Everyone’s Garden

When Chicago Botanic Garden opened its gates in 1972, those on hand faced the same situation as those who come today: They will never see nor experience the garden alike on any two occasions.

For decades, we have personally and carefully watched this remarkable property grow. Along the way, we’ve have shared some of the most profound experiences we’ve ever had in our lives: Both the water elements and the gardens constantly conspire (in the literal sense of the word), breathing as one to create spaces of remarkable beauty, tranquility and diversity. It is truly our slice of heaven on earth.

For years now, we have visited the Garden almost every week to refuel our bodies and refresh our minds. We’ll generally start with a light lunch at the Garden Café, sometimes in the company of a client or with work materials we enjoy discussing in this stimulating environment.

Part of the joy we experience comes from leaving behind our workaday world and its urbanized grid of concrete streets and buildings. In fact, simply being here invigorates our thinking and sorts out our emotions, and the upshot is that some of our very best ideas have come while dining in the café or strolling the grounds. From the moment we enter the property, our moods brighten and the constraints we carry with us are instantly set aside.

A GRACEFUL ESCAPE

As we sit in the café beside a favorite west-facing window or on the adjacent outdoor deck cantilevered out over the pond below, the scene is one of pure bliss: Waterfowl glide gracefully by, and the far shoreline is always a wash of seasonal plants rising gradually to a closely planted stand of majestic Bald Cypresses whose cinnamon-colored bark embraces the Heritage Garden beyond.

This succession of glorious spaces is what the garden has always been about for delighted visitors who move freely from one spectacular environment into another. The pathways guide you through these transitions without fanfare or complication, although the flow from one waterfeature to the next garden display conjures its share of “a-ha!” moments – new discoveries even if you’ve moved along the same paths innumerable times before.

| The Visitor Center and the café’s cantilevered deck (left); at right, the Heritage Garden. |

Periodically, we’ll step off a path and move to the water’s edge to observe birds flying overhead or to revel in the natural sounds that emerge all around us. Thoughts of great artworks come to mind as we wander through the Heritage Garden after lunch, with visions of Claude Monet’s water lilies dancing through our minds.

In the center of this particular space are three pools separated by brick walkways, each watershape containing wonderful water lilies, sacred lotuses and a variety of other tropical aquatic plants. Water cascades over shallow steps that surround each pool, and a fountain spouting up in the center of the composition increases a therapeutic sense of serenity – truly a blissful place worthy of being seen over and over again.

And this is only the beginning.

Indeed, there’s a great deal of space at the visitor’s disposal, as the garden covers 385 acres in all – 81 graced by lakes and rivers and nearly six miles of shoreline, and the other 304 acres festooned by 2,300,000 plants. It’s both a haven and a resource for anyone working in exterior design , particularly those interested in the creative use of water in the landscape in both aesthetic and hydrological terms.

Lake levels are maintained by runoff collected in a 167-acre “watershed” area, backed up by occasional pumping from deep groundwater aquifers during extended dry spells. The waterways are expressions of the nearby Skokie River and draw on an upstream watershed that covers approximately 20 square miles.

| To the left is a view of the Smith Fountain. In the middle is a view across the Crescent Garden. At right, there’s the English Walled Garden. |

The gardens contain ten unique watershape compositions consisting of 30 fountains, waterfalls, streams, ponds and pools itemized on the Garden map. That number actually surprised us as we did research for this article: To us, it had always seemed that the entire space simply teemed with waterfeatures too numerous to count.

That impression is largely due to the site’s ingenious master plan, in which 23 display gardens are all contained on nine islands surrounded by various lakes and rivers. The water appears all-encompassing, in other words, because it literally is almost always in view wherever one happens to be. With every few steps, the view changes and the visitor is impressed anew by the way the land and water gracefully embrace each other in a meandering dance of visual harmony.

INTIMATE STATEMENTS

Within this sweep of amazing settings, you’ll see a number of intimate watershapes that serve to blend landscapes, plants and water in clear but subtle ways. From our first visit forward, we’ve come to see these features as treasured resources unfolding like a three-dimensional idea book. They include:

[ ] The Buehler Enabling Garden, which includes a pair of cascading waterwalls and several elevated pools. [ ] The Outdoor Classroom, with its solar-powered fountain and small pool.|

