Buoyant Explorations

There may still be some who resist the idea, but by now it is verifiable fact that plant material can be used to treat and purify water in artificial watershapes as well as in natural bodies of water. For decades, in fact, scientists have borne witness to these processes in natural wetlands – so much so that today, these concepts are being studied around the world using artificial wetlands and floating islands that mimic natural structures and processes.

Our firm, Floating Island International of Shepherd, Mont., is predictably focused on the floating island concept. In our efforts to understand all of the nuances and specifics of how plants on floating islands can be used to best advantage, we have made contact and worked worldwide with scores of independent researchers and institutions across a range of settings, applications and agendas.

Yes, we’ve been gratified by the resulting findings and the benefits that reportedly flow from use of our systems. In a more important and greater context, however, we see this collection of empirical data and anecdotal evidence as conclusive proof that biological water treatment is not only viable, but is also surprisingly dynamic over a broad spectrum of situations in which contaminants are found in open bodies of water.

IDEAS AFLOAT

Floating islands (or, as they are referred to in scientific literature, “floating emergent wetlands”) are a new technology focused on biomimicry, which in our case involves the replication of certain “natural” aquatic structures using recycled materials.

Basically, what we’re doing with our technology is fostering the “wetland effect” by developing combinations of surface area and circulation within waterways that set the stage for thriving plants, burgeoning microbe colonies and naturally healthy water. (A leading researcher in this effort is Dr. Chris Tanner, a world-renowned wetland biologist with the National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research in New Zealand: He’s the one who coined the term “floating emergent wetlands.”)

Nature is the model at the core of our research, and along the way we’ve studied natural floating wetlands and islands as well as coral reefs, overhanging banks and even beaver dams. Our success in reproducing these structures artificially and making them fit in naturally bodes well, we think, for the ability of human beings to live more gracefully within and around aquatic environments.

In a broader sense, in fact, we’ve reached the point where we believe that humans can co-exist with sensitive marker species in complex urban settings, around intense agriculture and even in areas affected by stormwater runoff or where waste streams infused with toxic heavy metals flow away from mining operations.

Those are big claims, but we’ve learned that by using nature’s own wetland model and developing new substrates and island designs that concentrate or expand the wetted surface area, it may be possible (with time and careful management) to remediate even huge, hyper-eutrophic freshwater systems and bring them and their dependent species back to health.

As you will see from some of the studies reviewed below, we’re at a moment of historic transition: As watershapers, you are invited to add your creativity and aesthetic talents to this transition. An important step towards this shift will be the development of urban environments that are beautiful while simultaneously conserving and stewarding precious potable water resources.

Are these ideas ambitious? Absolutely – but in discussing them I draw support from numerous research studies, pilot programs and varied forms of experimentation, including the dozen described briefly below:

