The Eternal Joy of Water

In this delightful and insightful essay, Anthony Archer Wills takes us on a far-flung journey into bathing traditions and the use of water in fine art. A pursuit, he explains, that is both exciting and worthwhile because to create with water is to understand its profound influence on our forms of creative expression, emotion and even spirituality.

In this delightful and insightful essay, Anthony Archer Wills takes us on a far-flung journey into bathing traditions and the use of water in fine art. A pursuit, he explains, that is both exciting and worthwhile because to create with water is to understand its profound influence on our forms of creative expression, emotion and even spirituality.

I’ve long believed that our earliest ancestors were probably quick to realize water’s potential for fun and fascination, and we have exploited those qualities ever since. Evidence of both the pleasures and profundity of water can be found in countless places throughout recorded history.

People have always respected the power of water, recognizing the element’s strength and potential to destroy or create, and out of that grew a great reverence. Water has been worshiped and bestowed with deities — from Nun in ancient Egypt, the personification of the primeval waters from which the universe was created, to the beautiful Naiads of Greece and Rome, water is both essential and constant, and has been influencing us from our birth as a species.

This is why I contend that understanding the innate connections between water, nature, the landscape and human experience is an essential set of concepts for anyone who endeavors to create bodies of water for display and immersion.

It is quite simply why we do what we do in our struggle to tame water as a design element.

BATHED IN TRADITION

The human relationship with water as a cultural manifestation arguably begins with bathing. It’s depicted in the frescos in the Etruscan Tomb of the Augerx at Tarquinia (c. 530 BC) and the baths at Maen-de-Daro, which are believed to be 4,500 years old. Archeologists have discovered baths and depictions of baths among the remains of many ancient civilizations – in Babylon, Egypt, Europe and South America.

