Making Edges Vanish

There are two common options when it’s time to design the wall for a vanishing-edge swimming pool: cut it in or cut it away.

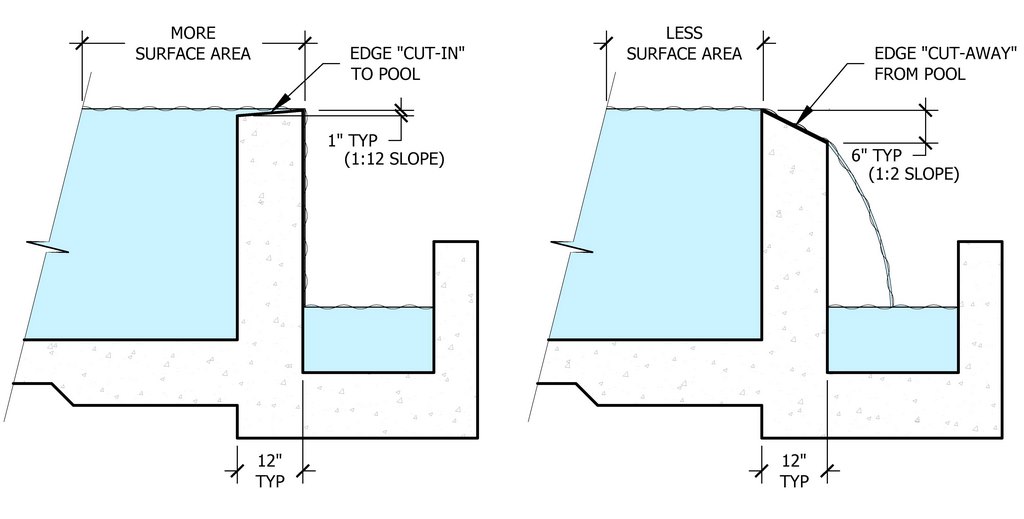

With a cut-in approach, the top of the wall is cut down into the pool so that the water surface extends to the outside edge of the wall – effectively submerging it even when the water is not flowing over the edge. By contrast, a cut-away wall is one where the top of the wall angles down and away from the pool so that the water surface terminates at the inside edge of the wall. This results in the top surface of the wall staying dry when the water is not flowing over the edge.

Through the years, we at Watershape Consulting (Solana Beach, Calif.) have reviewed numerous design concepts from architects, landscape architects and pool builders who want our help with structural and/or hydraulic design. In that time, we’ve noticed that the pool builders tend to gravitate toward the cut-away option, while the rest are more inclined to use the cut-in detail.

The pool builders may be arriving at their decision by accident or habit, but I’m convinced that the architects and landscape architects, trained in design and attuned to visual effects, are making a conscious decision to maintain the crisp line presented when the water rolls over a sharp, 90-degree edge and flows straight down the wall.

It’s a key choice: When we’re asked for advice, we almost always side with the architects and landscape architects and recommend the cut-in approach.

WORKING THE ILLUSION

Given the fact that pool builders design the great majority of vanishing-edge watershapes, many more edges are being cut away than are being cut in. The often-stated reason to cut away the edge is to eliminate the intrusive appearance of the submerged wall-top section found with a cut-in approach. Cutting away, these builders say, creates their preferred illusion that the edge of the vessel is paper thin or even non-existent.

| This is a simplified cross-section of a vanishing-edge pool showing the difference between a wall that’s cut in (left) and one that’s cut away (right). While these may be seen as common profiles, there are an infinite number of other options when it comes to geometry and dimensions. |

For the right pool configuration in an ideal location, these cut-away designs are certainly visually dramatic. Frequently, however, the approach is misapplied, mostly by those who fail to evaluate how the edge will look using all available lines of sight. If the top of the wall can be seen from any angle anywhere on site, it will become a distinct visual intrusion at least part of the time and is therefore the wrong aesthetic choice for the project.

| In this project, the pool edge and the cascading edges of the catch basins are all cut-in, making for sharp 90-degree angles that mirror the sharp 90-degree angles of the Frank Lloyd Wright-inspired house looming above. Imagine that if these edges were cut away: The chamfer would eject the water away from the vertical walls and the detail would not coordinate with the house at all. (Project by Bill Drakeley, Drakeley Pool Co., Bethlehem, Conn.) |

These pool builders may be operating under the assumption that, by avoiding an inside edge, they are strengthening the thin- or no-wall illusion. What they fail to consider is that, if a cut-in edge is kept fairly flat, refraction works in such a way that the submerged wall section won’t be seen.

All of this explains why, whenever we at Watershape Consulting are asked, we almost always suggest going with cut-in vanishing-edge walls. And we do so because we know that the top surfaces of the cut-away walls appearing on most of the vanishing-edge pools designed by pool builders are visible from somewhere. If it’s not from the deck or the living room, it’s from another room or, very often, from a balcony above deck level. Seen from these perspectives, the cut-away look fails as an illusion, fails as an aesthetic asset and simply shouldn’t be used.

A vanishing edge is meant to make a bold architectural statement. If there’s a giant, visible chamfer on the edge, it weakens that presentation and degrades the sharpness for which the vanishing edge of water is most valued – and that’s before you consider what happens to the water as it rolls down the cut-away face. Here, momentum effectively launches the water off the lower edge and out into the air, causing unnecessary evaporative water loss, excessive water cooling and, often, undesired noise.

