Keeping Clean

If there’s one thing all ponds and lakes have in common (beyond the obvious fact that they all contain water), it’s that they’re as different as snowflakes – highly idiosyncratic, often challenging and sometimes almost willful in the way they resist being manipulated.

For the past 35 years, we at Diversified Waterscapes (Laguna Niguel, Calif.) have just about seen it all as specialists in maintaining man-made ponds and lakes and in remediating those that have fallen on hard times and suffer with severe problems. We’ve found that every situation is different and that figuring out what’s going on involves the evaluation of countless variables – some obvious and easy to read, others less so.

For all that, our experience tells us that the serviceability and sustainability of ponds and lakes is for the most part determined long before we come on the scene – even before they are filled with water. When they’ve been designed and installed with a few key principles in mind, we find them to be cooperative and affordably manageable. If a few of the more common mistakes are made, however, it’s a completely different and far nastier tale of woe.

In the course of business, we’ve learned to take holistic approaches to the watershapes under our care, looking at entire systems and seeking to balance key sets of variables we’ve identified. The difficulty is, there are no rules of thumb: What’s needed in one situation may be completely different in another – thus leaving designers and installers with the considerable challenge of anticipating how things will go with a less-than-fully-predictable body of water.

GREEN AND GREENER

To demonstrate what I mean, let’s start by considering the plants designers and installers place around their ponds and lakes. Without question, this is the source of most of the problems we encounter down the line.

That may seem a harsh judgment – and problematic because in the vast majority of situations plants and water are placed in close proximity and it is their combination at the water’s edge that lend these settings much of their beauty. It’s not that we object to comingling water and plants; rather, our issues come when designers or installers force the point and insist upon too much of a good thing. Our concerns in these situations are with plant material falling into the water and the introduction of nitrogen- and phosphate-rich runoff – with the former being the larger issue by far.

| Some ponds simply were not designed for easy maintenance. Indeed, we sometimes encounter nightmare ponds – such as the one on the left, where nutrient-rich runoff from wonderfully green lawns flows unimpeded into the water – a burden so overwhelming that even a good aerator can’t help much. Happily, we also run into well-designed watershapes, such as the beautiful golf-course pond on the right, where the designers and installers knew to include French drains to control runoff and multiple aerators to keep the water circulating adequately. |

As service professionals but also as people with eyes open to beauty, we certainly understand the desire to make ponds and lakes as beautiful as possible by planting material next to and within the water, but we also know there are a couple of simple steps to be taken that can spell the difference between a manageable relationship between plants and water and a complete service nightmare.

Let’s begin with the biggest problem of all: deciduous trees and shrubs that overhang or have been planted right on the water. In southern California, for example, Bougainvillea is extremely common and popular in landscapes and often finds its way into waterscapes – but it’s a species that is constantly reproducing and shedding its leaves and flowers. In addition, they have wicked thorns and really should be kept away from places where people may come in contact with them, including at the water’s edge.

|

Fish on Balance One of the biggest and most common mistakes we see in servicing ponds or lakes has nothing at all to do with how they are designed or built, but instead with the level to which owners have decided to populate them with fish – and the timing of that important step. Quite often, we find that anxious owners will immediately stock a new body of water with bass – great for sport, but they breed quickly and will rapidly overpopulate the water and load it with waste. Moreover, bass are predators, so they don’t do much to benefit the overall ecosystem that is being established. We always counsel patience and a step-wise approach that starts with scavenger fish such as bluegill, mosquito fish or red-ear sunfish: These will keep the bottom clean and the water free of mosquito larvae and other pests or invaders such as snails. In our experience, starting this way can make a difference between a healthy body of water and one that might have to be quarantined. If you think that’s a stretch, quarantines are happening all over the place to cope with invasions of quagga mussels, freshwater mollusks that are taking over rivers and lakes throughout North America. It’s native to waters in Ukraine but has no specific predators here and has been wreaking havoc with ecosystems coast to coast. Foraging fish can keep these mussels from gaining a foothold. If the owner starts a vessel out by introducing predator species that will eliminate foragers, this will allow quagga mussels to take over and eliminate all other forms of aquatic life – not a pretty picture! — P.S. |

Weeping willows also look great near water edge and have the extra advantage of thriving in damp soil, but they’re a major problem when it comes to pond or lake maintenance because they drop huge amounts of material. The same is true of pepper trees, magnolias and jacarandas – all extremely common in our region and each one terribly messy.

Don’t get me wrong: I’m not suggesting that these plants should not be included in the landscape. All that’s needed is to move them back so they don’t overhang the water – and to make certain they can be pruned back if, over time, they demonstrate a tendency to reach in that direction.

