By Tim Lindsay

A well-conceived garden that has endured through many decades can teach us all a multitude of lessons. In the case of the Virginia Robinson Gardens, however, even getting to the point where those lessons might be recognized and appreciated has taken years of research, study and painstaking restoration.

In the nine years I’ve been associated with the gardens, I’ve done all I can to determine the original design intent of those who owned and established it, stripping away generations of alterations, additions and miscalculations while interpreting the site and uncovering clues that point to the sense of mission and the creative spirit that influenced its creation and further development early in the 20th Century.

I’ve done so with a recognition that the Virginia Robinson Gardens are important as an emblem of southern California history and an era gone by. I’ve also come to perceive the complexity, artistry and beauty of the space, seeing it as a blueprint that, examined closely, can serve to inspire and inform the work we all do today.

The current gardens occupy most of the grounds of the former estate of Harry and Virginia Robinson, heirs to a department store fortune. My charge has been to restore and manage these six-and-a-half acres in the heart of Beverly Hills, Calif. – a graceful setting in the midst of a storied community, living testimony to the original owners’ passion for natural beauty and a great laboratory for preserving a 20th-century sense of gardening tradition.

PERSONAL NARRATIVE

The knoll on which the gardens sit was “discovered” at a time when what is now one of the most affluent spots in the nation was still rolling hills, pastures and fields.

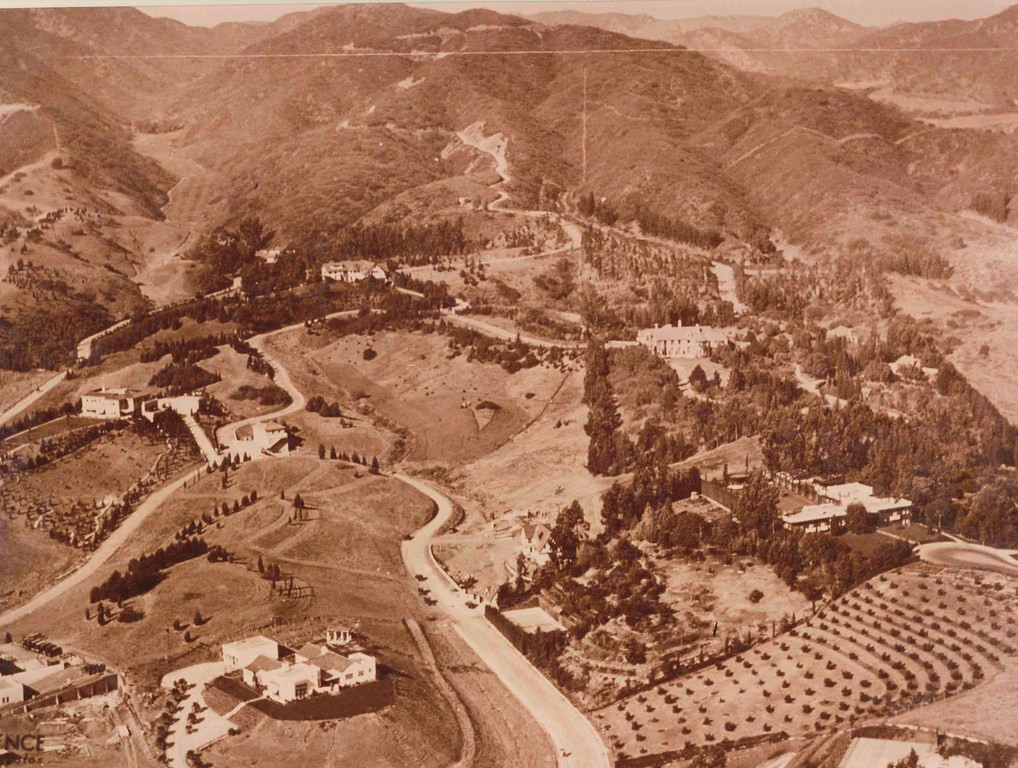

As the story goes, the Robinsons lost their way while heading for the Los Angeles Country Club one day in 1904 and ended up in a spot overlooking the emerging Beverly Hills area. Inspired by views stretching to the Pacific Ocean and San Gabriel Mountains, the newlyweds purchased 15 acres from a gentleman running a real estate shack down the hill on Sunset Boulevard. A house was designed and built for the newlyweds by Mrs. Robinson’s father (for a mere $25,000) and completed sometime around 1911.