Landmark Status Owned by the Cook County Forest Preserve and managed by the Chicago Horticultural Society, the Chicago Botanic Garden has a membership of 50,000 – the largest of any public garden in the United States – and now welcomes almost a million visitors a year, making it the second-most-visited public garden in the country. But it’s not just a numbers game: Indeed, the Chicago Botanic Garden is now recognized around the world as a leader in plant-conservation science and serves as one of the nation’s leading teaching gardens. It’s also a vital part of its community, continuing to break new ground in encouraging urban horticulture and providing jobs training through its Windy City Harvest and Green Youth Farm programs. The community returns the favor with contributions both financial and personal: On the latter score, almost 2,000 volunteers assist with all aspects of the Garden’s mission, from planting and propagating natural areas to staffing public programs, educational opportunities and exhibitions – a treasured well of talent and commitment. — S. & R. D. |

There are a few more watershapes not listed in the guidebook, including the pools atop which the Garden’s distinguished collection of 50 premier bonsai specimens seem to float within the recently remodeled Regenstein Center. This structure’s Gallery also has a long reflecting pool on axis with McGinley Pavilion, the Tropical Greenhouses, Exposition Hall, the Esplanade and a viewing terrace overlooking the Great Display Fountain in North Lake.

| At right, a view of the Esplanade Fountain at night. In the middle is the Rose Garden Fountain. At right, there’s the Bonsai Courtyard. |

As part of the Garden’s evolution, some watershapes have been modified, remodeled and even removed since original installation. We especially recall one of the original fountains that stood in the west courtyard of the old Regenstein Center: It had a series of 36 pulsating plumes of frothing water that rose from a granite-paved plaza surrounded by low evergreen plants. We appreciated its calm, cool, meditative qualities but know as well that children were drawn like a magnet to its pulsating spouts.

Although some of these changes have been distressing to us, we recognize that it’s all part of the ever-changing nature of Chicago Botanic Garden – and that our losses tend to be more than compensated for by the fact that the true beauty of the place endures and expands through thick and thin.

PRODUCT OF THE ’60s

The organic, evolutionary nature of the Garden can be traced to its inception and development – a wonderful example of civic leaders and ordinary citizens working toward a common and lofty goal.

|

Multiple Disciplines As environmental designers, we’ve always seen the Chicago Botanic Garden as one of our most valued resources – a place to study, conduct research and take advantage of the facility’s primacy as a center for plant science. Among all of its available resources, we particularly love the Lenhardt Plant Science Library, which houses one of the world’s most outstanding collections of botanical books and serves as the foundation for the library’s renowned Plant Information Service. The goal here is for librarians here to be “go-to guys” when it comes to answering any plant-science question. Last year, in fact, the Plant Information Service handled some 38,000 questions on line and in person. Supporting this unparalleled level of service is the Daniel F. and Ada L. Rice Plant Science Center, which recently opened within the Garden. With its Gold Level LEED certification, it is an example of all that’s being done these days with respect to sustainable design. The new structure includes two green-roof gardens, seven research labs, an expansive herbarium, a new-seed bank, classrooms and seminar halls, offices for research scientists and a public gallery that offers visitors behind-the-scenes glimpses at the processes of conservation science. The Grainger Gallery stands at the heart of the building. This space features interactive exhibits as well as windows into working labs, with everything dedicated to a simple yet essential message: “There is a deep connection between people and plants that can enrich the life of every human being.” — S. & R.D. |

It all started in 1962, when a small, visionary group of leaders of the venerable Chicago Horticultural Society (founded in 1890) gathered together and articulated a dream: They aimed to create a world-class botanic facility for the citizens of the metropolitan Chicago area, but they also wanted it to appeal to garden lovers throughout the country and, indeed, around the whole world.

On its own, the Society had limited financial resources, but its leaders were distinctly well connected in philanthropic and political circles. In those days, of course, almost nothing happened in Chicago or Cook County without the assent of Mayor Richard J. Daley and his well-oiled political machine, but members of the Chicago Horticultural Society were determined and somehow defied the odds.

Behind countless closed doors and in numerous back rooms; in their homes across dinner tables and in restaurants during business meetings; at parties and social events; and through what must have been hundreds of phone calls and arm-twisting encounters, the deal was made and the wheels started turning with remarkable speed.

By 1963, in fact, the trustees of the Cook County Forest Preserve District announced it was leasing 300 acres of its land to the Chicago Horticultural Society for purposes of developing the Chicago Botanic Garden. With the motto Urbs in Horto (Latin for “city in a garden”) inscribed in its charter, what had only been a dream a few months previously began to swing into reality.

Just two years later, the master plan was complete and groundbreaking ceremonies were held in September 1965.

Seven years of intense site work followed. The nine islands were shaped and sculpted – then surrounded by 81 acres of lakes, ponds and rivers. Water elevations and natural drainage swales were set, with everything designed to be self-sustaining based on average annual rainfall and predictable runoff – yet also capable of withstanding a hundred-year storm without flooding. At this time, the course of the Skokie River was reconfigured so that it would flow gently through the Garden’s lakes and waterways.

