Every Boulder Tells a Story

For some time now, watershapers have exploited the fact that naturally occurring rocks and boulders can enhance the appearance of their work. Whether used in conjunction with artificial rock or alone, you appreciate the fact that rock comes in a never-ending variety of shapes, sizes and textures – and that they can be used to add both surprise and individuality to designs.

For the most part, however, designers and builders have tended to work with common local stones – fieldstone, granite or river rock – that limit their palettes when it comes to color, visual appeal and expressiveness.

It can indeed be an epiphany for those who’ve used common stones to come across material that includes complex mineral and crystalline structures or fascinating patterns of stratification that are the product of eons of metamorphic activity within the earth’s crust. With this awareness comes the realization that the palette is virtually limitless and that rockwork can now easily be found to echo the colors and exceptional nuances found in decking, interior finishes and plantings.

DIGGING DEEP

Our company is in the business of supplying unique and beautiful rocks to professionals who want to increase the individuality and value of their work.

One of my functions at Western Rock & Boulder is to seek out new sources, a job that takes me to various sites around the country in search of natural beauty. What I’m after are architectural gemstones, materials that work perfectly in high-design watershape and landscape settings. Basically, they’re waiting to be put on display, ready to tell the story of millennia spent under the most extreme influences of our planet.

Let me say right up front that many of these rocks are expensive – definitely not for every installation. But when they find their ways into projects where clients want something truly special, the effect can be dazzling.

|

Origins and Species When you use interesting rock material in your work, it helps to know a thing or two about geological history. You can share this information with clients – and at times use it as a way to express and capture the value of the material in the design. Here are some examples of the rock types we’re familiar with at Western Rock & Boulder, along with geologic histories presented in brief: [ ] Massive White Calcite. This coarse, crystalline rock is almost entirely composed of the mineral calcite (calcium carbonate, or CaCo3). The principle constituent of limestone, calcite is one of the most common rock-forming minerals found in nature. Most limestone is composed of particles and fragments of calcite that were originally the hard portions of marine invertebrates such as clams, brachiopods, snails and coral. Eons ago, this material accumulated on the ocean floor in the shallow portions of warm, tropical seas. With burial and compaction, this material became limestone. Heat generated by volcanic centers can attack and alter the limestone, as seen here. The unusual patterns result from vein calcite that was deposited in fractures within the host limestone. The yellow, pink and orange stains are from various iron oxides derived from pyrite, or “fool’s gold.”

[ ] Gray Jasperoid. Jasperoid is the term used by geologists to describe a fine-grained, dense, hard rock consisting mostly of quartz. Jasper, as it is more commonly known, is a precious/semi-precious stone – a cryptocrystalline quartz typically seen in red, yellow or brown shades. The specimen seen here was derived from a Devonian-age carbonate parent called Devil’s Gate limestone that originally formed in a shallow marine environment some 360 million years ago. At a much later date, hot mineral-bearing solutions attacked the limestone and replaced the calcite particles with finely crystallized quartz. The resulting rock is much harder than the original and quite susceptible to brittle fracturing. This rock probably derives its color from the original limestone material: The white crystalline calcite acts as a kind of cement gluing together pieces of jasperoid together. The pink tint is derived from the iron oxide mineral known as hematite (Fe2O3) created by the oxidation of iron sulfide, also known as iron pyrite or FeS2. [ ] Devonian Limestone. Seen here is a typical example of fine-grained marine limestone. The color of this rock is a mixture of pink imparted by hematite and the oxidation of iron pyrite and a white/gray crystalline material that is basically calcite – but which has been altered in the process of gold formation. The pyrite was deposited from hydrothermal solutions; in the process, fine (micron-sized) particles of gold were deposited on the surface of the pyrite grains. The slabby nature of some of the limestone pieces is a result of material accumulating in flat beds of debris. These flat surfaces are former bedding planes. [ ] Skarn. This laminated, crystalline specimen is an excellent example of so-called “contact metamorphic” rock. The term refers to rock that has undergone significant changes as a result of heat and pressure. In this case, the original was a sedimentary rock, predominately bedded shale (or mudstone) interleaved with limestone. This sedimentary sequence took place during the Cambrian period, hundreds of millions of years ago, in an ancient shallow sea. Later, the section from which the pictured rock was taken was penetrated by granitic rocks during the Cretaceous period – the time of the dinosaurs – about 105 million years ago. Heat and fluids from molten granite “baked” the adjacent shales and limestone, converting them to a crystalline metamorphic rock. Skarn is a Swedish mining term referring to replaced limestone and dolomite, a combination referred to as carbonate rocks that includes large amounts of iron, silicon and magnesium as well as minor amounts of silver, copper, zinc and gold. Immense heat combined with some of these introduced elements changed the carbonate rocks into new silicate minerals, including garnets, pyroxenes and wollastonite. These new minerals are much harder and more durable than the original parent limestone.

