All About the Water

By Perry Wood, Mark Baker & Travis Tuck

By Perry Wood, Mark Baker & Travis Tuck

People who live in and around Hilton Head Island, S.C., cherish the memory of Charles Fraser, the visionary developer who set the standard for the way communities look along vast stretches of the Carolina coast. Most prominently, he pioneered progressive land-planning standards 50 years ago in developing Sea Pines, one of the first communities to incorporate environmental preservation as part of the development, take its design cues from nature and support the concept with land covenants and restrictions.

Fraser’s vision for Sea Pines has since become the foundation for many planned communities worldwide and embodies a philosophy that has, in the intervening years, spread throughout the country. Indeed, our firm – Wood+Partners of Hilton Head – has always endeavored to adhere to this approach in planning communities that are situated in and around natural environments.

Most of the time, that means we work (as Fraser did) with water as a central amenity, whether the setting borders a lake, the ocean, a river or a natural wetland area. As we see it, our mission is to preserve and, where we can, even enhance the presence of the environment in ways that influence the culture and character of communities that share these spaces with their surroundings.

Everything we do is steeped in the thought that nature and people can co-exist when the needs of both are allowed to harmonize. In fact, we like to say that we listen to the story the land tells us, and then base our designs on the opportunities and constraints it defines for us. Whether it’s a wetland, a forest, a mountainous area or someplace on the ocean, we find ways to value and preserve those settings and reconcile them with the communities we establish.

Although every situation is a bit different, our objective is always the same: We seek sensible ways to blend the two together.

PAPER PLACE

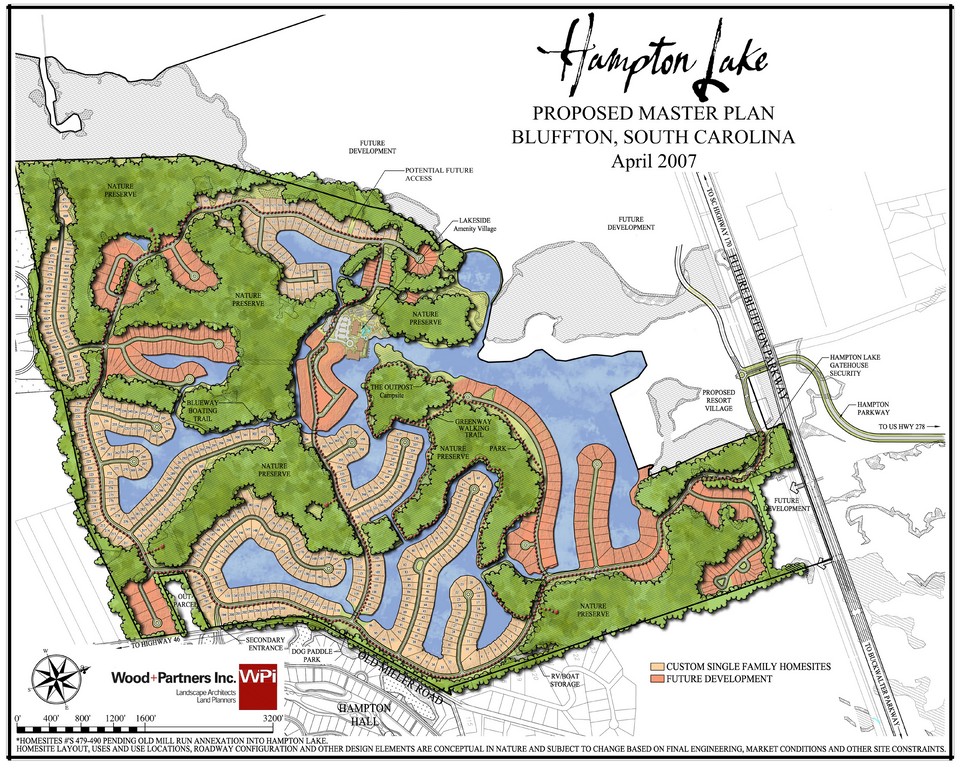

The Hampton Lake project we’ll be discussing here is a textbook example of this approach to land planning and development – one that’s probably unique within the greater Hilton Head Island community.

