An Equine Retreat

It is rare that any of us are asked to build a swimming pond for horses. But why not? They are admittedly much bigger than Koi and certainly larger than humans, yet I am assured they are considerably cleaner than dogs and genuinely do benefit from the leg-relieving buoyancy that comes with immersion in water.

The first pond I built for equestrian swimmers came along in the late 1970s – just after I’d completed several large gravel-filtration ponds for trout: It seemed at the time that the same principles that worked so well for indoor aquariums and fishponds could be adapted to purify water for almost anything or any body, so all sorts of interesting possibilities were being explored.

I’d arrived at my first equine project very gradually, beginning with an aquarium I maintained in my teens, then followed by building my first goldfish and Shubunkin ponds in 1963. There was always a goal to arrive at crystal-clear water that resulted in friendly rivalries among a group of us who had ponds.

But there is more to fish ponds than water clarity alone: As I’d learned, the main challenge in building watershapes for anything other than finned, feathered or amphibious creatures is to prevent penetration of the liner by claws, paws or hooves. Indeed, protection is even a significant concern with fish-only ponds given the number of gardeners I’ve known who have gone berserk with spades and pitchforks in attempting to dig out choking clumps of water lilies. It seems that people will stop at nothing – which too often has led to my having to crawl about in mud trying to locate and repair leaks.

DOWN ON THE FARM

Suffice it to say that these considerations and more take on greater urgency when one approaches a truly grand-scale horse pond – which I did not long ago for a large farm and equestrian center situated in Germany near the Bavarian Alps.

The property covered a few hundred acres and was extremely well-equipped with modern machinery. There was a large Volvo excavator along with several small excavators – all with quick connects and hydraulic swivels. There were also high-speed tractors with large trailers on floatation tires as well as every kind of chain and hand tool a pond builder could desire. And the owners put it all at my disposal along with farm personnel!

Beyond that, the property also encompassed stone yards filled with ancient blocks of tufa stone – and, of particular interest, great sheets of rubber floor matting designed for use in stables.

My first task was to spend a few days talking with the family and exploring the farm: One needs to be quite sure of the hopes and dreams of one’s clients to win their confidence and steer them through any pitfalls, delays or surprises that might arise. As we came to know each other, they informed me that they wanted a pond in which the horses could swim and take the weight off their legs. But this was also to be a fire pond as well as a place for family members to swim in the heat of summer and skate in the dead of winter.