[ ] Hornfels. Like skarn, hornfels is an example of contact metamorphic rock. The word contact here means that the rock formed in the contact zone between an older sedimentary section and intruding granitic rocks. Hornfels is a German term meaning “horn rock” and calls to mind the hard, fine-grained, flinty nature of the material. Hornfels, skarn and marbles differ in appearance, but they are all examples of contact metamorphism. Marble is a heated and recrystallized limestone or dolomite; hornfels are formed in much the same way, but from fine-grained carbonates or shale. The green and gray colors of hornfels result from fine crystalline intergrowth of pyroxene, feldspar and quartz. These minerals were created by heating the sedimentary particles of clay grains, fine siliceous mud and silt along with fine detrital fragments of calcite. At the high temperatures, these mixtures became chemically and structurally unstable and re-combine to form more stable substances. The result is a rock that is both hard and dense – and among the most durable rock types in the world. [ ] Vein Quartz. These spectacular masses of quartz were found in the foothills of the Sierra Nevada range in Central California near the famed Mother Lode, which drew thousands of prospectors to its hardrock goldmines in the years after gold was discovered in 1849 at Sutter’s Mill. Blocks of this sort of inter-grown quartz crystal represent barren “footwall” material found in areas rich in gold ore. Truly large quartz crystals such as the ones shown here are somewhat rare, however, and can only form where they have adequate room to grow. This growth occurs where mineral-laden, silica-rich hot waters known as hydrothermal solutions have deposited their mineral constituents in deep fissures within the earth’s crust. These fissures are found in “cut” slate of the Paleozoic and Mesozoic ages and extend to depths of thousands of feet. The form of these crystals is a surface manifestation caused by the rock’s internal atomic structure, which governs the manner in which constituent silicon and oxygen atoms are bonded together. This only scratches the surface when it comes to rock types available for use in watershapes and landscapes. Exotic stones are available in places around the world – every one of them useful in accentuating the beauty of a built environment. – R.B. |

In a design sense, the sort of colorful rocks pictured with this article can be used to complement and create specific feels or styles. In fact, many rocks are synonymous with certain geographic locations and design modes, such as lava used in tropical designs, reddish, iron-laden boulders in Southwestern/desert designs or marble for a classical or neo-classical touch. If you use any rockwork at all, it has to fit the picture or it will detract from the intended effect.

There’s also a “trend factor” here: Just as the jewelry business has been led in recent years to add literally dozens of unconventional, brightly colored gemstones to contrast or complement diamonds in response to customer demand, some of those same customers are pressing architects, landscape professionals and pool builders to expand what they’ve conventionally offered in terms of color, character and texture when it comes to rocks and boulders.

This trend has staying power, however, because the emotional appeal and nuance of these materials is tremendous. When you see large boulders flecked or striated by colorful mineral content, the impact can be awesome – especially when you think in terms of ten-ton boulders, which are pretty impressive on their own. And when you season the composition by setting up contrasts with smaller pieces of more ordinary or even artificial rock, the entire setting takes on a new life and energy.

To many in the trade, in fact, these special rocks present a whole new aesthetic dimension, a new medium with which to create.

HISTORY IN PLAIN VIEW

Beyond the immediate visual impact, there’s something special about a material that has a history reaching back millions of years.

