Nature’s Balance

It’s a tale of two professions: Pool and spa people are taught to keep things dead; pond people are taught to keep things alive. Pool people sell chlorine; pond people sell de-chlorinator. Pool people sterilize; pond people fertilize. This contrast in approaches to basic water maintenance is perhaps the most significant difference between two trades that are coming into closer and closer contact with one another every day.

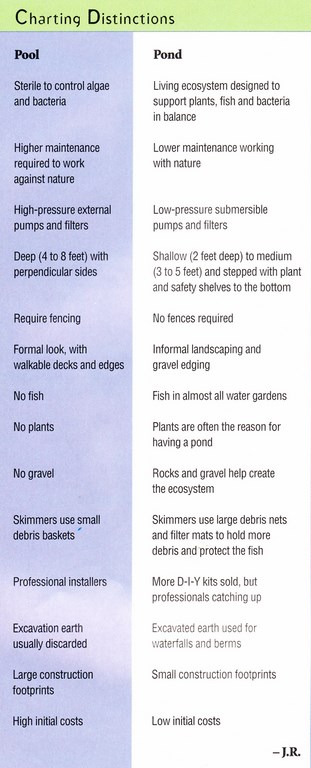

At issue between the two groups is whether to work against nature in a sterile system, or work with it to create an ecosystem. Each discipline has a foundation in the science of water chemistry and both have a place in the world – but beyond that (and as the table below demonstrates), things really couldn’t be much different.

As more and more pool/spa professionals move into water gardening and more and more landscape designers and architects get into pools and spas, there’s an increasing need for all of us to understand these water-treatment distinctions and the basics of each approach. I come from the pond side, so I’ll cover things from that perspective in a pair of articles – a science-oriented overview this time before we get more specific about pond installations next time.

ECOSYSTEM 101

In an “ecosystem approach” to maintaining water quality, almost everything must be kept alive. At the same time, however, the population levels of some organisms must be kept under control and in balance with the other organisms in the system. When the balance exists, the ecosystem thrives.

Finding that balance is, in a nutshell, the fundamental challenge of maintaining a living system.

All of the organisms in a particular ecosystem live within a range of conditions created by their interactions with one another as well as by the overall climate of the region; the microclimate, geology and geography of the specific setting; and the influences of people on the system. None of these factors is static for long, and each influences the balance of the ecosystem.

Striving for balance among these factors requires an understanding that the size of the system has absolutely everything to do with how much life it can support. The smaller the ecosystem, the harder it is to create a balance: The fewer the components there are to work with, the more likely it is for one small thing to tip the scale out of balance.

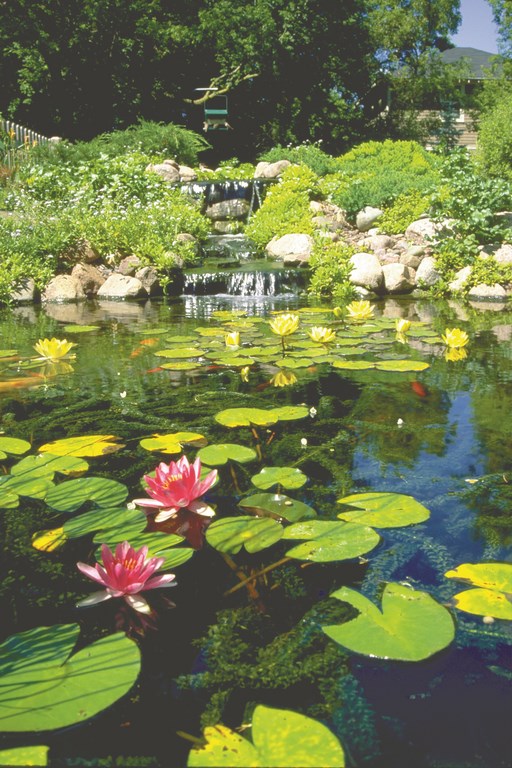

This is why it can be very much harder to strike a balance in a small ecosystem such as a backyard pond than it is to hit the mark in something as big as a man-made lake. The smaller scale narrows the acceptable parameters for each factor and makes it more difficult to design in such a way as to make a suitable environment for plants and fish.

One of the most familiar design principles for pond people is known as “The Bucket Rule”: You can only put two gallons in a two-gallon bucket. In other words, each healthy ecosystem can only hold a specific amount of each component in the system, and failure stalks those who try to take out a component or put in more than two gallons of another component and expect the bucket not to overflow or break. Ultimately, a new and proper balance will establish itself, even if you don’t like the outcome!

To illustrate: Many ecosystem managers have tried removing the predators from an ecosystem to enable the prey animals to thrive. The prey animals will indeed do well for a time, but they will eventually overpopulate the ecosystem and will, in effect, try to cram three gallons into their ecosystem’s two-gallon bucket. Nature soon will reassert itself, and the prey animals will die of starvation, disease or some other catastrophe that will reset the balance.

