Back to the Garden

The gardening impulse of the Japanese is truly ancient. In times before recorded history, sacred outdoor spaces around Shinto shrines and Buddhist temples were arranged according to this design vision. And through more than 1,000 years of recorded history, gardens have been created and refined by priests, warriors and emperors alike in spaces both public and private.

The style isn’t original in the strictest sense: In many ways, the gardens of Japan find their sources in Chinese gardening styles and landscape painting. But the Japanese developed and refined their borrowings to fit their own national taste for subtle naturalism and elegant rusticity. The result is an amazingly coherent and distinctive landscaping style that now can be experienced at hundreds of public gardens in Japan.

The nice thing today is that you don’t have to live in Tokyo to appreciate Japanese gardens – or to incorprate their principles into your designs.

In fact, garden designers around the world now use the obvious elements of Japanese gardens – the stone lanterns, gravel and clipped azaleas – in naturalistic and asymmetrical settings of all shapes and sizes. In some cases, the total look of the garden is Japanese; in others, its principles are used to complement or enhance a garden space of any other style, from formal or contemporary to English country or Mediterranean.

There’s a flexibility to the style that makes it work across all these lines. Let’s take a look at the basics to discover why this is so.

FRAME THAT VIEW

One of the cornerstones of Japanese garden design is an integration and connection of interior and exterior views. Japanese homes open out to gardens, and garden vistas are carefully crafted for access from every room.

This access is made easy by the fact that Japanese houses are of post-and-beam construction, which means the spaces between the posts can be filled with wooden panels that slide open to reveal floor-to-ceiling garden views. In effect, the garden decorates one wall of the room, just as the interior walls are decorated with painted paper screens.

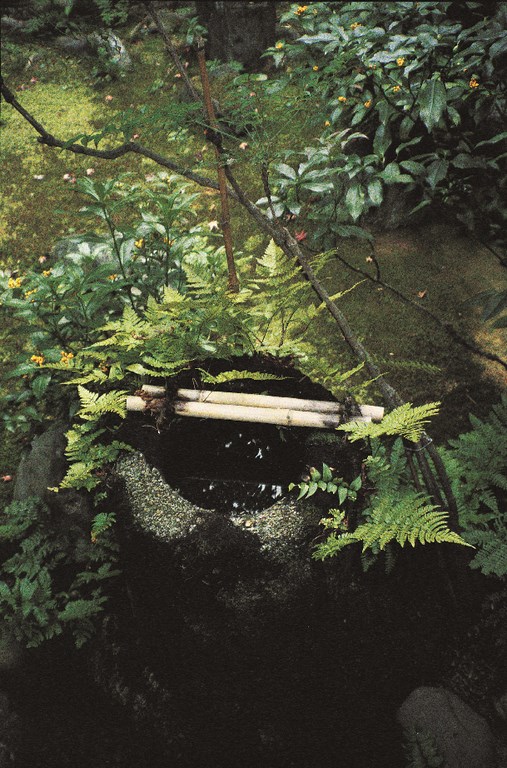

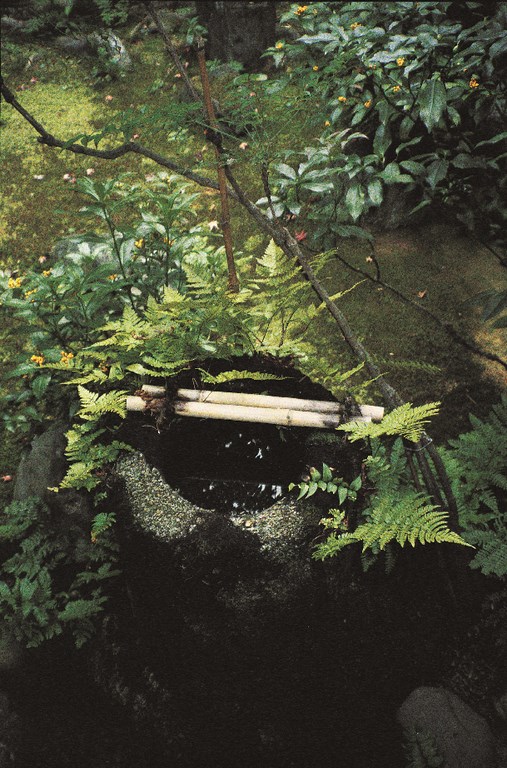

| SMALL IS BEAUTIFUL: No matter how small a Japanese garden might be, there’s always room for a small basin to bring the sound of moving water to the setting. These basins come in all shapes and sizes – another case where the flexibility of the style lets the designer exercise his or her creativity and spirit. |

Some of those views are close-ups: At Sesshu-in, a famous 15th-century garden in Kyoto, a small garden crowds up to the edge of a veranda. Enclosed by a hedge on one side and a bamboo “sleeve fence” extending three feet out from corner of the building, this small area is only eight or nine feet square – and is densely detailed with stones, moss, ferns, podocarpus and a beautifully tiered camellia as well as a carved stone lantern and a tall water basin.