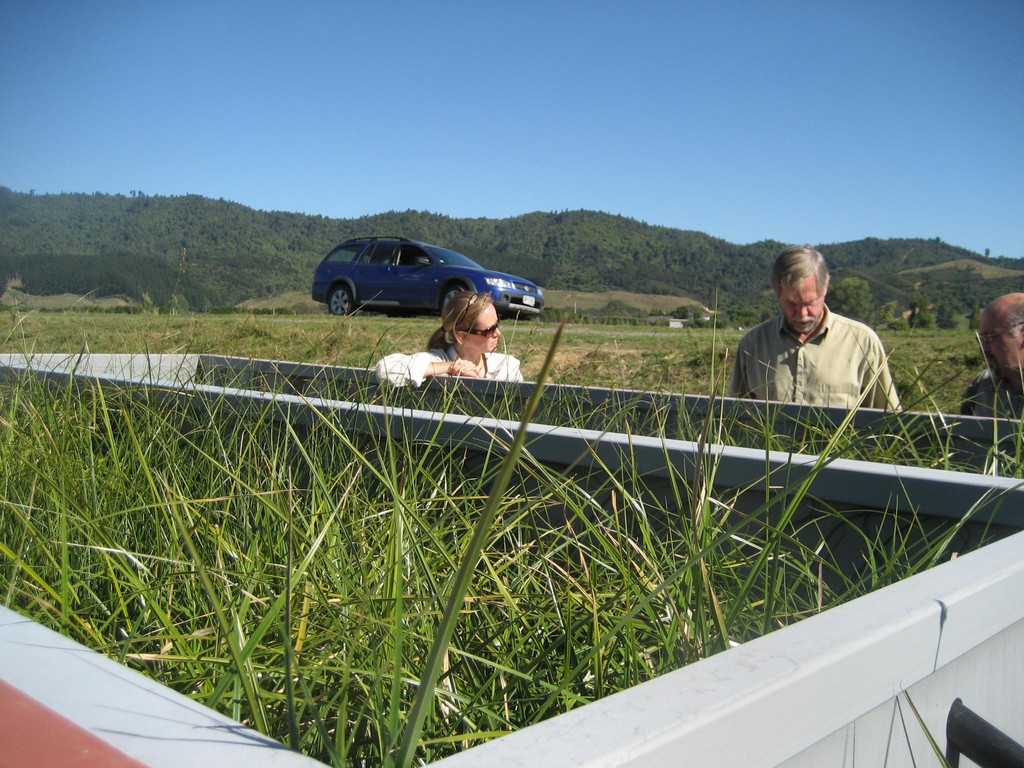

1. At the National Institute of Water & Atmospheric Research (New Zealand), Dr. Chris Tanner and others have been working with our firm’s floating wetlands concept for five years. One groundbreaking study measured significant zinc and heavy metal uptake by wetland microbes and plants living on these structures.

The objective of these investigations is defining how best to work with stormwater management ponds – a key consideration in modern urban planning and a pursuit that so far has resulted in numerous presentations and publications. Spinning off data collected to date, Dr. Tanner is currently running a study comparing the efficacy of surface flow, subsurface flow and floating emergent wetlands in reducing nutrient loads of wastewater.

The objective of these investigations is defining how best to work with stormwater management ponds – a key consideration in modern urban planning and a pursuit that so far has resulted in numerous presentations and publications. Spinning off data collected to date, Dr. Tanner is currently running a study comparing the efficacy of surface flow, subsurface flow and floating emergent wetlands in reducing nutrient loads of wastewater.

2. For the island nation of Singapore, water is an abundant but precious resource for a population that continues to grow at an accelerating pace. In the interest of conserving water to permit future growth, the government is attempting to develop a “freshwater loop” – a series of interrelated systems that focus on recycling and conservation.

2. For the island nation of Singapore, water is an abundant but precious resource for a population that continues to grow at an accelerating pace. In the interest of conserving water to permit future growth, the government is attempting to develop a “freshwater loop” – a series of interrelated systems that focus on recycling and conservation.

As part of this program, the government protects numerous reservoirs from saltwater incursion. We provided the research team with several small floating islands that have since been placed on the Sungei Punggol Reservoir, a classic example of concentrated wildlife (including six-foot-long monitor lizards) and fish surrounded by an urban setting.

3. Citizens for Conservation is a non-profit organization based in Barrington, Ill., and to describe those folks as “early adapters” would be an understatement: This eclectic mix of nature lovers, stockbrokers, retired persons and other citizens has taken on the challenge of restoring native tall-grass prairie, waterways and wildlife habitats within minutes of downtown Chicago.

3. Citizens for Conservation is a non-profit organization based in Barrington, Ill., and to describe those folks as “early adapters” would be an understatement: This eclectic mix of nature lovers, stockbrokers, retired persons and other citizens has taken on the challenge of restoring native tall-grass prairie, waterways and wildlife habitats within minutes of downtown Chicago.

In one award-winning project, the group launched 42 floating islands of various sizes into a stormwater management pond near a big subdivision. Before long, sandhill cranes had set up nests on one island, and a wide range of rare plants has taken hold on others.

