A Million Blue Marbles

As part of Wallace “J” Nichols Year of Blue Mind, he recently offered a reading from his seminal book of the same name. Here is Chapter 9: A Million Blue Marbles, a treatise that broadens perspectives by focusing on something simple and small.

By Dr. Wallace J Nichols

The real voyage of discovery consists not so much in seeking new territory, but possibly in having new sets of eyes.

— MARCEL PROUST

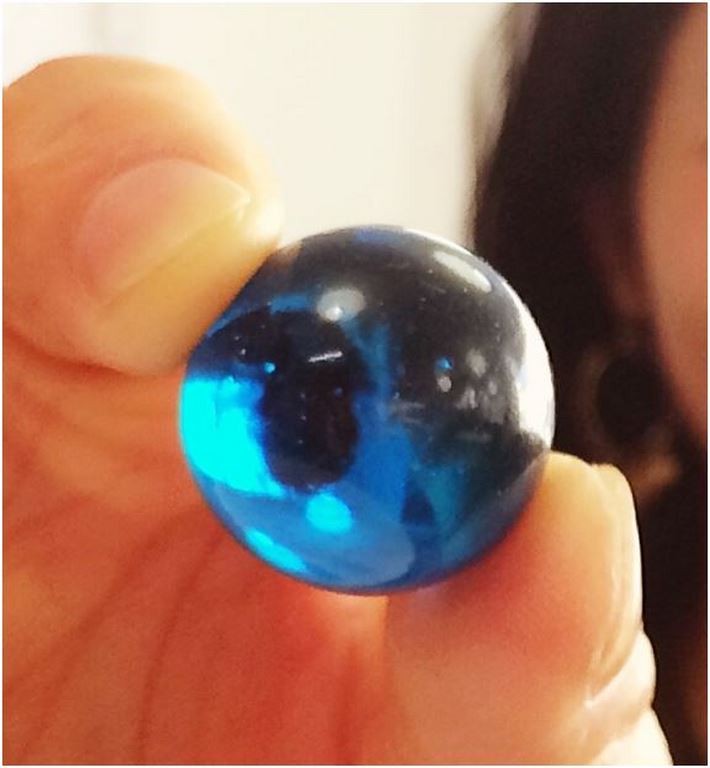

As an ocean advocate and educator, I have been telling stories about water all my life, but I’m proudest of one particular story that has been passed from hand to hand around the world. It begins with a small, round piece of blue glass . . .

In 2009, almost thirty-seven years after the “Blue Marble” photo taken by the Apollo 17 crew, I stood outside the Simons IMAX Theatre at Boston’s New England Aquarium, handing blue glass marbles to each person coming in to hear my talk.

People asked, “What’s this for?”

“Hang on to it,” I told them. “You’ll find out.”

In truth, I wasn’t sure what I was going to do. I’d handed a blue marble to a friend, LeBaron, at a cafe in Santa Cruz the week before and asked her how it made her feel. “Good,” she said. “I like it.” The image of the blue marble had been percolating through my brain ever since.

As I went through my presentation, the idea humming along in the background (and I’m sure the blue of the marble helping my creative impulse), things got clearer. Then I came to the final slide in my deck—that famous Blue Marble photo—and I knew.

Pull out the marble you received when you came in, I told the audience. Hold it out at arm’s length in front of you, and look at it. That’s what Earth looks like from a million miles away: a small, blue, fragile, watery dot. Bring the marble close to your eye, and look at the light through it. Suddenly it’s as if you’re beneath the water. If that marble actually were made of seawater, it would contain trace amounts of virtually every element. It would hold hundreds of millions of organisms— plankton, larvae, single-celled creatures — in that one spoonful.

Now, I said, think of someone you’re grateful for. Perhaps someone who loves the water, or is helping keep the planet’s waters clean and safe and healthy. Or just someone you are grateful to have in your life. When was the last time you told them that you appreciate them, if ever? Think of how good it would feel to you and to them if you randomly gave them this marble as a way of saying thank you. It’s such a simple thing that we’re taught by our parents, to say please and thank you, but we don’t do it often enough.

