A Sense of Participation

In his 1980 book, The Social Life of Small Urban Spaces, William H. Whyte described seven elements needed to make urban spaces successful: seating areas, ready street access, sun, the availability of food, the presence of trees, features that promote conversations among strangers and water – particularly in the form of water features and fountains.

As an example of this formulation, there is no more illustrative space than New York’s Paley Park: Completed in 1967 by Zion Breen Richardson Associates Landscape Architects & Planners, this pocket park is located in the bustling heart of midtown Manhattan and is often cited as one of the finest urban spaces in the United States. At a modest 4,200 square feet, the park is an oasis marked by careful use of airy trees, lightweight furniture, water and simple spatial organization – the key being the 20-foot-high waterfall spanning the entire back of the park.

The cascade provides a backdrop of white noise, its flow of 1,800 gallons per minute masking the hubbub roiling beyond a space hemmed in by walls on three sides and by an ornamental gate on the fourth. The walls are covered in ivy, and the overhead canopy is formed by honey locust trees – plantings that contribute a sense of serenity. The ground surface consists of rough-hewn granite pavers that roll out past the gate and flow all the way to the curb.

As Jan Gehl wrote in New City Spaces (2003), planners of today’s healthy cities recognize the value and importance of including parks of this sort for social and recreational activities. Combining his train of thought with Whyte’s, we at Crystal Fountains (Toronto, Ontario, Canada) see modern water features as the beating heart of these emergent healthy spaces – a point we’ll demonstrate in this pair of articles.

IN THE BACKGROUND

From our perspective, an elevated, elevating role for urban water means that fountains must evolve from idea into reality in a process we see as being aided by three distinct “engagements,” first in a pre-design phase with stakeholders; next through the design team; and, finally, with the design outcome and public interaction with the completed project.

The first stage may best be described as one of inventory and analysis – a time when the assembled project team steps back and focuses not only on the site, but also on the stakeholders. This is a time when, frankly, we thank 3M for having invented Post-It Notes, because they’re a huge part of the process despite the ubiquitous presence of computers.

To quote Jan Gehl again from the book noted above, “most urban improvements are carried out or at least initiated by visionary individuals or groups.” That was certainly true for Paley Park, and it was just as true with Berczy Park Fountain, designed by Claude Cormier + Associés and completed in 2017 in league with Toronto’s city council and the mayor’s office.

| By day and night, New York’s Paley Park is among the most revered of urban parks. In a compact space, it gives everyone who enters a welcome sense of calm in the heart of a bustling metropolis. It’s also an example of the levels of participation – by the city, the corporate sponsor and various development committees – required to get these projects on track.(Photo at right by Stechouse|Dreamstime.com) |

The project, which was aimed at renovating and revitalizing an existing park, was initiated by Toronto’s 8-80 Cities, a nonprofit organization whose mission is to “create safe and happy cities that prioritize people’s wellâ€being.” That group and its network of local collaborators spent nine months defining unconventional community engagement techniques and ultimately produced a report in November 2012 called “Make a Place for People.”

Claude Cormier + Associés won the subsequent design competition in March 2013, sparking a formal design phase that ultimately led to a construction process that began in September 2015. The project was completed nearly two years later and now includes rows of trees, a garden and benches along with the fountain.

| Toronto’s Berczy Park and its dog-themed fountain is another example of a grand urban collaboration – a participatory exercise in which government, civic organizations, artists, designers and local citizens rallied around a project that encompassed their diverse inputs and enabled all stakeholders to buy into and enthusiastically accept the outcome.(Photo at right by Typhoonski|Dreamstime.com) |

Moving from idea to completion involved a large and changing cast of characters drawn from 8-80 Cities, the city government, the provincial government, a local business-improvement group, park volunteers, the design team and the consultants, suppliers and installers they brought into the process – including the above-mentioned Jan Gehl as well as Dan Euser Waterarchitecture (DEW). It goes without saying that the early design discussions involved a broad range of personalities and interpersonal chemistries.

In true committee fashion, the local stakeholders generated their 60-page report to guide the energies of Cormier and his staff, whose task was one of translating the committee’s wishes into an actual master plan that reflected the report’s consistent ambition to produce a human-centered environment woven around a crucial water element – that is, a massive, three-tiered fountain structure highlighted by 27 cast-iron dog sculptures along with one large bone and a single, preoccupied cat.

This fountain is where DEW became particularly involved in the project – and where a second layer of engagement and participation surfaced as the fountain-design process moved forward.

