A Stone Primer

In one form or another, almost every landscape project uses stone. Whether it’s ledger, rubble, pebbles or flagstone – on its own or woven into other hardscape materials – when it comes to shaping exterior environments, stone is one of the most versatile of all materials at your disposal.

In my experience as a stone supplier, however, few landshapers understand enough about the properties and characteristics of available stone products to use them as effectively as possible. This is true despite the fact that inappropriate stone usage creates liabilities for both the installer and the client and that the need for eventual replacement incurs great cost down the line.

Simply knowing which types of stone are dense and which are soft, for example, is enough to prevent many problems with installations and will make landscapes more successful. While placing beautiful slate on an exterior deck may seem a great idea visually, for instance, it will eventually disintegrate as a result of exposure to the elements, nobody involved will be happy – and everybody will recognize that it would have been better to use a stone capable of holding up under the same circumstances.

With that in mind, this article will discuss, compare and contrast the various categories of stone, the aim being to help designers think through and make proper choices and guide installers who need to know the materials they’re working with in order to do a better job in serving both designers and clients.

PRIMARY CONSIDERATIONS

When landshapers come to visit us at Malibu Stone & Masonry (Malibu, Calif.), they typically have something in mind for their projects. No matter what, however, my first question is about what color stone they need.

Color is, without exception, the driving force behind all other decisions about stone – and it immediately limits the range of choices. The design task may involve matching a color on the architecture of the home or picking up a hue or tone found prominently in the landscape or some other key design element. Whatever the impulse, color almost invariably points us in a particular direction.

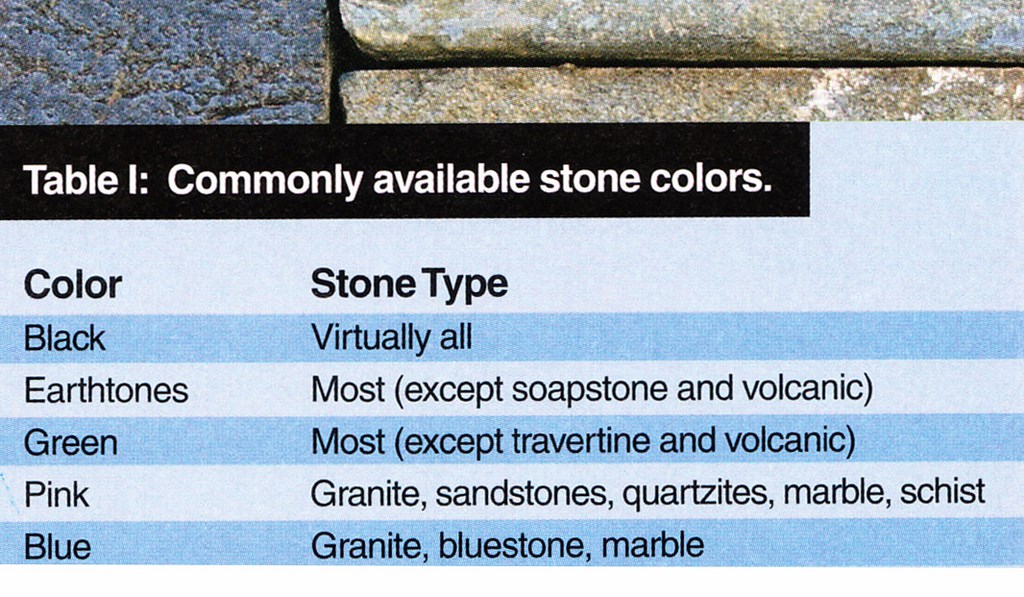

In my discussion with landshapers, I always have the information in Table I in mind: Thus, if someone comes in looking for a blue-colored stone, I quickly know that the palette will be limited to granite, bluestone and marble. If, by contrast, the need is for a black stone, I know I can find something in virtually every category. Although most stone has a mix of colors within each piece, there is typically a predominant tone for us to discuss right off the bat.

