Embracing Technology

For many years, I sat on the sidelines and watched others learn to use CAD to their professional advantage.

I’m a fine artist by background and training and have always had great confidence in my ability to draw freehand. But I also yearned to become proficient with computers because I was convinced they’d streamline my work, offer me additional tools that would facilitate expansion of my business and, overall, make me a better landscape architect. I was completely sold – but also a fish out of water.

I’d always drawn everything by hand and was very pleased with the results, as my clients seemed to as well. I was also keenly and increasingly aware, however, of how much time this process was consuming. All around me, I observed not only that others were saving lots of time by using computers, but also that the technology had sped up the pace of the rest of the world so dramatically in the past ten or fifteen years that I was in danger of falling hopelessly behind.

I had to make a decision either to climb aboard – or be left at the station. My decision was finally forced by the recognition that being a “creative type” didn’t give me the luxury of running my business in the same way or at the same pace I had even five years ago.

It was time to learn CAD – so learn it I did.

THE BIG PUSH

My initial motivation to learn CAD stemmed from the fact that I was well aware that the industry was moving headlong in its direction. Indeed, people now entering the landscape architectural profession are expected to be fully CAD-proficient, and most of the entry-level positions I know of require CAD training.

For those of us who have long-established practices, however, incorporating CAD into our work comes with a giant set of hurdles that aren’t easily overcome. I attended landscape architecture school in the 1970s, a time when relevant design software didn’t exist at all and computers (such as they were) hadn’t taken over the way they have since.

I didn’t touch a computer myself until 1995, and even then it had nothing to do with my design work. But I kept my eyes open, and it was impossible not to notice what was happening all around me.

Accepting the need to embrace CAD, I faced the huge challenge of finding the time to learn it. As an artist, I’ve always been comfortable hand-drawing everything and soon discovered that I could avoid getting into CAD myself by hiring people to produce the CAD drawings for me. I was frustrated, however, by being once-removed from the process and ultimately signed up for a course.

It meant giving up evenings and weekends for 12 weeks – an enormous commitment and sacrifice on my part. Was it worthwhile? Absolutely!

At 55 years old, I actually feel revitalized: The things I’ve recently learned and added to my practice from the computer realm have been enormously beneficial. I’m also aware that any additional training I tackle will only help me stay marketable and do a better job for my clients.

What I found is that learning CAD is much like learning a new language. Until you get the hang of it, everyone around you is too fluent to be fully understood: You spend a lot of time not knowing what they’re talking about and struggling to get up to speed. And all the while, you’re aware of the fact that learning this language has become a basic job requirement!

Even in a practice as small as mine, getting the new language down is really what it boils down to. I have to have a running dialogue with consultants and others I work with and be able to understand what they’re saying and doing. After spending some time among the proficient, I truly believe that those who refuse to learn this language will ultimately be left behind professionally.

PIECING THINGS TOGETHER

I’d gone to college to become an artist, never dreaming that computers would be an integral part of my life.

I entered the University of Oregon in the 1960s as a fine-arts major and wanted to make a career of it. But Oregon is a beautiful place to become distracted, and I developed a love and passion for the outdoors through mountain climbing, hiking and backpacking.

As fate would have it, I met a professor of landscape architecture who subsequently became my boyfriend and introduced me to what he was teaching. Before long, I switched my major to outdoor education and recreation and completed my undergraduate degree in that field. I then went on to graduate school at California State Polytechnic University at Pomona, where I received a master’s in landscape architecture in 1980 on my way to earning a landscape architect’s license in 1984.

The academic program I chose pointed me toward large-scale land-use projects and land-use planning, yet I began my professional life with a firm that reoriented me toward residential projects. One thing led to another and, by the late ’80s, I had a thriving business on my hands.

