Artful Education

More than three years ago, I was approached by a talented landscape architect (and good friend) to look at project with an interesting twist: the celebration of the agricultural history of a well-known California city.

I’ve long been fascinated by history and have taught the history of art and architecture in a variety of settings, so when Lance Walker (then principal at The Collaborative West, San Clemente, Calif.) called me, I was keenly motivated to hear more about his plan to pay homage to those who had jump-started a major modern community by harnessing a natural watercourse to meet its needs for potable and agricultural water.

That city, Anaheim, is better known today as the home to Disneyland and professional baseball and hockey teams. But long before all that, the city was established as an agricultural center focused originally on viticulture – that is, growing grapes for wine. Just as the Romans had often done 2,000 years earlier, citizens of Anaheim followed a pattern in which a remote water source was diverted and redistributed for purposes of irrigation.

| Although allowance was made for the minor adjustments that we knew would be needed once everything was up and running, the gravity-driven runnels were put in place with a great deal of care and precision as we worked amid the concrete contractors preparing to apply their multi-colored flatwork. |

My firm, Holdenwater of Fullerton, Calif., was brought in to consult on this unique project, which turned out to be a prime example of how modern watershaping and landscape art can be used to express the abstract, the historical and the educational.

FOLLOWING THE PLAN

The concept revolved around saluting the original water system conceived by the mostly German and Austrian settlers who came onto the local scene in the middle of the 19th Century.

| The headwaters of the system is a rock meant to symbolize the San Gorgonio Mountains, whose snow-capped peaks are seen in the distance above the serpentine flow of the stream that meanders from the boulder over to the runnel system. |

Everything about the project was based on records preserved in Anaheim’s archives. Before I joined the design team, Walker had already brought in a pair of environmental artists – Tom Drugan and Laura Haddad of Haddad/Drugan in Seattle – who dug up the documents and saw a way to diagrammatically represent this history.

All of this effort had to do with a new park to be located within a housing development known as Colony Park. It wasn’t a large space (at about 200 by 400 feet), but to me it had the big advantage of being a watershape just off Water Street.

|

History’s Course Grapes never did particularly well for the German and Austrian farmers who settled Anaheim, Calif., and established its irrigation system, but before long citrus trees took hold and did so well that eventually the whole county of Orange was named after the region’s leading cash crop. Today, the vineyards are long gone and most of the orange groves have given way to urban development, and that’s one of the reasons why the developers of Colony Park decided to fill its open space with a teaching watershape that will bring contemporary residents up to speed with their fading history. This form of education through environment is a new trend in landscape design and development and is supplementing or even replacing lawns, swing sets and sandboxes with sources of education, entertainment and commerce. Ultimately, it may be that these projects will change what we think of when the word “park” come to mind. — M.H. |

The area under development had originally played host to manufacturing and industrial operations. In fact, the entire housing tract was replacing just three or four multi-acre plants that had long since been shuttered. This form of redevelopment has long had both supporters as well as detractors, but in this case – in my humble opinion, at least – it was a welcome change for the neighborhood.