A WORKING TEAM

It’s important to note at this point that technological advancements and innovative thinking are driving the watershaping industry in new directions and off onto new frontiers. For us at Crystal Fountains, this has seen the overall improvement of our participation in the creative process as fountain designers and engineers: We now get involved earlier and are more integrally engaged than ever before.

And it’s not just on the jets-and-pumps level: At one point in the not-too-distant past, refined modeling technology wasn’t part of our presentations; now, however, we have access to physics-based software we’ve developed that enables us to help our clients visualize results and sheer fountain physicality far earlier in the design-development process, right down to such details as splash factors.

That’s pretty cool, but it’s just part of a larger story of the several ways in which we as fountainers have been able to improve and speed the journey from concept to construction.

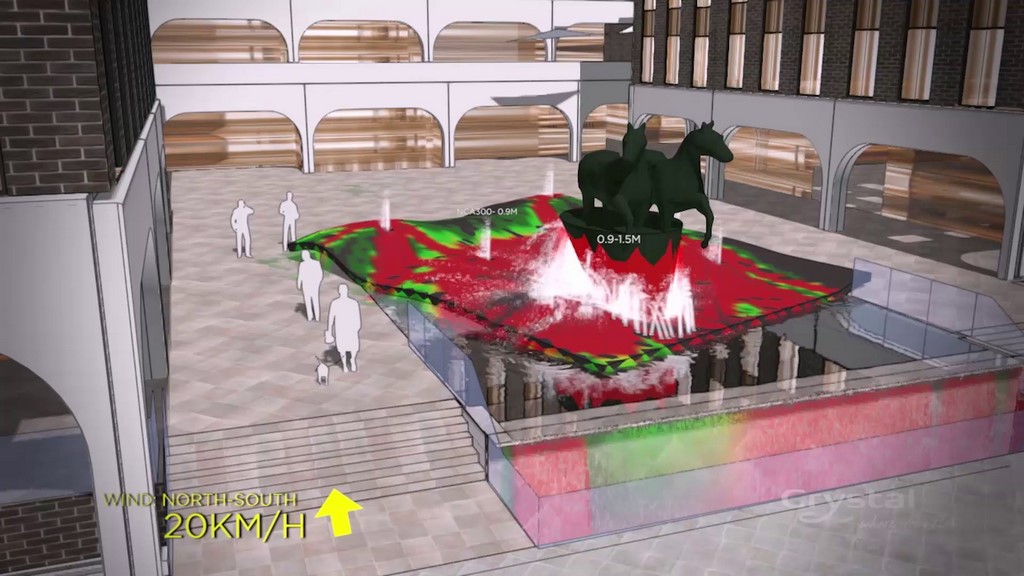

| Technology has become art’s necessary partner, helping fountain designers envision results right down to such key details as wind exposure, splash zones and a range of physical influences as a design develops. A modeling system such as this one helps everyone – from a mayor or a maintenance superintendant to a fountain installer or a future park user – visualize and understand a design proposal before anything starts taking real shape. |

It helps that, at root, we see the design process as a team sport in which the key is the sharing of a variety of experiences and knowledge bases, the combination of which strengthens the creative process and broadens the foundations for idea formation. This is why, in our own shop, we draw on the diverse perspectives of architects, landscape architects, industrial designers and graphic designers as well as mechanical, electrical and robotic engineers.

As specialists within this environment, we value working within a larger team that encompasses all of these backgrounds and disciplines. After all, when items under discussion include possibilities as distinct and diverse as LED lighting technology, advanced control systems and turnkey user interfaces, the simple fact is that our credibility and value on the team depends on other members being able to comprehend what we’re saying!

We embrace this outreach process ourselves, actively recruiting beyond our four walls to keep our own deliberations fresh, active, open and energetic. Sometimes this means new hires; other times, it’s about bringing in students from local design and technical colleges for a semester’s participation on our internal teams. At the end of the term, they present ideas and inventions – and get feedback and class credit in the process.

| Building a sense of communication and engagement with local technical and creative communities is an increasingly important component of our own design process. We work with students in our shop, for example, offering course credit while benefitting from their fresh creative input. We also teach in local colleges, host symposia and more – whatever we can do to participate with artistic, creative and technical forces in our community. |

We engage college faculty, too, particularly from the engineering disciplines but also from various design disciplines. And it’s a two-way street: We return the favor of their involvement by sending our staff out to lecture and teach in classroom settings and have systematically created networks that cast benefits in all directions. In one instance, for example, engineering professors helped us establish a specific, safe water velocity for interactive fountains, defining a 20-feet-per-second rate we now apply in our design work.