A vanishing edge is meant to make a bold architectural statement. If there’s a giant, visible chamfer on the edge, it weakens that presentation and degrades the sharpness for which the vanishing edge of water is most valued – and that’s before you consider what happens to the water as it rolls down the cut-away face. Here, momentum effectively launches the water off the lower edge and out into the air, causing unnecessary evaporative water loss, excessive water cooling and, often, undesired noise.

| Some designers would have tried to hide the top surface of the vanishing edge walls by cutting them away instead of submerging them as was done here. We did so because we believed the robust appearance of the structure itself would harmonize with the bold details of the coping and the house. The water surface is also larger because of this choice, and the water does not leap off the wall and overshoot the catch basin, which is five feet below the edge. (Project designed by Ground Studio, Monterey, Calif.; engineered by Watershape Consulting, Solana Beach, Calif.; and built by Paradise Pools & Gardens, Campbell, Calif.) |

These hydraulic-jump effects may be desired in some projects where the wall view doubles as a waterfeature – as in cases where the edge is turned around to face the deck and the home’s prime viewpoints or when a lower deck area is placed beyond the wall. In these cases, however, the flow rate almost always has to be kicked up considerably (and inefficiently) to achieve the right sort of downstream or waterfall effect.

GO WITH THE FLOW

Those professionals who design vanishing-edge pools with cut-in details also tend to be aware of something of great visual importance: They understand that they don’t need to hide the wall with an illusion. In fact, they know that the presence of the wall is expected, indicates strength and builds confidence even when it can’t easily be seen.

| This is an appropriate application of a cut-away detail. Here, the vanishing edge pool has a cut-away edge that ejects water over a wall made with rough, natural stone. That wall is curved out and away from the primary view of the house, so nobody ever sees its top from the house. Indeed, the main effect is seen from below, with the water jumping away from the wall to create visual drama as it falls into a catch basin wide enough to capture the flow. (Project built by Baker Pool Construction, Chesterfield, Mo.) |

We’ve known more than a few clients who’ve told us that they don’t like vanishing edges because they “don’t feel secure.” They have the sense, however irrational it may be, that the paper-thin wall might simply fall away. This creates tension when they should be feeling relaxed in buoyant bliss. Conversely, these users are reassured to know there’s a thick, secure cut-in wall there and even regard it as an invitation to rest their arms atop it as they enjoy the view out across the edge.

| This project was the subject of a construction-defect suit because the pool had shifted and rotated down the hill. Seen here from the primary viewpoint of the house and patio, the cut-away wall is on clear display. (As I see it, the view would have been much improved had the wall been cut in: If I can see the wall, I want water covering it!) A larger issue here is that the cut-away chamfer caused the water to jump over the small, shallow gutter, which helped erode the hillside and likely contributed to the differential-settlement issue. |

In our projects, we augment that sense of heft by making our walls at least 12 inches thick – and that’s before any veneer or finish is applied. For a cut-in detail, the inside top of the wall is angled to drop no more than a half-inch or an inch below the level of the outside wall. This eliminates any hydraulic-jump issues, and there’s also an important visual plus: By keeping the angle soft and using appropriate finishes, the top of the wall becomes essentially invisible because there is more reflection and less refraction.

| Here, the wall is cut in beneath the water’s surface, and you can’t see it at all from this prime viewpoint because there is 100-percent reflection and zero-percent refraction and the wall disappears. In addition, cutting the wall away here would have required a larger catch basin and would have made the top of the wall visible to anyone seated near the end of the deck. (Project designed by Skip Phillips, Escondido, Calif.); engineered and built by Watershape Consulting) |

The soft angles we prefer are easy to achieve with tile and polished granite. If the finish of choice is a rough natural stone, there may be a need for a slightly steeper angle – but only within equally slight limits!

|

Flat Truths It’s possible to use a perfectly level wall top for a vanishing-edge pool, but it seldom happens for a couple good reasons. First, when the water is not flowing, the top of the wall will be visually obvious. Second, if unbroken reflections off the surface are a primary motivation in wanting a vanishing edge, it makes no sense to interrupt that reflection with a band of dry tile or stone when the system is off. It is better to cut in the edge and let the reflecting water surface extend over the wall. A level wall also invites serious hydraulic jump, which happens when the slow-moving volume of water reaches the edge of the wall and suddenly races over it. The water actually juts out beyond the plane of the wall by up to a quarter of an inch, and it does so with enough departing turbulence that it disrupts the reflective surface it’s leaving behind. As is suggested in the accompanying text, the easiest fix is simply lowering the inside edge of the wall – that is, cutting it in and dropping it down below the outside edge by at least a quarter inch. Problems solved! — D.P. |

Regardless of the exact slope of a cut-in edge, the basic hydraulic effect is the same: The water surface extends to the outside of the wall, submerging it and making the pool look larger. Moreover, with tight edge tolerances, the wall will operate at low flow rates, with the water rolling over the edge and flowing down the outside of the wall into the catch basin without breaking past the plane of the wall. The effect is quiet, calming and efficient.

At the end of the day, of course, every project needs to be assessed on a case-by-case basis. The cut-in/cut-away decision is just one part (however important) of edge-detail development, followed by materials selection, tectonic decisions and myriad options that affect both aesthetics and hydraulic performance.

Bottom line: We don’t think you can ever go wrong with a cut-in detail, but you certainly can disfigure an otherwise beautiful watershape by using the cut-away detail when it’s not appropriate. Why risk it?

Dave Peterson is president of Watershape Consulting of San Diego, Calif., and a co-founder of Watershape University, an educational service for designers and builders who work with water as a creative medium. He’s been part of the watershaping industry since 1994, starting his own firm in 2004 after stints with an aquatic-engineering firm and a manufacturer. A registered civil engineer, he now supports other watershape professionals worldwide with design, engineering and construction-management services and may be reached via his web site, www.watershapeconsulting.com.