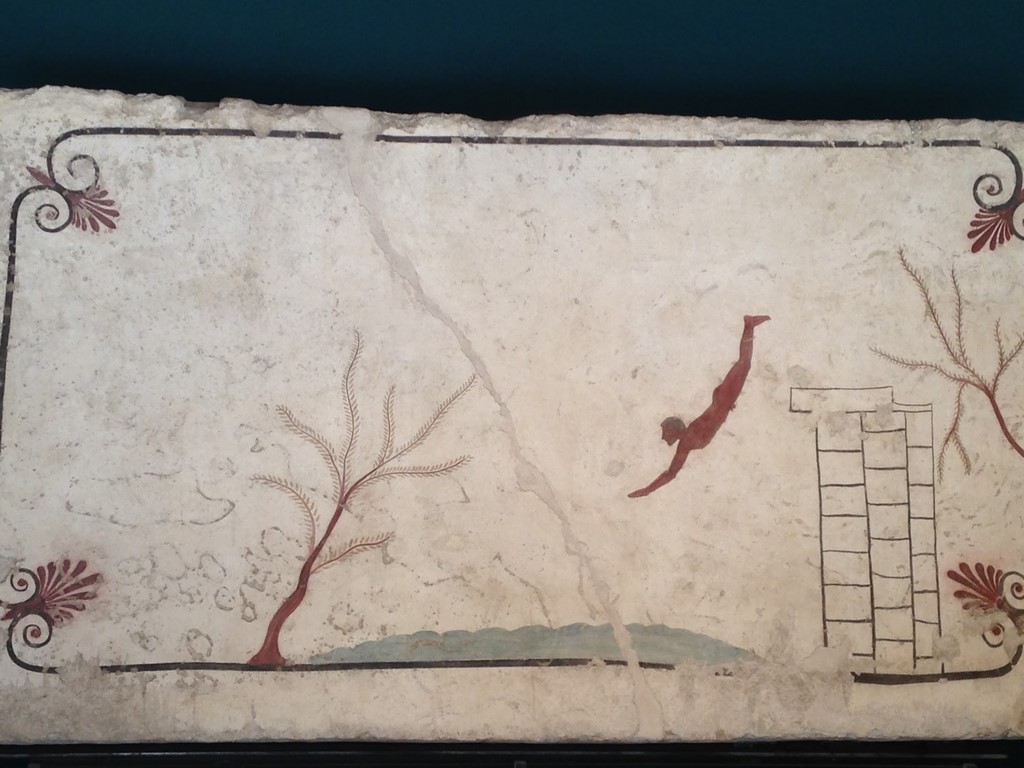

I love poking around ancient structures to see how people enjoyed water. In Paestum in southern Italy, for example, there is a delightful painting on stone from 500 BC of someone experiencing the thrill of diving; and, amongst the ruins one can even find the remains of heated swimming pools!

I love poking around ancient structures to see how people enjoyed water. In Paestum in southern Italy, for example, there is a delightful painting on stone from 500 BC of someone experiencing the thrill of diving; and, amongst the ruins one can even find the remains of heated swimming pools!

Being able to swim was considered a status symbol in ancient Greece, while all classes of Romans reveled in swimming and bathing. For those who could not afford a private bath, great public bathing facilities were built. The baths at Caracalla, constructed around 200 AD, are believed to have accommodated 1,600 bathers.

Baths became gathering places and essential to everyday life, both hygienically and socially, even politically. Aristocratic ladies of Rome would entertain guests while spending hours on end in their baths clad only in their jewelry.

Turkish and Nordic peoples are also known for their steam baths and saunas, and the sensual rituals and practices involved therein.

On the other side of the world in northern Japan, it was common for entire families to spend days basking in hot baths. Perhaps they took their cue from the Macaque monkeys that spend hours surrounded by deep snow in the hot springs to de-stress! In these cultures, bathing was an integral part of daily life, and we find evidence of this importance throughout art and recorded history.

All are examples of humans striving to recreate the pleasure of water found in nature. We bathe in water, swim in it, float and sail on it, and we play with it. Even a garden hose pipe can offer children hours of fun. When water is frozen, we venture onto it to take advantage of the new recreational possibilities it has to offer: ice skating, hockey, and ice fishing, to a name a few. Snow entices entire families outside to build snowmen, go sledding, ski, and pelt each other with snowballs.

All of this is why multi-billion-dollar industries have risen with the sole purpose of exploiting water as a medium for sport and recreation.

WATER IN ART

Nowhere is the essence of our relationship with water, the awe and enjoyment of water, better expressed than in our finest works of art and self-expression. Indeed, the human relationship with Mother Nature and interpretation of her moods is both an inspiration and challenge to artists, musicians, writers and philosophers, water is a big part of that.

Not surprising, the presence and role of water is integral to many of the greatest of works. It’s a creative modality that traverses time and culture, as pervasive as the sky and essential and the air we breathe.

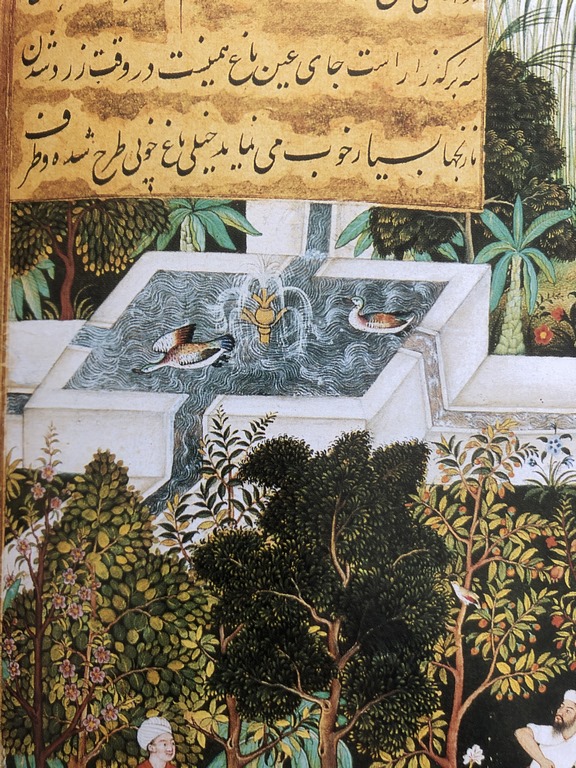

In numerous Persian and Mughal miniatures we see depicted the “Quartered Garden” or “Chahar bagh.” This design is based on the canal, which was essential in bringing water from the mountains into the arid desert regions. By adding a sluice across the flow, the water could be also be diverted to flow off at right angles giving rise to this design.