Where most of the communities on the island are organized around ocean or river frontage and are defined by proximity to large bodies of water, Hampton Lake is different in that it is located ten miles inland in the town of Bluffton, S.C. Before this project, none of the inland developments in this area featured any kind of interface with an aquatic environment – but this project changed all that.

The 900-acre site is part of the 4,500 acre Buckwalter Tract. The tract includes forest and wetland areas once owned by International Paper Co., which managed the land to generate pulp for its paper mills. The company sold the land to our client, John Reed, the owner and founder of Reed Development Co., who hired us in the mid-1990s to begin the process of preparing the area for development.

This parcel was a key component in Bluffton’s annexation of 50,000 acres of former commercial forest into the town proper – this at a time when its population included a mere 500 people. With the annexation, Bluffton overnight became the fifth largest city in South Carolina in terms of land area and has seen explosive growth since then, with 100,000 homes on board or in the planning stages and almost all of them in the area once controlled by International Paper.

| The intricacies of the space reflect our desire to maximize resident’s access both to the wetlands that grace the property as well as to the man-made waterways their homes overlook. While we aimed to encourage direct contact with and use of the lakes and channels, we needed to set distinct physical boundaries to separate people from the wetlands – and did so by setting up miles of paths and bridges that carry homeowners and their guests right up to the preserved areas without permitting any sort of intrusive access. |

As part of the process, community leaders established a number of guidelines related to land use and the preservation of natural areas. From the start, they’ve kept this focus on maintaining and responsibly using the area’s natural resources – principally meaning that all wetlands were to be preserved because of their critical role in processing stormwater runoff and maintaining water quality in local wetlands, rivers and waterways.

The work we do and our guiding philosophy made us a natural fit for the job. And it didn’t hurt that we were a local firm and that all of us are locals who have a personal interest in seeing the beauty of Hilton Head and the low-country area of the state preserved, celebrated and even augmented.

In analyzing the site, we found extensive wetland areas, but no river or ocean frontage. This led us to organize the community with an eye to a defined, 345-acre wetland reserve, but it also led Reed and the planning team to include a 165-acre lake with more than 15 miles of shoreline that the majority of the development’s 900-plus homes would overlook and which would host many of the development’s major and minor amenities.

This dual exercise in watershaping would enable us to preserve the wetlands while at the same time creating a desirably high standard of living for residents – a mixing of interests that we’ve always seen as being within reach when water is used in harmonious, creative ways. In fact, early planning led Reed to coin what would become the slogan for the entire project: “It’s all about the water.”

WETLANDS PRESERVATION

Application of that mantra began with the 345-acre wetlands.

In general, these areas tend to be low-lying and play key roles in accommodating the runoff from storms both major and minor. As such, they have non-sandy soils that are heavy with nutrients and play host to large varieties of plants supported by the near-constant presence of water. This means they sustain all sorts of wetland grasses and hardwood species – oak, cypress and maple – that flourish in wet environments.

The wetlands of coastal South Carolina also have their idiosyncrasies, including unusually complex physical configurations that extend from the fact that the land is very flat and the water table is extremely high – just a few feet below the surface. Typically, the total vertical difference from the highest point to the lowest in these areas is no more than four to five feet.

Given the flat terrain, these wetlands are configured in complex patterns in which fingers of shallow water area extend in web-like forms into the pine forest and tend to organize themselves around central drainage flows. It’s not exactly like the watershed for a stream or river, but with careful observation it’s nonetheless possible to perceive a general flow of water from one end of an area to the other.

| In setting up the edges of the lakes and channels, we used a number of approaches that define natural intersections between the wetlands and the open water – or, by contrast, establish spaces in which residents are encouraged to approach the water directly. In many areas, we set up broad littoral shelves that are crucial in maintaining natural filtration and keeping the lake’s water crystal clear. |

In this particular setting, we found ourselves in a place where dense pine forests on dry land were shot through with patches of old-growth hardwood and wetlands ecosystems. It’s a wonderful natural amenity that we knew could be preserved and even enhanced at the same time we could take full advantage of its presence in the development.