Other garden views are designed as panoramas, including large spaces running along the long side of a meditation hall or living space in a private residence. These larger gardens are often constructed in three or four planes.

As in Chinese painting, the layering of these horizontal planes gives a sense of depth and complexity. Closest to the building is the foreground plane, often an expanse of raked gravel or the edge of a narrow wooden veranda that surrounds the building. Next, the middle ground may contain important stonework, a small pond or a symbolic tree of some kind.

Moving farther from the observation point, the background layer may contain a waterfall or other source for the pond or, in a dry garden, consist of a grove of bamboo, a cryptomeria forest or a wooded hillside merging into the natural scenery. Added to these is a fourth optional layer, the shakkei or “borrowed scenery” of distant mountainsides or even a neighboring pagoda.

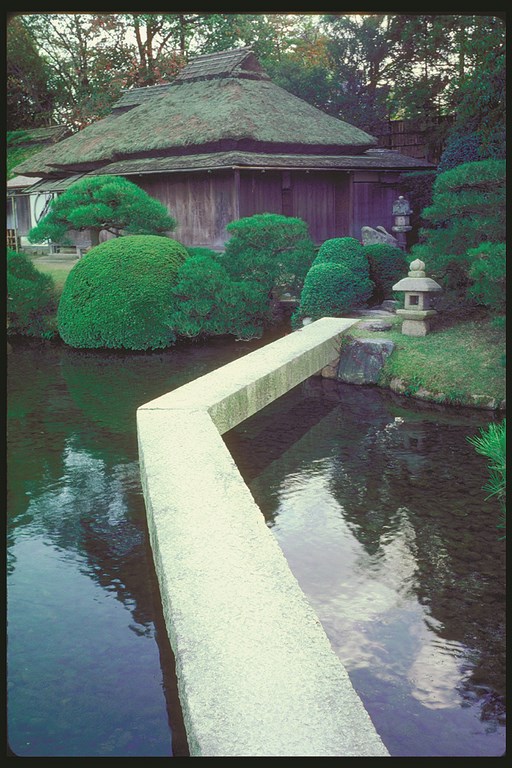

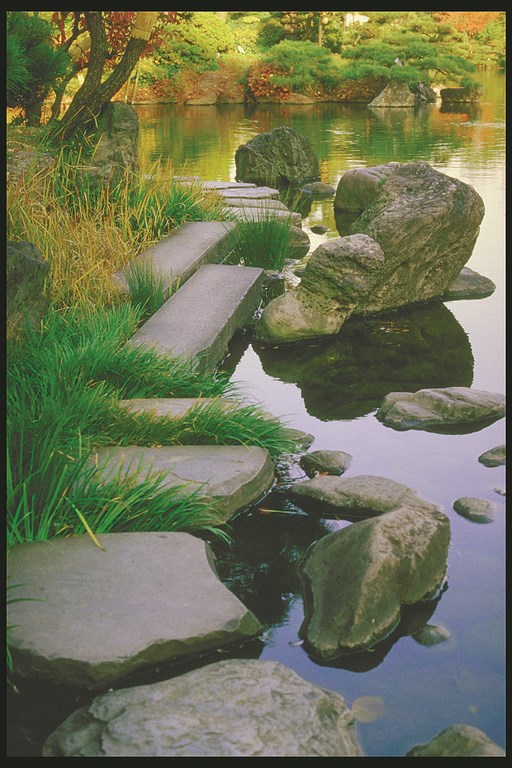

| FLEXIBILITY AND GRACE: Bridges are a prominent feature in many Japanese gardens and come in many shapes and sizes, from sweeping wooden structures to simple stone arches. Here are three unusual ones: You might not be able to borrow these designs directly, but the daring forms can inspire and be adapted for edge treatments, footpaths and decorative touches. |

In addition to views from indoors out, visual compositions are framed in the openings through roofed garden gates and through windows in walls and buildings. Windows are few and they have distinctive shapes – round, rectangular or flame shaped as in Buddhist temples – and come with sliding shoji screens to reveal or conceal what lies beyond.

