The Muddy Legend of Lake Dolores

Long before waterparks became recreational fixtures the world over, a lonely desert playground in southern California — built on a system of muddy ponds — revealed both the possibility, and liability, of high-octane water thrill rides.

By Eric Herman

Just about halfway between Los Angeles and Las Vegas, along a desolate stretch of Interstate 15, motorists can still see the eerie ruins of a little-known place some believe was among the earliest precursors to modern waterparks — a crude desert “oasis” once known as Lake Dolores.

I spent many a lost weekend at this unusual and ultimately forlorn location in the late 70s and early 80s. It was a place given to wanton debauchery, lawlessness and physical hazards. It was also inexpensive and big-time fun. In the summer swelter –often well into triple digits — dehydration, misadventure and injuries of varying severity were typically the order of the day.

As rough as Lake Dolores may have been, it did portend a new type of aquatic experience that would eventually lead to far more civilized and well-engineered water theme parks (including Orlando’s Wet-n-Wild, widely credited as the first true modern waterpark).

For its part, Lake Dolores was both innovative and haphazard in the extreme. Riddled with problems and mired in local folklore, the fact that it no longer exists beyond its haunting remains is somehow fitting.

ROADSIDE ATTRACTIONS

Original owner John Byers first opened the property, named after his wife, in 1962 in the rural desert community of Newberry Springs. Taking advantage of the area’s readily accessible aquifer, Byers first envisioned Lake Dolores as a watering hole for off-road motorcyclists and tourists traveling between L.A. and Vegas. His idea worked and for the next two decades, he expanded the property into its infamous high-octane incarnation.

The “lake” itself was actually a 273-acre spring-fed system of interconnected manmade ponds and channels, most only a few feet deep. Even though the water was cloudy and pond bottoms muddy, in the blistering heat it was refreshing.

The spoils from excavating the lake were used to create a massive manmade ridge-lined hill that rose approximately 90 feet over the otherwise flat and arid terrain.

Accessed by railroad-tie steps, one side of the hill was devoted to eight, side-by-side, 150-foot long, aluminum Speed Slides. Riders plummeted head first down an exhilarating 60-degree slope on small inflatables over thin sheets of water. The slides flattened out at the bottom sending riders skidding at a thrilling pace across a narrow channel for 50 yards or more. High-speed wipe outs and side-swipe collisions were common, and often intentional.

Adjacent to the speed slides were two primitive zip lines descending from the summit at a steep angle, where riders would let go and crash into the water where it was sufficiently deep enough for a safe splash down. The challenge was to be sure to hold on long enough to reach the water, because for the first 100 feet the lines traveled high over the gravelly slope of the hill. If you let go too soon, as some did from time to time, the impact was painful and abrasive. Holding on too long would result in overshooting the water and possibly landing on spectators along the shore.

On the other end of the hill rose the park’s recreational centerpiece; a pair of features so dangerous and terrifying that no version of their species exists in modern waterpark rides today — the infamous Stand-Up Slides.

As the name suggests, these were waterslides rode in a standing position. The design consisted of wedge-shaped aluminum troughs with flat bottoms upon which riders attempted to remain upright, while gliding on a thin stream of sheeting water. The concept was flawed in that it assumed a level of user agility that many, if not most people do not possess.

As a result, a majority of riders wound up sitting by the end of the slide, but those who managed to stay on two feet could reach impressive speeds before being shot off the end, at a height of 15 feet with a slight downward angle. Because there was no one monitoring the intervals between riders, the risk of landing upon fellow thrill seekers was part of the ride’s thrill and dangerous mystique.

As a side note: the rails of the slides would become superheated in the blazing desert temperatures, adding minor burns to the exhilarating experience.

