The Architect Connection

Those of us in the design and construction industry are engaged in a singularly complicated human endeavor. To make things work, it’s common for many technical disciplines to come together, including soils and structural engineers and contractors and subcontractors as well as architects, interior designers, landscape architects, lighting designers and watershapers – all working in concert to bring form to the goals and aspirations of the clients.

These professionals unite in designing spaces that people use and occupy – a simple yet profound thread that ties all of us engaged in any given project together. Through our combined efforts, we change and influence lives by virtue of the ways we conceive, organize and realize these spaces.

When we truly succeed, it is because we have been able to integrate everything – the needs of the client, the natural and artificial constraints of the project and our individual creative visions – in ways that become an inspiring physical reality our clients and those who visit them will experience on a daily basis for years to come.

That’s a lofty vision, and I believe it happens only when all participants in the process understand one another and can communicate about a design solution that coalesces in service to a client. It’s an exercise that takes effort and dedication; unfortunately, it’s also one that relatively few in the building business see as necessary or as benefiting the bottom line.

In this article, my aim is to help change that unhappy situation and start building bridges that will help more of us understand and respect each others’ missions and goals. Personally, even if this understanding didn’t add to the bottom line (which it most definitely does), I’d still compose these articles simply because I would rather spend my time and energy working in cooperative environments rather than doing battle with misperceptions that too often lead to results that aren’t everything they should be.

SETTING A STAGE

These days, at a time when watershapes are commonly being integrated into the designs of buildings of many types and sizes, it serves our interests as architects who incorporate water into our thinking to make certain watershapers – that is, those who’ve chosen water as an artistic medium – know what we do, the processes we employ, the language and terminology we use, our project goals and, most important, our interest in fostering positive working relationships with watershapers.

Of course, just wanting such a discussion doesn’t make it particularly easy, mainly because there are as many approaches to projects as there are individual architects and ways of practicing the profession. Just as in watershaping, some of us specialize in commercial work, others in residential projects; some generalize across styles, others focus on certain genres; and some work in huge companies with stratified layers of responsibility while others are sole practitioners.

For all that functional diversity, there are certain commonalities shared by all architects, and what I want to do here is communicate with you about that common ground by way of helping you work with any of us on any given project.

If the objective is building a hospital, for example, and your task as a watershaper is to design and install a fountain, your contact will likely be an architect who is part of a large firm. It is also likely that many other people within the firm will be involved, in which case the person with whom you are mainly working may have to answer to higher ups when it comes to issues of design intent, scheduling and budget.

On another project, by contrast, you may be dealing with homeowners who have hired an individual architect to whom they have entrusted all design considerations related to a single property. In some cases, the budgets are modest; in others, they may be huge beyond belief. Either way, the one-on-one shape of the working relationship is likely to be more direct and less cumbersome – depending, of course, upon how well the two professionals communicate.

Considered separately, the general scenarios outlined above define the need for two distinct approaches not just for the architect, but also for the watershaper. This simple recognition is a good starting place: Understanding the fact that each professional brings preconceptions to the process and that those preconceptions need to be tempered by the project at hand is essential if the project is to become the team exercise it should be.

PROFESSIONAL NATURE

In addition to project type and scale, personalities are also factors in establishing relationships and often express themselves in less-than-predictable ways. Understanding the character of architects and the way they see their profession is the key – and can make your work as a watershaper more effective on site and more enjoyable all around.

Architects, as with other professionals, consider their work to be an extension of themselves; in doing so, they can seem set in their ways and unwilling to bend, but the simple truth is that prejudging them based on stereotypes is as hazardous here as it is in any other pursuit.

Architects indeed come in many shapes and sizes – as any of you who’ve worked with more than a few will know. Each approaches a project in his or her own unique way, and it’s no accident that people say if you put three architects in a room and present then with a design challenge, you’ll get at least five different solutions. The reason for this diversity of their responses is simple: Each project involves many elements, and solutions will vary depending on the way the design team looks at the possibilities.

| As an architect, I envisioned the complex set of watershapes seen here, but all the actual planning and work involved in specifying and building these elaborate water-in-transit systems, ‘floating’ concrete pads, fire effects, lighting schemes and subtle finishes are details I must turn over to others on the project team. The only way to make everything work together visually and functionally is for everyone to engage in open, clear communication across disciplinary lines from start to finish. (Photos by Allen Karrasco, Oceanside, Calif.) |

In all we do, however, we ultimately work with that simple principle mentioned at the outset of this article: No matter whether it’s a hospital or a one-room addition to a single-family home, our job as architects is to create space for human activity. It’s a conceptual exercise in which our aim is to assemble components in such a way that we create symphonies in which the whole is greater than the sum of the parts.

But that’s enough of the philosophical background: What this bridge-building is really all about is language, terminology and the basics of communication as they relate to architecture, architects and those who interact with them.

