Artful Restoration

Back in 1949, a prominent couple living in Litchfield County, Conn., decided they wanted to build a contemporary-style home that would stand out among the classically styled residences that marked the area. After conducting extensive research, they retained the renowned Bauhaus architect and Modernist artist Marcel Breuer.

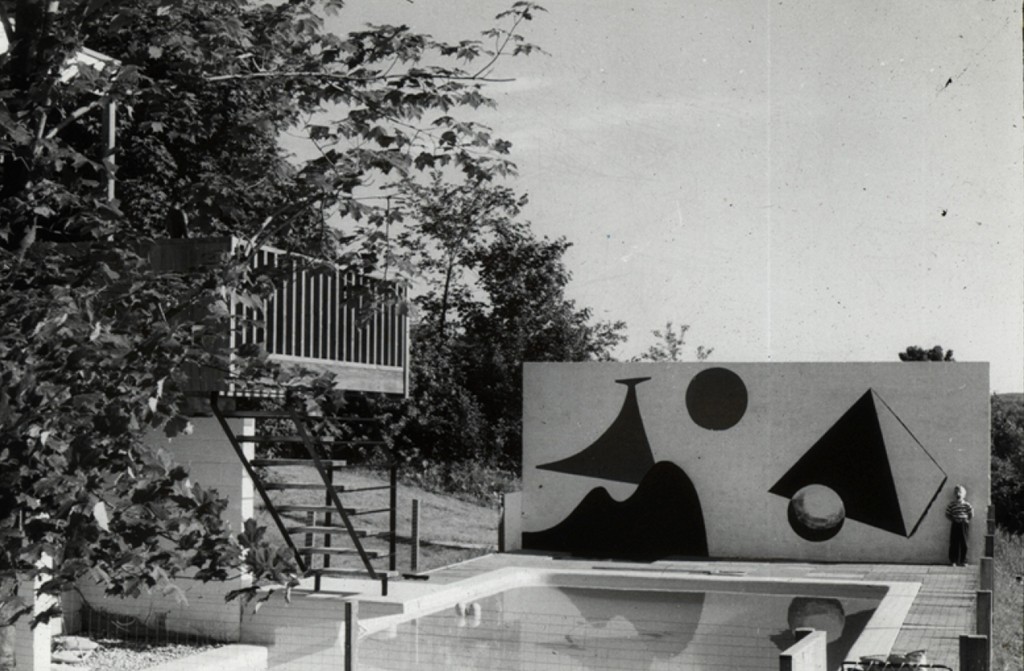

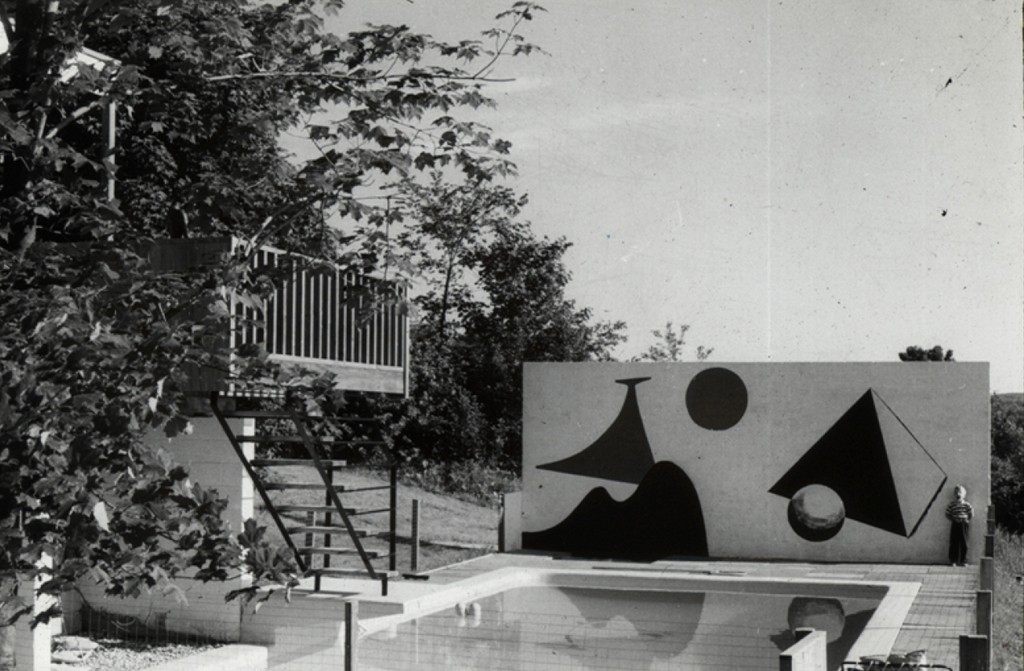

The home Breuer eventually designed for Leslie and Rufus Stillman pays testimony to the stark beauty of minimalism: The daring, box-shaped, two-level structure featured an array of contemporary elements and appointments, not least of which is a large, rectilinear swimming pool accessed by a dramatic, cantilevered staircase from the home’s upper level. (Things worked out so well here, by the way, that this was just the first of three Breuer homes commissioned by the Stillmans.)

The couple avidly collected modern art, so the home became a showplace for a number of original pieces by several of the mid-century period’s greatest artists, including Alexander Calder. Although perhaps best remembered today for inventing the mobile, Calder was asked in this case to paint an original mural on a large block wall set above the deep end of the pool. The results were, in a word, spectacular.

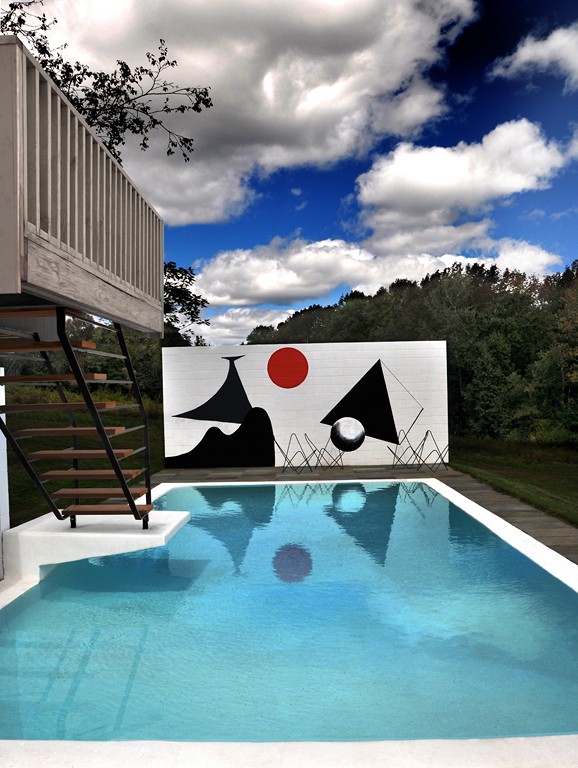

But let’s fast-forward 60 years: By 2010, the Stillman House was in need of restoration, and even the vivid Calder mural had cracked and eroded from exposure to the elements. Happily, this proved a turning point, as the property’s new owners announced their intention to completely restore the house and return it and all of its features to original condition.

A RARE OPPORTUNITY

We at Drakeley Swimming Pool Co. (Bethlehem, Conn.) were contacted by the homeowners at the recommendation of a mutual friend at some point after the Stillman House restoration project had begun. They told us that they had been working with a local plastering company who offered the suggestion that all the pool really needed was a new plaster finish.

| When we arrived on the scene, the pool still held water and was structurally sound, but it had suffered in other ways through its 60 years of service and was clearly in need of aesthetic and mechanical attention. |

They wanted a second opinion, and we were happy to oblige. What we found on site was a raw concrete structure that had been treated with no more than a cement-based sealer – no plaster at all, no waterline tile, no coping and no more than an unusual rolled-edge detail at the top of the pool. The plastering company had recommended a white, exposed-aggregate finish, and the homeowners were rightly concerned that this wouldn’t look at all like the original, especially at and above the waterline.