4. Floating Island West of Sacramento, Calif., is currently collaborating with several environmental groups (including The Nature Conservancy) in deploying floating islands as secure habitats for coho and king salmon fingerlings within the Sacramento River delta.

The environmental groups have also been purchasing upstream spawning sites and protecting them with conservation easements. Among their missions is restoration of critical riparian edge habitats not just for salmon, but also for key insect and plant populations. Stream banks damaged by cattle, for example, are being fitted with overhanging bank structures that replicate original habitat conditions.

5. Approximately 2,100 square feet of floating island was launched in 2009 at Chicago’s Lincoln Park Zoo in an effort to reduce both the volume and the nutrient load of water flowing out of the zoo’s waterfowl exhibits.

Designed by Shaw Environmental & Infrastructure (Baton Rouge, La.) and based in part on experience gathered at Zoo Montana in Billings, Mont., the project includes solar-powered aeration and strategically positioned islands as well as perimeter netting – a classic use of floating emergent wetlands and a wonderful visual addition to the zoo’s exhibits.

Designed by Shaw Environmental & Infrastructure (Baton Rouge, La.) and based in part on experience gathered at Zoo Montana in Billings, Mont., the project includes solar-powered aeration and strategically positioned islands as well as perimeter netting – a classic use of floating emergent wetlands and a wonderful visual addition to the zoo’s exhibits.

Floating Island Environmental Solutions (also from Baton Rouge) developed the netting solution to protect the islands and also helped with plant selection and the planting scheme to ensure that all design criteria were met.

6. The GEF Program is a large-budget initiative aimed at installation of sewage-treatment systems in parts of the Caribbean basin where human and agricultural wastes have historically been flushed into the nearest waterways and, ultimately, the open ocean – a practice that has resulted in dying coral reefs and development of organic sludge deposits on beaches.

Given the obvious implications the program has for human health, tourism and the health of fisheries, the goal is to install wastewater systems as quickly and cost effectively as possible. An international team including the engineering firm of Sanderson Stewart (Billings), Ray Davis of Floating Island Southeast, environmental consultant Jeff Griffin and consulting engineer Frank Stewart are developing a system that goes well beyond simple sludge containment.

Eventually, this system will sequester nutrients using floating islands and floating emergent wetlands as cleansing “lids” over wastewater ponds – and will do so at about the same cost that would be involved in building conventional sludge ponds.

7. Off the coast of Southeastern Australia in Tasmania, Kauri Park Nursery (a floating island manufacturer based in New Zealand) has proposed development of a 317,000-square-foot archipelago to provide for cost-effective uptake of heavy metals found in the tailings stream of a local goldmine. The goal here is to treat the water before it infiltrates one of Tasmania’s premier trout streams.

If implemented, the proposal will save the mining company more than 80 million Australian dollars compared to the cost of installing a conventional metal-removing system using reverse osmosis technology. (Work on zinc and copper uptake conducted by Dr. Tanner at New Zealand’s National Institute of Water & Atmospheric Research is the basis for this ambitious concept.)

8. As project manager for American Electric Power (Columbus, Ohio), Christina Svoboda is running several studies to test the efficacy of Elevated BioSwales, a biomimetic structure developed by Floating Island International that conforms to the shape of any swale or ditch while providing a strategic wetland effect with either a seasonal or continuous flow.

In effect, the material provides a “leaky dam” effect, slowing down storm surges and providing another tool that facilitates the biosequestration of nutrients, heavy metals and other toxins. In Svoboda’s case, she’s dealing with water flowing through mine tailings – work that will be mirrored in Billings in 2010, when the Montana Public Works Department will be using Elevated BioSwales as a stormwater-management strategy in connection with development of new roads.

9. In the summer of 2008, a 2,000-square-foot floating island was launched just downstream from a fish hatchery in Calgary, Alberta, Canada. The island, designed and planted to mimic a floating fen, is being used to sequester hatchery-generated nutrients before they reach Bow River, a natural (and noteworthy) trout fishery.