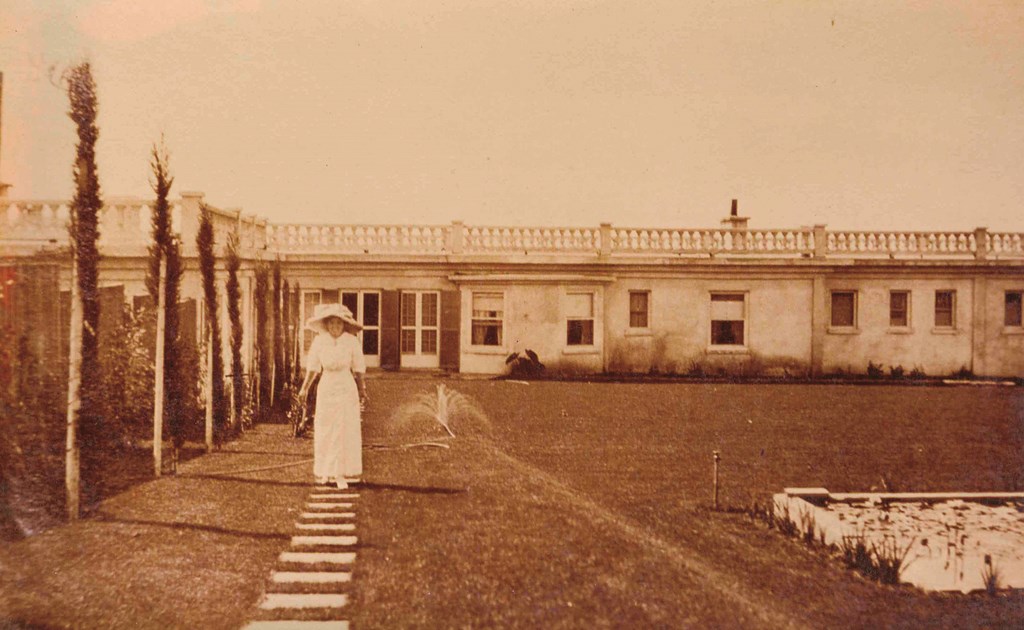

| Beverly Hills was largely undeveloped when the Robinsons made a wrong turn and found their hilltop property, but almost from the beginning they had upscale neighbors: Directly across the street stood Pickfair, the legendary home of early Hollywood stars Douglas Fairbanks and Mary Pickford. As her garden grew, Mrs. Robinson was known to walk its paths daily, making certain everything was coming along as she wished. |

The Robinsons epitomized the height of society and the formality of their day. Their staff of 21 was trained in same protocols used in the White House – a level of refinement observed until shortly before Virginia Robinson died in 1977. But when it came to the garden adjacent to the new home, there doesn’t seem to have been any sort of formal master plan.

Instead, as their wealth increased, the couple’s garden kept expanding and evolving, section by section, until it covered the six-and-a-half acres I manage today. The remaining eight-and-a-half acres were undeveloped (presumably serving as orchards) and were sold off by the Robinsons in the early 1930s.