In my discussion with landshapers, I always have the information in Table I in mind: Thus, if someone comes in looking for a blue-colored stone, I quickly know that the palette will be limited to granite, bluestone and marble. If, by contrast, the need is for a black stone, I know I can find something in virtually every category. Although most stone has a mix of colors within each piece, there is typically a predominant tone for us to discuss right off the bat.

Another insight I bring to the conversation is an experienced awareness that a stone’s color may vary depending upon the way the material is cut or broken. When clean cut, for example, a quartilitic sandstone such as Malibu Sunrise shows no color on its side edges. When Apache Cloud (a schist) is broken or chiseled, however, it shows variations on its top surface as well as on the fractured edges.

Most landshapers know, of course, that stone can take many forms: rubble, pebbles, cobble, ledger, flag, blocks and slabs. You know it can be made smooth to various degrees by saw-cutting it and then putting it through a polishing, sandblasting, honing, flaming or tumbling process – or that it can be left with a smooth but more natural appearance using natural-cleft or split-face techniques.

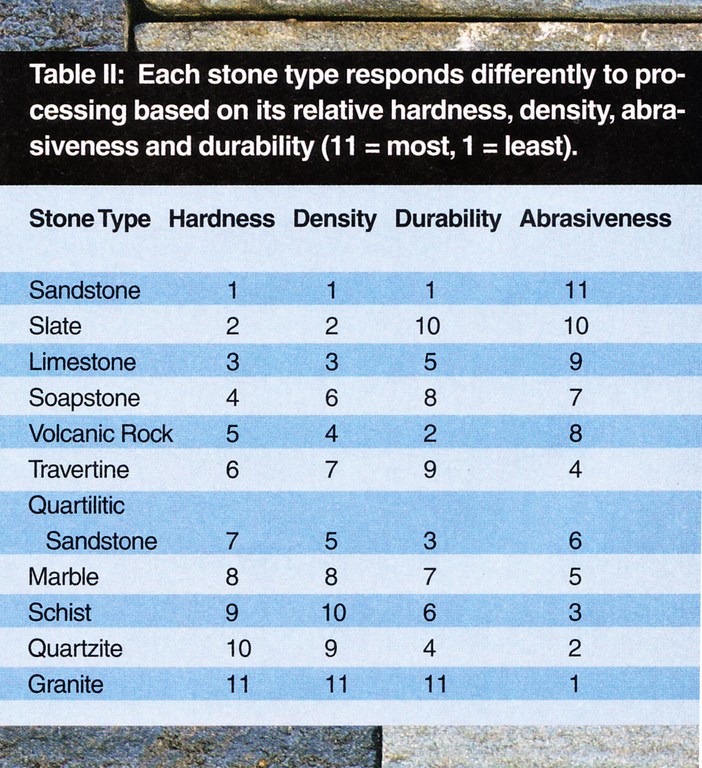

Each type of stone takes differently to the processes of producing those forms and appearances as determined by the individual type’s relative hardness, density, abrasiveness and durability (summarized in Table II). Armed with this standard information, you can begin to understand which stone types are best suited to being treated to achieve particular looks – or why they should be fabricated only in certain forms.

Each type of stone takes differently to the processes of producing those forms and appearances as determined by the individual type’s relative hardness, density, abrasiveness and durability (summarized in Table II). Armed with this standard information, you can begin to understand which stone types are best suited to being treated to achieve particular looks – or why they should be fabricated only in certain forms.

IN THE QUARRY

Those four factors (relative hardness, density, abrasiveness and durability) generally dictate the ways in which stone is quarried. Harder, denser materials such as marble, for example, are cut out in giant blocks rather than as flagstones.