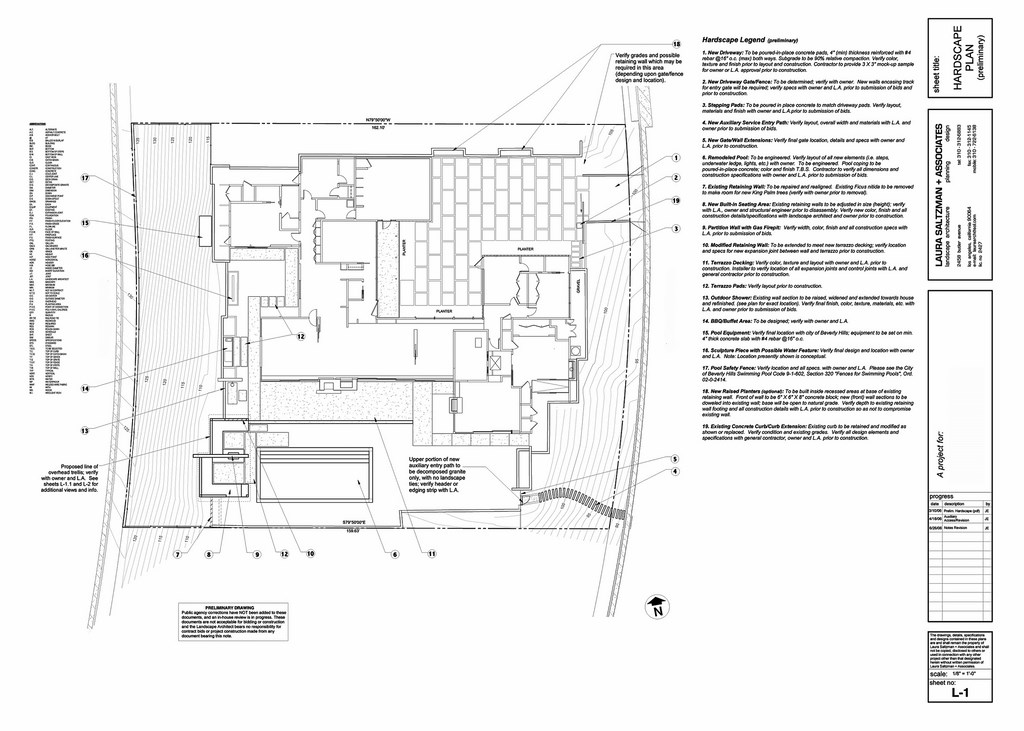

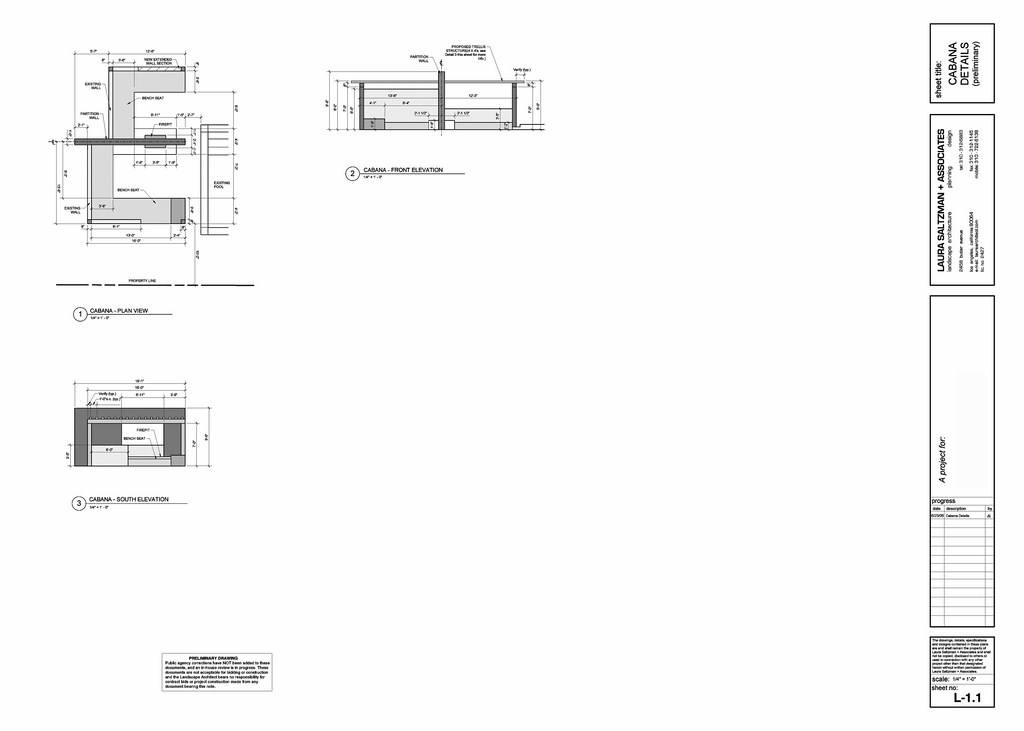

| It didn’t take me long to develop an appreciation for the output of AutoCAD systems and a crisp precision that brings clarity to discussions of scale, spatial relationships and dimensions. But these drawings and details are too flat to be of much help in giving clients and contractors a clear idea of how everything works on site. |

As my business grew, I became incredibly busy and had to hire people to assist me. My main task was simply getting projects on paper: I was designing, drawing, doing paperwork, bidding and installing – and in time, wearing all those hats simply became overwhelming.

This is what I’d been trained to do – that is, draw hardscape, planting, irrigation, grading, drainage and exterior-lighting plans as well as construction details for many elements in my designs. Strict guidelines always governed what I was able to do, so structural and civil engineering were off limits and required collaboration and consultation with outside specialists.

In other words, most projects are a team effort in today’s world. Landscape professionals wear many hats, and we can’t be experts at everything. So I hired the help I needed and the jobs were completed.

But all the while, the pace kept quickening. Working with these other professionals showed me just how rapidly the industry was converting to computer-generated plans and drawings. Through the late ’90s and into the new millennium, I watched as hand drawings disappeared from many firms in favor of CAD-generated plans, elevations and perspectives.

GETTING PROGRAMMED

Not wanting to be left behind, I began by purchasing Mini-CAD for use in my office. At the time, this program was less commonly used than other programs, but it had the advantage for me of being less costly.

At the same time, I was experiencing issues with employee turnover. One associate would learn the program and then move on, leaving me to start all over with a new hire. My frustration with this cycle led me to the conclusion that I could wait no longer: I needed to invest my own time and energy in learning CAD.

It wasn’t long before I enrolled in an online course through UCLA’s Extension program, and it makes sense on an ironic level that the first online course I ever took was about using a computer. (As a side benefit, I gained quite a bit of overall computer proficiency during those 12 weeks by virtue of taking the course online.)

The sessions were structured so that I would read the lectures online and submit homework to the instructor in addition to doing a research paper and taking a midterm and a final examination online. Those exams were given during a large block of time on a particular day, which offered me plenty of flexibility.