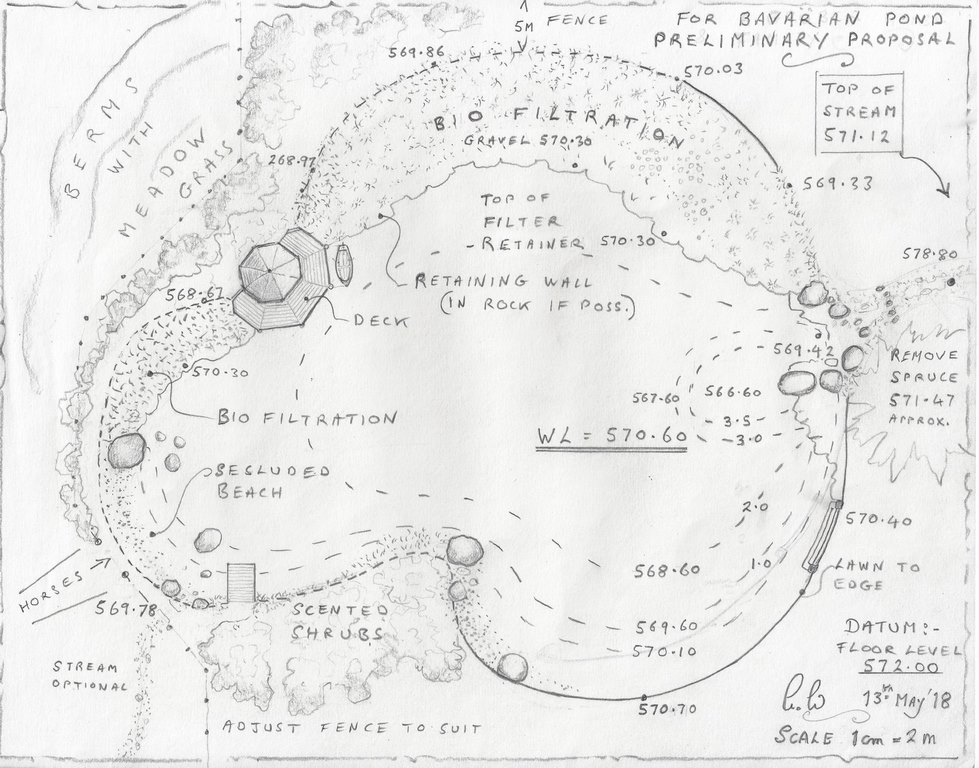

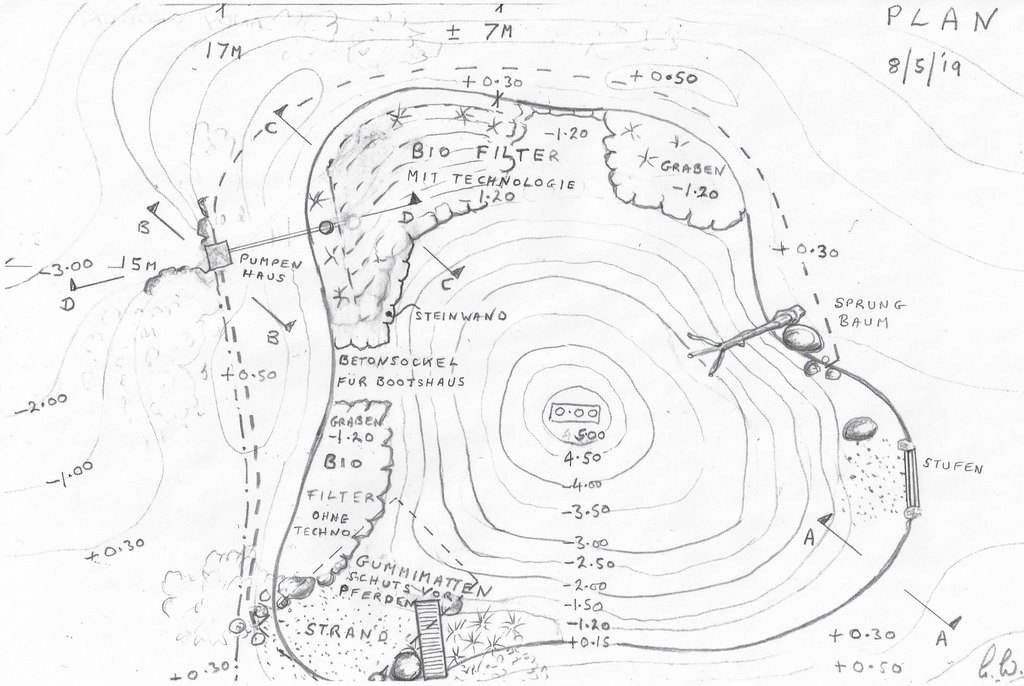

| The farm was no small enterprise and provided us with ample space to include a large-scale horse pond. At top left is the site as we first saw it. Later, we placed rope to mark out the pond’s basic shape (the large spruce would have to go!), then the topsoil was stripped off to make way for excavation and contouring (top middle left and right). Along the way, I prepared a preliminary sketch that was then followed by a string of in-process drawings (with very basic notations in German) to guide farm personnel. One of the pond’s future bathers surveyed the scene, no doubt with skepticism. |

In addition, the mother of one of the clients lived on the farm and was the most passionate of all of them about horses. She added the idea of swimming and sunbathing beside a shoreline close to the farmhouse – a fact that led me to plan on her own sheltered and secluded beach as a place where she could relax unobserved.

Owing to the expansive landscape, I advised them to think in grand terms and make the pond as large as possible to fit into its surroundings and hold its own amid the farm’s various structures. There was also a bonus, I told them, in that a large watershape would reflect the mountains from one direction and the farmhouse from the other. With ponds such as this one, I explained, big is beautiful.