Indeed, when you link the immediate beauty of these rocks with an appreciation and understanding of their origins, the value they bring to a watershape can be even more considerable. I discuss geological basics in the sidebar below; here, suffice it to say there’s a value in the pride a client will find both in owning an impressive boulder and in being able to share some of its story with friends and visitors.

|

Sharpness of Line The boulders we commonly work with have been fractured and forcibly removed from the ground, so their surfaces have not been weathered by wind, rain or chemical erosion. This leaves them with sharp lines that are quite geometrical, almost faceted. This characteristic opens them to a wide range of creative placements – just the sort of touch that can highlight a watershape and accentuate its features. Crisp lines, sharp angles and flat surfaces can, for example, make these stones useful as weirs or in channels – or in echoing the geometry of a watershape, pathway or structure. They also can be used to contrast softer-looking materials, causing the stone to stand out against its surroundings. That same sharpness can be softened and made to recede through use of plantings to create even more dramatic contrasts and tensions. The possibilities, it seems, are limited only by the designer’s imagination and creativity. – R.B. |

It’s fascinating to think that our most impressive rocks were formed as a result of ancient volcanic activity – periods of incredible heat followed by extended periods of cooling and settling. And that volcanic past is just part of the tale: In eons since, tectonic movement has pushed and prodded the earth’s crust with brutal force, breaking and interleaving layers and introducing an array of ores and minerals to sedimentary beds. The resulting rock is laced with vivid color, crystalline veining and highly individual character.

The rest of the story involves the fact that such material is not often found on the surface.

Rather, for the most part it is embedded deep within the earth, and great effort and expense has been involved in extracting the material and bringing it to light. Much of this material is now available because of mineral exploration and extraction efforts of the 19th and 20th centuries, particularly in the Western United States.

Some of the rocks are quarried, but a large portion of them have simply been left behind in the wake of exploration ventures. Interestingly, in many cases those boulders interlaced with colors and crystals were discarded because processing them to extract their mineral content would have been too difficult and costly.

Now, many years later, these are the specific artifacts that companies like ours are seeking. It’s living proof of the old adage, “One person’s trash is another person’s treasure.”

THE EYE OF THE BEHOLDER

Because these fantastic rocks are more expensive than more ordinary types of natural stone, questions about their overall value in a watershape or landscape naturally arise.

Yes, there are budget issues to be addressed, and because of the weight often involved, the considerations go well past the cost of the stone itself to include the costs of transport and of the structures needed to support them. In many cases, this is why we see use of special stones as highlights or focal points.

This is also why we often see projects in which a mix of natural and artificial rock is used. If a project is particularly large or tall, for instance, faux material reduces the support needed for structural integrity. This is a common strategy in big theme parks: The mountain may be constructed of lightweight material and visitors will never get close enough to scrutinize it. Where visitors get close enough to touch the stone, however, natural rock is commonly used.

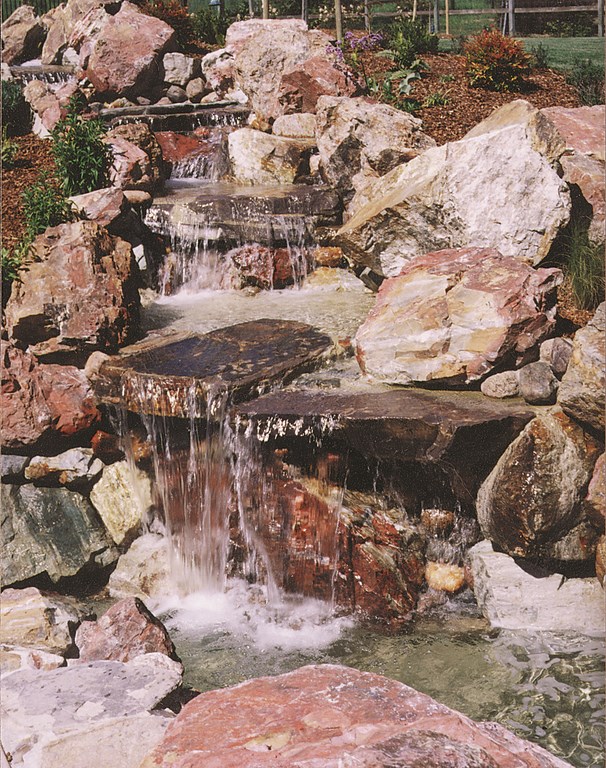

| Figure 1: This project was completed for a modest residence in Northern California. We acted as consultants in selection and placement of the stones and carefully chose some outstanding specimens to mix in with more run-of-the-mill stones. We also made certain the best of the rocks would get wet and show off the shimmering depth and mineral-rich colors. (Photos by Linda Svendsen, Linda Svendson Photography, Concord, Calif.) |

Mixing large and small stones is another option. Where weight isn’t a primary consideration, we’ll often see large specimen boulders, perhaps 20 tons in weight, placed among less expensive, more common material to achieve a dramatic effect.