In numerous Persian and Mughal miniatures we see depicted the “Quartered Garden” or “Chahar bagh.” This design is based on the canal, which was essential in bringing water from the mountains into the arid desert regions. By adding a sluice across the flow, the water could be also be diverted to flow off at right angles giving rise to this design.

The water would often terminate in an octagonal pond in the Sultan’s palace from which it would flow in four directions down narrow rills, thus dividing the garden into four. These beautiful formal Islamic gardens can be found in countries from Morocco to India.

One of the best surviving examples of this design which is enchanting to visit is at the Alhambra Palace and Generalife Garden, Granada in Spain, built around 1350.

(In his wonderful book, “Gardens of Paradise,” historian John Brookes details this great design tradition in a most enthralling read.)

In medieval Europe, the Church was the greatest patron of the arts and naturally scripture was the primary subject matter. Yet, even there we find enchanting glimpses of gardens and bodies of water amid predominantly religious imagery.

In Renaissance paintings we find tantalizing glimpses of lakes and rivers that embroider classic and liturgical imagery, such as Raphael’s Madonna of the Goldfinch from 1506. Later in the 15th Century, the Van Eyck brothers included fountains in their devotional pictures, symbolizing the water of life. In these exquisitely detailed works, plant forms and landscapes were depicted with reverence and astonishing virtuosity. The Adoration of the Lamb on the Ghent altarpiece, completed in 1432, and the Madonna of the Fountain (1439) are classic examples.

As artists were granted more freedom in the attitudes of some religious leaders, they felt more confident to indulge their predilection for landscape and very often, waterscape painting. Gradually, water, mountains, and forests became acceptable motifs in their own right, independent of historical or religious connotations. We begin to see nature captured purely for the sake of its own beauty and wonderment.

As artists were granted more freedom in the attitudes of some religious leaders, they felt more confident to indulge their predilection for landscape and very often, waterscape painting. Gradually, water, mountains, and forests became acceptable motifs in their own right, independent of historical or religious connotations. We begin to see nature captured purely for the sake of its own beauty and wonderment.

INTO NATURE

This is why I’ve always loved the lively winter scenes by Pieter Breughel the Elder (1525-1569) and Hendrick Avercamp (1585-1634) in which peasants revel on frozen lakes beneath atmospheric skies – a perfect illustration of water’s recreational side, and the role it played in the enjoyment of everyday people.

John Constable (1776-1837) and William Turner (1775 – 1851}, depicted the power and beauty of limpid waters with reverence and a passionate zeal previously only accorded to religious subjects. Earlier Claude Lorraine (Pastoral Landscape, 1645) and Nicholas Poussin (1594-1665) had painted the idealized landscapes of classical mythology, placing in the scenes the nymphs and goddesses of ancient Greece and Rome.

These paintings and others inspired the great English landscape architects of the 18th Century. Is this the true inspiration and origin of modern watershaping?

These paintings and others inspired the great English landscape architects of the 18th Century. Is this the true inspiration and origin of modern watershaping?

One favorite painting of mine, of which I had a large print hanging in my office, was of beautiful Ophelia floating down a stream by Sir John Everett Millais. In the clear water, every plant such as the Myosotis palustris, Ranunculus aquatilis and Sparganium erectum is faithfully painted and easily recognizable.

It’s interesting to note, that in another example of water’s ubiquitous influence, French painters Renoir and Monet were painting their sensual pictures of nubile girls and water lilies at about the same time, both in a completely unabashed manner absent of pretense or historical or literary reference.

