The Frothy History of pH

For anyone working with water chemistry, the pH scale is key to understanding a range of factors, from mineral saturation to the effectiveness of chlorine. It is essential to understanding water as the so-called “universal solvent” and the management of watershapes of all types. What many may not realize, however, is that this all-important chemical convention resulted from experimentation with beer.

By Lauren Stack

Soren Peter Lauritz Sorensen was a famous Danish chemist who invented the pH scale in 1909. His invention remains critical to this day in many aspects of daily life, including the sanitation of water.

Born to a farming family on January 9, 1868, in a tiny town near the coast, Sorensen studied science and started his early career consulting for the Danish navy. He earned his doctorate for research on cobalt oxalates — complex inorganic structures that have broad applications in nanotechnology science.

At the time of his discovery, Sorenson was working at the legendary Carlsberg Laboratory in Copenhagen, where he was appointed head of chemistry at age 33. Studying fermentation, he was working to figure out ways to brew the best tasting beer of the highest quality. (This was not surprising given that the brewing company of the same name first established the lab.) The lab had already developed the famous Kjeldahl Method, a technique that in use today for measuring nitrogen content in foods and beverages.

Sorenson was specifically studying the formation of amino acids and enzymes made from proteins – which home-brew enthusiasts and Brew Masters know are critical to the fermentation process. Sorensen realized that hydrogen ion concentrations were key to how some enzymes do their work. To keep track of hydrogen ion concentrations, he developed the pH scale, which has use in chemistry of many types ever since.