The trick, of course, is to achieve both aims without damaging the wetlands or compromising the quality of life in the human environment.

In this case, preservation was of particularly critical importance: In surveying the site, we discovered that these particular wetlands absorb runoff from a much wider area that the 900 acres with which we were concerned and were absolutely critical in providing natural filtration for stormwater and irrigation runoff flowing through the area and moving into the nearby May River.

Wetlands are invaluable in areas such as these because of their remarkable ability to absorb and process chemicals that are inevitably present in developed areas. As a result, our planning from the very earliest stages involved a tremendous amount of care and consideration of the way our community would interface with the overall area’s natural hydrology.

Before we could begin any development, in other words, we had to go through the rigorous rounds of civil engineering involved in configuring a drainage system that would effectively and efficiently distribute and treat runoff from developed areas.

HUMAN INTERFACE

The other task in preserving wetlands in harmony with communities has to do with designing places where man-made landscapes interface with unspoiled environments. The goal here is to create spaces where people can be near the wetlands and enjoy the natural beauty of their flora and fauna without disrupting anything.

One of the primary measures we employed at Hampton Lake involved deployment of “littoral shelves.” Basically, we shaped the lake so that it had depths of around eight to ten feet and then brought them up to broad, shallow shelves where the water is 12 to 18 inches deep adjacent to the shoreline. These littoral shelves were somewhere in the vicinity of 20 feet in width and were areas in which we planted a variety of grasses and other emergent plants.

By establishing these transitional shelves, we not only enhanced the physical beauty of the wetlands and lakes, but at the same time increased their ability to filter nutrients and sediments from the water before it could enter the primary flow pattern. In other words, because these areas could shoulder the burden of runoff from our developed areas, we effectively compensated for our intrusion at the fringes by increasing the wetlands’ ability to provide natural filtering and purification of any runoff.

| The lake is a place of great natural beauty, with much of its 15-mile shoreline bordered by wetland plants as well as native hardwood trees. Access to views is provided both by placement of homes as well as by the network of pathways that lead hikers to many of the best viewpoints. Also by design, the lake is meant for both wild and human contact: The birds have taken to the water in large numbers, as have residents who use nonpolluting electric-powered boats to get around. |

We used various edge treatments to stabilize and maintain the intersections of dry land with these littoral shelves. In some beach areas, for example, we installed bands of riprap along the edge. By contrast, in other areas where the pine forest meets the wetlands, we installed bands of lawn that can be mowed and easily maintained at the same time as we preserved some sections with natural woodland edges.

These treatments are meant to provide distinct visual and functional boundaries between what is wetland and what is surrounding dry upland area. Lawn or rock bands serve the dual purpose here of stabilizing the shoreline and establishing easily observed boundaries for human activity.

We also encouraged permissible interaction with the preserved environment by setting up a series of well-defined “wetland observation trails” that lead to a variety of scenic stopping points – and in some cases to boardwalks that move right through the wetlands themselves. The idea here: We want the wetlands to be available as a primary community amenity and bring residents and visitors into close proximity with its plant and animal life. We want them to enjoy the beautiful trees, the water’s reflections and various birds, fish, deer and even alligators – and do so in complete, non-intrusive safety.

In other words, this program serves our conservation mission by preventing disturbance of the wetlands and carefully controlling where people can and cannot go. For Hampton Lake, this has meant designing and installing more than nine miles of trails that give residents and visitors ample access to the wetlands – a contact we see as one of the primary benefits of being part of the community.

LAKE CRAFT

For all of the care with which we approached the wetlands areas of the site, the primary challenge we faced in the project was creating an environment in a dry pine forest that, from a real-estate perspective, would enable Hampton Lake to compete effectively with river- and oceanfront developments. Preserving the wetlands and providing access to them was certainly part of that program, but we had to take it several long steps farther.