On returning home from Germany after having developed a few concept sketches with the clients, I came up with more-detailed drawings that would enable them to get outline-planning permission from the town. But even then, we continued to massage the design. I suggested that before my next visit, they should strip off all the topsoil and save it close by – but not where it might get in the way of our subsequent work.

When my wife and I next returned for the main part of the build, there was a clean field site, free of topsoil and ready to go.

GRAND HORIZONS

For the duration of our stay, the clients put us up in great comfort at Die Post Landgasthof in Berg, Germany – which they happen to own. The journey each morning and evening to and from the job site was idyllic: We were never bored with the 40-minute drive, which passed through picturesque villages with fresh, snow-capped-mountain views at every turn. It was one of the most picturesque commutes I have ever enjoyed.

The weather, however, was against us from the start – including snow and heavy rain. So I spent a lot of time in their kitchen, drinking cappuccinos and working on copious cross-sections to keep the machine operators exactly informed of each step of the process. All of these sketches were required to compensate for my scanty German!

With a maximum depth of 18 feet, there was a lot of material to move. For all that, the excavation proceeded with remarkable efficiency and speed, scarcely hampered by weather from which the operators seemed immune. These are hardy people, farmers and mountaineers who are never stopped by a little rain or snow. Despite onerous conditions, they worked ten- to twelve-hour days and seemed as jolly at the end as when they began.

| It was very impressive to see the array of equipment the farm had on hand in action – and just as interesting to observe how skillfully the owners and staff put it to use. The excavation moved along at a smart pace, guided by surveying equipment and my drawings, while some on staff showed their artistic flair in ‘pruning’ the deadfall oak tree for later placement beside the pond. |

It seemed unusual to me to have the clients do so much of the work themselves. Still, I was happy just to keep producing drawings as we progressed and marveled as they ran their own excavators and machinery with such skill. Call it extreme, but we carried out the entire project in short order and in a very cost-effective manner!

To maximize the reflective expanse, we decided that the pond and its filtration system should be incorporated into a single body of water. (Normally, my preference is to place filters in separate ponds at lower levels so that pollen, leaves and other flotsam can pass over a weir or waterfall to be digested by the filter’s bacteria and plants.)

The result of this decision was the insertion of a rock dividing wall that would come up to within six inches of the surface and keep any surface protrusions to the minimum. This called for rock of far larger sizes than were available in the farm’s stoneyard – at which point we discovered that, despite the property’s proximity to a mountain range, there were few big rocks to be had in the area.

| Once the digging was done, we spread geotextile across the space and then brought in huge pieces of enormously unwieldy EPDM liner for seaming. With the seaming done, we covered the liner with another layer of protective fabric, then went about setting the perimeter. In some places, we used blocks of porous tufa (top right) before moving over to prepare the biofiltration system’s manifolds and vertical separation shafts, all of which we subsequently buried under hundreds of tons of gravel. |

With some research, we learned that the five- to 12-ton pieces we needed could be found across the border in Innsbruck, Austria, so off we went. For one of the few times in my career, it mattered not at all that these specimens lacked a lovely patina of lichen and moss, as they would be mostly under water. Nevertheless, I was on the lookout for a few weathered beauties I could use to form embracing arms for the sheltered sunbathing cove.

While we were off shopping, the hard work of laying out and seaming sections of EPDM liner between protective mats of geotextile was under way, and we were soon able to start placing rocks, steps and gravel. Given the size of the pond and limited reach of the machine’s arm, we had to “paint” our way out from the center with the heavy rocks, rolling back the liners as we proceeded.

PLUMBING TO SCALE

After building the rock wall and before laying down the filter gravel, we needed to position a system of perforated pipes that would be connected into a pump house situated below the far bank of the pond. The local agricultural depot proved an excellent resource: They had every type of pipe and all the fittings we needed.

Provided the pipes are not placed too far apart, of course, almost any type of four-inch perforated PVC pipe would have done the job. But the clients, based on their experience with the farm, favored using six-inch ridged main trunk lines connected to flexible branches of four-inch perforated pipe to collect the water beneath the gravel.