With painstaking effort, of course, you might be able to form a marble block into flags by breaking it, but the resulting product won’t look like typical flagstone. You might also impose a chiseled-edge look on marble, but that’s an odd request that results in an appearance that’s not particularly desirable. The fact is that marble is a very solid material that simply doesn’t lend itself to this type of shaping.

| With few exceptions, color is the determining factor in stone selection. If they don’t already have something definite in mind to get the selections process going, our displays help designers and their clients work through a wide range of possibilities. |

Most of the denser/harder stones are quarried as blocks with smooth surfaces. These include travertine, soapstone, marble and granite. By contrast, softer, less-durable materials are quarried using a chisel, bar or other machinery that is not intended to produce a smooth-surfaced material. These types of stone (including quartilitic sandstone, schist and quartzite) are chiseled in layers rather than in blocks and have uneven edges.

There are, of course, some materials that aren’t classified so simply: Limestone and sandstone, for example, can be quarried either in blocks or by layers, while volcanic stone – a true oddball among stone types – is harvested as it lays in the field.

|

Decomposed Granite Decomposed granite is, as its name suggests, a byproduct of granite – essentially a slab that has been exposed to the elements for thousands of years and eventually begins decomposing and disintegrating and is ultimately crushed into a sand-like substance. This inexpensive material is used primarily for pathways and is great for flat-surface applications where no plants will be grown. It’s a porous material, but it compresses to become a hard surface that prevents weed and plant growth. — J.N. |

Once the color decision is made and the range of possibilities has been whittled down a bit, it’s time to consider the specific application for which the stone is intended – where and how it will be used, whether it will be in or out of water and what texture is desired. If the material is to be used near a pool, for example, we know immediately that only certain stones will work.

I won’t list all possible applications and define the appropriate stone for each; suffice it to say that having an understanding of how the stone will be placed in the landscape or hardscape, whether it will be walked upon (or not), whether it will be directly exposed to the elements (or not) and, in short, whether any of a dozen other issues related to application are part of the picture (or not) will all combine to isolate the best stone for the job.

FINISHING THE PICTURE

To speed the selection process, the information and photographs below aim at giving you enough information about the fundamental characteristics of stone in each of the key categories to help you make basic decisions and narrow choices down yourself before you visit a stone supplier. It’s not that we don’t want to help: It’s a matter of streamlining the process so you can focus on design or installation issues rather than spend time shopping randomly for stone.

Once the appropriate stone has been selected for your project, it’s also important to consider – before installation begins – whether the material will need to be sealed or not and, if yes, what type of sealant will be required.

| The way stone is prepared (or not prepared, in some cases) has a lot to do with appearance. Again, we help with displays that show stone in various finished forms, from the rough faces of cobbles (left) to a variety of other textures that can be used either separately or in blends (right). |