9. In the summer of 2008, a 2,000-square-foot floating island was launched just downstream from a fish hatchery in Calgary, Alberta, Canada. The island, designed and planted to mimic a floating fen, is being used to sequester hatchery-generated nutrients before they reach Bow River, a natural (and noteworthy) trout fishery.

Animal impoundments of any kind represent obvious nutrient-surge challenges. In this case, the provincial government of Alberta has stepped forward with a pilot program that could become a model for thousands of similar projects in zoos and various locations associated with the raising of fish, cattle, swine and poultry.

10. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers plans to launch an island for Caspian terns in conjunction with a team headed by Dr. Dan Roby, a wildlife biologist at the University of Oregon. He wants to develop habitats for these birds using floating islands as a cost-effective alternative to the construction of earthen islands.

|

For more information: My ambition in the accompanying text has been to demonstrate the breadth of the available research on floating islands and give you some idea of the diversity of current applications as well as the ways in which mimicking the wetland effect with artificial structures is being considered across the globe. Specific information on the 12 projects covered in the accompanying text can be found on Floating Island International’s Web site (www.floatingislandinternational.com) or by visiting sites sponsored by the indicated researchers, organizations and institutions. B.K. |

Caspian terns are migratory shorebirds and, unfortunately, their historic rookeries are in places where they prey heavily on salmon fingerlings. With the assistance of Dr. Roby and others, the Corps is working to relocate these rookeries to waterways in which other, less-threatened prey-fish species are abundant. When installed, the planned 40,000-square-foot tern island will be the largest floating island in the world, outstripping the 22,000-square-foot tern rookery island launched early in 2009 in Oregon’s Duchy Lake.

11. Owen Mills of the Oklahoma Water Resources Board has developed a proposal to use floating islands to begin the process of slowing down eutrophication of a large Oklahoma reservoir long plagued by nutrient surges associated with chicken farming – but which also supports an exceptional largemouth bass fishery and is lined with more than 5,000 homes and cabins. The plan is to launch floating islands and exploit the wetland effect at nutrient inflow sites and in selected other sites where placement will take advantage of natural circulation patterns.

A single 250-square-foot, eight-inch-thick island provides the equivalent of an acre of wetland surface area, and Mills intends to use the wetland effect to move nutrients up the food chain. Moreover, the oxygen-generating root systems of the floating islands’ wetland plants means that today’s deadly, deoxygenating nutrient surges might soon be replaced by record-setting largemouth bass.

12. The Shepherd Research Center is located a short drive northeast of Billings on the Yellowstone River and also serves as headquarters for Floating Island International. The center is situated at the end of one of Montana’s oldest irrigation ditches and has long been exposed to nutrient surges associated with intense agriculture.

12. The Shepherd Research Center is located a short drive northeast of Billings on the Yellowstone River and also serves as headquarters for Floating Island International. The center is situated at the end of one of Montana’s oldest irrigation ditches and has long been exposed to nutrient surges associated with intense agriculture.

An example of the effects of these conditions is a hyper-eutrophied 30-foot-deep, 6.5-acre pond: Until recently, only the top six feet contained enough oxygen to sustain fish. By circulating large volumes of the stratified, nutrient-rich bottom water through floating islands, oxygen depleting nutrients are being moved into the food chain. In just three months, fish-friendly oxygen levels now occur down to 14 feet.

Bruce Kania is an inventor with a successful track record in the licensing of product concepts in the prosthetic, orthotic, textile and sporting-goods industries. He originated the idea of replicating natural, self-sustaining floating islands while working at his research farm in eastern Montana and runs what amounts to a think tank of independent contractors through his company, Fountainhead LLC of Bozeman, Mont. In his work, he deliberately draws on an enormous talent pool centered in and around the state, finding creative people with the right skills to achieve innovative and marketable results.