Although a little more costly, this was a good idea that we enhanced by adding a few vertical separation shafts to keep gravel out of the pipes and prevent starving of the pumps by serving as overflows in the event the filter bed ever became clogged. When all was connected, we then added 200 tons of gravel in various layers to cover the pipes and raise the floor of the filtration area to within a few inches of the water’s surface. Later this space would be planted with drifts of emergent plants.

Meanwhile, large, cut blocks of tufa were being installed on part of the pond’s perimeter where we wanted to run lawn up to the water’s edge. (We also used these blocks to construct rough steps down to about five feet below the water surface.) We brought the liner up behind the blocks: This allowed the porous tufa to remain saturated and thereby allowed the grass to “drink” and stay green even in the heat of summer.

| The completed pond is a feast of reflections – of nearby trees, of the farmhouse, of the fallen oak and of aquatic plants in and around the crystalline water. |

I had completed a detailed planting plan for the clients, and while fire hoses were filling the pond from various hydrants located around the farm, we drove to a local supplier of aquatic plants to find material for placement in the biofiltration zone and in strategic places around the pond. The climate swings here are quite extreme, with hot summers and very cold winters, so we selected hardy natives and tried-and-tested cultivars.

During one pre-construction storm, a mighty oak tree had blown down in a field adjacent to the new pond. This led all of us to consider an exciting possibility: Instead of a inserting a pond-side rock from which to jump, we could use the recent windfall as a jumping tree! This proved to be a lot of fun – and greatly enhanced the general appearance and naturalism of the pond.

As part of my original design, I had also proposed a small octagonal boathouse with a deck, but it was decided to postpone this feature due to time and budgetary constraints. A suitable level platform was left a few feet beneath the surface for its later addition. In the meantime and to some extent, the verticality of the tree compensated for this omission.

A LATE TWIST

As the pond was filling and we were about to lay out the heavy rubber mats to make ready for the gravel covering that would provide the horses with safe, ready access to the pond, the mother got cold feet about swimming with horses. As she rightly pointed out, the big animals might get over-excited and run amok among the beautiful aquatic plants we’d just inserted, thereby ruining the biofilter.

I had very mixed feelings about her decision. On the one hand, it seemed a lost opportunity for equine adventures, but on the other, I feel sure the aquatic plants and filtration system issued a huge gurgle of relief.

| The pond’s crowning glory is, of course, reflections that capture images of the distant Alps – and of the towering clouds that bunch up against those craggy peaks. |

Sadly, it took so long for such a large body of water to fill up that we had to leave before witnessing the finished results. This happens all too often, with the designer leaving a site behind, perhaps forever, without seeing the plants established or the water systems fully up and running. In this case, however, I was amply encouraged by pictures sent to me of the family climbing on the jumping tree and by frequent reports of swimming and frolicking – minus horses.

As they put it, the pond has completely changed the atmosphere of the farm: Now, after a long hot day of haymaking in the fields, they can jump into the deliciously cool, clear water and feel all the stress of work (and the hayseeds) wash away. Isn’t it wonderful how water can enhance the quality of life?

Anthony Archer Wills is a landscape artist, master watergardener and author based in Austerlitz, N.Y. Growing up close to a lake on his parents’ farm in southern England, he was raised with a deep appreciation for water and nature – a respect he developed further at Summerfield’s boarding school, a campus abundant in springs, streams and ponds. He began his own aquatic nursery and pond-construction business in the early 1960s, work that resulted in the development of new approaches to the construction of ponds and streams using concrete and flexible liners. The Agricultural Training Board and British Association of Landscape Industries subsequently invited him to train landscape companies in techniques that are now included in textbooks and used throughout the world. Archer-Wills tackles projects worldwide and has taught regularly at Chelsea Physic Garden, Inchbald School of Design, Plumpton College and Kew Gardens. He has also lectured at the New York Botanical Garden and at the universities of Miami, Cambridge, York and Durham as well as for the Association of Professional Landscape Designers, from which he received the 2013 Award of Distinction. He is also a 2008 recipient of The Joseph McCloskey Prize for Outstanding Achievement in the Art & Craft of Watershaping.