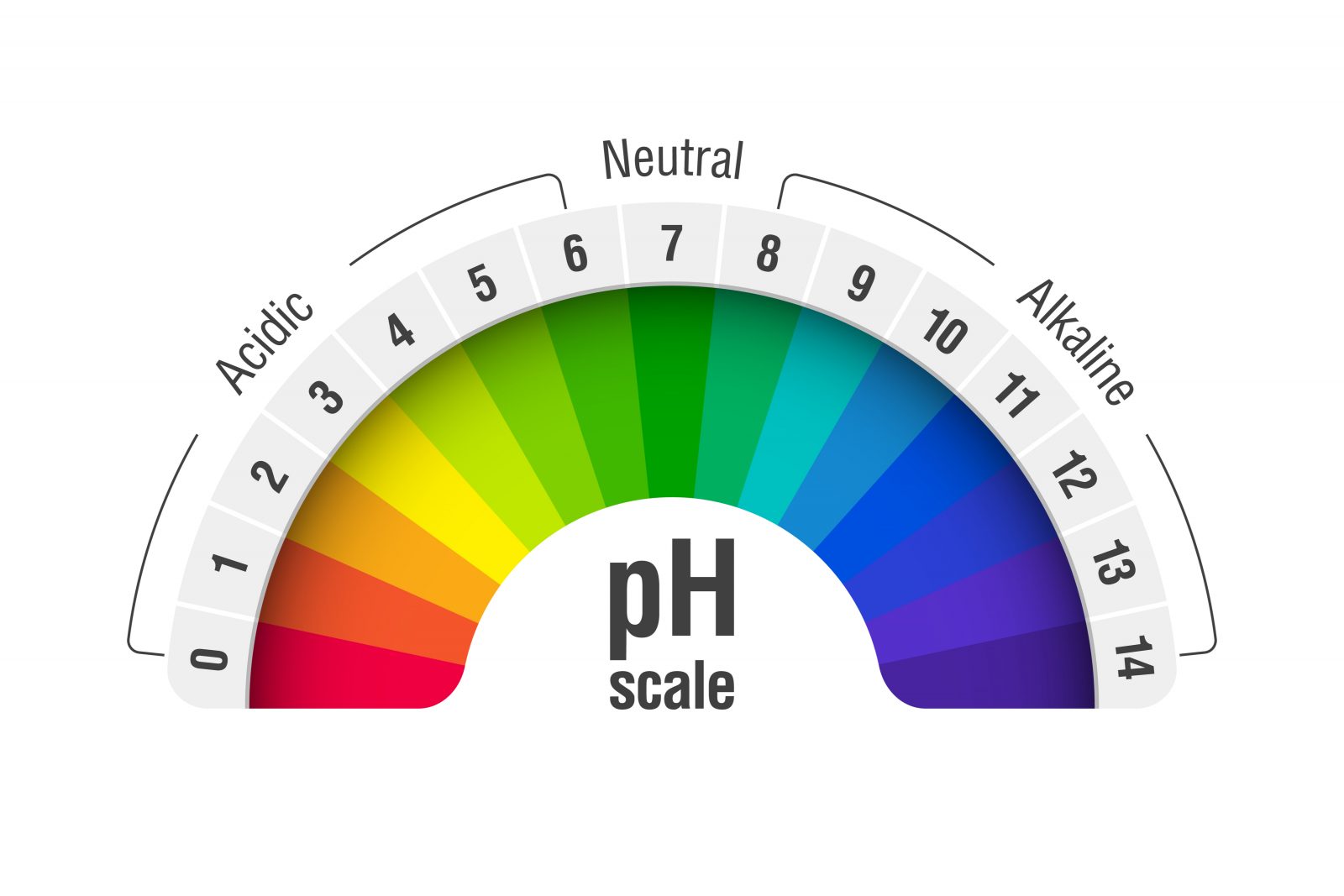

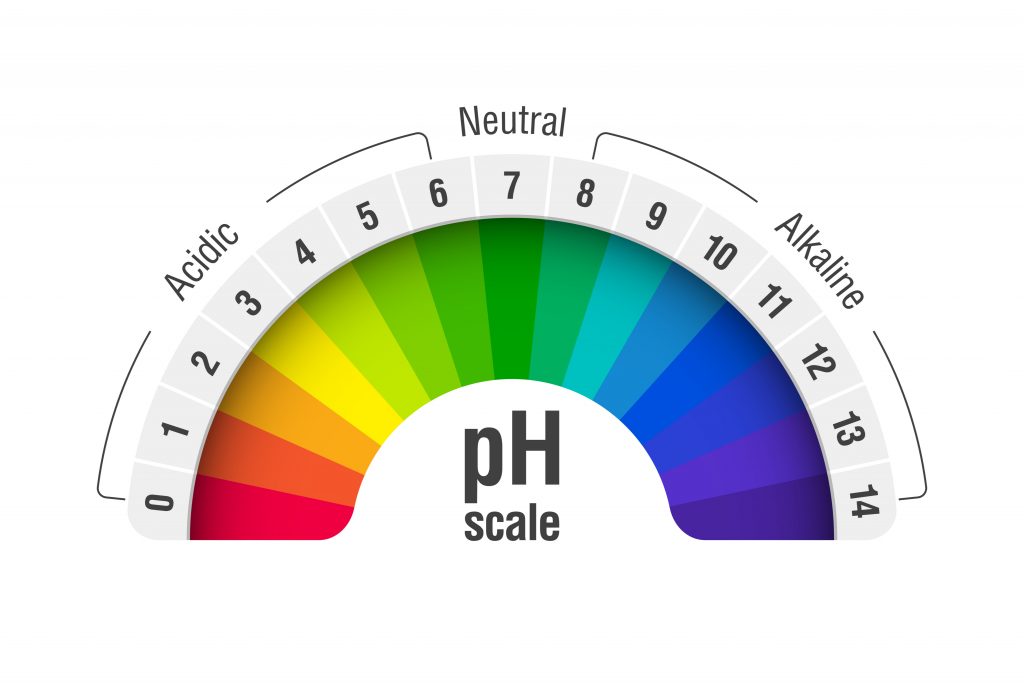

The term pH means “potential of hydrogen,” or the “power of hydrogen.” It is a numeric scale – with a range of 0 to 14 – used to specify the acidity or basicity of an aqueous solution. Until Sorensen introduced the pH scale, acidity or basicity was determined using a device known as a galvanometer, an overly complex and delicate instrument for measuring small electric currents. He sought a simpler way to assess hydrogen concentration.

The pH scale is logarithmic and inversely indicates the concentration of hydrogen ions in the solution. That means the higher the concentration, the more acidic the solution and the lower the pH.

The concentration of hydrogen ions in a liquid can vary drastically which is why Sorenson used a logarithmic scale, where each unit changes by a factor of 10. Keeping in mind that the scale is negative, a solution with a pH of 4 is ten times more acidic than one with a pH of 5 and one hundred times more acidic than a pH of 6.

Measuring pH is essential to the management of water in pools and spas, as well as in public utilities. Other uses include designing batteries, diagnosing blood disorders, and — in the age of climate change — measuring the acidity of the ocean, among countless other applications.

Sorensen found that enzymes that hasten biochemical reactions work well in certain pH environments and poorly in others. For instance, pepsin — an ingredient of gastric juice — loves acid; but, lipase — found in the pancreas — requires alkalinity. Human blood normally falls within a narrow range of pH 7.35 to 7.45, near the scale’s neutral midpoint of 7.

Aberrant pH levels of bodily fluids can signify health problems and can help diagnose metabolic and respiratory problems. Higher blood pH values, indicating alkalosis, can signal hyperventilation, dehydration, or liver failure, among other problems. Lower blood pH, indicating acidosis, points to pulmonary malfunctions, kidney failure or an inability to excrete acids.

Sorenson’s accomplishments earned him memberships in scientific societies around the world, and his colleagues remembered him as a genial educator. “He was kindly, courteous, ever-willing to listen to those who had not his fund of knowledge and always ready and glad to impart something from his vast store of learning,” wrote A.J. Curtin Cosbie in the journal Nature in an obituary for Sorensen, who passed away at the age of 71 in 1939.

Cosbie also wrote, “Sorensen’s classic work on hydrogen ion concentration will remain as a permanent monument among those who know little of his other work.”

So, the next time you test and/or adjust pH in a watershape, remember that the system you are using was developed long ago in the pursuit of the perfect brew.

Lauren Stack is current Vice President of Operations for Watershape University. She has a bachelor’s degree in Chemistry from the University of Pittsburgh, graduating summa cum laude.

Source: Science History Institute and vox.com.

Graphic by Alhovik | Shutterstock