A variation on this theme occurs quite frequently in new developments, especially with condominium complexes where the developer wants to sell units as rapidly as possible: Here, there’s a tendency to overplant, putting in too much material and placing whatever is being planted so close together that everything will fill in faster. That’s not a healthy situation for the plants as they mature, so some will need to be removed – a hassle that could easily be avoided simply by planting an appropriate number of plants and keeping them back from the water’s edge.

THE BEAT GOES ON

It’s not just trees and shrubs: Grass can be an issue as well, largely because the tip of a blade of grass contains the most nutrients in the plant and that’s exactly what gets cut off and frequently finds its way into the water. On top of that, these clippings decompose very rapidly in water, and when this occurs in volume a minor problem can become a serious one.

In these cases, all we can do is recommend to landscape maintenance companies that they mow away from the water rather than toward it – and basically do all they can to keep clippings out of the ponds and lakes whose landscapes they service.

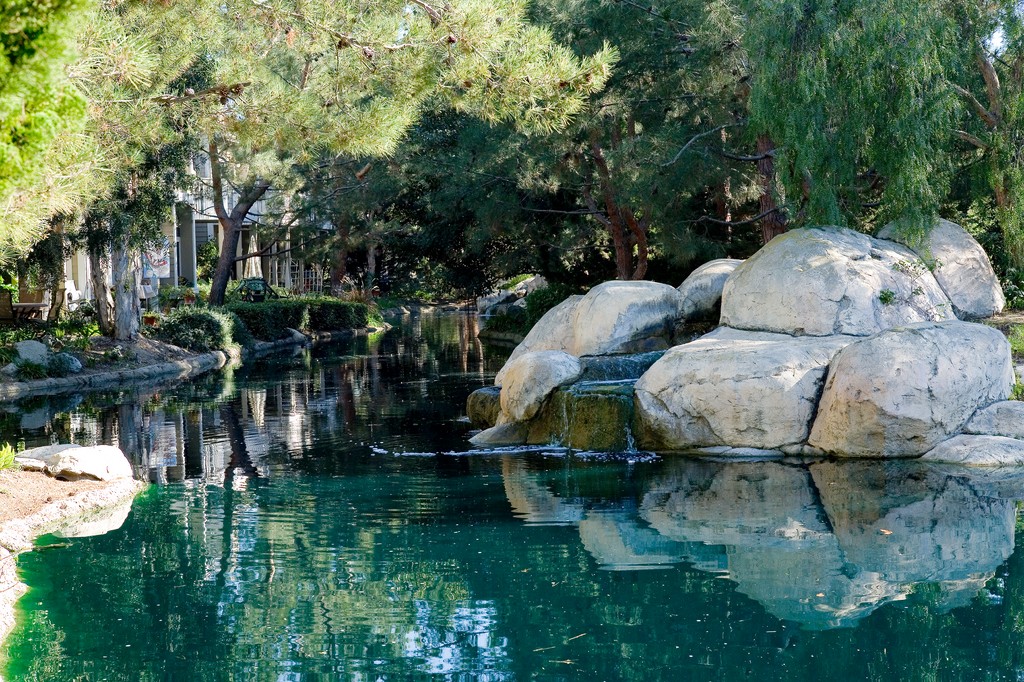

| They can make for great views and artful settings, but placing ‘messy’ trees alongside ponds puts a tremendous burden on these watershapes in the form of debris that just won’t quit. There’s no reason to omit trees of this sort from the landscape, but pushing willows and pepper trees back from the edge so their leaves don’t fall directly into the water can be a big help. |

Problems also arise when lawns flow down to the water and runoff flows with them. The key to minimizing this issue involves placing French drains around the perimeters of ponds and lakes. This will transfer a large portion of the fertilizer-laden water to an outlet away from these nutrient-sensitive watershapes.

There’s also a common misconception that it’s a good idea to dump grass clippings into the water because some species of fish love to eat grass. While that is true of some fish species, it generally overfeeds them and leads them to drop higher-than-usual volumes of organic wastes into the water. In addition, much of the grass will go untouched and will simply decompose in the water. (If I do have a rule of thumb to offer, here it is: Grass clippings should never be dumped in the water – ever!)