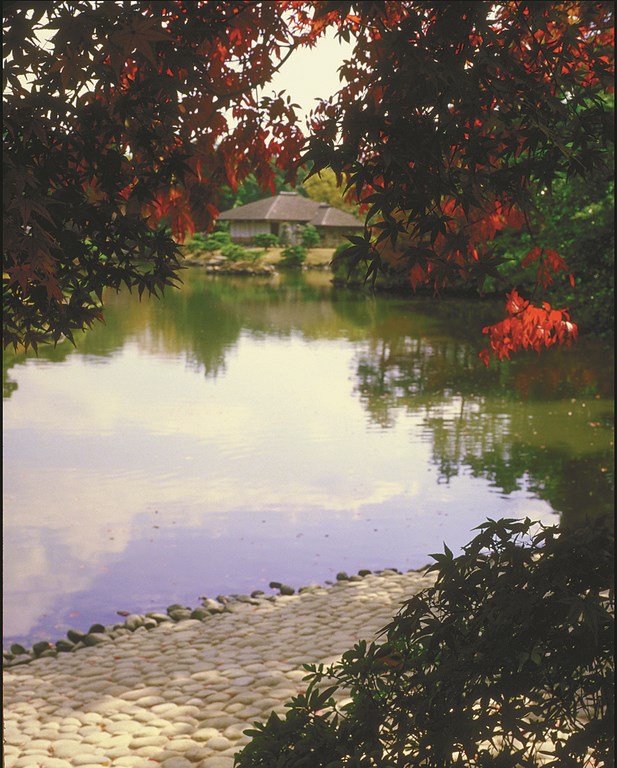

The famous round window at Genko-an, a Zen temple in the Kyoto hills, shows a small close-up arrangement of trees and stone that is part of a larger garden that can be seen in its entirety from a nearby tea room. At the famous Silver Pavilion, a flame-shaped window frames a hillside of maples, brilliant in their fall colors.

CHOREOGRAPHED SCENES

Like Japanese gardens, many outdoor spaces in the United States (and particularly those in warmer climates) are “used” most of the time by being viewed from indoors. Any such installation can benefit from the same sort of careful attention to sight lines, shapes and sizes of windows – and by designing the area so that major elements (pergolas, specimen trees, sculptures and watershapes) are placed directly in view of the windows or along pathways.

In this sense, the Japanese garden designer choreographs the visitor’s experience by, alternately, revealing and concealing views. The most common device for this is the placement of a wall that encloses the garden space, setting it off as a place apart. In large gardens, these walls are often massive, rammed-earth constructions with a plaster finish and glazed tile top; in residential gardens, all it might take is a rustic fence made of boards, or perhaps a dense, clipped hedge is used. These are usually four to five feet high – just high enough to conceal the garden, but low enough to reveal hints of treetops or roofs.

As the visitor enters the garden, typically through a formal gate, the gardener chooses what will be seen first. The branches of a maple tree may sweep down to obscure an uphill view that opens out with a few paces. Or tall hedges may turn a path into a tight, dark canyon, creating a sort of “scenery deprivation” that will heighten the thrill of the broader view the visitor encounters at the end of the trail.

As a corollary to this rule of conceal and reveal, footpaths in Japanese gardens never go directly to their destinations. The familiar American-style walkway, perpendicular to the sidewalk and marching straight up to the door, is not a part of the Japanese tradition. In the typical entry to a garden of a residence or a minor temple — a small, shallow space, no more than 15 or 20 feet deep – the visitor steps through a roofed gateway onto paving that slants to the left or right.

This pathway might even split in two, as a Y shape. Here, the triangle between the arms of the divided path will be filled with something eye-catching – perhaps an old pine tree, some interesting rockwork, a waterfeature or low-growing bamboo.

| BREAKING DOWN BARRIERS: The designers of these spaces had a special sensitivity to edges as transitions from water to land. Again, Japanese-garden style isn’t about right ways to do things; rather, it’s about finding a solution that works in the setting and reinforces an overall sense of tranquility and beauty. |

Even if the pathway starts out straight, it may make a series of 90-degree turns before it reaches the true entrance. In this sort of “stroll garden,” gently curved paths dodge out of sight behind mounded soil or billowing shrubs, or veer off at an angle through a gate. Stepping stones zigzag toward unseen places between hedges.

This device of the indirect path and the hidden goal has several aesthetic and emotional effects: It heightens the viewer’s sense of mystery and adventure in the garden while focusing attention on details of stones, plants, light, shadow, and water. This makes the garden seem larger because so much more of it is fully experienced and appreciated.

SMALL WATERS

Japanese gardens are prized for their splendid use of water – always presented in its most natural guise, whether large or small.

On the large scale, imperial villas overlook enormous lakes that once were used for boating parties, while many temple gardens feature sizable ponds with symbolic “islands of the blessed.” But even these large gardens feature special ponds and streams that are small enough in scale for use in home gardens.