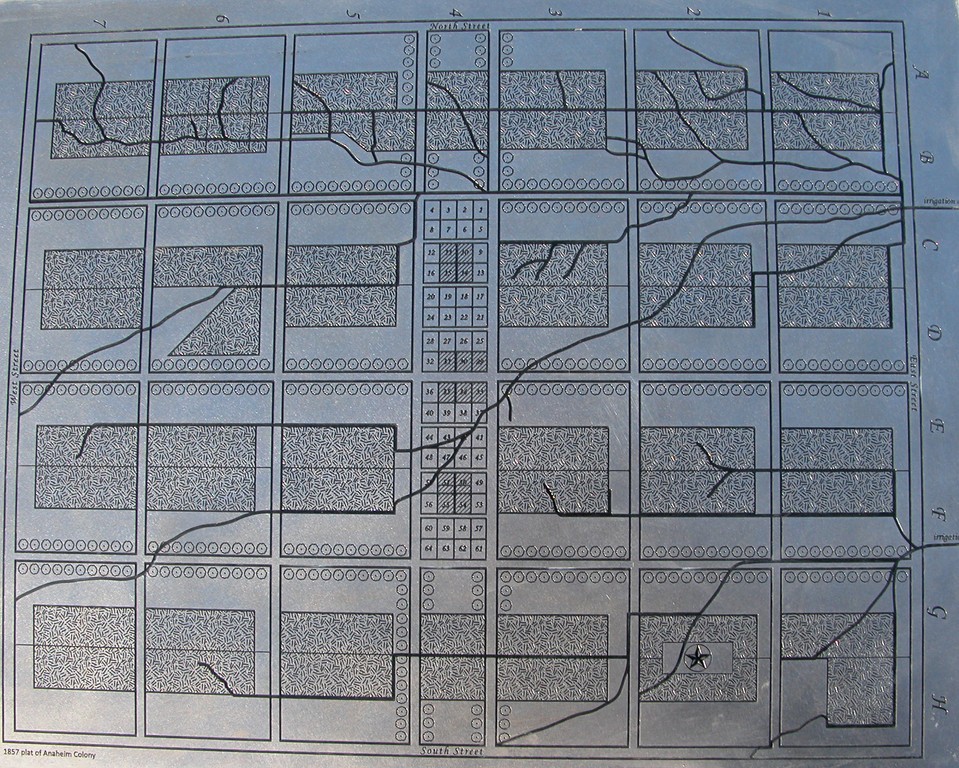

In the space set aside for the park, the trio had laid out a waterfeature that not only symbolized how the nearby Santa Ana River received its water, but also how the early settlers put it to use. Best of all, they’d found an old piece of parchment that showed the original layout of the city, including details of the irrigation channels and the organization of the vineyards. This ultimately served as a 1:100 scale model for the new park’s Water Court.

The watershape originates with the River Course and an abstract representation of the San Gorgonio Mountains that tower over the area and feed the Santa Ana River, which winds through San Bernardino and Riverside counties before reaching Orange County and the vicinity of Anaheim. This watercourse flows to a collection area reminiscent of the old trash-grate versions found in antiquated agricultural supply systems.

After this collection point, the watershape gets literal.

From that point on, in fact, the designers used the historical layout of old Anaheim gleaned from the parchment with just a very few twists. The old irrigation channels became either stainless steel runnels or blue sections of decorative concrete; original buildings were represented by colored concrete blocks; and the fields to be flooded by irrigation water became sections of wet deck. This space was bordered by inscribed versions of Anaheim’s North, South, West and East Streets, all of which still exist today.

It was at this point, where the concept was beginning to take real shape, that my firm was engaged to help the team develop practical approaches to the various water systems that would be needed to complete the project.

CAREFUL STEPS

To help ensure that everyone was always on the same page, Walker staged regular meetings of the entire project team, including landscape architects, engineers, builders, artists and representatives of Colony Park’s developers.

| Based on a document found in the city archives, this map – reproduced in etched stainless steel – depicts the original layout of the irrigation system as well as the parcels included in the community envisioned by the German and Austrian farmers who settled in Anaheim. This new park and its amenities celebrate that history – and introduce it to citizens who might be unaware of their city’s agricultural past. |

One early concern with this project was a fear that the original design might be perceived as an interactive waterfeature by local health agencies – an impression we wanted to dispel. As a result, we communicated frequently with directors of the county’s environmental health department and finally were invited to make a formal presentation in which we were to define and explain the nature of our project.

With further discussion and some minor design adjustments, the project was finally deemed to be “non-interactive,” which meant we could proceed outside their jurisdiction and without observing the legal constraints applied to interactive features. Even so (and for obvious reasons), we followed the rules observed by interactive waterfeatures with respect to water circulation and treatment.

|

Extended Time Frames Through the past dozen years, I’ve become accustomed to working on projects that spend multiple years in development. Some of these endeavors are so vast or sensitive or complex that immense amounts of time must be invested in satisfying municipalities or property owners and in figuring out all of the technical details in ways that will make the construction process as smooth and efficient as possible. One of the primary goals in all of this preparatory work is to minimize change orders. In the case of the Colony Park project described in the accompanying text, those changes were minimal and were the result of municipal requirements that snapped into place while the park was under construction. Ultimately, no more than a few hundred dollars was expended on such diversions during the course of a $500,000 project. Happily, tight programs typically translate to quicker construction – essential in this case because we had a firm deadline for completion. This led construction manager Ken Pease (with Brookfield Homes, Costa Mesa, Calif.) to hold weekly status meetings with all design and construction professionals, effectively tying up loose ends and ensuring smooth progress. This was all to the good for me, because from the outset I was a bit concerned that any of a hundred different details we wdere working with had the potential to derail or paralyze the entire program. To my great relief, Pease’s approach created an environment in which distractions were absolutely minimized. — M.H. |

As designed, the park’s water network drains by means of gravity to a subterranean, multi-thousand-gallon surge tank. Once there, the water is processed through a subterranean equipment vault before being returned to various feature points around the park.