The best way to do so, we thought, was to build a new lake that would provide shoreline spaces for residences as well as stretches we could dedicate to common areas and recreational amenities. (For a brief discussion of the lake’s construction, see the sidebar below.)

|

Digging In Building a 165-acre lake of the complexity of the one described in the accompanying article is no small task. First, all vestiges of the pine forest had to be cleared from the lake’s footprint – a task handled in conjunction with local lumber companies that bought, graded and removed the timber. Next, we removed and stockpiled the top 12 to 18 inches of topsoil. Laden with roots, mulch and a variety of other organic material, this soil was extremely rich in nutrients and was to be put to use as a soil amendment throughout the site. With that done, we brought in heavy excavating equipment to dig out the main body of the lake, stockpiling the spoils for use around the site or passing it along as fill to other developments in the area. In other words, nothing we unearthed in creating the lake – timber, topsoil or fill – went to waste. With the hole dug, we now had to deal directly with the fact that the water table at Hampton Lake was just a couple feet below the surface level. Our intention to create a lake that would be several feet deeper than the water table’s level engaged us in a massive dewatering operation – and also encouraged digging at breakneck speeds. Once we had the lake at the desired eight- to ten-foot depth, we contoured the banks, set up the littoral shelves and started planting grasses and other materials to stabilize the slopes. Next, we established the drainage structures: These allow water to flow out of the lake, into the nearby wetlands and, ultimately, into the river system beyond. The lake is fed using groundwater, which, because it is naturally filtered, means it has terrific water quality. But the lake is basically a self-contained system, so we help keep the water clear, clean and oxygenated with a series of subsurface aeration systems. As we see it, maintaining water quality is important not only to the residents who invest in a home at Hampton Lake, but also for the whole area around the development and the wetlands, streams and rivers influenced by our stewardship of the land and its resources. — P. W., M. B. & T. T. |

As the overhead view reveals, the resulting body of water is quite complex in layout: It features not only an irregular shoreline, but also a chain of islands and small waterways that all connect to large, primary thoroughfares. The role played by these various channels is so significant that we referred to terrestrial pathways as “greenways” while similarly referring to the systems of channels in the lake as “blueways.”

This complex configuration maximizes shoreline relative to the water’s surface area, which we thought essential. But it also creates a situation in which homes back up to the water and have small, private docks – a feature that has proved so popular that many residents are just as likely to travel from place to place by boat as they are to move about on foot or in their automobiles.

To be sure, the lake is man-made, but that says nothing about how well the planned community interfaces with its accompanying aquatic environment. In fact, its artificiality has key advantages in that the water level is controlled, so there’s very little of the fluctuation that you’d find in a tidal area or even in some natural lakes that might experience changes in water level as a result of storm surges or drought.

Given the reliability of the level, we were able to take full advantage of every available bit of shoreline in ways we couldn’t have done with a truly natural lake.

At one end of the lake, for example, the community’s amenities center has a series of docks and a large boathouse that has both covered and open-air dockage. There are boats for rent here, as well as slips for privately owned watercraft – and there’s never any worry about anyone running aground as a result of rising or dropping water levels.

There’s also a campground on another part of the shoreline that residents and visitors can approach either on foot or by water. There are all sorts trails and paved walkways that meander through the lakeside area, all organized around key viewpoints out over the water. Again, it’s all part of our program to bring residents and visitors within easy proximity of the water.

It’s important to note that all of the boats on the lake are electric-powered. First, the environmental standard we’re working with is all about minimizing harmful chemicals in the water, so keeping gasoline, exhaust and other pollution out of the picture is important. Second, the electric-powered boats, some of which are quite large, move at a relaxing pace with minimal wakes, lending themselves to the developer’s desire to banish loud, fast-moving watercraft and the safety issues that accompany them.

