Perfecting a Quartz Pool Finish

Everyone knows that muriatic acid, when applied directly to a plaster finish, will dissolve and remove material from the surface. This is why the practice of “acid washing” is so widespread: It removes surface stains and restores a finish to an approximation of what it looked like when new.

The problem with this acid application, of course, is that it achieves its rejuvenating visual effect by breaking down the top layer of the plaster. This results in a porous and etched surface – damage that can easily be seen under magnification – and properly should be regarded as a short-term fix that makes the plaster even more subject to streaking, blotchiness and staining in the future. While the process does clear away stains and make a pool look impressively “new,” informed professionals know that it involves sacrificing a portion of the plaster’s projected service life.

If these facts are so well known in the pool business, it begs the question: Why, after going to all the trouble of applying a smooth, brand-new, hand-crafted, quartz-infused pool finish, would anyone immediately perform an acid wash on that pool? Yes, it’s a shortcut to exposing the color of the quartz, but isn’t it simultaneously etching and compromising that brand-new surface and shortening its life?

Why, given the fact that there’s a way to achieve the desired, vivid appearance without damaging an exposed-aggregate finish’s integrity, would anyone want to do this?

ON THE SURFACE

I’ve weighed these questions for some time and see two possible explanations for this inclination to overlook the damage high levels of acid can do to new plaster finishes:

[ ] Many applicators carry samples of exposed-aggregate finishes that have been acid-washed to maximize quartz exposure. Theses samples always look good, but they’re never exposed to the leaching effects of water and do not change in appearance over time. Might this lead to a false assumption that acid exposure does no harm? [ ] Porous plaster surfaces can also be more easily scaled by alkaline water than can smooth, dense plaster surfaces. The soluble calcium hydroxide that is dissolved away by acid treatment can just as easily precipitate back out of the water to scale the surface and make it white or opaque. When this happens months after finish application, might it be a natural tendency to trace the problem to water chemistry rather than to plastering or start-up technique?The point to emphasize here is that neither of these thought processes gets to the heart of the matter: When it comes to achieving good exposure of the quartz color, a far better way to go involves proper troweling timed in such a way that it removes the weak, watery cement cream (known as laitance) that develops on a cement/plaster surface.

This cement cream accumulates on the tool during hard troweling and should be discarded. Working it back into the surface and effectively leaving it behind as a thin surface layer not only keeps the quartz aggregate from showing up at the surface the way it should, but also creates a filmy, weak surface that will break down, deteriorate and ultimately become unsightly.

Removing this material and disposing of it properly is the best way to go. Removal also helps the applicator avoid using a common start-up routine intended to eliminate “plaster dust” – that is, the frequently taken step of “acid bathing” the finish after the pool has been filled with water. This is yet another means by which a new plaster finish may be etched.

The National Plasterers Council knows that acid and new plaster don’t mix, which is why the group recommends what it calls a Traditional Start-Up Program. The entire purpose of this protocol is to keep acidic, aggressive water from damaging new plaster and recognizes the fact that a new finish is much more vulnerable to acid-related damage than one that is even a month old.

Here’s the point: If a plaster finish begins to show light color blotchiness or streaking within a few months after completion and it is known that the surface was subjected to some sort of acid treatment, isn’t it likely the treatment is at least part of the problem?

DISSECTING THE ISSUES

So where does this leave us if it’s not advisable to use acid to treat a new plaster finish? As suggested above, skillful troweling, well timed and involving disposal of cement cream is one direct solution. Working this way to prevent plaster dust from hardening and covering up the quartz color is, however, a definite hassle – perhaps the main reason applicators resort to the use of acid.

Is there an alternative? Yes, there is – one that involves keeping the plaster dust from forming in the first place. And it’s easy to do, too.