Some of these small ponds suggest natural springs. At Ryoan-ji, site of a famous 15th-century rock garden, there is a beautiful small pond tucked up against a steep hillside, presented as if fed by a runoff or by a natural spring. Overhung with vegetation, this watershape offers a simple and pleasing counterpoint to the stones and gravel found on the opposite side of the abbot’s quarters.

Make no mistake: Brooks and streams used in Japanese gardens are often amazingly compact. For instance, the 17th-century garden at Shisen-do, a Kyoto hermitage for a samurai who retired to a life of art and Zen meditation, features a tiny rivulet that runs along the edge of the veranda that is just 6 to 12 inches across and only 9 to 10 inches deep. This ribbon of dark, shining water meanders between rocky banks planted with grassy sedges and mosses, refreshing and charming those who sit next to it. Similarly, the broad sheet of water and wide flat streams at Murin-an, a garden built in 1896 for a government official, are bright and reflective – but surprisingly shallow, a mere 1-1/2 inches deep in some spots.

Make no mistake: Brooks and streams used in Japanese gardens are often amazingly compact. For instance, the 17th-century garden at Shisen-do, a Kyoto hermitage for a samurai who retired to a life of art and Zen meditation, features a tiny rivulet that runs along the edge of the veranda that is just 6 to 12 inches across and only 9 to 10 inches deep. This ribbon of dark, shining water meanders between rocky banks planted with grassy sedges and mosses, refreshing and charming those who sit next to it. Similarly, the broad sheet of water and wide flat streams at Murin-an, a garden built in 1896 for a government official, are bright and reflective – but surprisingly shallow, a mere 1-1/2 inches deep in some spots.

The smallest waterfeature in a Japanese garden is the chozubachi, the ceremonial water basin, which is often fed by a bamboo spout. These basins come in several forms, from low, horizontal rocks to taller granite columns or upright natural stone fitted out with man-made hollows for water. Whatever form they take, these small vessels hold a mere 10- to 12-inch circle of water that does everything a larger lake or pond does: They reflect the sky, the moon and tree branches and form the perfect spot for placing a single white camellia or floating a ruddy maple leaf.

Along with the sparkling reflectivity of the water, the Japanese gardener focuses on and takes advantage of its sound. We hear streams that whisper, gush, chuckle or chortle, all of which depend on how stones are arranged in the riverbeds. Often, running water is heard before it is seen, thus separating the two sensory impressions and heightening each – an effect that’s easily accomplished in any kind of garden space.

GREEN ON GREEN

American and English gardens, particularly those of the 20th century, are generally concerned with creating color effects by using rich palettes of flower hues as well as colored and variegated foliage – not to mention all the possibilities of the hardscape surface colors and watershapes.

By contrast, the Japanese garden is a symphony of green. The ground is often a lumpy carpet of moss, shading from yellow-green to grass-green and tinged rusty in places or splashed with gray lichens. Out of the moss and lichens rise the vertical stems of bamboo or the columns of small pines. These are the “bones” of the garden, present through summer’s heat and humidity and the cold, wet snows of winter.

| INDIRECT ACCESS: Japanese gardens tend to prize indirect approaches, a sense of options and a joy in discovery. As you approach this “fork in the road,” you can move in one direction where you might see the water basin; take the other path and you might only hear a trickle of water flowing into it. The stepping stones add to the meditative quality: You have to pay attention, size up each stone and consider where each step takes you. |

It’s not that flowers are shunned in the Japanese garden. We find cherry blossoms in spring, irises in July, hydrangeas in September and brilliant maples and ginkgoes in fall. But these come and go amid an enduring greenery, creating an effect of transition in the midst of great tranquillity.

Beyond these visual specifics, the great tradition of the Japanese garden is the underlying philosophy: These spaces are sanctuaries of quiet and repose. They are places to sit and stroll and enjoy the fullness of the present moment while sensing a connection to the past and future.

The beauty of this approach is that it can be applied using a broad range of plants and materials and in sizes ranging from postage stamps to woodland parks. Plantings most traditionally associated with Japanese gardens need not be present to create a sense of discovery and tranquillity. Because of this tremendous flexibility, the designer can incorporate indigenous rocks, plants and scenery while creating a space that is at once inspired by Japanese design, but vested with the beauty of the surroundings.

It may not be Kyoto, but it’s still a great place.

Elizabeth Navas Finley is a master gardener and landscape designer based in Northern California. She writes a regular column for the San Francisco Chronicle about gardening around the world. A student of the landscaping and gardening traditions of diverse cultures, she recently completed a four-year sabbatical in Japan studying design principles of Japanese gardens.