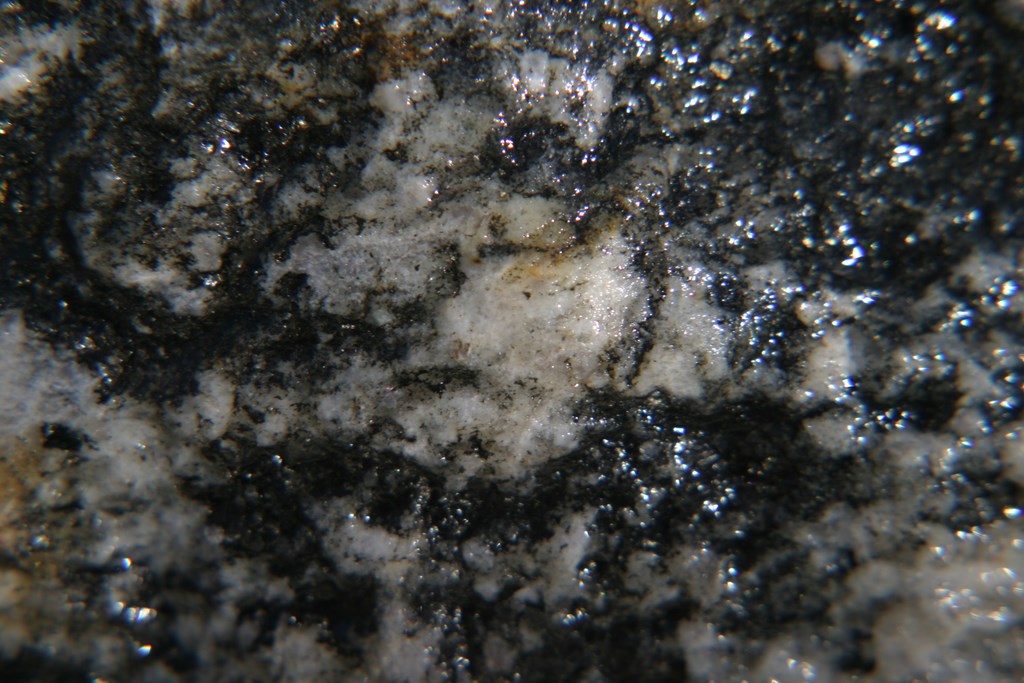

One of the great misconceptions about stone is that it doesn’t usually need to be sealed: Even though it looks like it has an impenetrable surface, for example, polished granite should be sealed to deal with the many fractures and crevices in its surface. This is why I consider sealing to be one of the most important aspects of any stonework job – and a future maintenance consideration as well.

The key is to determine what you’re trying to seal out. If the stone’s on an outdoor kitchen, for example, the concerns range from grease and oil to heavy traffic and maybe a sprinkler system. Then there’s appearance: Are the clients interested in holding the initial look, or do they want to make it brighter or different? Sealants are available in variations designed to do everything from simply protecting the surface to altering its appearance in subtle or not-so-subtle ways.

|

Rust Rust appears where there are iron deposits in stone – anything from a small piece to layers of material contained within the stone. These deposits are found in almost every type of stone (excepting soapstone, travertine and volcanic rock), and it can appear anywhere in the material. Stone is porous, so rust leaches out to the surface when exposed to the elements – particularly water or sun. There is nothing anyone can do to prevent its emergence, and in some cases there’s no choice but to replace a given piece of stone. The best practice is to inform clients of the possibility up front so there are no surprises down the line. — J.N. |

Always, however, the main reason to use a stone sealer is to improve the material’s longevity. No matter the stone type, a good sealant will always increase the usable lifespan of the stone and in many cases will enhance its appearance – depending, of course, upon the look you’re trying to achieve.

I also suggest hiring a specialist for stone sealing: Not only will this person apply the material correctly, but he or she will be completely informed about options and which products are right for which jobs. There are also codes and laws about the use of stone in certain applications: If you use marble or another slippery stone in a commercial application, for instance, there may be Americans with Disabilities Act rules that must be observed with respect to slip factors. An expert will know what to do and get the job done in a way that eliminates concerns about liability.

Here as in all circumstances, the more you know about the materials you’re working with, the better you’ll be at using them in the right ways. Being creative is a good thing, and many spectacular innovations have sprung from the minds of those who’ve used materials in situations nobody else has considered. But the only way to make stone work in any context – bold and imaginative or simple and routine – is to understand the characteristics and properties of each variety at your disposal and make the right choices based on what you know.

Let’s take a look at the basic characteristics of common stone types, moving through them alphabetically.

Granite

Uses: Primarily countertops or heavily trafficked areas; mostly indoor applications where exposure to the elements is an issue

Sources: Worldwide

Appearance: Crisp, modern-looking material with smooth surfaces

Forms: Slabs, blocks

Advantages: Cool surface; can be cut into strong squared or otherwise molded edges

Disadvantage: Unless flamed or treated to reduce slip hazard, not good for exterior traffic areas

Comment: Can be polished, honed or flamed.