In years of investigation, I have yet to discover any scrap of documentation or any sort of plan for the site. I’ve come to believe that this garden was simply a labor of love for Mrs. Robinson and that it developed as time passed and as money and energy allowed. The Robinsons had no children, and I’ve always thought that she transferred much of her love to the garden.

| Starting at street level, the Palm Garden features cooling pathways that lead down from the driveway to the Cut-Rose Garden at the bottom of the hill. The views that open between the tall specimens bordering the paths are a feast of variety: All of the palms originated in Australia, and many of the specimens seen here are found nowhere else in North America. |

What we do know is that the original layout consisted of five distinct, themed gardens: the Italian Terraced Garden, the Rose Gardens, the Front Garden, the Kitchen Garden and the Palm Garden. In creating these spaces, Mrs. Robinson was always involved behind the scenes, communicating her ideas and wishes to her gardeners.

She was so engrossed in the development of the spaces that in a sense this became her primary occupation: She spent much of her time walking the paths, studying the plants and features and discussing ideas with Ivo Hadjiev, her major domo. These walks and discussions were supplemented with feedback from prominent horticulturalists, designers and architects she’d invite to the gardens from time to time.

HISTORICAL PRECEDENT

At the close of her 66-year residence on site, Mrs. Robinson bequeathed her estate to the Los Angeles County Department of Arboreta and Botanic Gardens with the hope it would be maintained and preserved as a botanical garden for the promotion of horticultural excellence. Currently, the arboretum, along with Descanso Gardens and the South Coast Botanic Gardens, operate under the auspices of Los Angeles County’s Department of Parks and Recreation.

| The Cut-Rose Garden was the most disrupted of all the spaces on the property during the time the county used the estate as an experimental station for plants. This entire area had been planted with Chorisias, since removed (with a couple of exceptions); for some years now, we have been replanting the area with roses available when the garden was first developed. |

By 1979, the site was listed on the National Register of Historic Places. In addition to county funding, the gardens are maintained through a charitable organization – the Friends of the Robinson Gardens – and an endowment left by Mrs. Robinson. These funds supplement the county’s contribution to the restoration, preservation and operation of the home and gardens.

From 1977 until 1997, the county generally focused on plant experimentation and used the site as a venue for testing tropical plants and other species that wouldn’t grow in any of its other facilities. Situated seven miles from the ocean and offering a unique microclimate, it was a great place for the county to try out new plants – which they shipped over from the arboretum by the truckload with instructions for the gardeners to “find sunny locations” for them.

The gardeners would proceed to stick the plants where they could, without regard for their maturity or the surrounding vegetation or any other important design or site considerations. The garden, as they saw it then, was to be an experimental station – a redefinition that carried the place well away from the Robinsons’ original design intent.

| We’ve been relieved to find that the county’s experiment-oriented treatment of the gardens did relatively little damage to its basic structures and plantings, but certainly some harm was done through the years. Planting fast-growing Shamel Ashes close to this pathway, for example, did its brickwork no favors, but it will be simple to restore the stairway to near-original condition when the time comes. |

When I arrived at the Virginia Robinson Gardens in February 1997, I took on an entirely different mission: to determine the original design and intent of the gardens, consider proper exposures and correct plantings – and then decide how it could all be restored. In other words, it was left entirely up to me to determine the direction the gardens were to take going forward.

One of my first observations was that turning the gardens into an experimental venue was far from the best use of the site. Immediately, I began a long process of restoring the gardens, preserving their fascinating history and establishing the grounds as a place to educate the public now and in the future.

LOOKING BACK

Before I stepped into my role as superintendent at the Virginia Robinson Gardens, I had worked for the country arboretum and had visited the Beverly Hills site for a couple of meetings – and that was it. When the gardens’ previous director became ill, I was sent over to consult and prepare the garden for various fundraising events.

| The Formal Rose Garden is a tidy space these days, with its roses reflecting varieties that would have been available in the years when Mrs. Robinson originally planted it. Here and elsewhere, the assistance of Ivo Hadjiev, who was with her through years of the gardens’ development, was of amazing help to us in returning the gardens to their original glory. |

Once I became superintendent, I saw the need to develop an in-depth understanding of which plants were original to the gardens, which had been introduced experimentally and which were volunteers or opportunists that had been allowed to establish themselves. Assisted by Ivo Hadjiev, I began to develop a sense of what belonged and what didn’t.