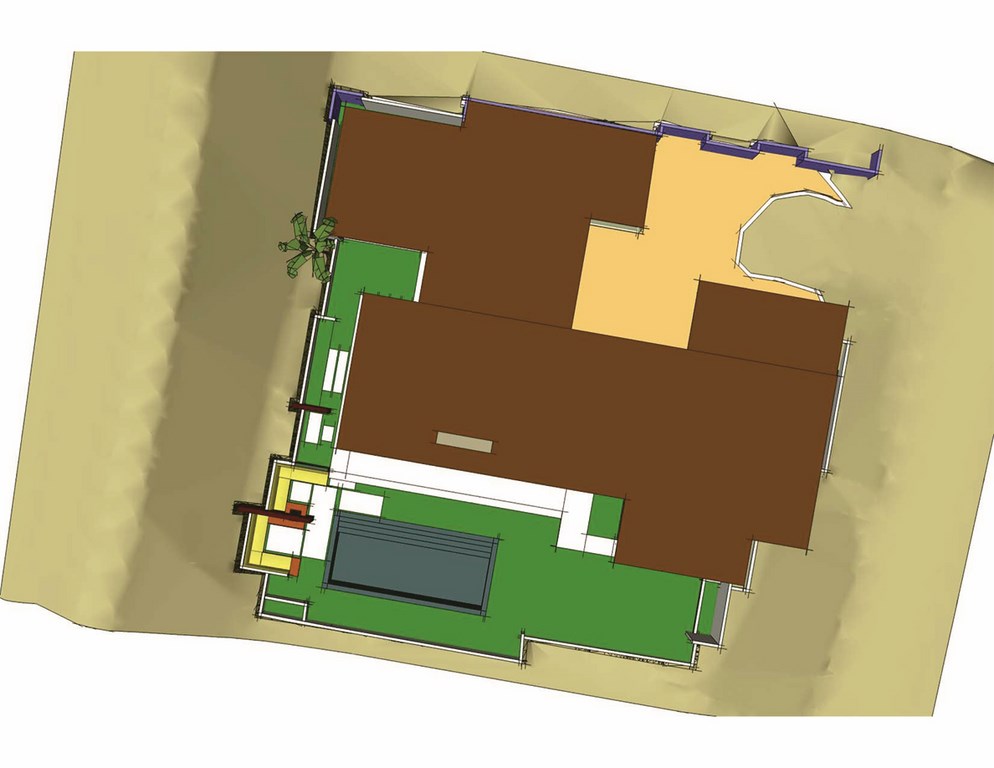

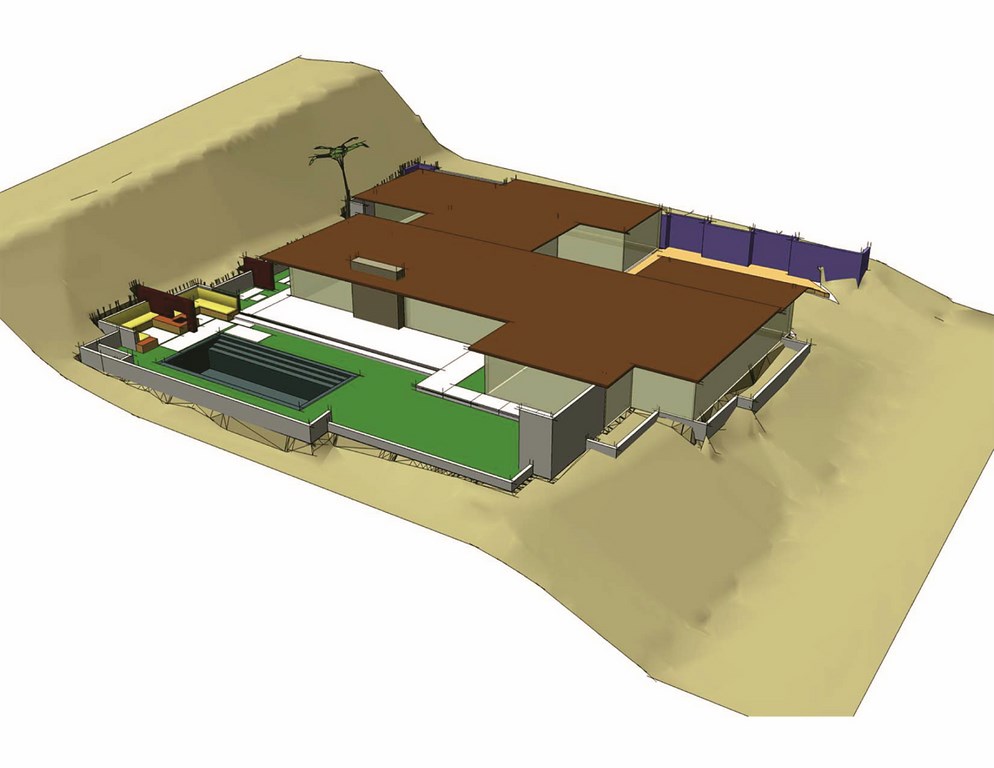

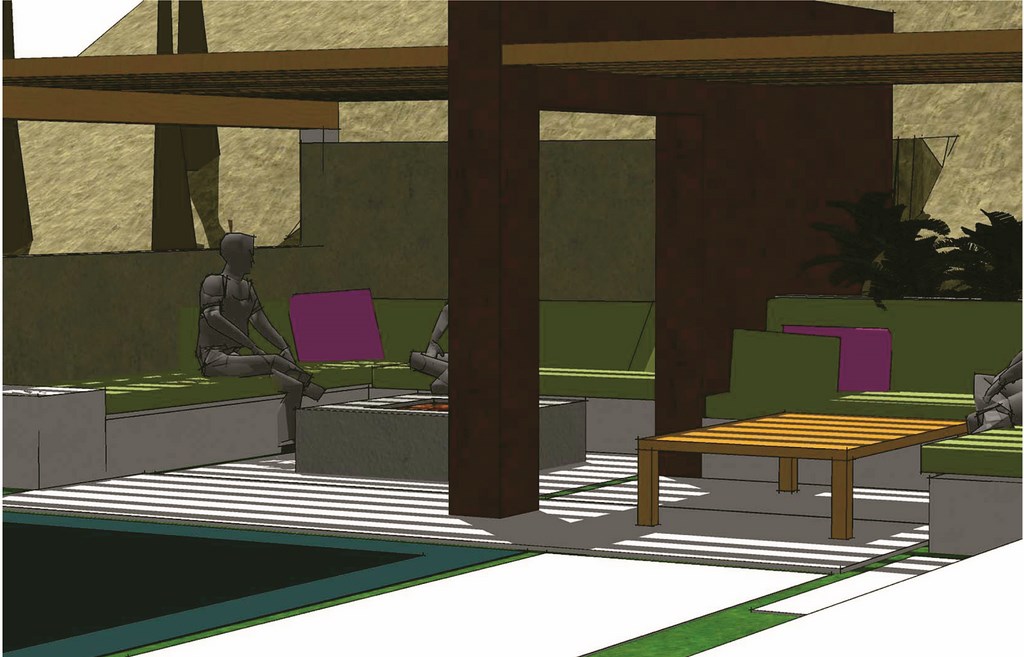

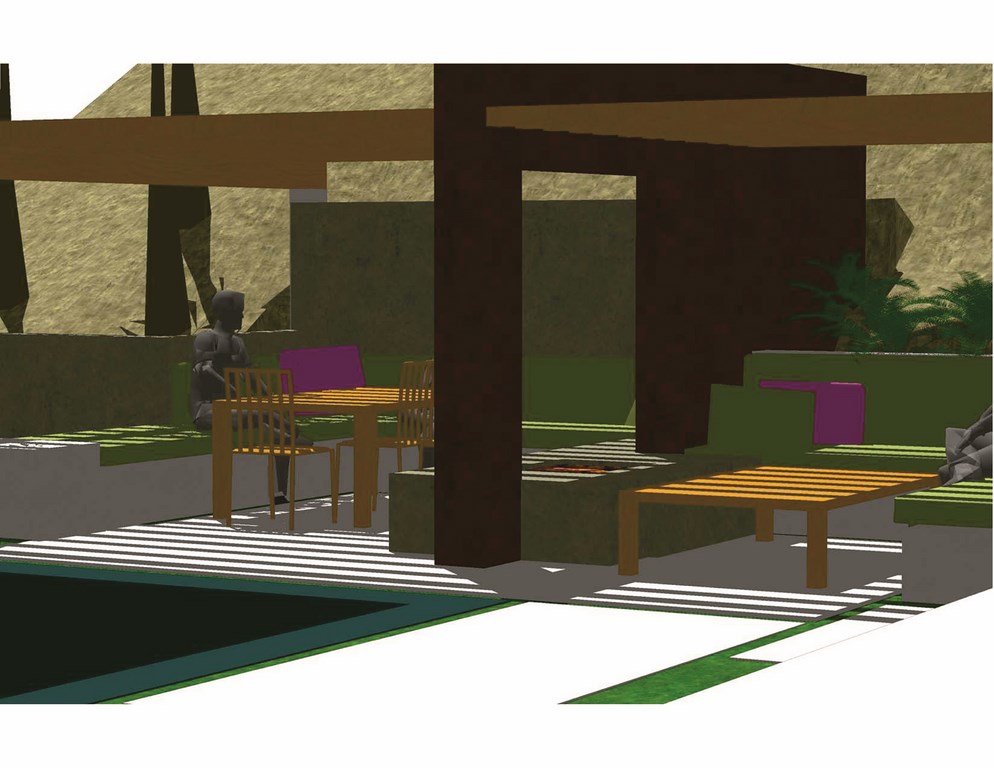

| Once I discovered modeling programs, any issues I had with computer technology were set aside once and for all: The ability of these programs to start with a plan and develop extensive three-dimensional imagery is a huge help in getting clients to visualize a project and walk through the spaces with me on a virtual tour. |

From the start, I knew that keeping up with the pace of the course was critical – and if I didn’t I would fall behind quickly. The instructor had prepared us to spend 12 to 15 hours a week on our studies, but more often than not I was spending 20 to 25 hours at my keyboard and monitor each week.

