Keeping Pests at Bay

Integrated pest management – or IPM, as it has become widely known — is a concept that emerged about 20 years ago when landscape professionals and others involved in the management of plants and the land began incorporating its techniques into their landscape installation and management projects.

Unfortunately, however, the concept of pest management is all too often seen as the exclusive province of those engaged in landscape maintenance: As a rule, designers and design/build contractors rarely pay more than lip service to pests in general and give even less attention to considering them as part of an integrated approach.

At the risk of being labeled a “tree hugger,” I believe it’s time for everyone involved in the various landscape professions to embrace IPM. The simple truth is that, as landshapers, we need to pick up on the lessons of our collective experience. As the saying goes, those who fail to learn from history are doomed to repeat it – as we have, over and over again.

HISTORY LESSONS

Of course, we can’t embrace what we don’t understand, so a brief history lesson is in order. To begin with, as the people of the United States built their villages and towns, cut roads across the landscape and established new communities across this broad land, our forebears chose the American Elm (Ulmus americana) as the ideal street tree. So ideal, in fact, that we planted them up and down virtually every Main Street east of the Mississippi.

The Elms were planted at intervals of 20 to 25 feet on center, with their vase shapes arching gracefully and joining over the roads in majestic and comforting ways. Many of you know the story: By the mid-1900s, the Elm Bark Beetle had arrived on our shores and had begun spreading the dreaded Dutch Elm Disease. And when the beetle missed a tree, naturally occurring root grafts between closely planted trees helped the disease to spread.

Today it’s rare to find an American Elm that has escaped the devastating effects of Dutch Elm Disease. Research is ongoing to find resistant cultivars of Ulmus americana and some are showing promise, but the damage was done long ago.

| Norway Maples (left) were commonly planted as replacements for disease-devastated American Elms – a beautiful but poor choice. These are invasive plants whose seeds take root anywhere within easy drifting distance of a parent tree (middle left and middle right). Moreover, their use as common street trees makes them subject to the brutishness of utility-related topping (right), a shearing that weakens the trees and reduces their resistance to invasion by opportunists such as Asian Longhorn Beetles. |

As a result of the carnage, we needed to replace the dying Elms. When the time came to select a new tree, the Norway Maple (Acer platanoides) was often the choice. It was tall, had few pest problems and grew vigorously. Unfortunately, it has also proved to be a massively invasive plant, as anyone who spends time in suburbia knows.

The tree is in fact a prolific producer of viable seeds, and the offspring of a single Norway Maple can be found in the yards of everyone within a half-mile radius of the original specimen. Moreover, on both the east coast and in the upper midwest, the Asian Longhorn Beetle has arrived, and these maples are their preferred food source. With so many Norway Maples around, the beetles have had an easy time of it and can practically walk from tree to tree.

While the effect on the Norway Maples used as street trees has been devastating, perhaps even worse is that these beetles are also attacking more preferred and economically important maple species including the Sugar Maple (Acer saccharum). In Mid-Atlantic and New England states, these trees are valued not only for the production of maple syrup but also for their fall color. Fall foliage trips are a significant component of tourism in these states, and the loss of Sugar Maples could severely affect the regional economy.

FALSE STARTS

If Norway Maple wasn’t the tree selected to replace American Elms in specific municipalities, then the Thornless Honeylocust (Gleditsia triacanthos inermis) was often the tree of choice. As with both the American Elm and the Norway Maple, the Locust was planted at 20 to 25 foot intervals on center up and down prime city streets. In this case, the webworm invaded, finding the closely spaced and uniform plantings easy pickings.

When all else failed, we turned to the Bradford Pear (Pyrus calleryana ‘Bradfordi’), and again we lined our streets with this spring-blooming, medium-sized tree. Unfortunately, however, some of these trees are subject to splitting because of the narrow crotch angle of the main limbs, while others are susceptible to graft failure and fall over, with the trunk breaking at the soil line.