NATURAL CYCLES

To work with nature rather than against it, it’s important to understand not only that balance exists and will assert itself over time, but also that nature uses cyclical processes to achieve complex sets of balances in which each component is important.

Energy from the sun and energy from the breaking down of chemicals (or digestion of food) is used, for example, to produce growth of plants, animals and microorganisms. Much of this energy is recycled from one organism to the next, and nutrient chemicals are also recycled from one organism to the next through consumption of the previous organism or its waste products.

Energy from the sun and energy from the breaking down of chemicals (or digestion of food) is used, for example, to produce growth of plants, animals and microorganisms. Much of this energy is recycled from one organism to the next, and nutrient chemicals are also recycled from one organism to the next through consumption of the previous organism or its waste products.

Or consider the nitrogen cycle: Nitrogen and hydrogen atoms from the air are transformed into ammonium molecules every time lightning strikes, and these molecules are then washed into the ecosystem with the rain. (The ammonium molecules also can be added to the ecosystem through fertilizers.) Bacteria then break the ammonium down into nitrate.

Plants combine these nitrate molecules with other molecules to produce proteins. Next, animals eat the plants (or other animals that ate the plants) and eventually release waste ammonia molecules. Certain bacteria consume the ammonia and release nitrite molecules into the ecosystem, and other bacteria consume the nitrite and then release nitrate into the ecosystem. This nitrate can be picked back up by plants, or it can be consumed by other bacteria that release nitrogen back into the air, where the process starts again.

This process, by the way, drives the whole planet, not just a pond. And this is just one of the many cycles to be observed and requiring balance in even the smallest of ecosystems.

Indeed, all of the nutrients and minerals are constantly passing from one organism to another in a thriving ecosystem. Oxygen, carbon, iron, copper, phosphorus, hydrogen and all the other basic elements have their own cycles.

Indeed, all of the nutrients and minerals are constantly passing from one organism to another in a thriving ecosystem. Oxygen, carbon, iron, copper, phosphorus, hydrogen and all the other basic elements have their own cycles.

When one part of any cycle is removed, the whole cycle quits working and the consequences may prove deadly. If, for example, there are too many waste molecules of ammonia added to a pond – either because there are too many fish and too much food or because there aren’t enough bacteria to consume the waste – there will be a build-up of ammonia.

Ammonia is toxic to fish at very low levels. All it takes, in fact, is just 40 ammonia molecules per million water molecules to kill fish quickly, and physical stress that often leads to sickness or death begins at concentrations as low as 1 ppm. For its part, nitrite in a pond is toxic at any level that is detectable, while nitrate is quickly toxic at levels above 225 ppm.

(By way of comparison, chlorine is deadly to fish at 0.5 ppm, explaining why a pool or spa maintained with chlorine at 1 to 3 ppm is a big problem where fish are concerned.)

FINDING COMFORT ZONES

While it is certainly true that natural ecosystems operate within narrow ranges for a few of their parameters, it can also be said that most organisms in any healthy ecosystem can tolerate wide fluctuations in some of their chemical and environmental conditions.

A goldfish or water lily, for example, can tolerate a range of temperatures from just above freezing to around 100 degrees Fahrenheit – but add just a bit of chlorine and both are goners. And when several parameters are at the edge of the tolerance range for any organism, it will take less fluctuation in some seemingly unrelated (and usually not very bothersome) parameter to kill them.

|

Tracking Similarities [ ] Both pools and ponds are backyard entertainment and relaxation centers that offer beauty, excitement and fun. [ ] Similar design, creativity and installation skills are required to cope with utilities, permits, safety, fencing, excavation, electrical and plumbing tasks. [ ] Pumps, piping, and filters are used to circulate and clean the water. [ ] Concrete or flexible liners are used to retain the water. [ ] Skimmers are used to collect floating debris and protect the pump. [ ] Both are available in inground and aboveground designs. [ ] Both installations often require or benefit from a waterfall. [ ] Installations for both should blend into the landscape, and they can be simple to install or quite elaborate. [ ] Both require maintenance and related chemicals unique to each product.— J.R. |

The basic concept isn’t complicated: The healthier the ecosystem, the healthier its inhabitants will be, and the healthier an organism is, the greater its ability to fight against a single problem. As simple as that principle seems, however, the complications enter when you consider that the level of a given chemical can vary from ecosystem to ecosystem – and vary when it comes to how much is required by individuals within the ecosystem.

In essence, managing ecosystems is about governing the factors within your control (populations of fish, types and quantities of plants, degrees of aeration and filtration), observing the consequences of your actions and making adjustments as you go. Experience helps when it comes to recognizing what’s happening, but the truth is that these systems can be are tricky – especially if the pond is small.