Look at it this way: Architects are in the business of designing spaces to meet a need, satisfy a stated program and build an environment that serves a client while giving expression to an artistic mindset. This is why, in the design process, architects seek to explain what they’re after in ways that give a project its form. The “language” they use is at times a set of drawings, but on other occasions it involves models or words – tools they have revised and refined over time to communicate their ideas about built environments.

WALKING THE TALK

The language we’re discussing constitutes the common ground on which watershapers and architects should meet – but often don’t.

That’s ironic because, although the media we use and the settings in which we use them may be different, the processes we pursue with our clients are much the same. Once we leave the world of modular or cookie-cutter solutions behind, we enter a custom realm in which small things have major effects and project success depends on our ability to communicate about ideas and processes without getting bogged down by language barriers.

Architects approach their clients in ways that help those clients achieve their perceived project goals. This approach will vary between residential and commercial projects and from restrained to flamboyant owners. For their parts, clients hire architects because they like what they’ve seen. By extension, architects are like jazz musicians in that they play to the room and need everyone else on the design team to pick up and play the same tune.

In these cases, the client places trust in the architect; in turn, the architect finds other professionals with whom to entrust key portions of the project. Not to beat the musical analogy too hard, but much of a project’s cadence and style are determined by the relationship built between architect and client.

As an example, in my practice I aim to set things up in such a way that design flows seamlessly into construction. I do so because I know my clients have hired me to make certain everyone on the design/build team works together to create a unified, integrated outcome. To succeed and make the process enjoyable, everyone involved must approach the project as a unified team.

In guiding that team, I am fully aware that others have knowledge I don’t have – and that I have knowledge they might lack. How much one or another of us knows is beside the point: What’s important is using our knowledge appropriately to produce the best possible results.

What I’m discussing here should be familiar enough: As custom watershapers, you know that your projects work best when everyone involved, from the excavation crew to the finish applicators, lines up and approaches the project with similar attitudes and ambitions. Just as you find opportunities and constraints and discover ways to meet clients’ goals, we architects define directions, set broad frameworks and rely on team members to understand where we’re headed and how programs can best be implemented.

THE HEART OF THE MATTER

On that level, it’s all about communication. In cases where you’re working with someone for the first time, the importance of establishing open lines of communication is both obvious and essential if you are to achieve an outcome that pleases the client.

In other words, successful projects are no accident. Success happens when design and construction professionals infuse far more into a project than could ever be captured or conveyed by a set of drawings and specifications. It happens when we also recognize that our work as architects, landscape architects and watershapers (and anyone else who gets involved) is incomplete and ineffectual unless it is integrated with the work of everyone else who’s involved.

A lack of communication is at the root of most failures because it leads to lapses in teamwork and undermines everything that supports team performance. And the great difficulty is simply this: Once things go wrong, it’s very difficult to adjust them in ways that make them right again because the tasks at hand are so complex.

And things are only getting more complex these days as we continually push the envelope of possibilities with new materials, new technologies, new techniques and new expertise. This is why it’s so difficult to go solo these days: There are too many fields to master, and the best of us often need help in carrying off programs to the greatest possible result.

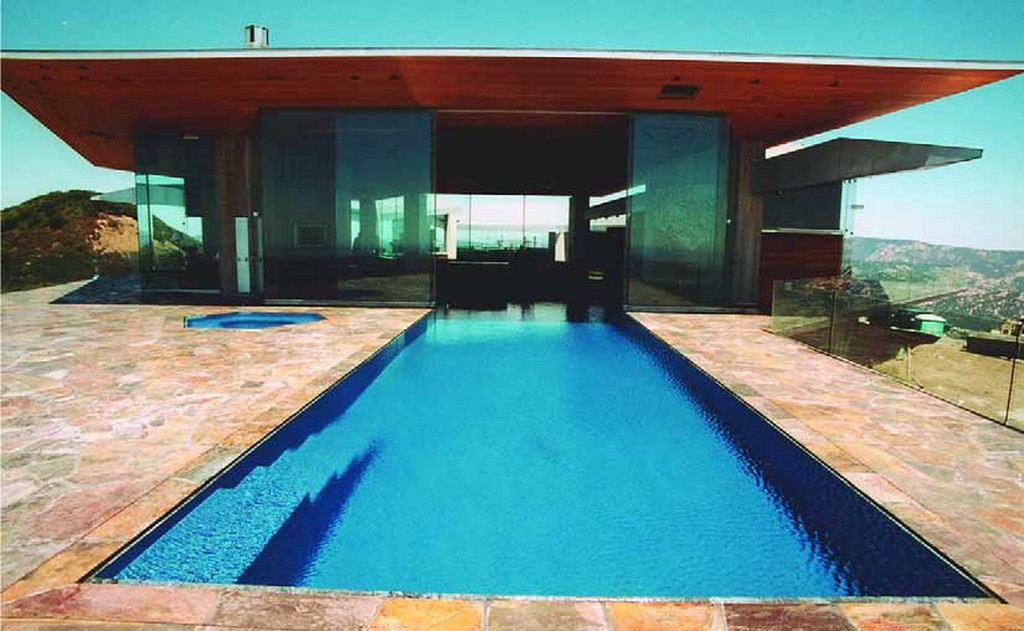

| This project – designed by Helena Arahuete of Lautner Associates (Hollywood, Calif.) and executed by Steve Dallons of Pacific Pools (Alamo, Calif.) with the assistance of a broad range of consultants of every conceivable sort – is a classic example of what can happen when everyone on a design/build team buys into a singular vision. In this case, in fact, it’s safe to assume none of this would have been possible without amazing levels of communication and collaboration. (Photos by Steve Dallons, Pacific Pools, Alamo, Calif.) |

