Ben Franklin, Electrician

Why does the current flow?

That was the question we left on the table at the end of our last session. We had pretty well nailed down the ampere as being the basic unit of measurement of electric current, in that it describes the quantity of flow of electrons from one place to another. We were about to examine the volt, the ohm and the watt when the current-flow question arose to command our attention.

To get a firm handle on this, we are forced to backtrack a bit. Actually, we have to go back a long, long way – about 60 million years, to when a particular species of pine-like trees grew along the Baltic coast. Over the millennia, the resin from those trees became fossilized, producing the beautiful, beer-colored material called anbar by the Arabs. The Spanish corrupted that into the name that we use for it today: amber.

Many of us will recall an elementary-school field trip to the museum where we stared in fascination at an ancient bug trapped forever in a lump of amber. There is evidence that man has used amber for more than 10,000 years – as a medicine, as jewelry, even as amulets to protect against witchcraft.

But it’s the Greek connection with amber that is of the greatest interest to us in our discussion of things electric.

TALES IN AMBER

The Greeks recorded the fact that when a lump of amber was rubbed vigorously with a piece of fur or soft cloth, it acquired the magical ability to attract small particles of dust, thread and other matter. Although they could not begin to explain this phenomenon, it became a popular topic of discussion – the parlor trick of its day.

The Greeks had their own word for amber – it was “hlektron.” That’s approximately ilektron in English – our word electron. This phenomenon eventually became known as the “electron effect”; today, we refer to it as static electricity. (A whimsical thought: If English had been popular for scientific dialogue a few hundred years ago, we might be using the words ambericity and amberonics instead of electricity and electronics.)

By the early 1700s, the people studying such things were convinced that there were two distinctly different forms of this electric “fluid”: that produced by rubbing amber, hard rubber, sealing wax or other resin-like substances, and that produced by rubbing vitreous (glass-like) substances such as glass or mica. These names stuck for a while, with the scientists of the time referring to resinous electricity and vitreous electricity.

How did they know they had two distinctly different forms of a phenomenon?

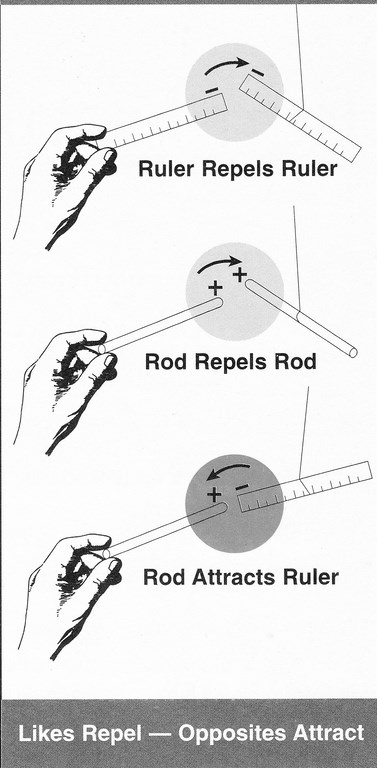

They observed that a rubbed piece of amber will attract the same bits of dust and thread that are attracted by a rubbed glass rod. They didn’t learn anything from that, but when they brought a piece of rubbed amber near another piece of rubbed amber, they found that they repelled each other. And when they brought a piece of rubbed glass near another piece of rubbed glass, they saw that they repelled each other, too.

But when they brought a piece of rubbed amber near a piece of rubbed glass, they found that they attracted one another! Therefore, they reasoned, the electric charge on the amber must be different from the charge on the glass.

ALL CHARGED UP

Through the years, it has been shown that every object that can hold a charge of static electricity will fall into one of these two categories: It will either be attracted by the amber and repelled by the glass, or it will be attracted by the glass and repelled by the amber.

Try it yourself: The accompanying sketches show how to set up a little experiment using a pair of plastic rulers (for the resinous elements) and a pair of glass rods (for the vitreous elements). The rulers should be easy to come by – or any thin strip of plastic will do. And you can substitute a pair of wine glasses for the glass rods – empty and dry, please.

Charge them all up by rubbing vigorously with a soft cloth or by stroking them through a friendly person’s clean, dry hair. Or, best of all, give each item a few strokes with the family cat, providing, of course, that the family cat is willing and has previously shown an interest in fundamental science.

These things were all known by the 1740s, but not truly understood or well documented. That began to change when Benjamin Franklin took an interest and sponsored a series of electrical experiments. It wasn’t long before he leaped in with both feet and purchased the experimenter’s devices and apparatuses so that he could delve deeper into the subject. The results of Franklin’s involvement are still with us today.

Two quick thoughts regarding Franklin are in order here: First, although he benefited from less than two years of formal schooling, he retired from the business world at the age of 42 with a modest fortune acquired primarily from his printing and publishing interests. It was after his “retirement” that he became active in government, became postmaster general, promoted the first hospital in the colonies, founded the University of Pennsylvania and the American Philosophical Society, developed the concept of Daylight Savings Time, investigated the Gulf Stream, was a principal author of the Declaration of Independence and, at the age of 75, sailed to Europe to negotiate the final peace with Great Britain. That’s some retirement!

Second, our minds’ eyes have us locked on Franklin as he appears on the $100 bill – a good likeness of him when he was in his seventies. But when we think “electricity,” we must see a much younger man, because the kite-flying-in-the-thunderstorm incident took place when Franklin was just 46. By ten or 15 years later, he would have gained enough knowledge about electricity that he would never have tried such a dangerous experiment. All in all, quite a guy.

FINDING THE FLOW

Franklin’s experiments led him to the conclusion that there was only one kind of electric “fluid” and that the difference from one charged substance to another corresponded to whether the substance had either an excess or a deficiency of that fluid. He said that the rubbed glass rod had an excess of vitreous electricty and was, therefore, a positively charged body; conversely, the rubbed amber had a deficiency of vitreous electricity and was, therefore, a negatively charged body.

Thus, Franklin proposed that when a positively charged body comes in contact with a negatively charged body, the electric current must be flowing from the first body (where there is an excess) toward the second body (where there is a deficiency). In other words, everything must equal out – that is, neutralize.

In the 100 years following Franklin, other scientists proposed two-fluid theories that have proved to be closer to reality than Franklin’s single-fluid idea – although the factors involved are much more complex than visualized by any of them.

Franklin acknowledged that his choice of which term went with what substance was arbitrary, and to some degree we might wish he had reversed his use of positive and negative. In any event, we continue to use Franklin’s terminology today. Our present understanding of the structure of atoms, for instance, provides us with positively charged protons and negatively charged electrons.

We also know that nature does not allow any imbalance to exist for long: Likes attract and opposites repel. When those opposites are negatively charged electrons and positively charged protons with a conductive connecting path, we can expect a current flow – a movement of negatively charged electrons through a conductive path.

Incidentally, Ben Franklin also coined the terms plus and minus, charge and discharge, conductor, electric shock, stroke and electrician – a term he used to describe a scientist dabbling in electrical experimentation. His inventions include the rocking chair, bifocals, the Franklin stove, the odometer and his most important, the lightning rod, which is in worldwide use today, virtually unchanged from the original model. And I can’t find time to go get a haircut . . .

Jim McNicol was a technical consultant to the swimming pool, jetted bath and spa industries. He worked on development of equipment standards for pools and spas throughout his career and was honored for his service by the National Spa & Pool Institute.