For busy people, however, the value and convenience of this type of course are immeasurable. Having the option of doing my coursework and taking tests when my schedule allowed ultimately made it possible for me to learn CAD. If I’d been required to drive to campus, sit in a classroom and be there for a set time, it would never have worked: It simply would have been too disruptive to my practice and, overall, simply too time consuming.

The subject of the first course I took was beginning AutoCAD for landscape architects, which, along with Vectorworks, is commonly used in the landscape trades. Knowing one or the other is to anyone’s benefit, particularly when it comes to generating plan views and elevations. The technology keeps changing, of course, and I’m determined to keep up with whatever comes on the market.

NEW TOOLS

One of the most significant additions to the growing lineup of design-oriented programs I’ve learned has to do with perspective drawings: The program is called 3D SketchUp, a three-dimensional modeling program that was easy to learn and has enabled me to translate my flat designs into three-dimensional formats with relative ease.

All I do now is input a CAD design into SketchUp and then the program turns out a three-dimensional model on the computer that enables me to show clients their design from different vantage points. For me, gaining access to this tool has made every second I’ve invested in my personal-computerization project worthwhile.

The files SketchUp produces for me have a hand-drawn quality that makes them fully presentable and more artistic. Basically, this is the program I’ve been waiting for throughout my career, and all it took was an additional eight-hour class to arm myself with this extremely powerful tool.

I still believe that a hand-drawn rendering says more about its creator than any computer-generated drawing ever will, but this technology puts the automated version in a close second place in my estimation.

| I’ve found the modeling program to be particularly useful as a design tool in that I can take a modular approach to key details and help myself (and then my clients) weigh sets of possibilities. Should the cabana have a firepit and a table, or will two tables be the right approach? Moving back and forth between concepts couldn’t be much easier. |

I also have found great value in Adobe Photoshop, which allows me to adjust colors or remove portions of images – another fabulous presentation tool. Beyond improving portfolio shots, this tool lets me manipulate photos and graphic images to show clients my work in a better light. I can, for instance, take power lines or flaws out of a photo and superimpose trees or other items into a view to help clients visualize a setting in great detail.

As I’ve immersed myself in these technologies, I’m finding that more and more of my clients are expecting digital imaging of their jobs – particularly on the high end. These people know what’s available to them as far as visualizing their projects is concerned, and they expect to see me use those tools to the fullest.

More than anything else, however, what this new technology does is speed processes and save time as well as resources. Where I work, for example, the nearby freeway traffic is horrendous and nobody wants to drive anymore. Digital imaging allows me to e-mail drawings to clients, eliminating the time, expense and occasional inconvenience of in-person meetings.

The ease of these exchanges also allows for quicker give-and-take on ideas, thereby speeding agreement and, in many cases, shortening the design process. There can be snags, of course, but my experience is that it’s often easier these days to move processes along electronically than it is in person.

SHARED VISION

To me, my job is all about helping clients visualize designs correctly and giving them the information and drawings they need to see things clearly enough to make a commitment. That can be a huge hurdle in many cases, and we all know that what we’re seeing in our minds and what they’re seeing in theirs can sometimes be worlds apart.

After practicing for almost 30 years, I concede that sometimes even I don’t see things as accurately as I should. Whatever tools can be employed that will allow me and my clients to reach a shared vision of what the design will look like can only work to my advantage.

This is where SketchUp has proved invaluable: It allows me to position myself (and my clients) within a design to see what it will look like from many angles. It enables me to show clients what it really feels like to be in a space – above it, around it, in it, sitting over here or over there, or sitting in the house looking out through the windows.

|

Due Credit My current associate Jim Evans gets credit for the SketchUp images that he created. The design is mine, but he produced the images. We worked on them together in the office and he did them under my direction but again, he was the computer operator. — L.S. |

I’m not quite there yet, but someday when I’m skilled enough I envision taking a laptop computer to clients’ homes and “walking” them through designs using 3-D modeling – something I can’t do with a single drawing. On that level, the computer becomes a sales tool: The more clients can see of their designs, the more likely they are to buy into those designs.