Another poor choice—once upon a time in the recent past urban planters fell in love with the Russian Olive (Eleagnus angustifolia) – and what’s not to love? The plant produces fragrant flowers in early summer, has silvery-green foliage, produces silvery-tinged fruit and attracts birds. It grows quickly and has (so far) no pest or disease problems.

| Thornless Honeylocust (left) was another popular ‘successor’ to the American Elm, and it, too, has been subject to pest-related problems – in this case falling victim to a webworm infestation (middle). In this specific tree, the webworms eventually killed the lower branches, which were pruned away (right). |

Anyone who has experienced a long-term relationship with this plant, however, quickly falls out of love. Once you have one Russian Olive, you will have a hundred popping up everywhere. Those birds might be forgiven for making an unholy mess as a result of ingesting the trees’ fruit, but in doing so they also (and unforgivably) do a great job of disseminating seeds throughout the landscape. (This tree is now on the Invasive Plant List for good reason.)

All of this history has one thing in common: We humans created monocultures – dominant plantings of just one species – that facilitated the spread of disease and insect problems or, in the case of the Russian Olive, a plant problem. And there is also the fact in a couple of these scenarios that we overused non-native species.

Does this have anything to do with Integrated Pest Management? Yes it does, because the selection of plants is Step One in any well-designed IPM program. So let’s take a look at a typical IPM program to see how a broad-based approach that can (and should) be adopted by all landshapers in the “pipeline” of a landscape’s development could prevent additional repetitions of our unfortunate history.

PREVENTIVE PLANNING

I would suggest, as you review the Integrated Pest Management program described here, that you find the step in the process that suits you: If you are a designer, for example, then you will need to start at the beginning, while a landscape installer can step into the program later on and the landscape maintainer can pick up and implement the final steps in the process.

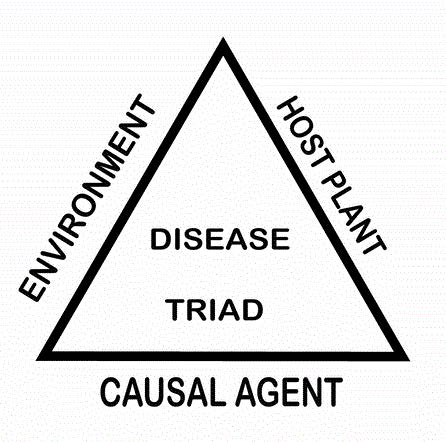

Before beginning discussion of a plan, however, it will be useful to understand just how problems arise to become, well, problems. This means you need to understand the Disease Triad (see the graphic below).

In this case, we are loosely defining a disease as any unhealthy condition in a plant. In order for said plant to be attacked by an organism (insect or disease), three components must be in place: There must be a suitable host (that is, a plant susceptible to the problem), a pest (an insect or disease-causing organism) and an environment in which the pest will thrive.

If we change or remove any single component of this triad, we significantly reduce the incidence of pest problems.

This three-part understanding can even be extended to abiotic or non-living causes. Living organisms such as insects, fungi, bacteria, and viruses are defined as biotic, while causal agents such as poor drainage and improper pruning are defined as abiotic.

Scientific studies show that plants in a weakened state are more susceptible to attack by biotic organisms. A plant that thrives in dry conditions but is planted in a poorly drained soil will not thrive and may succumb to a root-rot organism. In this example, the cause of death may be fungus-caused root decay, but the true, primary cause is the poorly drained soil exacerbated by selection of a plant that prefers dry conditions. Thus, the fungus was merely opportunistic: The environment and the plant were the major sources of the problem.

With this general understanding of the opportunities we have to disrupt the Disease Triad in mind, let’s begin a closer discussion of an Integrated Pest Management Plan, starting where many of our design projects begin – that is, with the design professional.

FIRST STEPS

During the earliest part of IPM plan development, a site analysis should be conducted. Applying IPM principles at this stage, we should include the following:

[ ] Identify existing natural vegetation: Most native species can serve as indicators for soil and microclimate conditions. If the site is devoid of native vegetation, examine areas close by to get at least some indication of conditions in the area.