We started by determining the ages of various plants and then examining lines of sight. Before long, we were able to clarify key elements of the original layout and plantings. One of the more obvious points of departure is a central axis that cuts through the Italian Terraced Garden. A brick pathway bisected by a runnel and other waterfeatures gave this space a distinct formality, with terraces expanding out from the central axis and carved into the hillside.

Additional clues we found on site helped us understand how the gardens had once appeared, including the olive trees that still exist on the south end of the property. It hints at remnants of the 19th-century landscape and the fact that the foothills here were transitional from the citrus orchards of the San Fernando Valley to the beans and other crops that flourished in the more ocean-influenced climate to the south.

After establishing the basic bones of the garden, we began looking at where sun-loving shrubs had become overshadowed by overgrowth and the untended seedlings that had been allowed to grow into full-sized trees. By this time, it was becoming clear to me that my preservation mission and 20 years of the garden’s use for experimentation were entirely in conflict.

| The Italian Terraced Garden is the most extensive of the original garden spaces, cascading down the hillside with spaces that delight the eye, please the olfactories and transport visitors to another time and place. Circuitous garden paths are accented by formal architectural spaces, and along the way, guests are treated to a huge variety of plants, colors, textures and contrasts. |

The plants the arboretum had introduced came from all over the world and had been incorporated into the gardens with the main intent of evaluating them for introduction to the landscape trades in southern California. This wasn’t a bad idea by any means, but precious little had been planted in a way that respected the original gardens.

In fact, Mrs. Robinson’s rose garden had been obliterated and replaced by various other plants and trees. By the time I arrived, none of her roses were left, which means the best we could do was repopulate the collection with varieties we knew existed at the time of the original planting. Using Hadjiev’s memories of the way things had been, we think we’ve recaptured much of the spirit of this space.

FINE TUNING

Hadjiev’s assistance was indeed crucial as we moved from space to space. His stories about the rose garden proved invaluable (how ‘Eiffel Tower’ was her favorite climbing rose, for example), as did his reminiscences about the way Mrs. Robinson would send gardeners down to the cut-rose garden to bring bundles up to the house for parties.

Through this long process, we discovered that the arboretum’s experimentation had struck only a glancing blow: Once we completed our surveys, we were confident that the vast majority of the plants on site were in use when Mrs. Robinson was alive and that only about 20 percent had been moved here for use in the arboretum’s trials.

| One of our key challenges was isolating the gardens from a city that is now crowding its borders on all sides. We’ve set up screens of trees and hedges to block out homes that now surround the estate; it will be some years before these barriers truly block out the encroaching world, but we’ve always seen our task as being long-term in nature and as one of preserving these spaces for future generations. |

As superintendent, I forged ahead with my mission. Working with a staff consisting of a head gardener, two assistant gardeners, two grounds-maintenance workers and three interns, I began by editing out all extraneous trees and shrubs and pruning trees to reestablish exposures and views. We knew a theme had existed, so we stayed within the observable framework in processes that amounted to constant fine-tuning.

Along the way, I’ve added new cultivars without concern about their being fresh introductions or the products of the hybridization assembly line: Given the open nature of the restoration, I preferred instead to judge potential introductions by their character and fit within the garden, being cautious and conservative every step of the way.

I liken restoring these gardens to the work of an interior decorator: If you put new carpet in a room, the furniture looks old; if you revive a room by painting the walls, it puts everything in a different perspective. In this context, it’s easy to bring in a newly hybridized plant so long as it helps in building a composition that makes sense without throwing things off balance.

| The Front Garden is the stuff of understated elegance, with colorful plantings, garden statuary and a well-established Wisteria giving the space a wonderfully welcoming air. |

I used, for example, Pittosporum tenuifolium ‘Silver Sheen,’ a relatively new introduction to the southern California nursery scene, because it has the same foliage color as the gardens’ old Magnolia trees. Their color balance allows them to work together in conjuring a classic, period feel.