Limestone

Uses: Wide variety, including interior and exterior countertops and decks

Sources: Midwest, Texas

Appearance: Flat/matte surface

Forms: Predominantly blocks and slabs but also various flat-surfaced shapes

Advantage: Cool surface

Disadvantage: Tends to chip easily

Comment: Fairly inexpensive

Marble

Uses: Not good for outdoor applications (too slippery); used primarily indoors

Sources: Worldwide, with best known supplies in Italy

Appearance: Smooth surface

| Modern Methods

Many machines and techniques are available to create stone surfaces and shapes for a wide range of applications. The most common are: [ ] Diamond saws, with blades that produce the smoothest possible surface. [ ] Stone guillotines, which provide for more controlled breakage but result in rough surfaces. [ ] Stone chisels, which result in a hand-hewn, hand-worked appearance. [ ] Stone splitter machines, which create a more rugged surface than a guillotine and offer a hand-hewn look.— J.N. |

Forms: Blocks, slabs

Comment: Commonly used in statuary and fountains

Quartilitic Sandstone

Uses: Highly versatile

Sources: Pennsylvania, New York, Tennessee, Oklahoma, Texas, Arkansas

Appearance: Lightly textured surface

Forms: Quarried in layers and blocks; available as flagstone or cut in a variety of shapes

Advantage: Can be flamed, honed or polished

Disadvantage: It’s everywhere – a bit overused

Comments: Highly reliable, widely available, inexpensive – a great value

Examples: Bluestone, Malibu Sunrise, Chapparal, Four Rivers, Malibu Gold

Quartzite

Uses: Limited because of density and hardness

Sources: Idaho, Utah

Appearance: Rough texture

Form: Flagstone

Advantage: Very thin and hard, making it good for rustic pathways

Disadvantages: Abrasive; dense/hard nature makes it expensive to cut – and results are generally poor

Comments: Inexpensive when used as flagstones; not good for large areas as single pieces are typically plate-sized

Example: Idaho Quartz

Sandstone

Uses: Wide variety, but most popular as flooring

Sources: Arizona, Colorado, Tennessee, California

Appearance: Similar to a roughly sanded concrete

Forms: Rubble, block

Advantages: Cool surface, so good around pools or on decks; wide availability; lots of sizes and shapes; quite inexpensive

Disadvantages: Not very dense; lifespan of about 25 years in deck applications

Comments: Can be used in place of travertine to reduce costs. Good for applications where great longevity isn’t needed. Some people like the look that comes from long-term wear and tear and chipping resulting from its soft nature.

Schist

Uses: Walls (ledgered or flat)