And anyway, our site review indicated that this project needed to be about much more than a replastering job: We saw the need for a new equipment set, revised plumbing and attention to a host of other details – but nothing much out of the ordinary for a pool that had its original cast-iron plumbing, fittings and bronze fixtures. We noted that at some point a heater had been added, but beyond that, we saw no signs that anything had been touched in a serious way since 1950.

The pool itself had been dry-gunned and measured 18 feet wide by 36 feet long, with the deep end at eight feet (next to the mural wall) then rising sharply to a shallow end, where we found an unusual 18-inch depth. The structure sits on a terrace overlooking a beautiful wooded valley that stretches out beyond the mural wall, and perhaps the most interesting feature in a simple design was the cantilevered landing that offered access to the pool. (This was, by the way, a design detail Breuer revisted 15 years later in creating the entryway to the Whitney Museum in New York.)

| It helped significantly that the early history of the house had been well documented and thoroughly photographed. This rich background answered many questions and sped the process of deciding just what needed to be done. |

The pool’s shape was clearly simple, but this was a progressive watershape for its day and bears witness to an early application of dry shotcrete in pool construction (including the rounded floor-to-wall transitions).

We also had to work with the fact that the homeowners initially thought that all the pool needed was some cleaning up to become operational again. As we dug deeper, we had to inform them otherwise: The pool needed complete renovation and updating, we said, and restoring it to its original appearance would take the same kind of care that was being applied to the home itself.

ORIGINAL INTENT

At the initial meeting with the client, it was unclear to us that the project was about restoration rather than renovation. As a result, we had been considering a number of ideas that would have altered (and, we thought, enhanced) the general appearance while staying close to the original program.

We also talked with some colleagues about the project – including, for example, David Tisherman of David Tisherman’s Visuals, Manhattan Beach, Calif., who suggested extending the pool around and past the mural wall to create the impression that the artwork was floating on the water.

I actually proposed this idea to the homeowners, who politely redirected my thinking and made it clear that the work being done throughout the entire property was aimed bringing things back to original condition to the greatest extent possible – pool and mural wall included. This meant we had to shift gears, but it did nothing to dampen our enthusiasm for the tasks at hand.

| With exact restoration in mind, we proceeded with extraordinary care in selecting materials and finishes to get the job done. This included preparation of various sample boards for the gleaming interior finish and sourcing a replacement for the old-style skimmer, but it also involved finding appropriately sleek lighting fixtures – an amenity not originally included in the pool. |

But before we could get involved with the mural, we had to set things right with the pool, which needed all sorts of attention and carried its own challenges. First, for example, we had to assess its basic structural integrity. It hadn’t been used for several seasons and had been blackened by dirt and debris. Once we cleaned it up, we found some surface cracks, but otherwise and overall, it was structurally sound.

The plumbing was another story: It all had to be updated while avoiding new penetrations or other structural reworking. The same was true of the equipment set, which needed upgrading with energy efficient pumps, modern filtration, a new heater and a control system.

One of our first challenges had to do with the skimmer. What we found was an old-style, no-niche fitting that extended from the wall and connected to a bobbing-style unit (once common but rarely seen these days) supplied by Aladdin Equipment Co. of Sarasota, Fla. Given the rolled edge, we knew we wouldn’t be able to use a modern substitute without completely disrupting the original appearance.

This meant that we’d either have to fabricate an exact replica of the original skimmer or find one on some supplier’s back shelf. Playing a hunch, I contacted a friend at Paddock Pool Equipment (Rock Hill, S.C.), which was in business back in the ’50s and, I hoped, might have some useful information in its archives. I described what I was looking for and asked if they might know of such a product or, better still, might have it in stock somewhere.

My friend said he’d look into it and soon called me back with a report that they found two on the shelf. I purchased both, knowing that they might be the only two such skimmers of their kind available anywhere. One was in mint condition; the other had become discolored through the years. We decided to use the pristine unit and kept the other as a backup.

RECEATING A CLASSIC

Luck was on our side, it seemed, and stayed that way for the rest of the project.

We knew, for example, that local building codes would not allow the skimmer to be the only suction source, so we had to rework and split the main drain to bring things up to current safety standards. This would mean either digging under the pool or coring out the original drain – and probably both.