Setting up the River Course was a simple matter, but the Water Court’s cityscape proved to be a real challenge because of the precise volumes of water that needed to flow steadily through the runnels and the equally precise volumes of water that needed to spread out across the wet-deck areas.

For starters, I calculated the flow rate for a half inch of water in a five-inch wide runnel using tried-and-true civil engineering calculations. These formulas, however, had been conceived for use with open channels of immense size, so I recognized a need for flexibility and establishment of multiple control points.

I also knew that there would be hours’ (if not days’) worth of field adjustment needed before everything would flow smoothly. To make this possible, we worked with a number of variable-speed pumps (Pentair Water Pool & Spa, Sanford, N.C.) as well as metered dump lines leading to the surge tank – all to allow for fine tuning.

The work on site proved to be equally challenging. Early on, I had joked with the design and construction teams that what we were doing was like building a fifty-foot-long piano on a deadline with the help of just a couple dozen people. There were countless slight tweaks to be made with the runnel installation and plumbing as we went along, and at the same time we had to work closely with the concrete contractors to make certain they could make their numerous color pours (using materials from Lithocrete, Costa Mesa, Calif.) in a safe manner.

Before long, what had been a joke about the piano became a somewhat nagging truth as we interwove and painstakingly pitched all of the runnels amid a network of forms and steel reinforcement. Even bonding was a challenge as we learned that everything had to be evaluated and considered prior to placement.

ARTISAN CONSTRUCTION

When we finally initialized the pumps, we were happy to see that we were fairly close to targeted flows. As expected, there were adjustments to be made with the pumps, valves and grating system, but before long, everything performed as we’d envisioned, with water erupting from the headwaters stone, the river raging and the collection/distribution system working just as we desired to flood each piece of “land” in the layout.

As I have professed countless times in WaterShapes and in my Genesis 3 classrooms, this sort of artisanal building produces results that I see as being far superior to product-based approaches to design and construction. Had we relied on product catalogs as our primary resources, this project would have never have come to such an artistic or reliable completion. Indeed, everything here involves unique, highly creative solutions to situations both simple and mightily complex.

Take, for example, the stainless steel runnels: Yes, we could have channeled the water through concrete, sections of stone or tile grooves, but the designers had determined that something more was needed: These symbolic arteries carried early Anaheim’s life blood, and our watershape needed to reflect, emphasize and celebrate their significance.

The environmental artists saw steel runnels as the best solution, so instead of buying components off the shelf or simply pouring some concrete, we needed to custom fabricate and etch stainless steel in configurations that precisely duplicated the water system laid out in the plans.

Although expensive and labor intensive, pursuing this approach produced outstanding results: The highly reflective surfaces and the detailed etching make these utilitarian components the stars of the show and, as intended, brings home the message about the importance of these waterways.

| The runnels (and blue extensions in decorative concrete) represent the original system of irrigation canals laid out by farmers who originally hoped to turn Anaheim into a complex of vineyards but who ultimately found orange groves to be better suited to the area. The parcels set aside in the core of the 19th-century community are embodied in the park by structures made from concrete blocks |

Of course, not every visitor to the park will know Anaheim’s history, which means we needed to include some signage explaining the park’s (and project’s) story. This led to inclusion of a laser-etched steel plaque explaining why such a complicated art piece has been installed for general public enjoyment. I have always favored use of this sort of signage, valuing them as roadmaps to understanding.

Art and watershapes can indeed be educational, and Lance Walker and his team have crafted a beautiful example of that concept here: Through careful design and coordination, every one of us participated in a process that will educate the community and entertain their senses for many years to come.

Mark Holden is a landscape architect, contractor, writer and educator specializing in watershapes and their environments. He has been designing and building watershapes for more than 20 years and currently owns several companies, including Fullerton, Calif.-based Holdenwater, which focuses on his passion for water. His own businesses combine his interests in architecture and construction, and he believes firmly that it is important to restore the age of Master Builders and thereby elevate the standards in both trades. One way he furthers that goal is as an instructor for Genesis 3 Design Schools and also as an instructor in landscape architecture at California State Polytechnic University in Pomona and for Cal Poly’s Italy Program. He can be reached at mark@waterarchitecture.com.