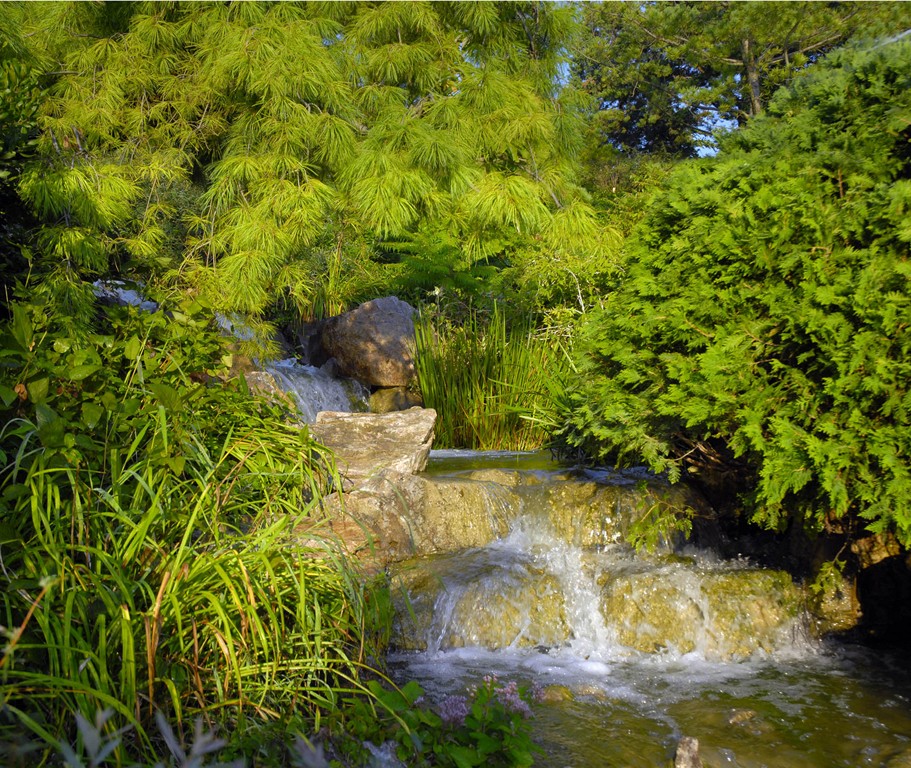

| For anyone interested in the design of naturalistic watershapes and how they can be gracefully integrated with architectural features, the Waterfall Garden is something to behold. Moving beyond the pathways and ponds and into the space’s recesses leads to encounters with the dynamic, dramatic flows of a tall, beautifully crafted cascade. |

With these major site features established, installing the infrastructure of utilities, roads, paths and parking areas began moving forward – all in such a way that there’s no significant intrusion on the space and everything seems to have been there forever. Special attention was paid to conserving and protecting the extant trees, woodlands and native habitats.

By the spring of 1972, the Chicago Botanic Garden was ready for its close-up. Ever since the gates were opened on that first glorious day, a continuing sequence of garden displays, buildings, waterfeatures, programs, lectures, exhibits, expositions, demonstrations and educational events have been worked into the mix in a never-ending crescendo of delightful surprises.

It is this anticipation of arriving each day, each season, each new year, to see and experience what is fresh, what has changed, what has been added and augmented and how nature in all its physical magnificence has blossomed and matured that make this the sort of place that has engaged us on every conceivable level for nearly four decades.

Simply put, the Chicago Botanic Garden is a wonderland of enduring beauty, always changing with the seasons, year-by-year and now through the generations: No two visits are (or ever will be) the same – just as we like it.

Ron Dirsmith is principal architect and co-founder of The Dirsmith Group, an architecture firm based in Highland Park, Ill., with operations worldwide. He and wife Suzanne established the firm in 1971 following employment with the prestigious firms Perkins and Will and Ed Dart, Inc. He has a BS in Architectural Engineering and a Masters in Architecture and Design from the University of Illinois. He is also a Fellow in Architecture of the American Academy in Rome, which for more than 100 years has been a research and study center for America’s most promising artists and scholars. Dirsmith is one of only 172 architects to have been granted this honor. Suzanne Roe Dirsmith, president of the firm, holds a BS in Education from the University of Illinois and a Masters in Education from National-Louis University. She heads the education division of The Dirsmith Group, an effort dedicated to forwarding design and architecture education within the architectural community and to foster new thinking and raise awareness of architecture and landscape design as a blended whole.