Getting back to developers for a moment: All of the above situations with trees, lawns and drainage are worsened dramatically where corners are cut in a pond’s or lake’s circulation system. Compromising on quality may save some money, but it’s a false economy because of the problems that will arise down the line.

|

Say ‘No’ to Ducks Ducks and ponds go together in most people’s minds, and it is indeed part of the pleasure of visiting a pond or lake to watch them come and go. Unfortunately, people tend to focus on welcoming them and, by feeding them, make the ducks less inclined to move along. That’s not a good thing. Resident ducks add tremendous amounts of organic compounds to water that will result in massive water-management problems. A temporary stop is no big problem, but when ducks or geese get comfortable and start nesting – and then people overfeed them – these waterfowl will excrete excessive quantities of waste, get fat and unhealthy and basically sit around, waiting to produce future generations of fat, lazy, quasi-domesticated chicks. Prevention is a two-stroke process: First, don’t provide large nesting areas in the form of cattails or bulrushes; second, do what you can to let your clients know that feeding waterfowl is not desirable. In a worst-case scenario, these sedentary birds can develop avian botulism, which in turn can infect healthier, migrating birds and present the possibility of a true environmental disaster. Worse yet, these birds and their prodigious waste will often result in muddy areas at the water’s edge where E. coli colonies develop. This puts children and even adults at risk and is yet another reason to discourage anyone from feeding ducks, geese or any other migrating birds: They may be great visitors, but they can be lousy tenants! — P.S. |

If there are too few skimmers, if strainer baskets are undersized, if plumbing is downsized, if too few pumps are used, if aerators are eliminated, if filtration systems are inadequate, then any issues related to overhanging trees, nutrient intrusion or any other problem that might arise will be exaggerated. A project might look good for a while, but before long it will run into huge problems with algae and the growth of undesirable plants.

So why not take the pressure off and set trees back from the edge, develop a proper landscape maintenance program and design the watershape to take whatever comes its way? You can’t overwhelm the system and expect good results down the road.

It’s all about striking balances: If you’ve thought things through, you can create a pond or lake surrounded by lush plantings that drop a tremendous amount of material into the water, but the system must be set up to handle that load with respect to turnover rates, skimming and filtration.

Turnover is an underappreciated value in that equation. In most cases, we like to see the water turned over at least once and up to twice a day. That’s easy to achieve in relatively small systems of the sort you see in backyards or business parks. But it’s not so easy when you get to lake-scale systems: Here, you need big pumps and will probably need to supplement filtration with effective aeration to strike the right balance.

BENEFICIAL MEASURES

Now I need to do an about-face and extol the potential virtues of plants. Indeed, one of the best ways to achieve balance in a system with a well-designed circulation system is through proper use of beneficial aquatic and terrestrial plants.

This approach has been well documented in numerous seminars and publications (WaterShapes included), and for good reason: The wise use of constructed wetlands, planting pockets and floating islands will always tilt the balance of a pond or lake in the right direction, especially if the designer or installer knows a thing or two about what works and what doesn’t.

| Trees are only one challenge to the maintainability of pond, stream or lake systems. Excessive populations of fish or the presence of large numbers of waterfowl can be a huge issue, for example, as can inadequate flows across rugged waterfall systems or sluggish velocities in stream systems – especially if there isn’t adequate skimming. The consequences of all of these problems include algae growth and turbidity, neither of which make the water look the way anyone wants it to look. |

Cattails, for example, are quite popular and do a fantastic job of removing heavy metals from soil with their deep root systems. But they are also quite invasive and, if not maintained with some care, can take over an entire pond or lake. Moreover, they do nothing to remove nitrogen and phosphorus from the water column.

Better choices are available, including chara, coontails and various grasses. We use all of them in remediating troubled watershapes, and they have the advantage of not being nearly as invasive as cattails. They also have shallower root systems that enable them to compete effectively with algae in absorbing nutrients from the water.

The right plants can be so effective in absorbing nutrients that we often use them as temporary measures in remediation projects: We’ll put them in place and let them grow to maturity, then we’ll come back and pull them out again. (In large applications, we’ll even go after them with a big harvester.) The advantage this has is that, by removing the plants, we also permanently remove the chemicals they’ve absorbed. This means that the permanent plants we’ve left behind will have a much better chance of keeping up with the load.

|

Skimmer Placement Just because you have a skimmer in a pond or lake does not necessarily mean that it’s doing much good. The key is making certain it’s in the right place. Our firm, for example, is currently servicing a large pond where the skimmer was put in the wrong place. Rather than positioning it on the leeward side facing the prevailing wind, it was positioned on the other side – so debris is constantly blown away from it. The upshot: The pond is chock-full of debris, but the skimmer basket is almost always empty. So what happens is that a heavy load of plant material falls into the pond, saturates and sinks to the bottom, where it decomposes and causes a wide array of problems. In addition, there’s a terrible mess on the side of the pond where the skimmer really should be. Designing ponds and lakes for sustainability and easy maintenance mostly requires common sense. In this case, that means placing the skimmer where the leaves are going to go! — P.S. |

We’re also big advocates of constructed wetlands and floating biofiltration islands, both of which can be beautiful, will help keep nutrients in check and provide wonderful habitats for all manner of birds, amphibians and useful insects.