However they’re used, the relevant issue here is whether or not the use of the more expensive material is justified by the value it adds to the work. To a large extent, that’s a subjective issue, but I’d suggest that what we’re talking about here is the place where geology meets art and that it’s a possibility limited only by the imagination. On those terms, it’s an option that should be introduced to a discriminating clientele as a means of adding something truly special to their projects.

At that level, it’s all about artful use of highly colored and featured boulders and how they can be used to enhance a setting. If the surroundings are right, if the plantings are right, if the design lends itself to natural touches and if the budget has room, the designer or builder who is aware of the possibilities has a distinct advantage.

Now it’s a matter of selecting the right rock and placing it in the most effective, dramatic context – and very often, that context involves water.

AWASH IN AWE

Many of the world’s most enduring design philosophies embrace an interaction of rock and water. Renaissance fountains, Japanese gardens and modern public spaces all feature sublime combinations of water and stone. Whether your work draws directly from these “schools” or is based on your own intuitive use of rock and water, the power of the combination is undeniable.

In one watershape seen here, for example, several different types of rock of various shapes, sizes and colors have been used in the same composition (Figure 1 above), creating a set of visual relationships between the different types of stone and the water itself. There’s a harmony here, and careful placement of the large boulders allows viewers to contemplate the geological story of the rock as they take in the scene.

It’s an unfolding pleasure: The viewer is invited to approach the water by various flat-sided boulders that create bridges and seating areas at water’s edge. In turn, these areas create spaces for intimate viewing as the eye is drawn to large, dramatic boulders strategically placed in view.

| Figure 2: These rocks were installed as part of a grand program for a Northern California estate. In this case, we were able to use more outstanding rocks with a greater palette of colors. The effects here were achieved in coordination with two contractors: Hacienda Pools and Marker Masonry, both based in Pleasanton, Calif. The rocks and boulders were supplied by Morgan’s Masonry Supply (San Ramon, Calif.) and Western Rock & Boulder. |

In design terms, the architect has used the stone to exploit water in three ways: as a dynamic element, falling over the larger boulders; as a passive element, collected in reflecting ponds; and as a soothing element, meandering in a rocky brook. In all of these spaces in the composition, the water leads the eye to explore the rocks that create and/or frame the effects.

It’s also possible to broaden the experience of rocks and watershapes by introducing other design elements to the composition, including lighting and plantings (Figure 2 above). Here, the designer accentuated the featured waterfall with fiberoptic backlighting to create an extraordinary nighttime centerpiece, while landscaping with various types of exotic and indigenous plants has been used to complete the vision, day or night.

The rocks and boulders that surround the watershape don’t dominate the composition. Rather, they serve to highlight the foliage while informing the entire project with a natural feel.

Finding, relocating and placing boulders like these is a special job with special rewards: The right rocks highlight a setting, extend its impact on viewers and weave beautifully into the overall effect created by a watershape or surrounding landscape.

Placed in a greater setting of geological history, the shaping of the earth and the movements of its crust, these rocks and boulders not only are beautiful, but they also become conversation pieces, points of pride and yet another way to build emotional connections between clients and their watershapes.

Rick Bibbero is vice president of business development for Western Rock & Boulder, a Fallon, Nev.-based supplier of decorative and unique rocks and boulders for a worldwide clientele. He came to the firm with more than 25 years experience in real estate development, landscape and watershape design and land use issues in Northern and Central California, most extensively in the environmentally sensitive region around Big Sur. A self-described “rock hound,” part of Bibbero’s job includes finding new sources of unusual rock material, an assignment that often takes him deep into hidden country and the remote back roads of the Western United States.