Working on the Road

Working on a large-scale project is a challenge when it happens even ten miles from your home base: Big jobs are just plain tough. But building that same project 150 miles away? That takes the difficulty to another level – and when you mix in an extremely difficult, environmentally sensitive site, it can feel as though you’re operating on another planet.

A case in point can be found in our participation in a design/build project on a remote cottage estate in the stunning Muskoka district of Ontario, Canada. We at Poolscape (Toronto, Ontario) were asked to take care of designing and building the watershapes, working on site alongside International Landscaping of Hornby, Ontario. That combination of contractors isn’t unusual in a project of this scope, but right from the start there were elements of communication and coordination we had to consider.

Then came my first site visit, which took place in the dead of winter. Site access came via a long, winding gravel road piled with snow ten feet high on either side. When I finally reached the job site, I soon found myself at the edge of a granite cliff looking more or less straight down 130 feet to the pristine lake below. It was a long way up from the frozen water, with a fall to be broken only by an array of native trees clinging to the cliff.

It was one of those moments when you either forge ahead – or retreat to your warm, dry truck to take a long drive home, comforting yourself with thoughts of safer, saner, more predictable projects closer to home. But I like a challenge, so I stayed on the cliff, taking a long look around me.

SETTING THE SCENE

The design portion of the project wasn’t much affected by distance. I design faraway projects all the time, sometimes without even visiting the site. (That’s not my preference, of course, but in a digital world it is almost becoming the “new normal.”)

| This was how the site looked when I arrived for my first visit – lots of snow and, beneath it, a huge chunk of bedrock that would have to be removed to create a space for a pool and spa alongside the cottage, which was still under construction at the time. |

The general contractor had given us a survey report on the property – but also informed us that a previous landscape contractor had completed some site alterations and that a few of the numbers had changed. So we took our own on-site measurements over snow and ice, using steel probes to find the granite bedrock below and catalog where the alterations had occurred.

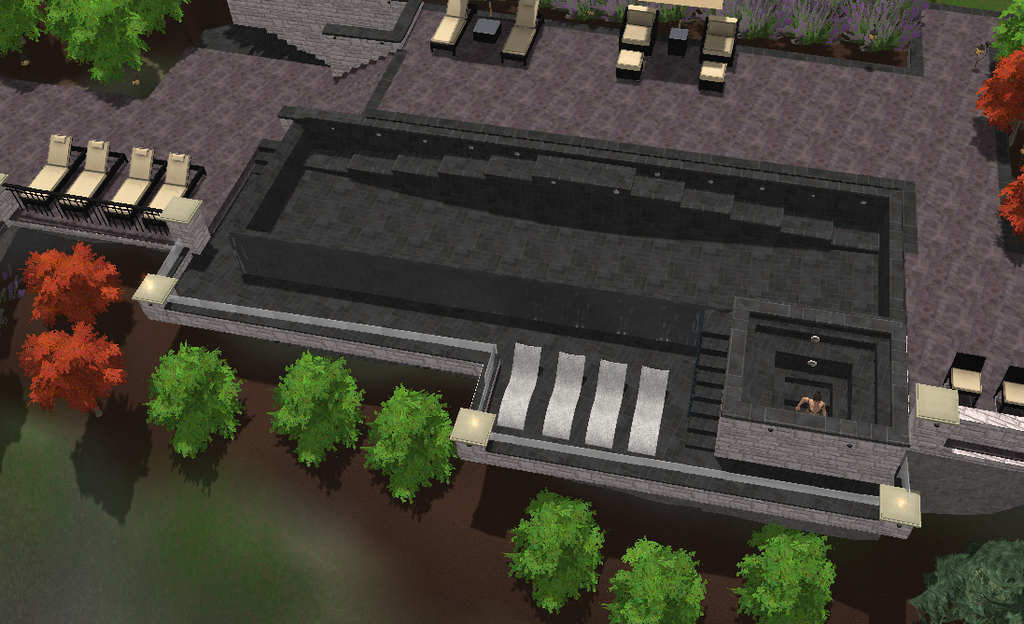

With those new measurements in hand – and a much better appreciation of the site – we proceeded into the design-development process. My preference these days is to use the Pool Studio design software (produced by Structure Studios, Henderson, Nev.) to generate initial three-dimensional drawings, mainly to give the client a clear sense of what we might do on the edge of his cliff – something quite difficult to convey to most clients with standard two-dimensional sketches – but also to assist our engineering team. Once all of the details were settled, we sent the files off to Watershape Consulting (Solana Beach, Calif.) for conversion to CAD format.