This visibility among outside groups allows us to keep in touch with young, artful minds and maintain relationships with their mentors – a great and rewarding form of community outreach and involvement that enables us to challenge our basic assumptions while collaborating within a greater creative community.

This is why artists have long been part of our world: They confront norms and push the envelope in ways that make us better at what we do. This is also why we bring in watershaping experts and consultants and host conferences and symposia on fountain technologies, techniques and issues. All in all, it’s a determined effort to keep up and steadily refine our approaches to the increasingly stimulating and challenging tasks at hand.

BASES FOR GROWTH

In addition to people power, we use innovative tools to advance our design work and make it easier for those outside our own team to understand and work with our ideas and make overall outcomes more predictable.

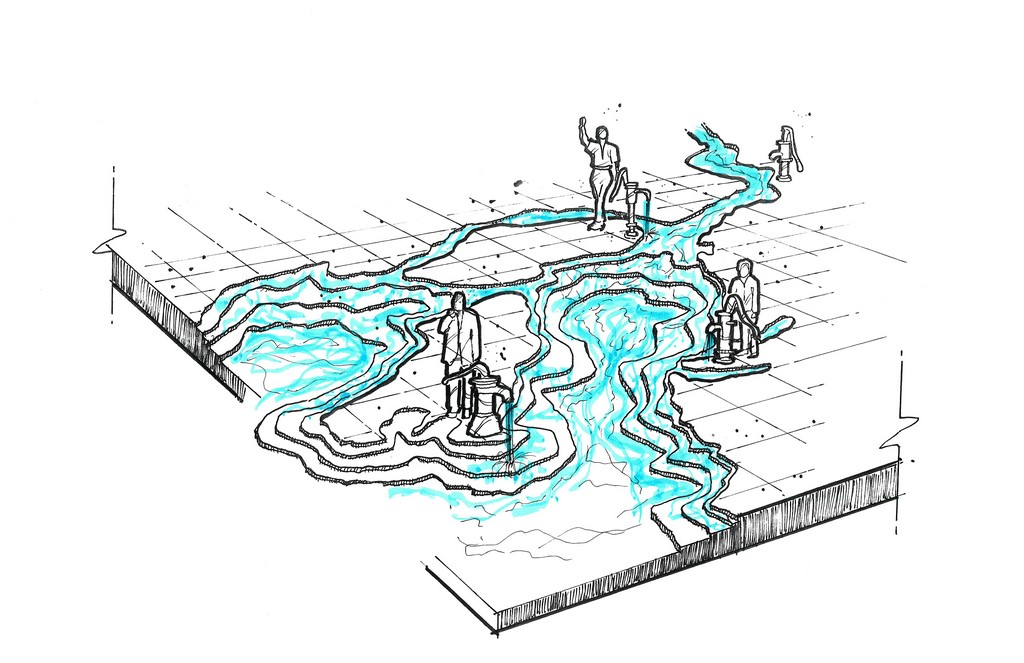

Internally and as was mentioned above, we’ve developed what we call WATERlab, a simulation software that allows us to explore more ideas, more rapidly and in more meaningful ways during the design phase. This is important, because the very nature of fountains and interactive water features have traditionally made them difficult for most non-watershapers to visualize – and even for some watershapers as well!

| We used our computer-modeling system to its full potential in developing waterfeatures for the Henry Doorly Zoo in Omaha, Neb. Our ability to anticipate splash zones, for example, helped us communicate about such details as basic spatial relationships and traffic patterns well before work began on site – a critical factor once again in gaining support of all of the stakeholders involved in green-lighting the project. |

We initially used this SketchUp-based simulation tool to verify which products created the most realistic effects when it came to suggesting, say, the breaching of a whale through the ocean’s surface – a task we faced in developing systems for the Alaskan Adventure waterpark at the Henry Doorly Zoo in Omaha, Neb.

Soon, the system began proving its worth beyond the initial design stage: Once construction is under way, we’ve now extended our use of the program to help choreograph the interactive water and light programs as well as anticipate real-world splash distances.