[ ] Soil analysis: Conduct a thorough soil analysis, preferably taking samples of both top- and subsoil to root-zone depth and focusing on areas that differ from surrounding sites. These areas may be locations in which the topography changes from level to sloping or where the native vegetation changes, as either one might indicate a potential change in soil conditions.

| Another common street tree is the Bradford Pear, a spring-blooming, medium-sized and seemingly appropriate choice (left). Unfortunately, this tree’s narrow crotch angle (middle) makes it susceptible to splitting and branch breakage, and some are inclined to graft failure that makes them break at the soil line. In the case of the Bradford Pear planted too close to a building (right), it’s a classic case of putting the wrong plant in the wrong place. |

Note the locations of the samples on a sketch or plot plan, label them and have them tested for pH and nutrient levels. For the most part, the pH for plants and the nutrient supply will be adequate in most soils; in some parts of the country, however, soil pH can be the root of plant-health problems, as pH controls the availability of many nutrients.

Also, if you are working in an area where it’s common for the builder to bring in topsoil, it may be useful to know its source. At the risk of diverging too much, a “sugar-coating” of three inches of topsoil is virtually useless to your plants because the roots of all but annuals and some ground covers will quickly grow through this layer. If the native topsoil on a site is very shallow, it may be preferable to improve the existing soil rather than coat it with an inadequate depth of imported soil.

During the design process, use the information you’ve gathered and apply it in making decisions about plant selection (and perhaps also when recommending grade changes). Often, the information about soils won’t alter your selection of plants, but it may prove invaluable when it changes the recommendations you make to clients or installers.

SMOOTH TRANSITIONS

When you’ve made your selections, you should consider including a Plant Information Packet as a means of helping clients ensure the health and integrity of your design for years to come. Many software programs make this a simple process – one your clients will likely appreciate and for which most will be willing to pay.

Certainly, I would recommend focusing on the selection of pest- and disease-resistant species and cultivars. The concept of “resistance” versus “susceptibility” simply means that, when choosing plants known to be resistant to insect or disease attack, you increase the odds of that plant avoiding attack. It’s not an absolute guarantee, but it does help improve the odds that the plants you select will thrive.

Remember that healthy plants are more likely to be bypassed by disease-causing organisms and insects – this being the first goal of any Integrated Pest Management program.

Once the design is completed and sold, the installation contractor (or an installation crew) enters the process. The installation of plant material really begins with the acquisition of quality, healthy plants from reputable suppliers. The emphasis should be on acquiring plants that are well formed and exhibit growth typical for the species with healthy foliage, stems and roots. (The American Standard for Nursery Stock developed by the American Nursery and Landscape Association is a good reference (see https://www.anla.org/publications/index.cfm?).

During installation, the best way to be sure that healthy plants stay healthy is to give their roots the best possible growing environment. The following techniques for planting can help:

* Dig a hole at least two times the width of the root ball. The old adage of a $20 hole for a $5 plant still applies.

* Backfill with as much of the natural soil as is reasonable. You want to avoid creating a situation in which the soil in the hole is dramatically better and different from the soil outside the excavated area. If the difference is too great, you may find that the roots grow beyond the hole only slowly – or not at all.

* Be sure to plant at the same depth or slightly shallower than the depth at which the plant was grown in the nursery. Planting too deep is a major cause of plant failure, and this can be a particular problem with large, heavy trees and shrubs. Often, an over-excavated hole backfilled inadequately before placing the plant results in settling that positions a plant too deep in the hole.

| One of the keys to integrated pest management is regular examination of plants to see if they are stressed or have fallen victim to pests or diseases. In the case of Pieris, for example, it’s easy to spot the difference between a healthy, thriving plant (left) and one that has been attacked by Lacebugs (right). |

* If the tree or shrub comes in a wire basket, use wire snips to cut away as much of the basket as possible after placing the plant in the hole.

* Remove all twine from around the trunk and crown area. I was once called out to examine a Blue Spruce (Picea pungens ‘Glauca’) that had been planted about 15 years earlier and had suddenly begun to decline. To the dismay of the client, I discovered that the twine had never been removed from the base of the trunk, had not decomposed at all and was now severely girdling the tree.