We also like systems that use biofilters made with perforated pipes buried in layers of gravel – when, of course, they’re properly designed and maintained. As colonies of beneficial bacteria develop within the filtering beds, they absorb nutrients that would otherwise fuel algae growth. But these beds must be deep enough as well as large enough in surface area to be effective.

Biofilters also require some upkeep. As they load with material, they display a marked tendency to form channels through the gravel, in which case the water isn’t being filtered effectively. As a result (and as is the case with the sand filters used with swimming pools), biofiltration beds occasionally need to be disturbed – in their case by raking the soil rather than backwashing. It also helps, once the bed has been disturbed, to inject them with liquid enzymes that will break up solids and encourage bacteria growth.

Again, this is a clear design/installation issue: It’s very important to keep in mind that someone may need to get into the water and rake up the gravel bed – something that can’t be done easily under 20 feet of water, which is why we always suggest placing biofiltration fields in a pond’s or lake’s shallows.

Aerators help as well, not just with turnover but also in the effort to maintain dissolved oxygen at proper concentrations. We often recommend the use of bottom diffuser units because of the way they distribute oxygen from the bottom up and disrupt any pockets of stagnation in the bottoms of ponds or lakes.

BOTTOMS UP

As suggested above, depth is a design/installation decision with which we frequently contend – and it’s not just about great depth, either.

In many cases, in fact, ponds in particular are so shallow that sunlight readily penetrates to the bottom, thus promoting plant and algae growth where nobody wants it. In my view, in fact, deeper is almost always better because deep water will have a tendency to remain clear of unwanted growth.

| When designed with the right combination of positive attributes – adequate aeration, good flow characteristics, perimeter-encompassing French drains and thoughtful plantings – even the water in environments as nutrient-rich as a golf course can be maintained with relative ease. In this case, it means thinking big and integrating all of the facility’s water systems (ponds, streams, waterfalls and even ornamental fountains) to keep the water fully aerated, healthy and clear. |

There are no guidelines here, but we always hope to find that a large pond (with a surface area of an acre or so) will reach a depth of 20 feet or more in spots. To be sure, there are some plants that will take root and grow at that depth – especially if the water has a high degree of clarity – but for the most part plants have a hard time at levels below six or eight feet of depth.

True, areas of deep water can present problems with thermal stratification that can impede circulation and lead to problems with poor oxygenation, anaerobic conditions, bacterial decomposition and rotten-egg smells, but the deployment of aerators will generally take care of these issues. (We prefer to see dissolved oxygen levels at six parts per million or more, especially at the bottoms of the watershapes under our care.)

|

Roofs and Rain Gutters In many cases, runoff from rooftops and gutters is directed into a pond or lake – and in many cases, we’ve seen flooding as a result of insufficient capacity. If you set things up this way, you must make certain the the watershape’s capacity is ample enough to handle the additional water. If it’s a retrofit or that capacity simply isn’t available, you’ll need to make sure the drainpipes themselves are large enough to provide the surge capacity you need. — P.S. |

There is no doubt that managing ponds and lakes can be a complex and difficult task – or that the design and construction of these bodies of water has a huge influence on their health and long-term performance.

In this article, I’ve outlined a number of factors that should be considered as these vessels take shape. I also recommend checking in with the North American Lake Management Society (www.nalms.org), an organization that boasts among its membership some of the world’s top researchers and scientists working in the field of aquatic-system management.

As I see things, it’s vitally important that ponds and lakes remain healthy both because of the beauty and value they add to our lives and landscapes and because the consequences of letting them go bad can be so dire and even dangerous. That’s why I believe you can never have too much information when designing or installing a new pond or lake: The work you do is important, now and for future generations!

Patrick Simmsgeiger is president of Irvine, Calif.-based Diversified Waterscapes, an aquatic-service/chemical-manufacturing firm that works on ponds and lakes in southern California. While studying business in college, Simmsgeiger realized his true ambition in researching and developing products for use in aquatic environments and worked for 11 years after graduation for a company that produced chemicals for use in industrial, agricultural and domestic water-treatment programs. Later, he opened his own facility to produce what he called the “Formula F-Series Aquatic Treatment Products.” He founded Diversified Waterscapes in 1988 and, in addition to his extensive experience in the development, restoration and maintenance of aquatic environments, is also licensed by California’s Department of Agriculture as an Aquatic Pesticide Applicator and is a Certified Lake Manager.