We also incorporated African boxwood (Myrsine africanus) into the Italian Terraced Garden to give better definition to this area. This particular plant seemed a better choice than traditional boxwoods, as the colors of the African Boxwood worked better with the terracotta color of the hardscape.

In all cases, it’s been about finding the right plants to maintain consistency. I’ve always approached things from an artistic point of view, but in my work for the arboretum I had been forced to think in natural rather than historic terms and in terms that placed botanical and scientific methodology above art. That experience was essential to my professional development, but I was now in a position where I could view each plant based on form, color and the degree to which it fit within the master composition.

CURRENT ACTIVITIES

Once the basic restoration project was under control, we began to look at a bigger picture and saw the need to screen the gardens from neighboring properties.

When the home and gardens were first built, this was the only property north of Sunset Boulevard, an area now thoroughly subdivided and developed. Houses now border the gardens on all sides, creating unintended views – both from the neighbors’ perspective and from that of visitors to the gardens.

| Some of the most satisfying spaces on the estate have nothing to do with the established gardens. One such space is a transition point where a gate separates the Formal Rose Garden from the pool terrace; another is where a small musician surrounded by orchids dwells in a pocket just outside the kitchen. It’s a home where attention was paid to every detail, and bringing it back to its original glory is both a privilege and a labor of love. |

Questions from visitors about these neighboring houses and their different architectures tended to cause confusion. Thus, despite the fact that many neighbors enjoy their views of the gardens, we’ve decided to screen them all out for the sake of historic consistency.

A particular challenge we faced with one neighbor was winning her cooperation to remove and prune large trees hanging over the rose garden across her property line. It certainly helped that she was on our staff as a docent, and we worked things out in ways that improved the appearance of her property line while enabling us to get enough sunlight to drive the restoration of the rose garden.

| The Kitchen Garden is the most intimate and perhaps most charming of all the garden spaces. Compact in size but rich in variety and equipped with its own hot house, it recalls a time when going to the supermarket wasn’t a daily event and households such as these tended to be much more self-sufficient than their modern counterparts. |

The arboretum staff had attempted some screening in the past, planting a row of Shamel Ash trees at the base of the Italian Terraced Garden. These fast-growing trees have very invasive roots, however, and damaged the steps leading from the bottom of the garden to the upper terraces. We replaced the Ashes with Olive trees and then planted Bay Laurels in front of the Olives as a secondary buffer.

Even more dramatic changes were needed to restore the Cut Rose Garden, which had been entirely replaced with Chorisia trees by the arboretum staff. Although it’s difficult to destroy established trees and plants, we had to remove all of those Chorisias and reintroduce the roses Mrs. Robinson cherished.

We know at this point that our work with these gardens will be long term and ongoing – a project that will last for our lifetimes and beyond. In that sense, a garden is never finished: It’s a natural thing that continuously evolves, even in the case of historic properties. Our plan going forward is to continue to introduce plants that fit the original intent as well as to continue refining the palette we believe existed from the start. I see these as companionable ideas that will effectively combine to maintain the gardens’ personalities.

I love it when I hear people say the Virginia Robinson Gardens are serene, old world or classical and have a way of distracting them from their troubles. As it sits in the middle of one of the world’s busiest cities in one of the country’s wealthiest neighborhoods, it’s just another world – and a place very much worth preserving for generations to come.

Tim Lindsay has been superintendent for the Virginia Robinson Gardens in Beverly Hills, Calif., for the past nine years. His previous experience with the Los Angeles County Department of Parks and Recreation prepared him for the task of restoring and maintaining this historic site. Lindsay is a graduate of Southern Illinois University, where he earned a masters of science degree in forestry and a bachelor’s degree in plant and soil science.