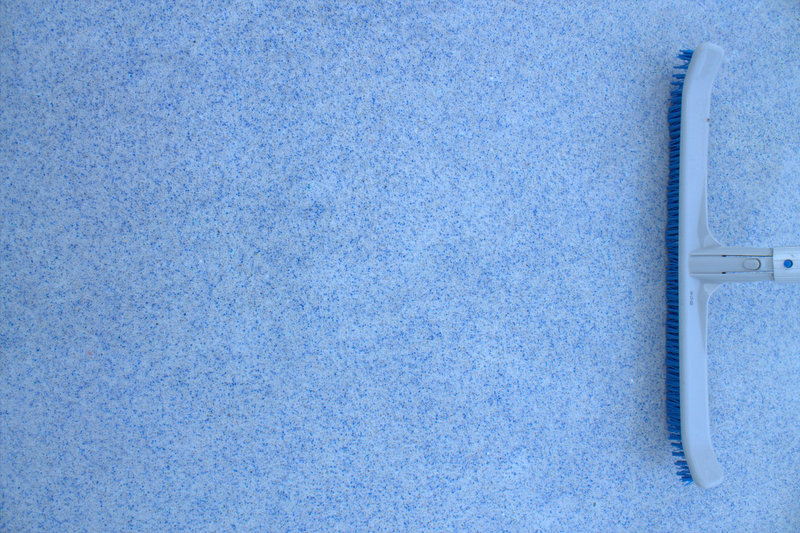

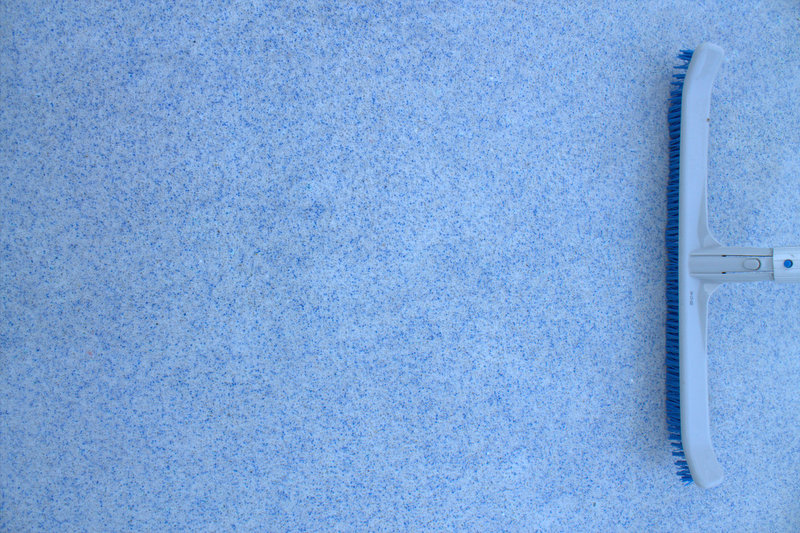

| Note the vivid color of the light blue quartz finish on display here. And this isn’t a new pool; in fact, it’s ten years old, was never subjected to an acid bath or acid wash, had no calcium chloride added to the plaster mix, wasn’t subjected to wet troweling, was filled 12 hours after the finish was applied and was started using the bicarbonate approach. (See the text below for details.) |

People in the industry commonly believe that, as plaster hardens and “cures,” it naturally releases a cement component known as calcium hydroxide. This is not necessarily correct. In fact, the applicator can prevent calcium hydroxide from leaving the plaster surface (thereby becoming plaster dust) and can cause it instead to be converted into calcium carbonate (a much harder material) within the plaster matrix. When this is achieved, the surface is harder, denser and smoother – and no plaster dust develops to foul the surface.

How do you keep calcium hydroxide from leaving a plaster surface? It’s simple:

1) Do not add calcium chloride to the plaster mix.

2) Do not add water to the plaster surface and trowel it in.

3) Delay the filling of the pool for at least six to eight hours after finishing. (If the weather is hot and dry, tent the pool!)

4) Fill the pool with water adjusted to +0.5 on the Langelier Saturation Index. (Using the bicarbonate start-up approach recommended by onBalance will accomplish this.)

The result of following these four recommendations is a pool finish that is smooth, dense, durable and stain-resistant – one that will, over time, actually be polished rather than harmed by a pool cleaner. Moreover and more important to the clients, the color of quartz in such a pool will be vivid, consistent and long-lasting – more than enough to make them happy to have paid a premium for a special finish.

Don’t misunderstand: There’s an important role for acid in watershapes, and it’s obviously an essential component in maintaining clear, clean, balanced water. It’s just a matter of taking the nature of new plaster into account and working with it instead of against it in getting a new watershape started.

There is a better way, and the proof is in a better-looking, longer-lasting pool finish.

For more information on the bicarbonate start-up approach, click here.

Kim Skinner began his work in the pool industry 45 years ago, starting as an employee and eventually becoming manager of Skinner Swim Pool Plastering in Sun Valley, Calif. He later became president of Pool Chlor, a chemical service firm with offices throughout the Southwest. He is also a partner in onBalance, a consulting firm that performs both laboratory and field research on pool-water chemistry and on the relationships between water chemistry and pool plaster surfaces.