Many years ago, I was delighted when I discovered a French impressionist painter, Gustave Caillebotte (1840-1894) whose shimmering paintings of water, complete with waterlilies from his friend Latour-Marliac of Le Temple-sur-Lot, were full of light and color, and gardens opulent with bright herbaceous borders, and vegetation of every conceivable green.

The tradition of water in visual art continues into the 20th Century with the works of modern artists such as David Hockney. In his 1965 painting “Sunbather” a nude male figure, lying on a beach towel next to a pool, is transfixed by the rippling waves. I love how the water occupies most of the picture – as though it fills the mind of the spectator.

In many ways, whether we realize it or not, we have all been witness to water’s constant hypnotic powers – be it in art or in our life experiences.

BEYOND THE CANVAS

Water is as great a source of inspiration to musicians and authors as it has been to painters. No composer has portrayed the excitement of turbulent water and weather better than in Rossini’s”William TellOverture,” which powerfully evokes the charged heaviness of an approaching storm, and then the thunder’s crash followed by the rain-washed calm as birds recommence their songs. Schubert’s “Trout Quintet” reflects a quieter mood, evoking quiescent depths below a rippling surface, but to no less emotional impact.

Johann Strauss was similarly inspired by the steady calming rain at Bad Ischl in Austria. He described his perfect holiday as, “. . . always rain, the sound of the brook and a well-heated room where I can write music.”

Johann Strauss was similarly inspired by the steady calming rain at Bad Ischl in Austria. He described his perfect holiday as, “. . . always rain, the sound of the brook and a well-heated room where I can write music.”

Claude Debussy strove to give musical expression to the sea in “La Mer,” a powerful and brooding piece that taps into our primal fear and love of water.

In literature, we also find numerous examples of water’s influence on the atmosphere and landscape. As far back as the 8th Century in the epic saga “Beowulf,” the sinister mere is described as an appropriate home for the monster Grendel and his dam.

Later, in the 15th Century, Chaucer paints a very different picture, offering insight into our ancestors’ sensual delight in their water gardens.

A garden saw I of blosmy bowes

Upon a river in a grene mede,

There as ther swetnesse everymorey – now is

With fluores white, blewe, yelwe and rede,

And colde welle – stremes no thying dede.

That swommen ful of smale fisches lighte,

With fynnes rede and scales silver-brighte.

Even if you don’t fully grasp the literal meaning, the emotion felt by the water is self-evident.

A few centuries later, Tennyson, in “Crossing the Bar,” uses a flowing river as an allegory for the river of life so that the point where the river meets the sea signifies his death. The bar is usually choppy, yet he hopes his death will be a peaceful affair, a gentle wave that moves unnoticed from one life to the next.

Perhaps because we gestate in water and are made of water, and depend on water for our survival, it is inextricably part of our spiritual, emotional and artistic landscape. It’s as profound as baptism, as indulgent as a bubble bath and as inspiring as a visit to Monet’s Giverny.

Next time, we’ll take a journey into the use of water itself as an artistic medium.

Anthony Archer Wills is a landscape artist, master watergardener and author based in Austerlitz, N.Y. Growing up close to a lake on his parents’ farm in southern England, he was raised with a deep appreciation for water and nature – a respect he developed further at Summerfield’s boarding school, a campus abundant in springs, streams and ponds. He began his own aquatic nursery and pond-construction business in the early 1960s; work that resulted in the development of new approaches to the construction of ponds and streams using concrete and flexible liners. The Agricultural Training Board and British Association of Landscape Industries subsequently invited him to train landscape companies in techniques that are now included in textbooks and used throughout the world. Archer-Wills tackles projects worldwide and has taught regularly at Chelsea Physic Garden, Inchbald School of Design, Plumpton College and Kew Gardens. He has also lectured at the New York Botanical Garden and at the universities of Miami, Cambridge, York and Durham as well as for the Association of Professional Landscape Designers, from which he received the 2013 Award of Distinction. He is also a 2008 recipient of The Joseph McCloskey Prize for Outstanding Achievement in the Art & Craft of Watershaping.