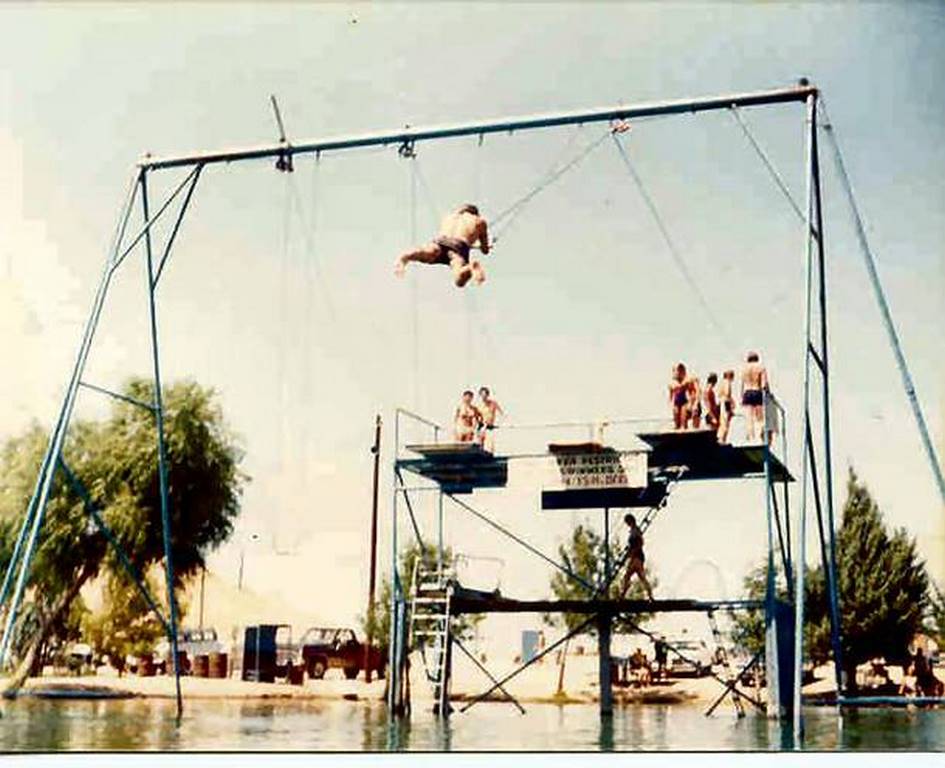

Adding yet further misadventure on an even more vertical axis, a 20-foot trapeze platform and swing rose from the center of an adjacent pond strategically located by the park’s only concession stand. The swings were particularly hazardous as the inertia and centrifugal force generated by the downward trajectory made it extremely difficult to maintain your grip when reaching the arc’s nadir, something you don’t ever consider when watching trapeze artists at the circus. It requires considerable strength. For many at Lake Dolores, that realization became manifest in a high-velocity face plant.

AT RISK

To their credit, the Byers soldiered on and were constantly expanding and upgrading the attractions, including a lazy river, bumper boats, go-cart track, a restaurant and an arcade. They also employed more lifeguards and security personnel. For a time, Lake Dolores became far more family friendly.

Eventually, however, legal and financial trouble caught up with the property. Lake Dolores withered and closed unceremoniously sometime in the late ’80s. It’s demise passed with no public notice and not even those of who enjoyed so many experiences there cared at all. Modern waterparks had sprung up everywhere, and there was little reason to make the long trip to the middle of the barren desert to ride waterslides.

In 1990, a group of investors purchased the property, tore out the old features and installed modern waterpark rides, a restaurant and an arcade. It reopened in 1998 under the name “Rock-A-Hoola” but only lasted a short time as owners closed the park and filed for bankruptcy in 2000.

Yet another group of investors tried again, reopening the park in 2002 as “Discovery Waterpark.” It operated only intermittently and again closed in 2004, once and for all leaving its structures and attractions for scrap and ruin.

Today, the ghostly remains stand as a fitting homage to a muddy legend and a by-gone age of loose restriction, physical peril and a brand of carefree fun.

ON A PERSONAL NOTE

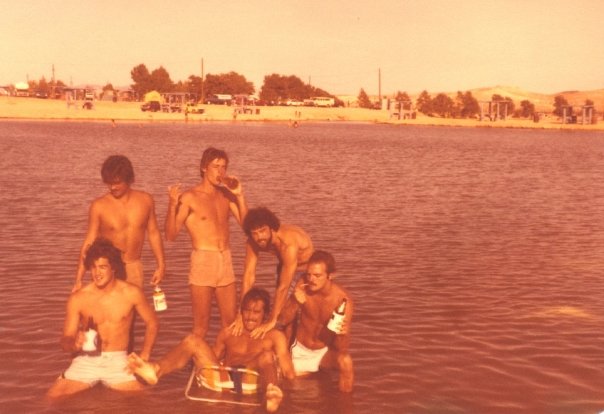

That’s the public-facing story. As part of my own experience, Lake Dolores is a strangely significant place. I started going there with groups of friends from Neff High School in La Mirada, during the summer in the late 70s. It took about two hours to get there and cost $15 a day to camp and use the rides. We set up tents and canopies, brought our own supplies, and slept under the stars. Music, laughter and the sounds of various shenanigans could be heard at all hours.

Those trips continued into my college years with many of my brothers from Sigma Pi fraternity at Cal State Fullerton. The gentleman in the opening picture is one of those fellow fun-seekers, Steve Guerena, wisely sitting down on the Stand-up Slide. The image was taken by our mutual lifelong friend, Rob Norden. I could rattle off a list of at least 30-plus names of those I camped with on the spartan desert banks.

The place was a perfect fit for the freewheeling fun we were seeking at the time, and there are many fabled stories that have circulated over the years. In all, I was there probably more than a dozen times, a ritual that continued into my mid-20s.

As is true of so many experiences, it’s not really the place or the activity, but the time spent with fellow humans. I’m still close friends with a number of fellow frolickers from those days, and I’m proud that we have in our own ways lived rich and fulfilling lives. We still sometimes look back and laugh at those rough and tumble times at Lake Dolores, and countless other places, all the richer and wiser for the experiences we shared, and survived.

Editors Note: An earlier version of this article appeared in AQUA Magazine in June 2014.

Opening photo, sitting down on the Stand-Up Slide, circa. 1982, Rob Norden. Second photo, Lake Dolores today, the Society of Forlorn Places. Lower photo, the trapeze in action, Las Vegas Weekly.