As the process moves forward, revisions are much easier to handle with a computer than they are with hand drawings, particularly when we exchange information via e-mail. Manual erasing and redrawing are very time consuming, not to mention pains in the neck. With CAD, however, all it takes is highlighting the section I need to change and hitting the delete key: It’s gone, I make the changes and move on to the next task.

We all know such changes are inevitable, even after drawings are “complete.” CAD reduces the time involved in making these revisions, and I for one am grateful for the assist. Another virtue of these programs is that most can be used together. You’re able, for example, to import AutoCAD files directly into SketchUp to develop the 3-D models – it couldn’t be much more direct or hassle-free.

Beyond all these benefits is one more: If you’re someone who is not artistic or has only marginal drawing skills, you jeopardize your professional credibility when presenting clients with hand-drawn renderings. A better course by far is letting a computer create visually appealing images that make your ideas truly presentable.

NO TECH TO HIGH TECH

Whether you can draw or not, the time savings to be realized with CAD is simply amazing. I don’t think hand drawing is obsolete by any stretch of the imagination – in fact, all my designs start with hand drawings – but there’s no comparison between the time commitment needed to generate hand drawings compared to generating computer documents.

A simple perspective can take a couple of hours with a program such as SketchUp, whereas a hand drawing can take days. Most of us simply don’t have that kind of time anymore.

There’s also a substantial teamwork advantage and competitive edge to computer usage. It allows me to share files with other project participants, including structural engineers, architects, designers and even computer-literate clients. I’m actually dealing with an out-of-state client with whom I send files back and forth. I’m not sure how we would have managed the project otherwise (within a reasonable timeframe, anyway).

| The capacity to move freely around and within spaces is a principle virtue of the modeling program. When combined with details including shadows, textures, colors and plantings, it’s a package that helps clients visualize things clearly – and also gives me a way to help contractors and subcontractors ‘see’ exactly the sorts of relationships we’re after with respect to materials, joinery and overall appearances. |

This sense of portability is hugely reassuring to me as a professional. If I decide to move, for example, I could maintain contacts I’m leaving behind while building business in the new location. And if I ever decided to close my sole proprietorship and hook onto another firm, my working knowledge of AutoCAD makes me much more attractive to a prospective employer.

There’s no question that making the change from hand drawing to computer drawing is scary, and I’ve spoken with a number of my older friends in the business who have expressed concerns about whether they’d be able to get through a class, let alone “get” the technology. In my experience, you have to be diligent and do your homework, but that involves simple determination and shouldn’t be a deterrent, particularly if you intend to keep practicing.

Ours is a profession for which many people feel great passion well into their careers, and I’m among those who will keep at it for the rest of my life. As I watched hand drawings disappear from offices, however, it was all the sign I needed to get me to change my ways and jump on the train.

As with any language you learn, you have to keep practicing. If I’m not actually doing computer drawings for clients, I keep doing practice drawings on my own so I don’t forget the skills I’ve learned. Once you get past the steep learning curve, they’re actually enjoyable and I find keeping up and learning new tricks to be a challenging sort of fun.

Professionally rewarding, too!

Laura Ackard Saltzman is a licensed landscape architect and has been owner/principal of Laura Saltzman + Associates Landscape Architects for more than 26 years. She recently returned from her fifth Himalayan trekking expedition and has traveled extensively throughout Nepal, Tibet, Bhutan, India and more. Previously involved in a wide variety of projects including multi-family and low-income housing developments, government/urban transportation facilities, private parks and institutional and commercial facilities, her firm now specializes almost exclusively in high-end residential design work and has handled projects using virtually every architectural style commonly seen in the Los Angeles area. Through the years, Saltzman has welcomed projects ranging in size from a residential balcony to regional planning, seeing them through from concept to completion of construction. Her work has been profiled in a number of publications, including the Los Angeles Times Magazine.