Take this marble with you, I continued, and, when you get the chance, give it to that person you thought of. Tell them the story of what this marble represents—both our blue planet and your gratitude. Ask them to pass the marble along to someone else. It’s a reminder to us all to be grateful, for each other and for our beautiful world.

Will you do that? I asked.

They did. Over the next few days, I received a number of e-mails and comments from audience members, and I realized those weren’t the last blue marbles I’d be sharing. I started doing the same exercise at other talks and presentations. I shared blue marbles with kids and adults. With no real budget but with the help of friends, I set up an organization and a website where people could get their own blue marbles for sharing.

The number of blue marbles passing from person to person around the world—and the stories—grew exponentially, reminding people of what they’re thankful for and encouraging them to say thanks. The Blue Marble Project went viral: within eighteen months nearly a million people had received or given marbles to express gratitude for work that benefits our planet. James Cameron took a blue marble on his dive to the deepest part of the ocean.

Blue marbles have made it into the hands of Jane Goodall, Harrison Ford, Edward O. Wilson, the Dalai Lama, Jean-Michel Cousteau, Susan Sarandon, the CEO of British Petroleum, Leonardo DiCaprio’s mom, and four-time Iditarod champion Lance Mackey, who carried one during the 2011 race. One young man who received a blue marble during a beach cleanup in Central California was inspired to turn his bar mitzvah into an “Ocean Mitzvah” at which he shared blue marbles with all the attendees.

A woman wrote that she had passed her marble on to her sister, who, rain or shine, had gone out every four weeks for twelve years to walk the beach at Pescadero, California, and record the health of that particular stretch of coastline. The marble helped the siblings have “a connecting moment”: “We talk about everything but very seldom take a moment to really say ‘Thanks for being a significant and positive influence on my little blue planet,’” she wrote.

One day in 2010, Andi Wong, technology instructor at the Rooftop School in San Francisco, called me after seeing a presentation to propose something. At the time, the kids in her school were enthralled by an educational video game called Marble Blast. Could we introduce the Blue Marble Project to the school as a real-life version of the game?

The school then created a curriculum that combined art, geography, biology, and ecology. Each child received a blue marble and was asked to pass it along to someone special. The class did research, and the kids picked people all over the world to whom they wanted to send marbles. They made boxes out of recycled maps, enclosed the marble and a note explaining the project, and sent the packages off.

It became an amazing project, as recipients got in touch with the class, sent photos of themselves with their blue marbles, and talked about who they planned to pass their marbles on to next. Marbles went to Paris, Berlin, Rome, the Sahara, New Zealand, Bolivia. A choral teacher took one to Cuba; a jazz musician took one to Tokyo. People photographed themselves and their marbles at the Monterey Bay Aquarium, on top of the Empire State Building, at the World Series. Marbles were given to kindergartners in China, to Hugh Jackman in San Francisco, and countless places between. It reminded the children how people and places are connected around the world, and how gratitude can make the world feel closer.

People ask me, “What do I have to do? What are the rules of the Blue Marble game?” The first rule is that the marble is blue. It doesn’t matter where it comes from: some have been scavenged from childhood games, antiques shops, toy and craft stores. (You can also get marbles from our website, www. bluemarbles.org.) The second rule is that you pass along the marble and thank the person you give it to, for what they do. The third is just a suggestion: that you share the Blue Marble story you created when you shared your marble, in any way that feels right — social media, poetry, song, a photograph, or best of all, spoken word.

That’s it. It’s a fun, simple, and surprisingly moving experience based upon face-to-face gratitude. Whereas fines, policies, laws, monitoring, and research are part of the hard toolbox, blue marbles provide a complementary soft power to the movement to restore and protect our oceans and waterways.

When you get one, you’ll understand. Then you have to give it away.