As we started pulling things apart, however, we noticed that at some point someone had inserted a run of black polyethylene piping down to the main drain, using the original cast-iron pipes as a sleeve. We pressure-tested the poly line: It held up well, so we were able to use it and, as a result, all we had to do was cut into the shell to create the split main drain. We also used a variable-speed/variable-flow pump (made by Pentair Water Pool & Spa, Sanford, N.C.) that includes an onboard SVRS device as another safety layer.

(In removing the old main drain we made what was, at least to us, a truly amazing personal discovery: Inside we found a bronze Paddock fixture that made it certain the pool had originally been built by the grandfather of Bill Drakeley, our company’s president. He was the only custom builder in the area at that time and was the only one in the region who used Paddock equipment.)

From that point on, replacing the plumbing was a simple matter of opening up the ground behind the bond beam and running a new plumbing loop. We had to make a few new penetrations to add some return lines, concealing them as best we could as white, flush-mounted fittings, but by and large what we did was minimally intrusive both in physical and especially in visual terms.

The only true alteration to the original design had to do with adding a pool light on the house side of the watershape to give the setting some added drama at night. We core drilled the niche and powder coated the entire assembly in white so it would blend in with the surface. The light came from Hayward Pool Products (Elizabeth, N.J.) and was chosen for the style of the lens, which seemed to fit best as part of the contemporary design and may well have been something the architect and artist might have used if it had been available when the watershape was constructed.

As all of this basic restoration work moved along, we began to get increasingly excited by the prospect of the project’s main event and the reconstruction of the wall and restoration of the Calder mural.

