Building by Water

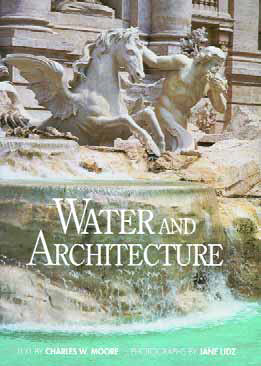

When I first picked up Water and Architecture by Charles W. Moore (published by Harry H. Abrams in 1994), I thought I’d found the perfect resource for those of us who design and build contained, controlled bodies of water. As I delved into this book’s incredibly well-illustrated 224 pages, however, for a short time I worried that the text was mostly irrelevant to the working lives of watershapers.

Ultimately, however, I found the text to be very helpful – even if it wasn’t in the manner I had initially thought.

I was disheartened initially because the text seemed so broad in its coverage of water and architecture – and so rooted in history and philosophy – as to be of little practical use. Specifically, Moore deals with subjects as grand as rivers, oceans, harbors and architectural history in very broad and almost sociological terms, and it seemed that I would find little I could apply in my own work.

I soon came to understood, however, that what this text was really about was how water and architecture go hand in hand to create some of the most remarkable environments ever crafted by mankind. And from that broader perspective, my mind was opened to wonderful explorations of spectacular human achievements – discussions that make this book a must for any watershaper concerned with expanding his or her knowledge and perspective of what’s at stake in our daily activities.

And there is a section of the book that deals specifically with still- water systems, including swimming pools, reflecting pools and ponds. For the most part, this is an examination of the power of reflection and of the value of the stillness that water can provide. Most prominently, Moore considers the Taj Mahal and asks whether we’d pay as much attention to it had it been built without its reflecting pools. How diminished that space would be!

But he also deals with water on the grandest of scales as well. In a section describing architecture by the sea, for example, Moore cites Hong Kong’s harbor as a prime example of an entire city that gains its character from the water, discussing the way the water offers a tranquility that counterbalances the bustle of the city that rises from its shores.

Throughout the book, Moore offers similar observations and insights into an array of remarkably famous settings and their attendant watershapes, including the canals of Venice, the fountains at Villa d’Este, the waterworks at the Alhambra and a few more modern examples, such as San Antonio’s famous Riverwalk and, most profoundly, Frank Lloyd Wright’s Fallingwater, which Moore cites as a fantastic confirmation of the power and importance of the use of water in human environments.

He also discusses monumental uses of water and, for example, the Jefferson Memorial, which gains much of its drama and character by way of its proximity to water. He also considers the way water is used in urban environments to combat claustrophobia, and how it is used in intimate spaces to bring a sense of the natural world into mankind’s decidedly un-natural settings.

One of the most fascinating parts of the book concerns the famous Italian engineer Bernard Forest de Belidar, who from 1737 to 1753 published four volumes devoted to what probably could’ve been termed “watershaping” had the phrase been around back then. Moore examines Belidar’s ground-breaking descriptions of basic water effects such as sheeting waterfalls, water cannons, basins, cascades, water organs, grottos and more, pointing out that this is very much the same set of principles and effects we use today.

His point is clearly that designers and architects working with water today are not creating anything particularly new under the sun, but instead are working as interpreters of a great tradition within a broader architectural field. Indeed, Moore’s achievement here is to remind us forcefully that today’s watershapers are in fact expanding on centuries of design and art history. The discussions in his book may not be as practical as those in some of the other texts covered in this column, but they are inspiring and vastly informative nonetheless.

Mike Farley is a landscape designer with more than 20 years of experience and is currently a designer/project manager for Claffey Pools in Southlake, Texas. A graduate of Genesis 3’s Level I Design School, he holds a degree in landscape architecture from Texas Tech University and has worked as a watershaper in both California and Texas.