I have given away hundreds, thousands even (I always have two or three in my pockets, a tangible reminder with every step I take of water and gratitude), and it’s always an interesting moment when you hand a marble to someone. For those receiving a marble, it can be unexpected, even uncomfortable.

I’ve seen some people just look at it and say, “What the heck is this?” It can be a few moments before recipients really understand what the marble represents. But when they do, you can see that the gift stirs up something inside. And you can see them start to think of who they might like to give the marble to next.

I once presented blue marbles to people gathered for the International Association of Business Communicators, a group populated by vice presidents of strategic communication for a who’s who list of Fortune 500 companies. If ever there was an audience of professionals with the potential for cynicism, I thought, this was it. At the end of my keynote address I asked attendees to hold up their blue marbles, and I explained why I had shared them. I suggested that they hold their marbles to their foreheads as they imagined the people they wanted to share them with (quite a sight from the podium, I assure you).

Then I asked them to hold their marbles to their hearts as they saw themselves passing along their marbles, imagining how this would make the recipient feel at that moment. There was a palpable but silent buzz in the room, and then something unexpected happened: a good number of those business-suited men and women began to tear up. We need to remember that we all deeply love our homes and each other—and when we take a moment to consider how very much we do, it can stir us at our core.

More recently I gave a marble to Dave Gomez, who served seventeen years of a life sentence for car theft until he was freed by a challenge to California’s “three strikes” law. He looked at the marble in a way I’d never seen anyone do. “Free — that’s what it feels to look at this marble,” he told me.

What is it about a blue marble that can have such an effect? We know that, according to neuroscience, people like them because they’re blue, and they’re three-dimensional: they have weight (but not too much), temperature, texture (but not rough), mass, and we like pleasing, tangible objects. But a blue marble is really just a small piece of recycled glass, made of sand and a little cobalt to turn it blue. It costs a few pennies to manufacture. It’s common, humble, plain, insignificant.

And yet, when you look someone in the eyes and give them a blue marble with gratitude and intention, it can be the most important item in the world. Gratitude is a very powerful emotion: it opens people up, gets oxytocin flowing, and connects people to each other.

Each blue marble reminds us that we are connected to each other, emotionally and biologically. It symbolizes the deep connection between people and this planet that astronaut Eugene Cernan described as “the most beautiful star in the heavens—the most beautiful because it’s the one we understand and we know, it’s home, it’s people, family, love, life— and besides that it is beautiful.”

Looking at that small blue marble at the end of an outstretched arm invites a shift in perspective: we sometimes forget that from a million miles away we look so small and insignificant. Carl Sagan wrote of the Earth he described as a “pale blue dot” seen from a million miles away: “That’s home. That’s us. On it everyone you love, everyone you know, everyone you ever heard of, every human being who ever was, lived out their lives. . . .

There is perhaps no better demonstration of the folly of human conceits than this distant image of our tiny world. To me, it underscores our responsibility to deal more kindly with one another and to preserve and cherish the pale blue dot, the only home we’ve ever known.”

Each blue marble tells us that everything we do on this planet matters. It represents clean, beautiful water that should be accessible to everyone. And not just water for drinking or growing crops: water to play in, jump in, splash in, throw at our friends; water to recreate in, to sail or surf or fish or swim or boat in; water to watch and listen to; water to go under and explore; water to love, cherish, care for, and protect.

Our planet’s waters are worth fighting for, risking everything for, and standing up for. Because being fully immersed in water, moving across or near water, really is everything you know it to be. It truly can do all that you think it can do for your body, your mind, and your relationships. Maybe that’s why this simple idea is so easily ignored or shrugged off.

In a perfect world, our waters run healthy, clean, and free. Their waves and their currents and their stillness welcome all of us to heal, play, create, and love abundantly. For many of us, until that moment of observance or submergence, we work hard and struggle to maintain our ancient, personal connection to water. This is an interdependency with the natural world that goes beyond ecosystems, biodiversity, or economic benefits. Our neurons and water need each other to live.