Pigments and Pools

There are few things prettier than the classic sky blue that results from the combination of white plaster and clear water. In recent times, however, amazing and even startling colors and color combinations are appearing within swimming pools and other watershapes courtesy of either integrally colored plaster, white plaster paste coupled with colored aggregate or colored paste with a colored aggregate.

Various textures are also available courtesy of these finishes, with surfaces ranging from the traditional, slightly rough feel to bumpy aggregates or a perfectly smooth luster.

Whatever the option, producing these fantastic visual and tactile results requires thought, skill and proper execution. Application technique is crucial if discoloration or splotchy results are to be avoided, for example, and using chloride accelerators is ill advised. But in most discussions of the subject of colored pools, too little attention is paid to a third key factor: Not all pigments are created equal – and not all of them are compatible with oxidized (that is, chlorinated, brominated or ozone-treated) environments.

FADING GLORY

When it comes to colorfastness – that is, the ability of a material to retain its initial color over time – there are two primary classes of pigments to consider: organic and inorganic.

Organic pigments are generally carbon-based and usually contain hydrogen as well. They are also generally associated with something that once was alive, whether a plant or animal. By contrast, inorganic pigments are typically derived from metals and non-carbon-based materials. The key relevant distinction between the two is that, in watershape environments, inorganic pigments will hold their color, while organic compounds will whiten or lose color over time in the presence of sufficient levels of an oxidizer.

There’s another factor that needs mentioning: Beyond the bleaching issue, the simple fact is that inorganic pigments generally cost significantly more than their organic counterparts. So while organic pigments can produce vivid, brilliant colors and are much lower in cost, they are unlikely to hold onto that brilliance for any significant duration.

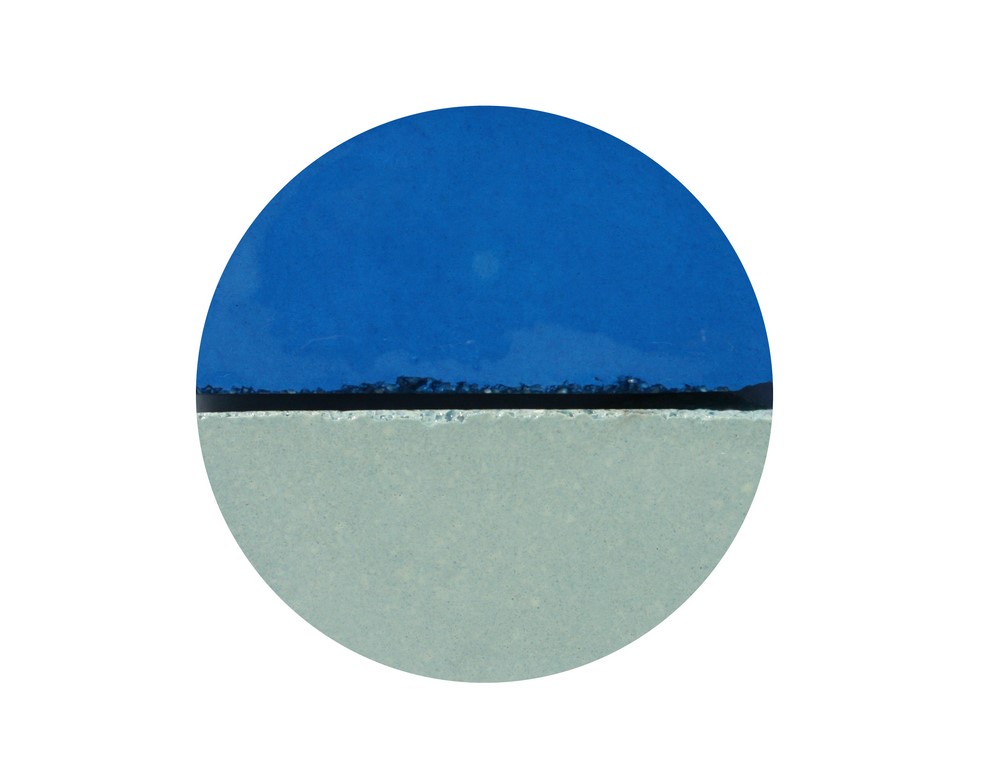

| This is a case in which an organic blue dye was used in a pool treated with an oxidizer that ultimately caused the color to fade. This chunk was collected when the failed finish was chipped out and replaced. |

We at onBalance, a consulting firm involved in research on the relationships between water chemistry and pool plaster surfaces, have studied and compared these materials as part of our ongoing mission to explore issues that can arise in the long-term performance of pool plaster. Through forensic analysis of unsightly faded and blotched pools as well as laboratory research and examination of the scientific literature on cement, plaster and aggregates, we have come to the conclusion that the organic class of pigments should be avoided for any surface that can be expected to come into contact with water treated with an oxidizer.

Indeed, our research shows that oxidizers are primary factors when it comes to the fading of plaster colored with organic pigments. (Our focus is on swimming pools and spas, but these observations hold true in any watershape where an oxidizer is present.)