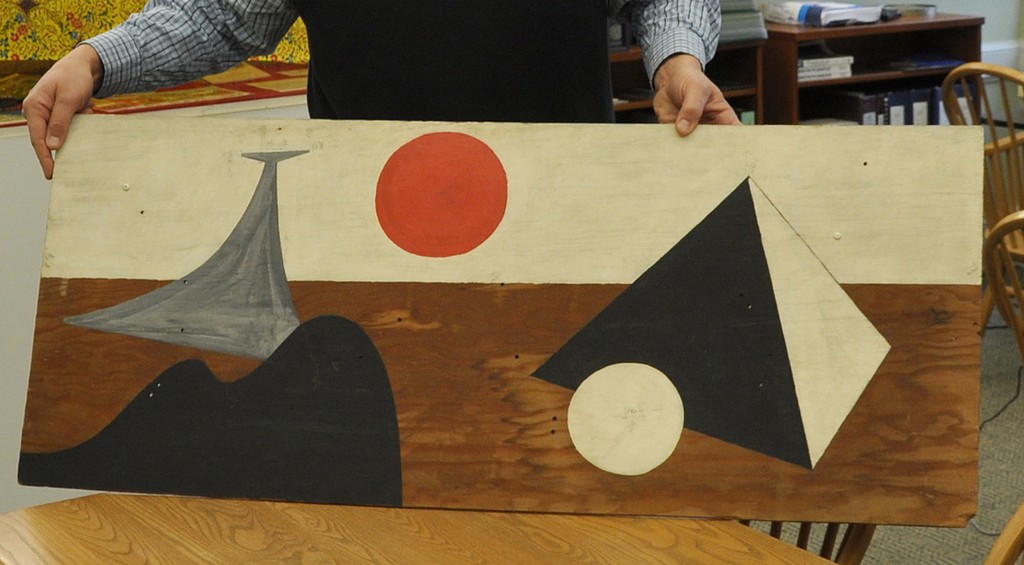

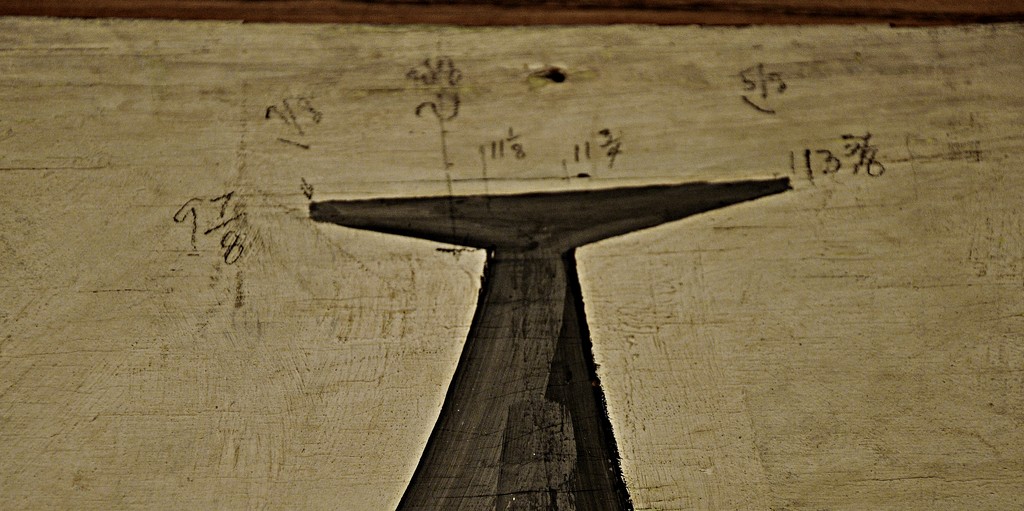

| Before painting the mural in 1950, Alexander Calder prepared a full-scale mockup for client approval. We gained access to that plywood panel through the local historical society, and it was amazing to see how meticulously the artist had recorded measurements and so clearly defined the various spatial relationships. |

The mural had been painted on a block wall 12 feet, six inches tall and 22 feet wide. The wall’s footing, unfortunately, had been set in gravel and had gone out of level by about four inches in the course of 60 years. As a consequence of this general decline, water had entered the block structure at the top of the wall and had penetrated through the block, lifting the paint and substantially destroying the mural’s surface.

STEP BY STEP

The painstaking restoration process was undertaken with the help of the Calder Foundation and with the aid of contemporary photographs as well as information on the original dimensions and even on the paints the artist had used.

Indeed, the design and construction of the house had been documented in great detail (including photographs I found on a visit to the Litchfield Historical Society of a mock-up and full-scale rendition made by Calder for the Stillmans’ approval) – and in general we followed every lead: The current homeowner’s passion for Breuer and Calder was so great that there would literally be no unanswered questions.

Our part in this was advising on rebuilding the wall, which was upgraded with 48-inch deep footing designed to do a much better job than the original of withstanding local freeze/thaw conditions. The area was also graded and a proper drainage system installed to protect this base before every one of the carefully marked blocks was put back in its exact, original position.

| Fully restored after long years of deterioration, the pool and mural at Connecticut’s famed Stillman House have regained their former glory and once again offer testimony to the artful collaboration of an ingenious architect and a brilliant artist. |

Once the wall was up and we’d sealed it with base coatings to create a proper texture for application of the mural, the homeowner set about recreating the bold yet simple geometric forms Calder had used to link his work to views of the valley beyond.

The wall actually obstructs a large portion of a wonderfully scenic view of forest-covered hillsides – an incredibly bold step on Breuer’s part, but one that Calder eased by incorporating representations of distant contours into his composition in a way that effectively comments on, extends and engages the view.

There’s an orange sphere, for example, that represents the sun hanging in a roll of the hills, along with a lower sphere that represents the moon, a triangle that represents the mountainous terrain and a conical shape that suggests a volcano (a truly exotic touch, as there are none in the region).

In other words, the mural is both a representation and a part of the landscape view – a pioneering work of environmental art that fits perfectly within the context of Calder’s exploration of more mobile forms that participate in their settings.

Jeffrey Boucher is vice president and managing partner of Drakeley Pool Co. and Drakeley Industries in Woodbury, Conn.. A 17-year industry veteran with expertise in all forms of pool design, construction and service, Boucher is an expert in green technology and alternative sanitizers and has contributed to industry articles written on these topics. He also has a background in design and photography, and his work with Drakeley Pool Co. has been featured in national magazines including Cottages and Gardens, Fairfield Country Home and Luxury Pools. He is a participant in the Genesis 3 schools and is pursuing membership in its Society of Watershape Designers; he is also a member of the Nikon School of Photography and the American Shotcrete Association.