We are, in other words, all operating in an environment in which we are frequently called upon to participate as members of a team. Doing so requires each of us to use our communication skills to convey our intentions to the rest of the team and at times correct the paths being taken by other team members. It also calls on us to respond and adjust the plan as challenges arise.

When architects are involved in a project, they typically take a central role in identifying what we call a project’s Program Requirements. This encompasses a clear delineation and evaluation of the site, any relevant regulatory constraints, any client preconceptions or desires – and a declaration of how an overall design will overcome obstacles and meet objectives.

On that level, it’s up to architects to understand the framework within which every other team member operates. Also important these days, it’s necessary for team members to be responsive not only to the team leader but also to know how their work relates to other team members wherever operational intersections occur.

UNITED FRONTS

In the most practical of ways, what all of this points to is the fact that traditional boundaries between building professions (and professionals) are being eroded by all of this team activity involving architects, landscape architects, watershapers and others. This functional integration affects everything from project scheduling and on-site management to distilling and producing the essence of the design itself.

On that level, none of us can operate in isolation in endeavors marked increasingly by innovation, specialization and integration. We each exist in realms in which technological innovations alone are occurring faster than we can process. This leads in turn to specialization in design and construction fields, which in turn leads to a supreme need to integrate activities and encompass not only traditional design fields but also new ones.

More than ever before, in fact, integration is the key word in the design/build process. On your part as watershapers and on mine as an architect, we both need a working knowledge of all these other design disciplines and their vocabularies in order to plan and execute effectively.

And it’s even more complicated these days by the desire of clients almost everywhere to have exteriors flow as extensions of interior spaces. The only way this can happen is with integration and the open communication it requires across various disciplinary lines.

In other words, none of us really operates in isolation these days. If one starts with the architecture of a home as an example, the interior must be integrated with exterior spaces – and this will only happen if the project is conceived as a unified whole. Yes, each discipline still pursues specialized functions, but the program requirements influence every element of the project, forcing all of us to communicate and interact.

This requires not only clear paths of communication, but also something of a chain of command. Situations in which, for example, a subcontractor works out a solution with the owner without consulting either the general contractor or the designer of that particular detail are recipes for disaster – not because the solution is necessarily bad, but because the implications of that small decision may affect the overall design in ways that must be understood.

And when those decisions have to do with a watershape, the inherent complexity of the structure typically amplifies the seriousness of each independent move.

BOILED DOWN

On a recent project, my design called for a building to be placed immediately adjacent to an existing pool that was undergoing a thorough remodeling, including relocation of the equipment. This sort of construction can get quite complex, but we made it work with relative ease because we saw the need up front to communicate on everything – and the result was a success, both for the client as well as for the building team.

In order to make these relationships function at their best, clients must be persuaded to form project teams as early in the process as possible.

This enables me as an architect to get a clear sense of what watershapers and others bring to the table with respect to expertise, experience and their understanding of design and construction as related to a specific site. At the same time, it gives the watershaper a clearer understanding of the architect/team leader’s approach as well as cues to the needs and desires of the client and the nature of the setting under discussion.

Actually, most of what I’m proposing here about communication and teamwork should be familiar to readers of this magazine. For years, in fact, I’ve been impressed by how many contributors have written about their participation on design teams and how they’ve used those relationships to establish watershape designs that harmonize superbly with their surroundings.

You’ve heard those suggestions from the watershapers’ perspective; what I offer here is consideration of the process from the team leader’s perspective and a suggestion of the value to be found in taking inspiration from the context an architect sets in designing the primary structures on a property. Bottom line: Isolation is counterproductive in this new design world in which we find ourselves. It’s a place where, quite simply, the ways in which your efforts as a watershaper must integrate with the efforts of other experts is becoming the single greatest key to success.

Greg Danskin is principal of the firm Greg Danskin Architect in Escondido, Calif. He established his practice in 1991 and through the years has designed projects ranging from remodels and custom residential homes to retail, commercial, restaurant, healthcare and religious facilities. This diverse spread of project types has built his understanding of the interrelatedness of various disciplines in the creation of both private and public spaces. Danskin earned his degree in architecture from Montana State University in 1985 and his California license in 1989. He was a volunteer in developing the city of Escondido’s Downtown Specific Plan and has served in numerous advisory capacities for the Grape Day Park Foundation, Trinity Housing Group and the Buckheart Ranch for Boys. An Eagle scout, he is also involved in a variety of community groups and is a Cub Scout leader.