant selections and design details collide with Spanish Colonial features, any sense of design provenance goes right out the window.

We’re also seeing more and more housing developments that are being built with no governing style at all beyond superficial, non-integrated use of classic Spanish Colonial elements such as terracotta-tile roofs, white plaster and/or the use of arches on door or window treatments. This is an unfortunate bastardization of what should be one of the simplest, purest styles available to today’s designers.

| Water has been part of Iberian architecture since Roman times, often in the form of the cooling reflecting pools that occupy prominent positions in courtyards. They typically have rectilinear forms in today’s Spanish Colonial courtyards in response to that historical precedent and are usually finished with colorful, expressive tile. |

As is true of many things related to art, architecture and design, whether something “works” or not tends to be a subjective judgment. To discerning eyes, however, the trend toward smashing genres together – even entities that would seem as simpatico as Spanish Colonial and Mediterranean – absolutely dilutes all styles and turns design into a commodity of little value.

Not all of the contemporary variations on Spanish Colonial style have been deplorable, of course. Landscape artists such as the great Roberto Burly Marx translated the vocabulary of the traditional style into exteriors that are bold and wonderful, while Mexican architects Luis Barragan and Ricardo Legorretta have created an all-new genre that transforms the basic Spanish Colonial spirit into dramatic tapestries of color, flat planes, light and texture.

LEVELED OUT

The long and short of it is that Spanish Colonial style is something that has become codified to a point where it can be used on different levels and will always be best served by designers and builders who are consistent and play things by the book.

In some cases, touches that merely hint at the style are enough to create a sense of distinction in a landscape or watershape. At the other extreme are projects in which authentic reproduction or restoration of Spanish Colonial details is the goal. (I’ve been involved in several projects of the latter sort in which I’ve been asked to restore Spanish Colonial homes to complete and literal 1920s authenticity.)

| Fountains and statuary of all shapes and sorts are appropriate – and most feature beautiful tilework, although I have a hard time arguing against the naturalistic-grotto look, which also seems to fit nicely. Whatever the form, it’s all about cooling the air with moving water – a strategy for beating the heat that architects have been using for centuries. |

The point of this awareness-raising exercise is quite direct: We as designers and builders and inheritors of the design tradition have a responsibility to recognize the characteristics of design styles and recognize their transcendent value not only to a home’s current occupants, but also those who will live in it for generations to come.

It is our obligation to preserve these great homes and surroundings, restore them to near-original condition when we can and resist the recent tendency to treat architectural and design styles as a grab bag from which anything can be taken and used at will, no matter how slim or inappropriate the connections between various selections.

As watershapers in particular, we need to recognize that our work is invariably a late addition to the Spanish Colonial menu and that we have an obligation to respond appropriately to the setting. The materials we have to work with – simple combinations of terracotta, white plaster, wood, iron and ceramic tile in our courtyards, fountains and pools – is in that sense a treasury to which we can return time and time again to tremendous effect.

Ultimately, it is our sense of the internal logic and historical background of the Spanish Colonial style that enables us to make sure these spaces really do satisfy tradition – and let their lucky owners enjoy a healthy slice of the good life.

Mark Holden is a landscape architect, pool contractor and teacher who owns and operates Holdenwater, a design/build/consulting firm based in Fullerton, Calif., and is founder of Artistic Resources & Training, a school for watershape designers and builders. He may be reached via e-mail at [email protected].