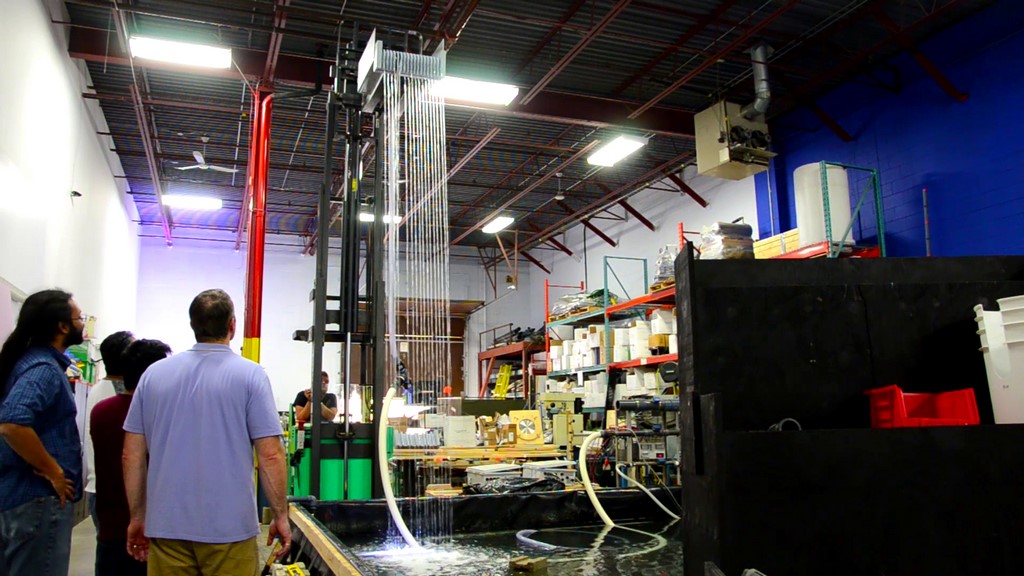

| While computer modeling is a wonderful asset, in many (if not most) cases there’s still also a need to develop mock-ups and prototypes, basically to test out systems and technologies and gain tangible evidence that a project is headed in the right direction. Whether it’s checking out a novel nozzle configuration or assessing the sound a droplet of falling water makes when it hits a cymbal placed far below, this is very often a necessary step – and another situation in which a broad group of stakeholders (from artists to citizens) get to see, hear and sense what’s coming. |

We also use mock-ups as a necessary and valuable part of the design-development process, largely to explore and confirm aesthetic and technical unknowns. Happily, three-dimensional printing has been a great benefit here: We now use this technology every day to bring ideas to life in a quick, economical manner.

These mock-ups help us, for example, evaluate weirs as we develop unique, custom waterfalls, giving us the ability to look at the performance of new ideas and details with a fractional investment of time and effort compared to past fabrication of prototypes.

|

References: Here’s information on some of the books and firms mentioned in this article: q William H. Whyte: To findThe Social Life of Small Urban Spaces, clickhere q Jan Gehl: To findNew City Spaces, clickhere; to visit his web site, clickhere q 8-80 Cities: To see what this urban development group is about, clickhere q Claude Cormier + Associés: To see the firm’s Web site, clickhere q Dan Euser Waterarchitecture: To see the firm’s Web site, clickhere — R.M. & S.G. |

On site, new technology is also helping us evaluate local phenomena in ways we never could before. Drones, for example, are now giving us quick ways to evaluate the performance of waterforms and accurately record the effects of wind. And the great thing is that these data can, with some effort, be folded into our WATERlab simulation algorithms for analysis of splash radius relative to particular jet heights and wind speeds.

On a team level, we also believe in sharing what we’re seeing and conduct workshops to which we invite other design-team participants. The sort of hands-on experience this gives those drives further experimentation, builds deeper enthusiasm and, most important, draws team members together around a common understanding of our design capabilities and intentions.

Encompassing interaction and collaboration at this level is an investment up front with respect to time or materials, but the downstream benefits and, again, building the all-important sense of participation, makes all of this invaluable to the way a project unfolds down the line.

Next time, we’ll quickly reset the stage then move through three case studies that illustrate some of the ways multi-level engagement and participation are adding value and desirability o urban spaces and their waterfeatures.

Robert Mikula is director of special projects at Crystal Fountains, an international water feature specialist based in Toronto, Ontario, Canada. He has more than 20 years’ experience in design and project management and is also a registered landscape architect who spent several years designing aquatic theme parks before taking his current post. Mikula is also active on the education front as a guest lecturer in the landscape architecture programs at both the University of Guelph and the University of Toronto and as a frequent participant in seminar programs at trade shows and symposia. He has also written numerous magazine articles on water effects, illumination and systems design. Simon Gardiner is director of creative design for Crystal Fountains. An industrial design graduate of the Ontario College of Art & Design, he has 20 years’ experience in the watershape design and project management. He is also the author of “Design Considerations of Water Features,” an accredited online course offered by AECDaily.com, an online learning center. Since joining Crystal Fountains in 1998, Gardiner has been involved in some of the company’s most challenging projects in North America and beyond. For more information, visit www.crystalfountains.com.