THE COMMUNITY’S HEART

By combining a comfortable, engaging, community-oriented lifestyle with easy access both to the lake and the nearby wetlands, we’ve brought real meaning to the “It’s all about the water” tagline: It’s more than a marketing bromide; instead, it’s a genuine description of what it’s like to be here.

Completing the picture is Hampton Lake’s Lakeside Amenities Center, which overlooks one end of the lake and features a number of facilities available to residents, including buildings housing a workout center and a multi-use indoor community center.

Outdoors in the same vicinity, we set up a resort-like environment featuring a range of aquatic experiences for all ages. On one end, for example, is a large play area for children with an array of dry-land play structures as well as shallow-water play areas outfitted with dozens of interactive features – sprays, wet umbrellas, leaping jets and slides.

The shallows transition into a primary swimming area for adults and older kids. It has a meandering, curvilinear, free-form design and includes a variety of underwater benches and a broad water-lounging/deck area – just the features you’d expect to find in a luxurious, high-end resort. To one side of the pool, there’s a massive deck/island that creates a lazy-river passage that moves under a large bridge and rolls by sunbathing areas.

| The Lakeside Amenities Center overlooks the water and serves not only as a community center but also as a general resource for fun of the sort you’d expect to find at a high-end resort. With ample dockage, beaches, shade structures, pools, spas and decks – not to mention a lazy-river feature and ample wet and dry play areas for children – the center offers many types of recreation while blending in beautifully with its waterfront setting and forested surroundings. |

Also, tucked away in a quiet corner of lakeside area (adjacent to a sandy beach) is the “adults only” pool. This serene environment features a separate free-form pool with underwater benches, shallow wading areas and umbrella-shaded decks and cabanas.

The program here involved seamlessly blending water, decks, landscaped areas, pathways and picnic areas into a free-flowing composition in which everyone has easy access to different types of recreation. That all of this works into the “all about the water” theme is no accident, right down to the safety-surfacing material chosen for the play area – a set of swirling blue and white shapes that are intended to represent moving water.

Hampton Lake has been a project of such scale and complexity that our firm expects to be involved on site for years to come. Our client deserves tremendous credit for approaching the development with the highest ideals of natural preservation on one hand and quality lifestyle on the other, with everything aimed at providing a residential area that adds real value to the region in more ways than can easily be counted. We look forward to building on a relationship that has, so far, produced exactly the results we’ve all been seeking.

Going forward, we’re proud to have participated in a project that embodies such a progressive ethos and have been happy to see the principles we’ve applied being picked up and used elsewhere. When design firms and developers look for examples of properties that represent the best of environmental stewardship, we’re hoping Hampton Lake will be a place that pops into mind for years to come.

Perry Wood is founder and president of Wood+Partners, Inc., a landscape architecture and land planning firm founded in 1988 that now has offices in Atlanta, Hilton Head Island, S.C., and Tallahassee, Fla. Wood is recognized as a leading authority in land planning, landscape architecture and urban design as well as zoning and land-use law. He has participated in a broad spectrum of project types for private and public sector clients, ranging from 15,000-acre community master plans to urban designs, streetscapes and community parks. Throughout his 28-year career, he has practiced and applied environment-based planning with an emphasis on “smart growth” and environmental preservation and stewardship. Wood earned his degree in landscape architecture from the University of Georgia and serves on the National Council of Landscape Architectural Registration Boards. Mark Baker is a partner at Wood+Partners. He began his career on Hilton Head Island in 1977 after receiving his landscape architecture degree from the University of Georgia. He later moved to Charleston, S.C., where he served as the director of land planning for a large architectural firm. In 1998, he returned to Hilton Head Island to form a partnership with Perry Wood. Recognized as a leading authority in community planning, parks and recreation planning, resorts, urban design and urban redevelopment projects, he has undertaken projects throughout the southeastern United States and the Caribbean. Baker is also active in his community and profession and currently chairs the Environment, Park and Recreation Subcommittee of the Greater Island Committee. Travis Tuck is a graduate of the University of Georgia’s School of Environmental Design and specializes in community planning and amenity-center design for Wood+Partners.