All of this, as I indicated above, was reasonably standard stuff – the kind of process we’d pursue if the project were happening around the corner from our offices. But that’s where simplicity ends: Once the construction documents came back to us, the adventures of remote contracting begin in earnest.

ALIEN TURF

It all started with permits. Obtaining them to work in a faraway location can be daunting, mainly because we all know how much easier it is to navigate the process if you have local knowledge. To sidestep many of the anticipated difficulties, we hired a planner familiar with the myriad issues that crop up with large scale projects; in addition, we valued his expertise in projects in environmentally sensitive areas in the Muskoka district.

We knew up front that this environmental clarity was going to be a key to this project’s success. The Muskoka area is a Canadian treasure – pristine lakes, untouched native forest, incredible rock formations and protected vistas in every direction – so we also knew that the local building department was likely to look askance at outsiders.

It’s not that we were building in the absolute middle of nowhere. Our work site was set among some very expensive homes the locals refer to as “cottages” – basically country estates long held by a number of legacy owners – and we knew that those who were already there would never be happy at the thought of further development in the neighborhood.

| The blasting contractor removed tons of material from the top of the slope (left, middle left), gradually creating a shelf on which we were to place the pool and spa as well as a subgrade service and entertainment area (middle right). All of this was undertaking with great care, of course, to avoid damaging the existing structures. The view from above (right) gives a clear impression of just how much of the rock had to be removed for our purposes. |

In other words, it wasn’t all about playing by environmental rules. To an equal extent, it was about appeasing the locals and letting them know what we were doing would in no way be more than a short-term hassle for the neighborhood – and that, in fact, the new cottage would be a great long-term asset.

Everything had to be detailed for the permit application – no stones unturned, no issues left to question. We offered fully engineered plans and also addressed drainage issues, garbage disposal, planting plans, long-term forest maintenance, insect management, runoff mitigation, noise and dust generation. But perhaps most important of all, we submitted a complete plan for construction parking and traffic management – incredibly valuable in pacifying the locals.

Typical of projects on this scale, it grew as we moved along. Around the poolscape, there suddenly appeared a massive, elevated sports court as well as an elaborate Ipé-and-steel lakeside dock along with an expanded planting plan and a below-grade entertainment space.

Every new addition required a permit, an amendment, hearings, lawyers, planners, drawings, structural engineering, soils engineering and more. Permits had to be obtained for construction, landscaping, HVAC, electrical, propane tanks, blasting, parking, dock construction and lakeside right of way – all of it made more complex (and costly) because all of the designers, engineers, planners and lawyers had to drive three hours each way to attend meetings.

MAKING A SHELF

With these initial rounds of permitting out of the way, we were finally able to start real work on site. Our first task involved blasting away hundreds of tons of granite bedrock to create a shelf for the pool and below-grade bunker. We used a local subcontractor for this job – again, there was great value in that company’s knowledge and specific experience.

We started our work early in the spring, which is known hereabouts as “half-load season” because less weight is allowed on truck axles in the time before the frozen ground thaws out. We had to obtain special permission to bring in the big dump trucks required to move the blasted granite just 300 yards over a public road to reach a stockpile location we’d established at one end of the property. (We later repurposed this rock to create planted retaining walls along the cliff – a recycling step that won us some points with the locals.)

The blasting (which, I might add, won us no new friends) started before we had really begun to mobilize on site. As it proceeded, I made several trips to verify that the removal was sufficient for our construction needs. When we were satisfied that we had what we needed, the subcontractor cleared away the blasting equipment and we brought in a surveyor to ensure that we had a set of extremely accurate measurements.