Although any oxidizer may cause a loss of color in an organically-pigmented plaster surface, chlorine is, of course, the most common oxidizer used for controlling algae and pathogens. The actual level of chlorine required to bleach organically pigmented plaster varies depending on the specific coloring agent. Some organic pigments, for example, may resist discoloration in the presence of chlorine at the levels recommended for normal pool maintenance – that is, in the range of one to four parts per million – while others may not.

|

But the problem is, certain accepted maintenance practices can dramatically raise (even if only temporarily) the level of chlorine in the water immediately against the plaster. For instance, in the periodic shocking or superchlorinating of a swimming pool, levels of sodium hypochlorite (bleach) or calcium hypochlorite (granular chlorine or shock) may be added in such a way that local areas of the pool water may reach much higher levels.

In addition, when treating water in which there’s a suspected outbreak of cryptosporidium or giardia, the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) recommend levels of chlorine as high as 20 parts per million to be maintained for a 24-hour period. Since even lower levels of chlorine may bleach organically pigmented plaster, these remedial practices may cause quicker fading.

MAKING IT STICK

The point here is that the chemical applicator coming on site months or even years after a pool is completed has no way of knowing if the pigment is colorfast to bleaching. As a result, the general assumption will be that it is colorfast – a supposition that can result in a permanently blotchy, bleached surface.

This won’t happen every time, but these problems arise often enough to cause general alarm. And this is despite the fact that these problems can be completely avoided if the designer specifies and the builder insists on using a pigment that is known to be compatible with pool/spa environments.

And this is true for all watershapes, even those that start their working lives without chlorine being part of the package. There’s no way to anticipate what will happen when the home changes hands or when it comes time, years in the future, to change out the equipment and make new decisions about how the water will be treated, or when that fountain or other waterfeature accidently becomes a swamp that requires heavy remedial chlorination.

So here are our recommendations – a ten-point how-to list for using pigments in pool environments:

[ ] When a watershape is to feature colored plaster, exclusively specify inorganic color pigments. [ ] Think in terms of blacks, grays, browns and other colors: Blue pigments seem to be more problematic than the other possibilities.|

Ongoing Studies To explore some of the key issues related to colored plaster, onBalance will soon be finishing a demonstration pool with sections colored in various organic and inorganic pigments. These sections will then be maintained in both balanced and aggressive water. Results will be forthcoming and will be shared as they become available. — Q.H. |

A SIMPLE TEST

To be sure, there are some exceptions to watch for when specifying pigments. Just having the word “copper” in its name does not, for instance, mean the pigment is inorganic. The popular “copper phthalo blue” is commonly used by some pigment manufacturers, for example, but it is actually organic and readily bleaches. (The only blue pigments we have tested and found to be suitable for use in oxidizer-treated watershapes are cobalt-based.)

On the flip side, having the word “carbon” in the pigment’s name does not always mean it is organic. “Carbon black” is carbon-based, but it has already been oxidized – meaning no further bleaching should occur with exposure to chlorine. (But this does not mean that carbon black is acceptable in a pool environment: According to pigment manufacturers, it does not bond in the paste matrix the way that iron oxide does; as a result, carbon black can be drawn out of the paste with time, resulting in fading.)

| These are plaster coupons we made and cut in half to test various pigments. The two on the left were made with inorganic black (left) and inorganic blue (middle left) pigments and proved to be colorfast. The third was made with an organic blue material that faded dramatically when exposed to an oxidizer (middle right). The fourth is a case where organically pigmented black and blue aggregate faded or lost all color once exposed to an oxidizer (right). |

We’ve also run into pigments where the material is a blend of inorganic and organic agents – and there are cases where, because of the way things are packaged and described, it’s more or less impossible to know with certainty whether a material is of one form or the other. This is why we have a final recommendation: If in doubt (and even if you are fairly certain of what you’re getting into), why not make up a trial batch and test it?

In our own research, we make plaster “coupons” by combining one part colored cement with one-and-a-half parts aggregate (or sand) and a half part of water (all measurements by weight). We then cut the coupons in half, holding one in reserve while the other is submerged in full-strength swimming pool bleach overnight.

When the two halves are compared the following day, it’s usually obvious which samples are colorfast in the presence of bleach and which are not. If you want, you can use bleach at lower concentrations, but the testing will require more time. That’s why we recommend “crash testing”: It’s a quick, easy way to figure out if your clients will be happy or disappointed in the long run.

A plasterer we know says that people who pay a premium for an upgraded surface also have higher expectations when it comes to the results. For us, those higher expectations can be met or exceeded by a combination of the proper materials, careful workmanship and subsequent routine maintenance.

The stakes are higher when colored plaster is used, but the basic principles are still the same: If you want a happy client, know what you’re using and why.

Que Hales is vice president and general manager of the Tucson, Ariz., branch of Pool Chlor, a service company, and has been active in the pool industry since 1980. Doug Latta is President of Aqua Clear Pools, a service/construction company based in Los Angeles since 1975. Kim Skinner began his work in the pool industry more than 50 years ago and is now president of Pool Chlor and its offices throughout the Southwest. The three are partners in onBalance, a consulting firm that performs both laboratory and field research on pool-water chemistry and on the relationships between water chemistry and pool plaster surfaces. For more information, visit www.poolhelp.com.