* It’s also safe, once the plant is in the hole, to cut away most of the twine and to remove or roll down as much of the burlap as you can without damaging the roots.

There are a few other key indicators:

* While digging the holes for plant installation, for example, visually examine the soil’s profile. Are there signs of “mottling” (a grayish discoloration) at some depth? This would indicate the presence of standing water for at least part of the year and will be obvious even if you are in the middle of a drought.

* Pockets of organic matter or construction debris may point to disease potential. I once discovered a cache of buried concrete (probably left over from masonry work) near a foundation area. The resulting high pH caused by the leaching of water through this area had resulted in interveinal chlorosis on broadleaf evergreens in the foundation planting.

* Look for any unusual layers in the soil as digging moves forward. These may indicate poor drainage or an earlier excavation that might have an influence on the success of your new planting.

Discoveries of soil problems are always better before the project is finished and the plants have begun to suffer. It’s almost always possible to correct underlying problems during installation, which also means that it would be advisable for the installer to include an “underground problem” clause in the installation contract (although discussion of contracts is a subject for another article all by itself).

Keep in mind that all these recommendations have the common goal of creating the best environment for the plants and ensuring that at least one side of the disease triad is thwarted.

PROPER MAINTENANCE

Once the installation is complete (and every design professional should recognize, accept and appreciate this point), the maintenance contractor is truly the key to long-term success of the project. In fact, all landscape-maintenance contractors should begin to see themselves as “landscape managers” who offer much more than just lawn-care services to their clients.

With that in mind, I’d propose that every landscape manager should develop (and charge for) an Integrated Pest Management plan that includes the following:

[ ] An initial, comprehensive assessment of the identity and health of all landscape plants, including the lawn. This should also include soil testing if current information about the soil is not available.

[ ] Regular, scheduled scouting of the landscape by a crew member trained to identify pests and recognize subtle changes in plant appearance that may signal the onset of a problem. The scouting should be done at least once a month during the growing season – and more frequently for intensively planted sites or during times of potential stress.

[ ] A plan of response including reference to “threshold levels.” Thresholds are those points when a pest problem becomes serious enough to warrant control and may vary from plant to plant or even from landscape to landscape. A homeowner may be willing, for instance, to tolerate an occasional chewed leaf in exchange for a reduction in the use of pesticides, while a prominent commercial site may require absolute, ongoing perfection in the appearance of every plant.

| The aim of a good program of integrated pest management is simple and direct: It helps properly planted trees thrive in appropriate environments with reasonable care (left); at the same time, it speeds identification and treatment of trees in need (right). |

An important component of Integrated Pest Management is the idea that you avoid a knee-jerk response to the presence of a pest. Instead, when a pest appears, you develop a measured response appropriate to the size of the problem, selecting from among all tools at your disposal. In areas where crabgrass or other annual weeds are a problem, for example, it’s common to apply a pre-emergent herbicide before the weed seeds germinate. If, later in the season, a scouting visit reveals the presence of a small number of weeds, hand pulling may be the most effective method of control.

If all landscape professionals approached their part of the project with sensitivity toward pest management issues, many of the problems we see might never occur. Proper plant selection and installation combined with proper management throughout the life of a landscape are the best ways to reduce problems, maintain design integrity and establish an overall healthier environment.

Jan-Marie Traynor earned a Bachelor’s Degree in Natural Resource Management from Cook College of Rutgers University and a Master’s in Education from Rutgers University’s Graduate School of Education. She began her academic career at the County College of Morris in 1981, joining the Agricultural Technology Program, and currently serves as Chairperson for the Landscape & Horticultural Technology Department. She is vice president for the New Jersey Agricultural Education Advisory Council; an associate member of the New Jersey Nursery & Landscape Association; and is recognized as a Certified Nursery Landscape Professional in New Jersey as well as several other professional associations including the Association of Professional Landscape Designers. Traynor has presented talks and workshops at regional and national APLD meetings on a range of topics and is also a regular contributing writer for several landscape trade magazines and for Gardener News, a monthly gardening newspaper published in New Jesrey. She may be reached at [email protected].