Sources: California, Connecticut, Utah, Idaho, Arizona

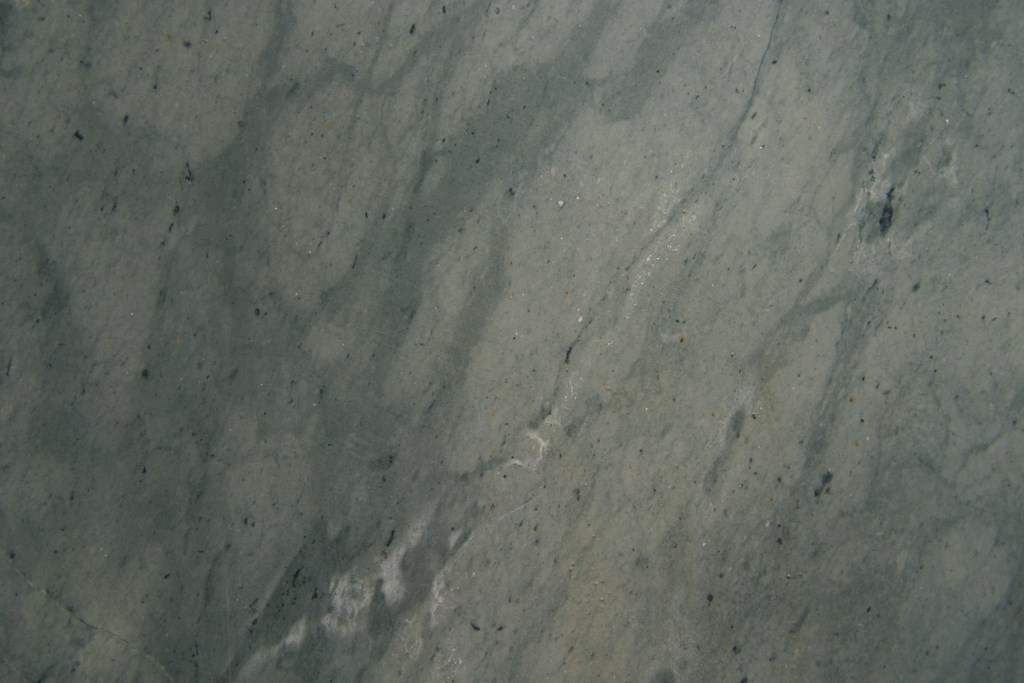

Appearance: Fairly flat, but has irregular surface and edge textures

Form: Quarried in layers

|

Finishing Techniques Different finishing techniques offer a variety of looks for completed stone surfaces, and the more versatile stone types can be finished in a number of ways. Granite, for instance, can be polished, honed and flamed. When polished, a shiny, smooth surface results, while honing roughs up the surface to produce a matte finish on a relatively smooth/flat surface and flaming, in which a cutting torch is applied to the surface, results in a much more rugged (but still flat) surface with small, exposed pits. — J.N. |

Advantage: Provides great wall textures

Disadvantage: Contains mica (a tight-grained, sand-like mineral), which makes controlling cuts difficult.

Examples: Bouquet Canyon, High Desert, Apache Cloud

Slate

Uses: Most flat surfaces

Sources: United States, China, India

Appearance: Shiny/flat surface with layered ridges

Form: Layered

Advantage: Only material that offers a shiny surface in darker-gray tones

Disadvantages: Highly susceptible to flaking; not recommended for outdoors because of slip factor; expands and contracts between layers when exposed to nature, resulting in flaking and surface pops; not good with radiant heat systems

Comments: It’s generally inexpensive, but slate is made up of layers of unfused shale and mud and has no strength or solidity; best for interior applications where it’s not exposed to the elements; should be sealed

Soapstone

Uses: Mostly countertops, thresholds, bathrooms, kitchens and indoor environments, including pizza ovens

Sources: Vermont, Scandinavia

Appearance: Flat, steel-gray surface, mostly monochromatic

Form: Mainly in blocks

Advantage: Very heat resistant

Disadvantage: Has talc that comes off on hands and clothing

Comment: Needs to be oiled

Travertine

Uses: Quite versatile – mainly pool copings, interior applications and flat/smooth surfaces

Sources: Worldwide, with Roman travertine the most famous

Appearance: Smooth surface

Forms: Blocks, flags (but hard to get as flagstone)

Advantage: Can be sawn, honed, polished

Disadvantage: Overused

Comments: Unusual in that when it gets wet, it becomes less slippery

Volcanic Stone

Uses: Primarily limited to fireplaces, firepits, veneers

Sources: Hawaii, Mexico

Appearance: Rough and craggy

Form: Rugged rubble shapes

Advantage: Can be used in firepits

Disadvantage: Not a lot of colors to choose from

Comment: Machines are now available that allow it to be cut

Joe Nolan is vice president and co-founder of Malibu Stone & Masonry Supply in Malibu, Calif., a construction wholesaler specializing in decorative stone products. Following several years as a construction superintendent for a general contractor, Nolan began his career in the stone business in 1985 when he went to work in sales for a masonry retail and wholesale supplier. Recognizing a large void in the decorative stone supply business, Nolan and co-founder Scott Armstrong established Malibu Stone & Masonry Supply in 1997.