Now that we were ready to get going on site, accommodations became a big issue. Our onsite structural-concrete construction crew, for example, included 15 to 20 workers, depending on what was needed.

| The preliminary design drawing for the pool (left) wasn’t hugely different from the project as built – a monumental task that involved expansive forming, several truckloads of rebar (middle left) and the application of 1,200 cubic yards of poured-in-place concrete (middle right and right) – all on the edge of a 130-foot drop to the lake below. |

To put them up, we rented two cottages and arranged with a local hotel to take care of occasional overflows. We also arranged with a local gourmet restaurant to cater lunches and dinners. (The way I figure it, a construction crew is a bit like an army, and an army runs on its stomach.) We were working in a location far from our home base, but we were also locally remote – a good distance from the job site to basic services by steep, winding roads. This meant, for example, that we brought in drinking water by the skid.

Dividing into two cottages was a strategic notion: This allowed for splitting the crew into groups that have historically lived and worked together well under these remote circumstances. The absolute last thing we needed with this much pressure and this much at stake was to have conflicts brew between crew members off the job site. I also learned a long time ago that it works best if I stay away from the group-living quarters. This time, I was nearby at a bed-and-breakfast and kept a respectful distance from the crews during off hours.

We were also up against the clock: We knew that if we ran over our time budget – and into the prime cottage-renting season – that our costs for accommodations would jump by about 400 percent per week. And we did run over our time and the rates did go up for a while, but we’d allowed enough cushioning in our room and food allowances that it stung but didn’t hurt too much.

As the entire project unfolded, there were times when more than 100 tradespeople were on site daily. The locals had the advantage of going home at the end of the day, but there were lots of us in hotels and various other rentals, far from home.

STAGING THE ACTION

Above, I mentioned spring road thaw and restrictions on axle weights. With that in mind, we’d stockpiled some gravel on site when we first began our work in early spring – just before the road restrictions were in effect. But that didn’t help us when it came time to start pouring concrete a bit later on.

Here, we had to get creative. Our concrete mix had a large number of additives, and only some of them were mixed in at the batch plant. (We added a super-plasticizer and a waterproofing admix on site, while retarders and other materials were added at the plant.) Because of the road restrictions, we could only move half-loads to the site, four cubic yards at a time per truck.

To make it work, we set up a staging area off of the main asphalt road (no weight restrictions there!) where full trucks of concrete were split onto shuttle trucks that delivered to the boom-pump truck. This slowed us down and added cost and complexity, but it let us preserve the integrity of the batches delivered by the plant and allowed for mixing of additives into full-size loads – and somehow we made it work: In all, about 400 of the 1,200 cubic yards of concrete we ultimately used were delivered as spilt loads.

| One of the late additions to the project was an immense sports court set above an eight-car garage. As the drawing shows (left), it was made to fit within the overall site program by using key details borrowed from the cottage and the pool area. It also called on all of our skills in working with huge concrete structures (middle) perched on a steep slope (right) – this time without the blasting! |

Yes, we made it work, but there were some surprises. As I mentioned, we used a waterproofing admixture. After much discussion between the local concrete supplier, our engineers and the waterproofing supplier, the first 80 yards were delivered and pumped on site.

I reached the top of the cliff early the next morning and was shocked to see that the concrete had not set in the forms. Talk about a slow cure: The waterproofing agent acts as a retarder, but the concrete batcher had inadvertently added the usual amount of retarder to the mix, as the batch plant was an hour’s drive from the site. After a flurry of phone calls, the owner of the concrete company arrived with a thermal gun and confirmed that the concrete was curing and would set — eventually.

We stripped the forms the next day and everything turned out fine. But this was far from the end of the adventures we had on that cliff in Muskoka. In the concluding Part Two of this article, we’ll delve into a range of issues that came up in the course of our work on site and round out the set of lessons to be learned about working remotely in an environmentally sensitive area – with touchy neighbors thrown in for good measure.

Barry Justus is president of Poolscape, the international-award-winning design/build firm he founded in Toronto, Ontario, Canada, in 1991, and principal at Justus International Consulting. A graduate of the University of Western Ontario, he has written more than 40 articles on pool design and construction for a variety of magazines. He is also an instructor for Genesis 3 and is a member of the Society of Watershape Designers. He may be reached at barry@poolscape.com.