There is, of course, one factor whose “comfort zone” you intuitively know is more important than most others. Oxygen is 21% of the atmosphere – around 210,000 ppm in the air around us. Good quality water has as much as 13 ppm of free oxygen, so fish already live in an environment low in oxygen and there isn’t much room for lower oxygen levels in a pond. That’s why aeration can be so important.

We could roll on and on through factor after factor, but let’s consider the basic point made: All of these processes are critical to life, and in a pond that means learning to balance the elements within the scale of the system. If you succeed in establishing such balances, then the system will work. If you don’t, nature will do it for you – and odds are you won’t like the results!

It’s also important to note that none of this is to say that life itself is fragile; rather, the delicacy comes in maintaining a balance of life that serves the specific needs of a man-made ecosystem. Fact is, nature is quite persistent, and there are really very few sterile environments on earth where nothing survives – which is why maintaining a sanitized swimming pool environment is so difficult.

THE STERILE SYSTEM

Whenever people try to keep growth of plants or animals to a minimum, they can expect nature to try to fill the voids. Even the culture of a single organism, such as a corn crop, will be infested with insects, diseases, weeds and larger organisms such as crows, raccoons and deer as nature fills the void. The same holds true for a sterilized swimming pool.

At times, it can be tough for people who work to maintain water in a sterile state. After all, water is the growth environment for many life forms, some benign and some deadly to humans. While it is easy to understand the desire to maintain the water in a swimming pool or spa in a crystal clear and sterile state, it is not easy to do – especially outdoors, where algae and bacteria both travel through the air in a spore stage.

At times, it can be tough for people who work to maintain water in a sterile state. After all, water is the growth environment for many life forms, some benign and some deadly to humans. While it is easy to understand the desire to maintain the water in a swimming pool or spa in a crystal clear and sterile state, it is not easy to do – especially outdoors, where algae and bacteria both travel through the air in a spore stage.

To get the job done, aggressive chemicals such as chlorine, bromine, copper compounds, ozone and others must be repeatedly applied to pool water to try to keep up with nature’s attempts at filling the void. Any other kind of sterilizers, including ultraviolet light or even boiling, must be run continuously. No matter what is used to sterilize the water, it is difficult to keep it sterile, and it must be continuously monitored.

Just as control of a sterile system requires an understanding of the chemicals and processes involved, so, too, must the pond keeper have an understanding of the factors that keep and ecosystem alive.

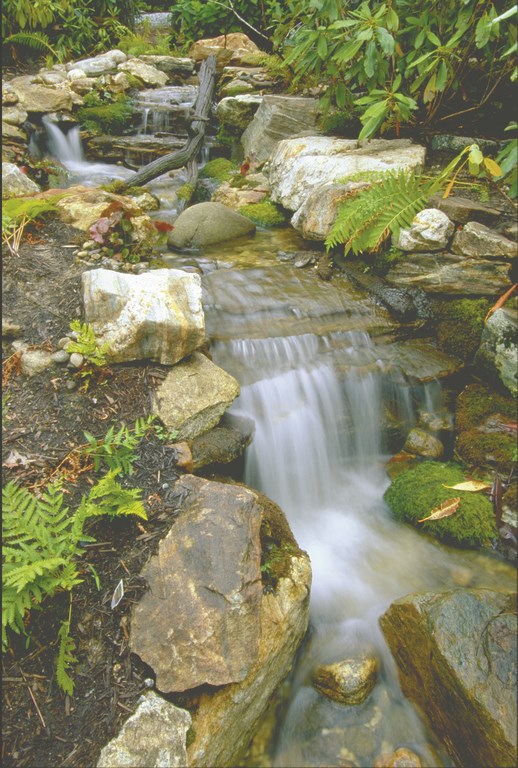

A man-made watershape that mimics nature is still an artificial ecosystem that requires control and understanding. Just as with a pool or spa, a good pond design has to be followed by good installation – and by someone doing the job of keeping the system working. The less work the pond keeper or owner has to do, the more likely it is that he or she will actually do it!

Next: Establishing a largely self-sustaining pond system – one that requires minimal labor on the part of the homeowner or pond keeper and remains beautiful – requires understanding and proper implementation of several key components, including the filter, pond container and circulation system. We’ll cover these components and more in the second part of this article.

Jeff Rugg, ASLA, is a writer, educator and consultant on landscaping and water gardening and an employee of Yorkville, Ill.-based Pond Supplies of America. He holds degrees in science, zoology, horticulture and landscape architecture and uses his many interests to help others learn about nature. Before joining Pond Supplies of America, he managed garden centers in Texas and Illinois and once owned his own water-garden and wild-bird store. His weekly newspaper column, “A Greener View,” is syndicated nationally in as many as 400 newspapers, and his articles and photographs have appeared in Pond Keeper, Water Garden, Landscape Contractor, Ponds USA, American Nurseryman and other publications.